This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

WIFE OF ANTI-RACIST CLERIC IS ATTACKED, I read in the New York Times as I flew home from Los Angeles a few days after Easter. Margaret Railey, the 38-year-old wife of the Reverend Walker Railey of Dallas, was found beaten, choked, and unconscious on the floor of their garage when her husband returned from studying at the library shortly after midnight on April 22, 1987. The police had no leads in the case. “Dr. Railey, who is white, has been an outspoken critic of racial prejudice in this city,” said the Times. According to the executive minister in Railey’s church, Gordon D. Casad, Railey had received a series of threatening letters in the preceding weeks and had preached his Easter sermon wearing a bulletproof vest.

It took a moment for the realization to sink in that this bizarre episode had taken place in my very own church, the First United Methodist Church, on the corner of Ross and Harwood in downtown Dallas. This was the church I grew up in and angrily ran away from and retreated to on several guilty occasions. What I always had hated about my church was its instinctive fear of confronting society, but here was a minister who had spoken out against racial injustice and inequality in a city where such things are rarely said aloud. Here was a man threatened with death in that same sanctuary. And here was a man whose wife was strangled into what the doctors called a persistent vegetative state, for no other obvious reason than that someone wanted to punish Walker Railey for preaching the truth.

Was this Dallas? I asked myself. The open savagery of the Railey tragedy seemed oddly wrong in a city that is deeply preoccupied with appearances. From the beginning there was about the story a vague but haunting discordance.

And yet I was willing to believe that perhaps Dallas had returned to the racial violence of the fifties. Apparently Dallas worried about that too, for the next week the city was on its knees in prayer services and editorial self-reproach. It was a moment when people of various faiths and races stopped to pray for Walker and Peggy Railey and their two young children, Ryan and Megan. “Fight on, Railey family,” cried the Reverend Daryll Coleman of the Kirkwood CME Temple Church in a rare gathering of the races at Thanks-Giving Square. “Fight on, soldiers of righteousness and truth. Thank God for today.” The Baptists issued a statement that “the fact that a minister’s clear stand against racial injustice and bigotry would jeopardize his life is an indicting commentary on our society.” Rabbi Sheldon Zimmerman of Temple Emanu-El concluded that the Railey family had been “singled out because of his almost prophetic stance in regard to injustice in any form.”

As Peggy lay in intensive care, hundreds of visitors came day after day to Presbyterian Hospital to pay homage to a woman few people knew well. The traffic was so great that volunteers from the church came to assist. Peggy’s condition, at first critical, settled into an awful stasis. She was neither dead nor alive—it was as if she were waiting for some momentous resolution before she could either die or be released back into life. And as for her husband, his tragedy seemed unbearable. He had been the rising star of Methodism, as some called him, an electrifying preacher who had awakened the slumbering old church and infused it with his own extraordinary vigor. Now he was crushed by some unknown force too vast and heartless to be fended off by faith alone.

On the Sunday after the attack, the congregation of First Church returned to the sanctuary in a state of shock. There was an obvious show of security police, which added to the air of continuing menace. From the pulpit, Casad read a message from Railey, who remained in the hospital to be near his wife. “I do not know why senseless violence continues to pervade society, nor do I understand why the events of this past week took place,” Railey’s message said. “You have proven to me and all of Dallas that our church is a family. . . . I have been reminded once again that the breath of life is fragile but the fabric of life is eternal.”

Peggy was neither dead nor alive—it was as if she were waiting for some momentous resolution before she could either die or be released back into life.

It is worth pausing to wonder at a city where a crime might assume such metaphorical power. When I was a child in the First Church, our minister, Robert E. Goodrich, Jr., used to speak about the “climate” of the city. It was one of his favorite sermons, one he turned to on that Sunday after John Kennedy came to town and became the 111th homicide of 1963: “There’s no question about a relationship between physical climate and life. How about the spiritual and cultural climate of a neighborhood, a city, a home?”

In this allusive fashion Goodrich would imply that Dallas was not innocent of Kennedy’s murder. There was something about the climate of the city that generated tragedy, that caused lightning to strike. Dallas is a city distinguished by clean, quiet, well-ordered suburbs; it is a pious town, with more than 1,200 churches and the highest-paid preachers in America. Many of the largest Protestant congregations in the world are in the Dallas–Fort Worth area, including seven of the top twenty churches in United Methodism. But all this piety and bustle hides another Dallas. It is number one among large American cities in the rate of overall crime. It has the highest rate of divorce. Dear Abby surveyed her readers last summer and concluded that Dallas–Fort Worth has more unfaithful spouses than any other region. One out of every six murders in Texas occurs in Dallas County. These grim figures describe the climate of the city today. Nevertheless, I felt hope and pride in a city that was painfully examining itself. It seemed to me that it was the special destiny of Dallas to have to grow through tragedy.

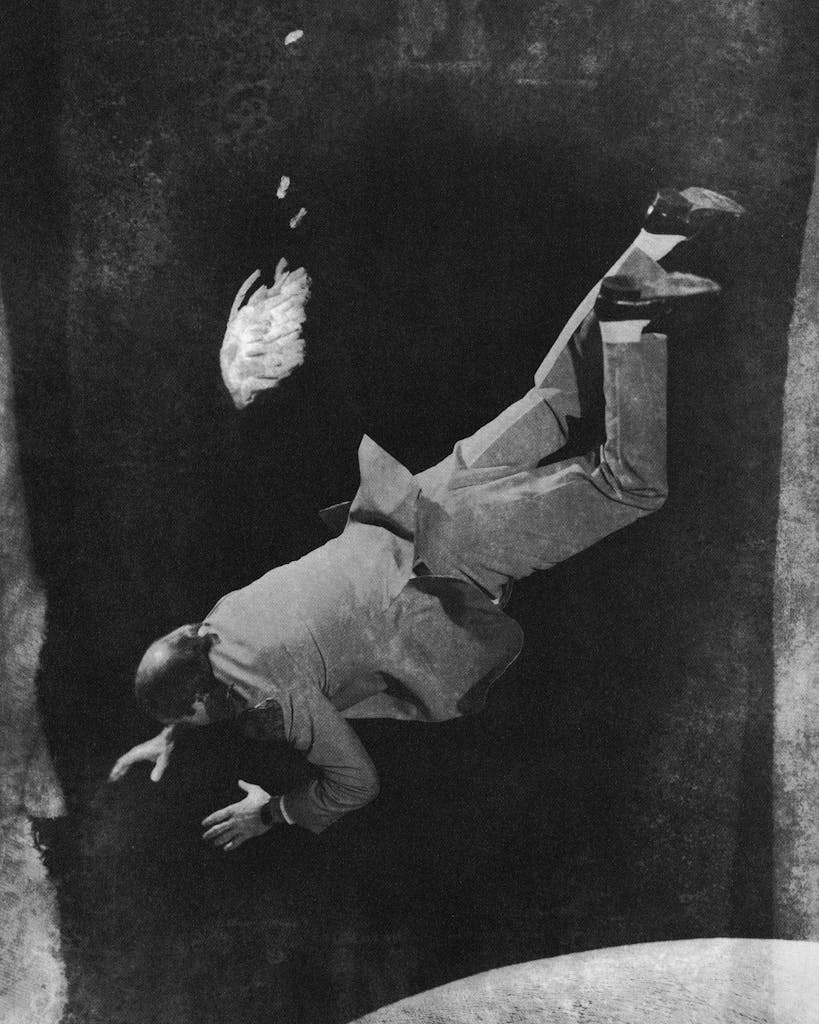

These were my thoughts until nine days after the attack. Then Railey locked himself in his hospital suite and ingested three bottles of tranquilizers and antidepressants, leaving a lengthy suicide note that said “demons” had been inside him for years and he was tired of trying to be good. By the time police broke in the following morning, he too had fallen into a coma. The focus of suspicion shifted from Dallas to Walker Railey himself. Civic introspection abruptly stopped: If Railey were guilty, then Dallas must be innocent. But I wasn’t so sure. It seemed to me that the Railey case went to the essence of Dallas, because it was a case of contrasting appearances. Who was Walker Railey—a holy, martyred minister or a depraved and perhaps insane villain?

Although First Church is not even the largest Methodist church in Dallas, it has a reputation of being the mother church of Methodism. Eight men who stood in this pulpit before Railey went on to become bishops; indeed, Railey’s own election to the episcopacy was regarded as a certainty, perhaps as early as 1988, when he would have become one of the youngest bishops in the history of Methodism. Even his appointment as senior pastor of First Church in 1980 at the age of 33 was an “astonishment,” according to eminent Methodist theologian Albert Outler: “He leapfrogged over two dozen of his elders who thought they were his equal.” For ten years First Church had been losing members, as had many downtown churches all across the country, as had Methodism itself. “He breathed life into this church from his first sermon, when he literally blew into the microphone,” remembers the choir director, John Yarrington, who became Railey’s dear friend. Membership quickly increased, as did the budget, which more than doubled over the seven years that Railey held the pulpit.

New people came to First Church because they adored Walker Railey. “I’ve heard Harry Emerson Fosdick, Ralph Sockman, Ernest Fremont Tittle, and Norman Vincent Peale,” says G. W. French, a lay leader in the church, “and I still feel that Walker Railey was the greatest pulpiteer I ever heard.” For some of the older members, the personality cult they saw evolving around Railey took their breath away. Railey was a vigorous, outspoken advocate of certain social issues endorsed by the yuppie element, which had begun to make up a new, younger core of the congregation. He opposed capital punishment, supported equal rights for women and minorities, declared his ambivalence on the subject of abortion, and defended the rights of homosexuals. He preached an “open letter to President Reagan” calling for increased arms control. All of those stands, in the context of Dallas, seemed rather brave, although it is also true that many Methodist ministers in town had preached similar sermons, and Railey’s social liberalism was pretty much what United Methodism had come to. Personal behavior, that is to say, morality and ethics, was rarely mentioned. Railey often inveighed against the disparity of great wealth and great deprivation that characterized the city, but he himself had grown comfortable with his $100,000 annual salary, his luxurious Lake Highlands home, and the many perks, favors, loans and subsidies that came from being a high-steeple preacher in a wealthy Protestant congregation. For a young man who had grown up in the little western Kentucky farming community of Owensboro, the son of a sheet-metal worker, it had been quite a climb. “To a certain extent he was an existential man,” observes Dallas city councilman Craig Holcomb, one of those who had been drawn to Railey’s ministry. “He worked very hard and created who Walker Railey was going to be.”

Because of the importance of First Church within the denomination, many of the congregation are ordained ministers who are retired or working in other areas of the ministry. Among that group Railey was a polarizing figure. The Reverend Howard Grimes, who taught Christian education at SMU’s Perkins School of Theology for 33 years, calls Railey “one of the greatest, if not the greatest, Protestant preacher in the latter half of the twentieth century. He had become God for a lot of people and maybe me.” The younger clergymen in the congregation—Railey’s contemporaries—tended to look at him with less awe and with more than a little resentment. “His popularity at First Church was such for many people that they lost all sense that he had any imperfection,” says Reverend Spurgeon Dunnam III, the editor of the United Methodist Reporter. Dunnam and Railey had jostled for power in the corporation that is buried inside the denomination. “The politics of the church are so subtle that only the most astute and discerning could understand what was going on. Walker was very analytical and perceptive; he took to that process very early. In the course of numerous different meetings it became clear to me his primary agenda was to be elected to the episcopacy as soon as possible. He campaigned for it by accepting speaking engagements here, there, and everywhere. He seemed incapable of saying no to serving additional outside responsibilities. His ambition was so completely unchecked.”

Within a few years of his arrival at First Church, Railey had become one of the most prominent churchmen in town, rivaling even W. A. Criswell at the immense First Baptist Church a block away. “In the past, whenever something religious would come up, the press would ask Dr. Criswell what he thought of it. Pretty soon they stopped that and started asking Walker Railey,” says the Reverend John Holbert, who taught Railey Hebrew at SMU and who sings in the choir at First Church. Railey served as president of the Greater Dallas Community of Churches. He was on the United Methodists National Board of Global Ministries. He was selected to preach Protestant Hour sermons on a nationwide Christian radio network. Already his name was widely known among Methodists as a man destined not just for the bishop’s chair but for something more—for greatness, in whatever form that might assume.

And yet there were extraordinary pressures that were at work and were already evident in Railey’s personality. Several times he told Gordon Casad that the congregation at First Church “could never forgive even one bad sermon,” so he slaved over his lessons, polished his delivery, choreographed his gestures, until each one of them was a characteristic Railey gem. Once, in the receiving line after the eleven o’clock service, a seminary student asked what it took to preach a sermon like the one he had just heard, and Railey answered candidly, “About thirty-five hours.”

In a church with a congregation of nearly six thousand members and a $2 million budget, a pastor spends a considerable amount of time visiting hospitals, preaching funerals, counseling troubled youngsters, running administrative meetings, setting budget goals—it’s a demanding occupation. Railey had a staff of 65 people to assist him, but just keeping the staff appeased was a full-time job. “He was the kind of preacher who knew everybody’s name,” says Diane Yarrington, John Yarrington’s wife and Peggy Railey’s closest friend. “He wrote hundreds of personal notes to people all the time—on your birthday you’d always get a handwritten note from Walker. He would make a special trip to a high school to see a play that one of the Sunday school children might be in. He spent hours and hours a day doing that kind of thing. And of course it wore him down.”

Railey found in the church the loving family he himself had never known as the child of alcoholic and often neglectful parents. John Yarrington became “the older brother I never had.” Howard Grimes was “a real father to me.” Mrs. Knox Oaxley was “my Dallas mother.” It was typical of Railey to seek out such ersatz family members. He wanted to be loved and esteemed; he also wanted to return to his congregation the steady, attentive care he had craved as a young boy. By pouring that kind of love on the thousands before him, it was as if he were ministering to the angry and neglected child inside himself. He would not let them down, as he had been let down. When, in times of grief or trouble, a parishioner would stumble or his faith would fail, Reverend Railey was there—strong, certain, and unwavering. His faith was a compass point by which others in the church could steer their fragile beliefs. In these ways Walker Railey became something larger than himself and, subtly, something other than himself.

Because behind the public face of this caring, highly blessed young man, with his beautiful wife, his charming children, his prestigious job, his important future, there was another Walker Railey. This was a man so besieged by the doubts and worries he held aside during the day that he seldom enjoyed an untroubled night’s sleep. This was a person seen only occasionally by people close to him—his staff, for instance, who idolized him and were sometimes crushed by a volcanic temper that slept and slept then suddenly savagely erupted, usually over some small point such as the lighting in the sanctuary or the presentation of the budget. Nor were these eruptions followed by periods of remorse, which would have made them easy to forgive; instead, a certain cool satisfaction took hold of him. He would not call back the rain of shattering insults that led to tears or angry resignations. In the recent past when this other defiant, uncaring, self-centered Walker Railey had gained ascendancy, friends had talked him into seeing a psychiatrist, to help him “cope with stress.” Lately, however, when many of those closest to him had suggested that he go back to the psychiatrist, that he slow down, that he take a sabbatical, he had coldly cut them off.

When word of another Railey outburst circulated among the congregation, it was usually seen as more evidence of his temperamental genius. How insidious that must have seemed to him! Whatever fault he confessed to, whatever awful behavior he committed, only brought him new credit. Or perhaps—and this is the worst thing that can happen to a preacher, it is where he crosses the line between serving the forces of good and serving those of evil—perhaps he had begun to believe in his own perfection. Some of the other ministers in the congregation suspected that Railey had become one of those preachers who see themselves as God’s special messengers, one of those who “become so convinced that they are so holy that they are above the standards they have to preach,” as Spurgeon Dunnam observes. “The sin is to become as God, as one who would take God’s place. Anytime a human being reaches that level he sets himself up for a fall.”

On Easter Sunday, three days before the attack on Peggy, Walker Railey preached what would be his last sermon. In the days to come, it would be reinterpreted in ways that no one in the congregation that morning could have imagined. On this holy day, which is set aside for hope, love, and rejoicing, the cast of characters who would figure in the tragedy were all in place in the sanctuary, about to begin a weird and—one could believe—demonic journey into a world of passion, violence, and madness. Just before the eleven o’clock service, the seventh of a series of threatening letters addressed to Railey was slipped under Gordon Casad’s office door. “EASTER IS WHEN CHRIST AROSE, BUT YOU ARE GOING DOWN,” the note said. There was already a police guard in the church, but the possibility that the author of those threats had walked unnoticed into the church offices left the staff and the police unnerved. They were even more surprised when an associate pastor, acting on a hunch, ran upstairs and typed out the same message on an IBM Selectric on the third floor. The type face appeared to be the same. Whoever was sending the notes was probably a member of the congregation—perhaps even a member of the staff.

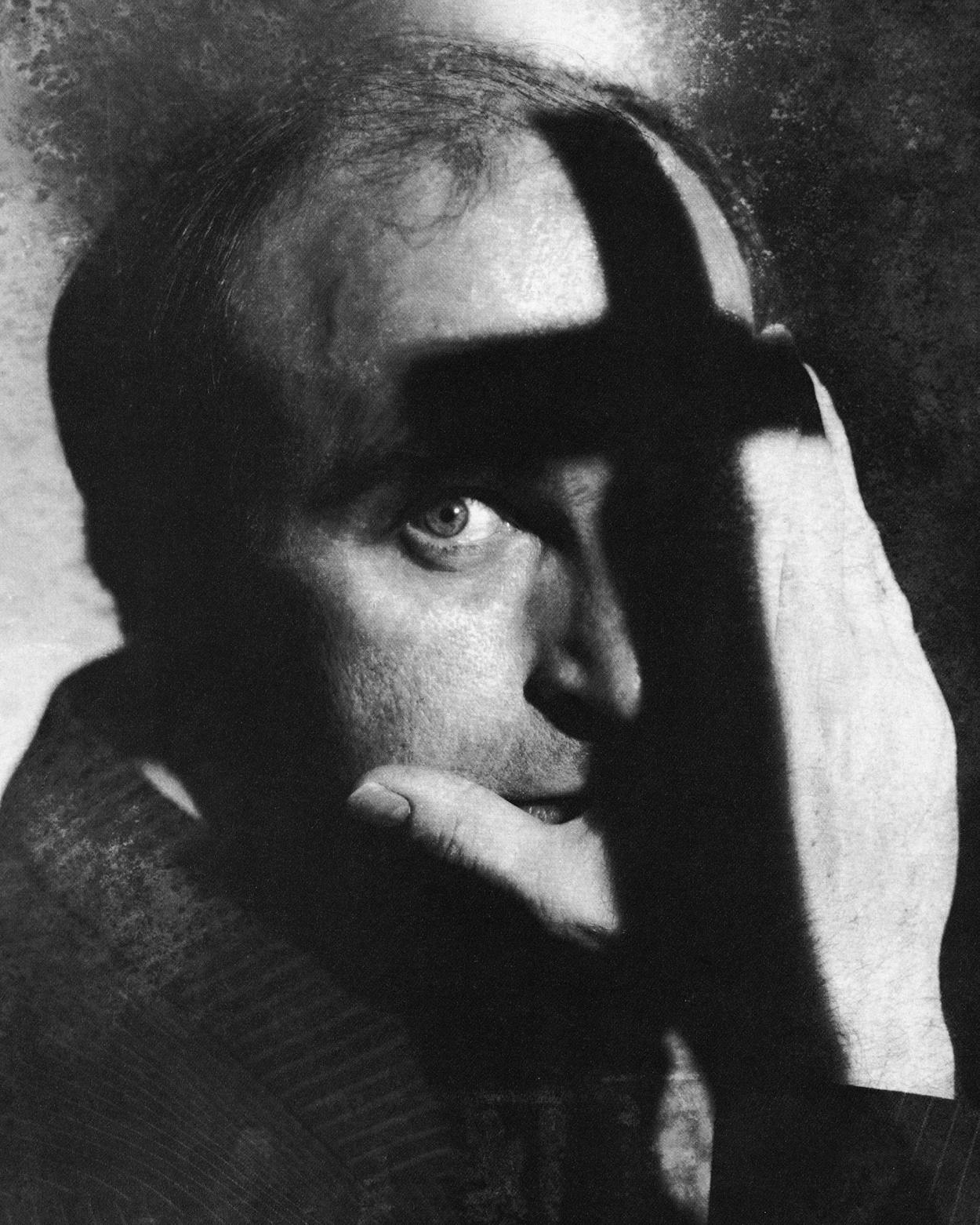

Railey, a medium-size, balding man with intense blue eyes, was pale and thin-lipped but apparently determined to preach. He borrowed an ill-fitting bullet-proof vest from a woman police officer and strapped it on like a corset beneath his Easter vestments.

Few people in the congregation knew about the threats, but most sensed that something was wrong as soon as they entered the sanctuary. Councilman Holcomb noticed that Railey did not enter the procession behind the choir as he usually did. Instead, the choir came in alone, and the pastoral staff entered through a side door—without Railey. “I kept noticing these men standing beside the doors,” Holcomb recalls. “I kept thinking I knew these men, but they’re not from the church.” Later he recognized Investigator Steve Torres as one of the officers who guard the city council. The congregation rose to sing the doxology, and when they sat down Railey abruptly appeared in the pulpit.

Looking out from the pulpit, he saw three thousand parishioners in their Easter finery, filling the sanctuary and spilling out into the hallway, where uniformed policemen had just arrived to guard the exits. It was no longer the predominantly elderly congregation that had greeted him on his first sermon in this pulpit seven years before. Who could deny that Walker Railey had put his stamp on this church and invigorated it with the force of his personality? And yet hovering over the sanctuary was a ghost that haunted Railey and would never let him feel entirely at home here; it was the ghost of Robert Goodrich. All the things Railey wanted, all the honors he sought, Goodrich had achieved. Goodrich had been elected bishop in 1972 and was succeeded in the First Church pulpit by Ben Oliphint, who also became a bishop eight years later. It was Goodrich with whom Railey was compared, however, and not always favorably. “In many ways I’ll always consider that piece of wood up in front of the sanctuary as Bob Goodrich’s pulpit,” Railey would admit. Perhaps it was an act of charity or perhaps it was cleverness on Railey’s part that he brought Bishop Goodrich back to Dallas in his final years of life, when he was ill and doddering, and placed him once again on the staff of his old church, where everyone could compare the old frail man with his lively young successor.

In the congregation on Easter morning was Bishop Goodrich’s elegant widow, Thelma. I should note that she and her husband were close friends of my parents and that she is a woman whose dignity I have always admired. Thelma was sitting with Lucy, the second of her four children. Despite the mascara and frosted hair, one look at Lucy and you could see she was Bob Goodrich’s daughter. She had that knotted Goodrich chin, his thin, drawn smile, and the dark eyes that were his most distinctive feature—eyes that seemed remote but also searching and intelligent. It was a strong face, like her father’s, and if in some lights it appeared hard, in others you could detect a vulnerable and even wounded soul who had lived past the point where life surprised her. When she was younger, Lucy played the piano in the Sunday school class that my father taught. Now Lucy was 45, with two teenage children, but she was still slim and youthful, with the athletic carriage that was also a Goodrich legacy. She had been through two marriages before going off to California and becoming a clinical psychologist. She had come home to Dallas to set up a practice specializing in eating disorders. Along the way she acquired a new last name, one of her own invention: “Papillon,” which means “butterfly” in French. Dr. Papillon once explained “the metaphor of the butterfly” to Reverend Railey when he interviewed her on Faith Focus, his weekly television show: “The caterpillar’s crawling around, feels like the world’s okay, but if they really want to fly, they’ve got to go through the darkest thing they’ve ever seen, which is the cocoon.” According to the local press, soon after Lucy Papillon returned to Dallas, she became Walker Railey’s mistress.

Mrs. Walker Railey sat in a pew halfway back, next to a woman police officer who happened to be a member of the church. It had become unusual to see Peggy in the congregation. Over the last year she had withdrawn from the choir and the children’s Sunday school class that she taught, then from the board suppers and picnics and retreats, and finally from the main Sunday service. Walker explained her absence as illness or a need to be closer to five-year-old Ryan and two-year-old Megan. Although it was true that Peggy had suffered a bout of walking pneumonia earlier in 1987, she had recovered from that; and as for the children, other mothers in the congregation wondered why she couldn’t leave them in the nursery, as they did. Peggy, however, always had seemed a remote personality—as introverted, friends said, as Walker was extroverted—so her retreat from church society was only partly noticed. “She was certainly much less visible than any other pastor’s wife I’ve ever seen,” says a member of the pastoral staff.

Later, while she lay in the hospital, fighting for the marginal edge of life that had been left her, people would describe Peggy as cool and distant, but to those few who she had allowed to know her well, she was a warm and devoted friend. The pictures that would appear in the newspaper did her no justice, because Peggy Railey was quite a beautiful woman. Where Lucy was strong and stylish, Peggy was frail and demure, but with a natural attractiveness much like a fresh-faced milkmaid of her native Wisconsin. Peggy had a lovely singing voice—she was second soprano—although her true talents were in her fingers. She had studied organ at SMU, obtaining a master’s degree, and she might have pursued a career as a professional musician if she hadn’t chosen to give herself over to the humbler role of being a minister’s wife. In March, after she had recovered from her illness, she succumbed to friends’ urgings and gave a small lunchtime harpsichord recital at the church, with John Yarrington joining her at the end of the program to sing a Bach cantata. She appeared wan and there was a new hollowness about her cheeks, but in many respects she had never been more lovely. And yet what was most striking about this performance was Peggy’s trancelike behavior; she played robotically, and when the audience applauded her, she gave a sudden startled smile. Where was she? She seemed to be in some faraway sad place. Later people would remember that performance and wonder if Peggy had known about Lucy.

Another of Peggy’s talents was sewing. She had made many of the elegant seasonal stoles that the ministers wore over their robes—Walker was wearing one now, a white stole with the Greek letters alpha and omega appliquéd on either side. Beneath the stole was Walker’s black robe, and under the robe was his suit jacket, and under the jacket was the bullet-proof vest, so as Walker stood in the pulpit his first action was to mop his bulbous forehead with a handkerchief.

He began his sermon with a discussion of a book written in 1965 called The Passover Plot. The premise of the book was that the Crucifixion had been faked. Of course Railey went on to dismiss The Passover Plot—“If there’s ever a day you have nothing of substance to do, and you want nothing of substance to read, it would be a fine book to peruse.” Perhaps he was only using the book as a provocative introduction to the standard Easter rejoicing; the questions that he was posing about Jesus, however, were exactly the same ones that would later be asked of him. Was he truly a martyr—the man who was now standing in Bob Goodrich’s pulpit in a bulletproof vest, the man whose life for the next two weeks would be a march of catastrophe, from the attack on Peggy, followed by Walker’s evasive testimony to the police, and culminating in his attempted suicide? Or was he orchestrating his own martyrdom, creating a myth of himself that would raise him higher and make the drama of his own small life into something grander, something divine?

One could scarcely call me an objective reporter. From the moment I got into the story, I had trouble holding onto my neutrality. I bullied my way into an interview with Railey’s bishop, who said I was “beneath contempt.” I told preachers who refused to speak to me about the case that they were sanctimonious hypocrites. I excoriated the staff of First Church for not confronting the evil that had taken place in their own sanctuary. My behavior was hard to excuse and hard to explain.

In part it was anger at Dallas, a city were pious public faces often hid secret dirty appetites. But Dallas was an old war of mine, one that I had grown tired of fighting, to the point that I had subsided into an exhausted peace on the matter. The truth was that like any old contestant I had begun to sentimentalize the battles of my youth and had become grateful to Dallas for helping me learn who I am.

More than Dallas, there was Methodism. I have seen friends struggle to throw off the narrow-minded strictures of Southern Baptism or the ritualistic magic of Catholicism or the tribal creeds of Judaism. I have encountered religion in extreme forms, from Hare Krishnas and Amish farmers to snake-handling charismatics. And yet, with all my ambivalence about religion, what I feel about people who believe or disbelieve such stringent doctrines is a low-grade envy, for at least a hard-shell Baptist has the literalism of the Bible to react against, a Catholic has the pomp and mystery of the liturgy, and so on, but a Methodist struggles in a fog, not really knowing what is to be believed or disbelieved but learning in a subliminal way what is to be avoided.

I could not fairly hold Methodism responsible for the values of this city, because despite the fact that Dallas is a stronghold of United Methodism, only 7 percent of the population belongs to the denomination, a figure that represents less than half the number of Southern Baptists and is even behind the Catholics. This fact doesn’t alter my opinion that Methodism is the state religion of corporate America, of which Dallas is the purest and most fervent example. Methodism began in the slums of eighteenth-century London and the British coalfields, where John Wesley began his ministry to the underclass. It settled the American frontier in the form of the lonely, tireless circuit rider. And thus it took root in an ambitious, desperately poor frontier people, and it grew with them as their cities grew, as their generations prospered, and as their politics and values changed. So had the church grown and prospered and changed, becoming essentially the same institution its founder had rebelled against.

Yes, I was angry at Methodism because I thought it had turned into Nothingism and was only in business to stay in business. My particular quarrel with Methodism began here in First Church, however, where for so much of my adolescence I had felt confused and bewildered and overlooked. It had seemed to me then that the special quality of my church was to float above the real world of lust and violence, passion and broken hearts, in a higher atmosphere of untroubled Christian behavior. Human failings were seldom addressed. I recall when the assistant pastor left his family and ran off to Colorado with a ski instructor. His name was never mentioned again. All that remained of him was some intoxicating vapor of sin and forbidden desire—an intimation of another world I was not supposed to know about. The church was like a timid old woman hiding behind shutters, shielding herself from confusion.

I had seen Walker Railey preach on Christmas Eve, 1984, when I was back in Dallas to see my parents. It was a tormented moment for me, a time when I had been confounded by my own behavior and eager to seek forgiveness. In that raw condition I experienced what so many would later speak of: the sensation that Railey was preaching to me, that those large and expressive blue eyes that swept across the sanctuary like a searchlight were looking for me.

Now, after the attack on Peggy Railey, I had come back inside the old sanctuary, had listened to another sermon that refused to acknowledge what had happened within the church’s own family. Week after week had passed with one revelation after another and only the most oblique references from the pulpit about what was transpiring in the world beyond the stained glass windows. Nothing was said of Railey’s attempted suicide. Nothing was said of the sensational revelations of Lucy Papillon’s grand jury testimony, in which she talked about their affair, which had gone on for more than a year, their marriage plans, and their assignations “while he was out preaching”—they had even arranged to meet in England when Railey returned from a World Methodist Council meeting in Nairobi. Nothing was said of Railey’s refusal to cooperate with the police or his decision to plead the Fifth Amendment before the grand jury. The church was in a state of delirium (“We’re fine, the church is fine, everything’s going to be fine,” a member of the board assured me). I fought an impulse to stand up and shout Walker Railey’s name out loud.

On the night of April 21, 1987, at 6:30 in the evening, Railey drove into the family garage. He says he found his wife working on a garage door latch with a bar of soap. The spring on the latch had been sticking, and Peggy was trying to lubricate it. According to Railey, he sat on the hood of Peggy’s Chrysler for a few minutes, talking to his wife. She and the children already had eaten dinner, and Walker wasn’t hungry, so the two of them shared a glass of wine. He then left, still in his business suit—ostensibly to spend the evening at the SMU libraries to write footnotes for his book on preaching.

At 6:38 Railey called the time from his car phone. Everyone knew that Railey did not wear a watch; he had given it up when he came to First Church, partially because of his habit of wearing French cuffs, which frayed when he kept pushing up his sleeve to check the time. The phone had just been installed that day, at church expense. It was another of the many security measures the church provided him, including a home alarm system and a separate private telephone line. Railey says he spent the next thirty minutes at Bridwell Library at the theology school, searching for a biography of Anne Sullivan, Helen Keller’s teacher. At 7:26 he was back in his car, calling Janet Marshall, a family friend who was going to baby-sit for the Railey children while Walker and Peggy went to San Antonio for the weekend. At 7:32 he called Lucy Papillon, then drove to her house, where he stayed for about forty minutes. He says he went there to get some relaxation tapes to help relieve his stress.

A librarian at Bridwell remembers seeing Railey sometime after eight, when the minister asked what time the library closed. At 8:30 Railey called Peggy from a pay phone, and she told him she was putting the children to bed. After that Peggy talked to her parents in Tyler until 9:14. Meanwhile, Railey had left the library. He purchased gas at a Texaco station on Greenville Avenue at 8:53 and also bought a wine cooler, which he says accounts for the fact that police would later report him as intoxicated when they came to his house four hours later.

At 9:30 a jogger saw a man in a business suit running through a yard two streets away from the Raileys’ house. Between 10:15 and 10:30 a neighbor heard rustling noises in the alley behind the Raileys’ house.

Railey says he had gone to the Texaco station because he was thirsty and had returned to his research in the main library. The police say they have indisputable evidence that he was lying about his whereabouts from the time he left the Texaco station until a librarian saw him sometime between 11 and midnight. At midnight Railey attempted to give his business card to a Nigerian student at the checkout desk. On the back of the card was a message to the research librarian, asking for help in finding the Sullivan biography. He had also written the time, which was noted to be 10:30.

After leaving the library Railey phoned his home from his car, but this time he called the listed line, which was connected to an answering machine and did not even ring in the house. “I don’t have my watch on,” said the man who never wore one, “but it’s about ten-thirty or ten-forty-five.” Telephone company records show that the call was actually made at three minutes after midnight. “If you want to, go ahead and lock the garage door, and I’ll park out front.” At 12:29 he called his answering machine again, giving the correct time and saying he was on his way home. The theory of Railey’s guilt presumes that Peggy was strangled sometime around 10:30 and that the calls were meant to establish both an alibi for himself and a reason for Peggy to go to the garage.

Eleven minutes after the second call Railey drove into the driveway and found the garage door partly open. The garage was dark; mysteriously, the bulbs had been removed from the overhead light of the automatic door opener. Railey said he left his headlights on and got out of the car. He found Peggy lying behind her Chrysler, writhing in convulsions. Her face was hugely swollen and discolored, yet her hair was scarcely mussed and her glasses were in place. At 12:43 a police dispatcher received a call from Railey, who said, “Uh, I just came into the house, and my wife is in the garage. . . . Somebody has done something to her.” The dispatcher inquired, “Has she been beat up or what?” “I don’t know,” Railey replied. “She’s foaming at the mouth or something.”

“The phone rang about twelve forty-five,” says Diane Yarrington. “It was Walker. He said, ‘Diane, something awful has happened to Peggy. Come quick, come right now.’ We literally raced over there. By the time we got there, the ambulance had arrived. Walker was inside holding Megan. Ryan was sort of sitting on the couch. I talked with Walker briefly, and then I said, ‘I’ll take the children,’ and I asked the kids what they wanted to take with them. They each grabbed a pillow and a stuffed animal. Walker said, ‘Don’t leave me.’ And John said, ‘I’ll be here. I’m like your second skin.’ ”

John Yarrington accompanied Walker to the hospital, and after he had gotten his friend settled, he went to speak to the doctors. “I did not know what had happened. I knew she had been hurt, but I didn’t know how,” he says. “At that point the doctors’ assessment was that Peggy’s neck had been broken. And I asked how would that happen? ‘Well, she was strangled.’ That was the first I knew.”

John went into the emergency room where Peggy lay. “It’s a terrible thing to see; it’s Technicolor in my brain. I’ll never forget her lying on that table, with that blotchy color, a terrible color, a terrible thing to see on someone you love.”

For most of the seven years the Yarringtons had known the Raileys, they had been the closest of friends. Diane and Peggy were like sisters. They spoke several times a day on the phone and sat next to each other in the choir. Peggy accompanied John’s rehearsals every Sunday night. Walker had been John’s boss and also his spiritual guide and soul mate. Several months before the attack on Peggy, the couples had pledged that if anything were to happen—if one of the couples were to die in a plane accident or some other tragedy would befall them—then the other couple would take care of their children. John had made the pledge in all sincerity, but who could believe that so suddenly and so grotesquely it would come due?

The next day Railey went to the police station with a lawyer friend to talk to investigative officer Rick Silva. It is the only time Railey has talked to the police. His story then was that he had come home, spoken briefly to Peggy while she was working on the garage door latch, then spent the rest of the evening in the libraries. He said he had no idea who might want to harm her, except for the author of the anonymous letters. Silva indicated that he would like to set up a polygraph examination, and Railey said he would be happy to cooperate.

During the next week the police learned about the telephone call to Lucy, they listened to the tape on Railey’s answering machine, they discovered a credit card slip from the Texaco station, and they examined the garage door, which seemed to work fine. They found no evidence that the latch had been lubricated; in fact, they learned that the Raileys had complained to the manufacturer and had had a new automatic door opener installed only a few days earlier.

In the meantime Railey stayed in his hospital suite, meeting friends and going through the mail. Lucy came to visit him, carrying a single red rose. One day he received telegrams from both Jesse Jackson and Billy Graham, and he went in to tell Peggy she had made “ecclesiastical history.” She looked at him with open, unseeing eyes. Her brain was damaged but not dead. What she comprehended no one could even guess. Friends played videos of her harpsichord concert and papered her room with pictures drawn by Ryan and Megan. There was some hope, in those early days, that something inside Peggy would stir to life.

“Peggy, it’s Diane.” Peggy’s face was still puffy and discolored the first morning Diane Yarrington got to see her. “The children are with me. It’s just fine. It’s all right.” A tear rolled out of Peggy’s eye. Later others would see her crying—Walker did, even Detective Silva—and they would wonder what she knew or felt. The truth was locked inside Peggy and could never be expressed, but that did not mean that it couldn’t be experienced. What an unendurable tragedy that would be, to be alone with the truth.

The inconsistencies and omissions in Railey’s story had accumulated to the point that Silva telephoned the hospital and told the officers guarding Railey’s room that he wanted to question Railey. When they went to his room they found the door locked. They broke in and found Railey’s unconscious body and his suicide note.

Once again John Yarrington would be standing in the same emergency room, this time over Walker’s body as doctors pumped the drugs out of his stomach. Fortunately, Walker had not taken all the pills that were on his bedside table. Like Peggy, he had fallen onto that ledge of deep unconsciousness between life and death. Unlike her, he had not suffered a loss of oxygen and glucose to the brain, which doctors said probably would prevent her from recovering. She was wrapped in a cocoon from which few ever emerge.

For the next five days Walker lay in intensive care in a room opposite Peggy’s. “It was bizarre and weird,” says John. “You would go to your left to see Walker and go to your right to see Peggy. They essentially looked much the same.” On the Wednesday after the Friday he had attempted suicide, Railey awakened, and the first thing he remembers is seeing his friend standing vigil at his bedside. He had absolutely no recall of anything. It was two more days before he fully resurfaced. Railey asked John then whether he could regain the pulpit. John was startled by the question. “I think it’s very iffy,” he said. Walker seemed surprised and wanted to know why. “Well, number one, you tried to commit suicide. And number two, a lot of people think you strangled Peggy.”

The police had enough evidence to disbelieve Walker Railey but not enough to charge him. After he got out of the hospital, Railey checked into Timberlawn Psychiatric Center while his attorney, Doug Mulder, arranged for him to take a privately administered polygraph. The test indicated that Railey did not attack his wife and did not know who did. The next day at the police department Railey took a polygraph which proved inconclusive, although Railey “showed deception” about the threatening letters. Mulder and Railey arranged for a third polygraph, the results of which they have never made public. Norm Kinne, the frustrated chief criminal prosecutor in the district attorney’s office, convened a grand jury investigation and warned Railey in front of television cameras to either “come before the grand jury” or “leave the country”—an odd injunction to be directed at the main suspect in the case. Railey appeared and took the Fifth Amendment 43 times. No indictments were handed down, but so much of the testimony was leaked to the press that it appeared that the grand jury was called for no other purpose than a public shaming of Walker Railey.

With the justice system at an impasse, a group of Methodist clergymen wrote a letter to Bishop John Russell, asking for a church inquiry into Railey’s relationship with Lucy. The bishop began a lengthy private negotiation with Railey. On September 2 Railey surrendered his credentials, which voided the church’s jurisdiction over him. That meant there would be no embarrassing church trial, but it also meant that Peggy’s insurance would lapse after twelve months. In October Railey signed over guardianship of Peggy to her parents, who had placed Peggy in a Tyler nursing home. Peggy’s father says that Railey has visited his wife “three or four times—that’s about it.” The Railey children continue to live with the Yarringtons.

I knew I was going to meet with Walker Railey because periodically he emerged from seclusion to proclaim his innocence to reporters and give his own version of the tragic events. The meetings were highly circumscribed, and when Railey finally answered one of my messages, I agreed to the same conditions: We would not talk about the case, and we would not talk about Lucy. “Are you a coffee drinker?” Railey asked cheerfully on the phone. He said he would have a pot waiting for me when we met in the morning in his Lake Highlands home.

There was no For Sale sign in front of the white brick house on Trail Hill Drive, although the house was on the market for $279,000. The sole business that was keeping Walker Railey in Dallas was the need to dispose of his property. He had gone through the police, the grand jury, the bishop, and the local reporters, and there remained only me.

Railey opened the door and greeted me. The house was comfortable and spacious, with the sun glinting off the pool in the back yard and making wrinkled shadows on the living room ceiling. Perhaps it was simply the absence of family detritus—toys and books and newspapers—that made the house seem so impersonal. Outside it was warm, but the house was unaccountably chilly—“like a mausoleum,” as Railey observed while we sat at his kitchen table, drinking coffee.

He had been monitoring my presence ever since I had arrived in Dallas two weeks before. “I know that you have a couple of layers of subjectivity that are influencing your writing of this story, one having to do with your opinions about me and one having to do with your inner quarrels with the institutional church,” he told me, quite accurately. I realized that we had been stalking each other with a growing sense of recognition and mission. His mission, old and by now habitual, was to get me to believe in the church—and in himself. Mine was to tear away the many veils of falsity and hypocrisy and get to the truth, whatever that was.

He already knew who I was. But did anyone, even Walker Railey, know who he was? “I get depressed,” he admitted. “I see my psychiatrist twice a week and have been doing that since May, and he helps me look inside myself.” He spends his days now reading the Psalms, playing golf occasionally, “trying to let my soul and my body get together.” A few days before, he had enjoyed “kind of a joyous highlight” because he had played golf with former district attorney Henry Wade. “It was a fun time. And I thought he showed personal sensitivity to me.” Railey said he was worried about the future, about his prospects for a job. “For the first time in my life, at forty, I have no earthly idea what, where, when, how, or anything else. So there’s an element of fear.”

He spoke of his ambition. “Most of the reports have written that I was drooling on my tie waiting to become a bishop, but that’s not entirely true.” Bishops are elected for life, he pointed out, and “you can only bless the opening of Sunday school units so many times until you get tired.” His secret ambition was to stay at First Church another decade, then take early retirement and go to law school, so he could set up a practice in South Dallas to defend underprivileged minorities. I regarded that statement as gratuitous and unlikely; on the other hand, I never did understand the appeal of being a bishop.

“I had three books coming out in ’88,” Railey was boasting. “I was speaking all over the nation. I had been the Protestant Hour preacher—I’d just finished taping the sermons.” Under Railey’s tenure First Church had become “one of the real turnaround stories in the nation.” Everything that he had been working for was coming to fruition. “So you know, I was beginning to feel that my future was okay, but I was trying to get out of the future and more into the present—maybe for the first time in my life.”

“And now, all that’s lost to you,” I observed. “You’ve resigned from the church, the books have been put on hold, your family has broken apart, and your future is in serious question. You’re a man who’s suffered tremendous losses. Why do you think this has happened to you?”

This question had been given to me by psychologists I had consulted, on the premise that Railey might be insane. If he is, he has done enough psychological consultation of his own to dodge the paranoiac response. “I’ve always tried to avoid asking ‘why’ questions because I don’t think ‘why’ questions get you anywhere,” he said, giving me his most defiantly honest stare. “If I’m asking any question, it’s how I can feel the presence of God’s healing power in my life right now, when, for the first time in my life, I can’t even tell you where I’ll be tomorrow.”

He began to recount the events of Tuesday, April 21, leading up to the discovery of his wife’s attack. “I went to the library and started at Bridwell down on the south part of the campus.” He was checking footnotes for his book of sermons. When he finished there, he “walked up to Fondren,” the main library. “On the way to Fondren I stopped by Lucy’s house”—which is directly behind the campus—“for about forty minutes and back to Fondren after getting a Coke at a Texaco station and filling up the car. Worked at Fondren until a little after midnight, about twelve-fifteen or so, I called Peggy to let her know that I was on the way. And I got home about twelve-thirty. I came into the garage and found her.”

Until that point he had told the story in a rapid, shorthand manner—so fast that I completely missed the contradiction between his “walking” to Fondren and filling up his car with gas. He had said he would not talk about the case, and obviously he wanted to skate past this portion. I thought to myself: Here’s a man who has avoided the police and the grand jury. I can’t let him get by me that easily.

“The police said you had been drinking that night.”

“Peggy and I had a glass of wine,” he said.

“At what time?”

“Quarter of seven. And I had a wine cooler when I stopped at the Texaco.”

“I thought you said you had a Coke at the Texaco.”

“I said ‘Coke’ but that was just a Coke break, a coffee break,” he replied. “I went up there to get something to drink. I refer to that as ‘getting a Coke.’ ”

He would not be trapped. He started to talk again about finding Peggy. “Come here, I want to show you,” he said, with a certain demanding eagerness. “I want you to see.” We walked into the garage, which was large and empty of cars. Against the back wall were several storage closets. “I want you to understand that there’s a freezer, there’s a refrigerator, and there are toys that the children use, like the tricycle,” Railey said, pointing out the clutter of an ordinary suburban family, which lined the side of the garage. “In the evening it was not uncommon—six, seven or eight times a night—for one of us to come out here.” He showed me the latch he said Peggy was working on early in the evening of her attack. Somehow it had gotten bent. “How it got bent, I don’t know.” Railey’s voice, even though it was nearly a whisper, reverberated in the vacancy of the garage. “Anyway, when I pulled in, the door was about up to here”—he indicated the height of his knee—“and Peggy was right here.”

She would have been just behind her Chrysler, between her tool closet and the door that led into the house. As Railey explained how Peggy’s body was oriented—“heels here, head here”—I thought what an intimate crime strangulation is, what a gruesome and prolonged dance. “I was actually horrified,” Railey was saying. “I have never seen any such thing. Let alone my wife. Her face was purple and bloated, and her body was heaving from the waist up. Those were reflex actions, seizures, I later came to realize. I tried to shake her, tried to get some kind of response . . . and I couldn’t get anything and ran in and checked on the children. Megan was lying down in front of the television.” We walked back into the house. The family TV sat beside the picture window that looked out on the pool. “The TV was on and muted and she was on the floor and my first impression was that she was dead. I picked her up and she said, ‘Daddy.’ She had her little fingers in her mouth, and she was okay. She had evidently gotten up, looking for Mommy, and the TV was on and she laid down in front of the television.”

“Had she found her mother?” I asked.

“I don’t think so, but I don’t know.” We went through the living room to the children’s rooms. “This is Ryan’s room,” Railey said. The room was still filled with Ryan’s dolls and toys. “His bed’s been moved over to the Yarringtons,” Railey explained, “but his bed was here, and he was three fourths of the way asleep but kind of in a fog.”

That was, I remembered, well after midnight, when the children would ordinarily be sound asleep. Perhaps the assailant had thought, as I did, that strangulation is a silent crime, but who knows how Peggy may have fought, what kind of racket she might have made. Did she wake the children? The awfulness of that scene played unhappily in my mind, along with the dreadful suspicion that the person who caused this tragedy was the same polite preacher who was giving me the tour of his home.

“So anyway,” Railey continued, “I came in and called the police. I called the Yarringtons and I went across the yard and got my neighbor and he came over. He stayed with Peggy. I brought the children into the den, sat them down on the sofa with me and held them. Both were extremely quiet, ’cause they could obviously pick up on my panic. I was hyperventilating and scared to death.”

Railey and I went up to his special lair on the second floor. As a writer, I have a particular interest in the places people make for themselves to write in. Two walls were covered with floor-to-ceiling bookshelves. There was an imposing desk of the sort that would belong to a bank vice president, and a more modest work area with a computer. One of Railey’s manuscripts sat on the table. Under a dictionary stand was a copy of The Plays of Eugene O’Neill. It was a handsome office, but once again I noticed an absence of personal effects. Only two items in the room caught my eye. One was an SMU basketball on the window ledge behind Railey’s desk. He had bought the house from an SMU coach, it turns out, and had written into the contract that a basketball would come with the house. The other item was a three-foot-tall doll that resembled Big Bird. Railey said he had bought the doll for Ryan when he was in New York, and he recounted the spectacle of himself walking through the lobby of the Waldorf-Astoria with the doll under his arm. I laughed, but it struck me as curious that Railey, not Ryan, had the doll now. Railey sat in his easy chair, and I sat on a couch beside him.

“Tell me about your relationship with Peggy.”

“Well, we’d been married sixteen years. Peggy was a lot quieter than me. We had a respect for one another. We were not the kind of couple that held hands and watched television on the sofa. When we went on vacation, before the children came, and went out on the beach, we’d both take a book and read and listen to the sea gulls and watch the waves.

“We were married eleven years before we had children, and once the children came, we became more and more committed to parenting. Peggy had a great love for the church, and the impression that she didn’t enjoy being the pastor’s spouse and stuff I think is unfair to her. She was a private person and didn’t talk a lot about the inner parts of herself. I think her best friend on the face of the earth was her mother. I don’t know how else to answer. We didn’t have a lot of arguments.”

“Did she know about your affair?”

“We—that never came up.”

“She didn’t know?”

“I can only say it never emerged.”

“Did she suspect?”

Railey took a steadying breath. “I have no way of knowing, regarding that, that she suspected at all, about anything.”

I knew I was crossing the line he had drawn. I started to press further, but he cut me off. “I’ve told you I would not talk about Lucy,” he said.

“Do you plan to divorce Peggy?”

“That is not a question I will answer.”

I observed that because of his stature in the community both the church, through the bishop, and the city, through the district attorney, had advised Railey to leave town to avoid being an embarrassment to them. “I guess you could interpret it like that,” he said. “They don’t really have to ask me to leave. I just feel like I got in a situation, and it’s time for me to go.”

“Would Lucy join you?”

“I don’t care to answer that.”

“You’re going to California?” I asked. Friends of his had said that was his plan.

“No, not necessarily. I’m looking for a place to work, Larry.”

More than once, Railey asked me for information about my business, which was unsettling to me because I already felt a greater sense of identification with him than I cared to feel. Several times he had even urged me to “push harder,” to do a better job—the job he might have done on me if our roles had been reversed. We were the same age. In many ways the difference between writing and preaching was not so great; nor, really, was the difference between belief and disbelief—it was the intensity of the struggle that mattered. The lesson I had drawn from Walker Railey’s life so far was that good and evil are not so far apart either. They were both inside Walker Railey, warring for control—as they were in me as well. Whether or not Railey was guilty, he had caused me to look in myself and see the lurking dangers of my own personality.

“I’m surprised you haven’t asked about my suicide attempt,” he said, once again presuming on my role. He talked about it and began to cry. I found myself curiously removed. I began to tabulate the times he had cried so far. He had cried when he talked about the death of Bishop Goodrich. “What I was aware of”—here is the point that he cried—“was the death of tradition.” He came close to crying when he spoke about having to leave this office we were in, which was dear to him. He had cried when I asked him about his recent return to First Church for a memorial service for his baby-sitter, Janet Marshall, who had suddenly died of lupus in September. “When I walked back into the sanctuary,” he had said, “the first thing I saw was the pulpit, and I just kind of stood in the back, really, and at that point kind of lost consciousness of what was going on around me.” Later in the day, when we were at lunch, he would cry when he remembered his neglected childhood. I didn’t question the genuineness of those responses. These were real losses—of his tradition, his comfortable home, his profession, his childhood, and nearly his very life. But they seemed—what? Was it fair of me to compare his losses against Peggy’s? against his children’s? Why didn’t he cry for them?

What interested me about his suicide attempt was the note he left behind, in which he had spoken of demons. In First Church there had been much speculation about what Railey’s demons might have been—perhaps sex, certainly ambition. This is the usual Methodist metaphorical construction of biblical language. I asked Railey what demons meant to him.

“ ‘Demons,’ ” he said, “that’s just not, that’s just not a word I use a lot. I’ve talked to you about depression, that’s a demon. I’ve talked to you about a low self-esteem, that’s a demon. I’ve talked to you about a great fear over the uncertainty of the future, that’s a demon. And there may be a lot more demons, but my point is that several things I’ve struggled with would fall under the category of demons.”

“And yet your very fist sermon was ‘On Seeing Satan Fall,’ ” I reminded him. “I wonder what your opinion of Satan is. Is he a figurative creature or a real force?”

“Well, first of all, I preached ‘On Seeing Satan Fall’ because that was taken directly out of the text of the Scripture. It was a sermon on the church. I do not see Satan as some incarnated presence in life—who’s over against God and therefore the two are in a battle and we’re kind of little pawns in the game. That makes me less responsible for my own actions. I think there is evil in the world and I think there is goodness in the world and I think that both the inclinations of good, which would be godliness, and the inclination to evil, which would be satanic, are inside of us.”

“But you don’t think that at any point in your life you were controlled by forces that you couldn’t—”

“No, no, I don’t,” he said abruptly. “I think that’s a theological and a psychological cop-out.”

Railey turned the conversation back to the church, back to the moment when he had stood in the rear of the sanctuary at Janet Marshall’s service. Several years before, when Janet’s illness flared up, she had summoned her pastor to her hospital room and demanded to know what he was going to preach when she died. She had him actually write out a sermon and read it to her. “Her death became the first occasion that I was not able to do something in an ordained way that I would have done,” Railey remarked. Instead, he had slipped into the church at the last moment, hoping no one would see him but knowing that everyone expected him to be there. “There were some people who, I think—I can’t be sure of this—but there were some people who went out of their way because they didn’t know what to say. But there were a whole lot more people who did. They just squeezed, hugged, kissed, slapped me on the back. They could feel my pain,” he said, crying again. “I wasn’t able to conceal it; I wasn’t trying to. I think everybody knew that I was there under a great price, just emotionally, to walk into that sanctuary. So there was a great combination of pain but also a sense of joy that the community was there, and I felt its love.”

“Did you feel a sense of shame?” I asked.

Railey looked at me sharply. He is, of course, alert to insinuation. “I felt, probably, every emotion you could feel.”

“But did you feel ashamed?”

“I felt a great need to be forgiven, if that’s what you’re talking about.”

When he said this, it seemed to me as much of a concession as I was likely to get. We were still talking in generalities and metaphors—Methodistically, as it were—but I had the feeling that we were nearing the truth, as much as I was likely to see of it. On the other hand, perhaps I was merely twisting his words, finding more meaning than was really there.

“I felt a great need to . . . to . . . to be reaccepted,” Railey offered.

“As who you really are?” This was a leap on my part.

“As who I really am,” he agreed. “As someone who never wants to lose being part of the community that the church represents.”

“And having had that experience, do you feel now that if you”—here I searched for another word, but none would come—“I’m going to use the word ‘confess’ to whatever you are not talking about now, that they would forgive you?”

“That’s a pretty leading question.”

“It’s a hard question to ask.”

“That . . . that really . . . you—that I wish you would ask it another way,” Railey said, “because I’m not going to answer it like that. It’s just too . . . it’s too much of a setup.”

I tried to think of another way to ask, but he cut me off. “Let me just make a statement,” he said. “I was aware that night of the love that permeated the sanctuary—God’s love—in their lives. God’s love is both a judging love and a forgiving love; it’s both a healing and a haunting love. And I experienced God’s love in all four ways that night. Okay? And I think that’s about the way I would say it.”

Before I left, Railey wanted to know what I thought of him. “I don’t know what your impression is, and you don’t have to give it to me, but I’ve been real honest with you today,” he said.

I admitted that I found myself relating to him, but I also said that I could not construct an innocent man out of his behavior. I recounted his misleading testimony to the police, his avoidance of the grand jury, his inexplicable actions on the night of Peggy’s attack, and so on. “I think you’re a guilty person,” I said.

“I hear what you’re saying,” he said.

Here he was, reflecting my feelings, while I was accusing him of trying to murder his wife. I didn’t know what to think.

“I appreciate your even responding to that,” Railey continued. “I’m aware that nobody can sit down with all the facts that are supposedly known . . . and just make it all fit. That’s a frustration that everyone has felt, including me.”

“Confess,” I urged him. “It will haunt you forever, it will drive you crazy.”

“I don’t know if that’s a word of advice, a backhanded comfort, or what,” Railey said. “I am not guilty. I didn’t do it. I don’t feel tormented by the guilt of what I didn’t do.”

It would be the next day before I understood some of what disturbed me about my conversation with Walker Railey. There was, of course, the possibility of his innocence. If he was guilty of no more than infidelity, then what an awful fate for him to bear. How cruel of me to disbelieve him. But if he strangled Peggy and was going free, then what kind of person was he? I still didn’t know.

I had been struck, in a literary way, by the metaphorical parallels between Peggy’s condition and that of her children, who were in a custody limbo, and that of the congregation, which was still stunned and bewildered, and that of the crime, which continued to be unsolved, and that of Walker, who was, as I pointed out to him, suspended between one life and another. “Yes, yes!” he said with an eager intensity that surprised me. “Somebody asked me three or four months ago, ‘How’ve you been?’ And I said I kind of feel like I’m in an emotional coma. In that I’m breathing, existing, and living, but at that point—this is while I was still in the hospital—like anybody in a coma, like Peggy and others, I hear people around me talking and making decisions that affect my life, and at this point I don’t seem to have any control over those decisions. So I’m kind of in a fixed state. I guess you could say the same thing now.”

Perhaps it was the very eagerness with which he accepted this observation that chilled me, because of course there was no real equivalence between Walker Railey’s tragedy and Peggy’s. Soon after our interview he left to start a new life in California, but Peggy’s life would never start again.

And what will become of the congregation he leaves behind? It is in many respects his congregation, much of it comprising people like me, who had felt let down by the churches of their youth and who had been drawn back to faith by Railey’s radiant ministry. They shared a common belief in the goodness of Walker Railey. Now they were having to consider whether what they had taken as good was actually evil—or worse, far worse, that they would never really know the truth, and for the rest of their lives they would be bewildered, the truth would never be known, charges would never be filed, Peggy would neither die nor live again, and Walker Railey would never be revealed as either hero or villain but instead would haunt them forever, asking “Who am I?”

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Crime

- Dallas