Legislative bodies seldom live up to what the public expects of them- and certainly the 65th Legislature is no exception. Perhaps our standards were unrealistically high after the statesmanlike 1975 Legislature. That session was under the shaping influence of the ill-fated 1974 Constitutional Convention; legislators retained a seriousness of purpose that enabled them to attack many of the state’s most pressing problems. Unfortunately, this session’s dominant force was nothing so noble; it ws money, both too much and not enough. Legislators began work with $3 billion more than in 1975; it seemed more than enough to fund state agencies adequately, make real headway in achieving school district equalization, provide some taxpayer relief, and perhaps have some loose change left for a new program or, or possibly to purchase some park land. What happened instead was a scene reminiscent of The Old Man and the Sea; while legislators were contemplating how to handle their massive catch, the sharks got it first.

Every pressure group imaginable wanted a bite—from junior colleges to nursing homes—but by far the biggest appetite belonged to a tight-knit alliance of road contractors, truckers, and gasoline refiners. When Lieutenant Governor Bill Hobby capitulated on the $528 million highway bill (after insisting earlier that $245 million was enough), morale in both houses plummeted to a post-Sharpstown low. It didn’t take long for legislators to realize that there wasn’t going to be any money left for their pet projects; the only question unsettled was not how the rest of the surplus would be spent but where. As a result, though the 65th legislature will not go down as one of the most eventful in Texas history, it may well prove to be a watershed in Texas politics, the session where the old divisions into liberal and conservative camps were replaced by new alignments along urban-rural lines. This reshuffling of alliances—more than one key vote found big-city Republicans uneasy in bed with minorities, and rural white populists snuggling uncomfortably close to country conservatives—was accelerated by the types of issues before the Legislature this year, particularly school finance, but also property tax reform, county ordinance-making powers, and tax relief for agricultural property. All had greater urban-rural than liberal-conservative overtones—as will more and more of the issues that future Legislatures will face.

The unique pressures of this session made the selection of the Ten Best and Ten Worst more difficult than in previous years; not only was there little major legislation, but also there was less opportunity for members to reach the grand heights—or abysmal depths that are often achieved when ideology is involved. In simplest terms, there were fewer stars. Nevertheless, by following the Legislature from beginning to end, in the gallery and on the floor, and by interviewing legislators themselves, as well as the Capitol press, key lobbyists, state agency legislative liaisons, and prominent political figures, we were able to arrive at a consensus.

Our criteria were the same as always. We avoided consideration of political philosophy; the test of a good member is the same regardless of whether he has conservative or liberal views. A good legislator is intelligent, well prepared, and accessible to reason; because of these qualities he is respected by his colleagues and effective in his work. He uses power skillfully and to its maximum without abusing it, and without exception his integrity is beyond reproach. On issues of statewide importance he wears no parochial blinders; he is both faithful to and broader than his district. It is more difficult to summarize the attributes that qualify a member for the Ten Worst list. Stupidity and ignorance by themselves are not enough, nor is ineffectiveness. Some of the worst members have great talent and use it very effectively; that indeed, is the problem. If a consistent thread joins the worst members, it is their penchant for being sand in the legislative machinery; they are noticed primarily for being in the way.

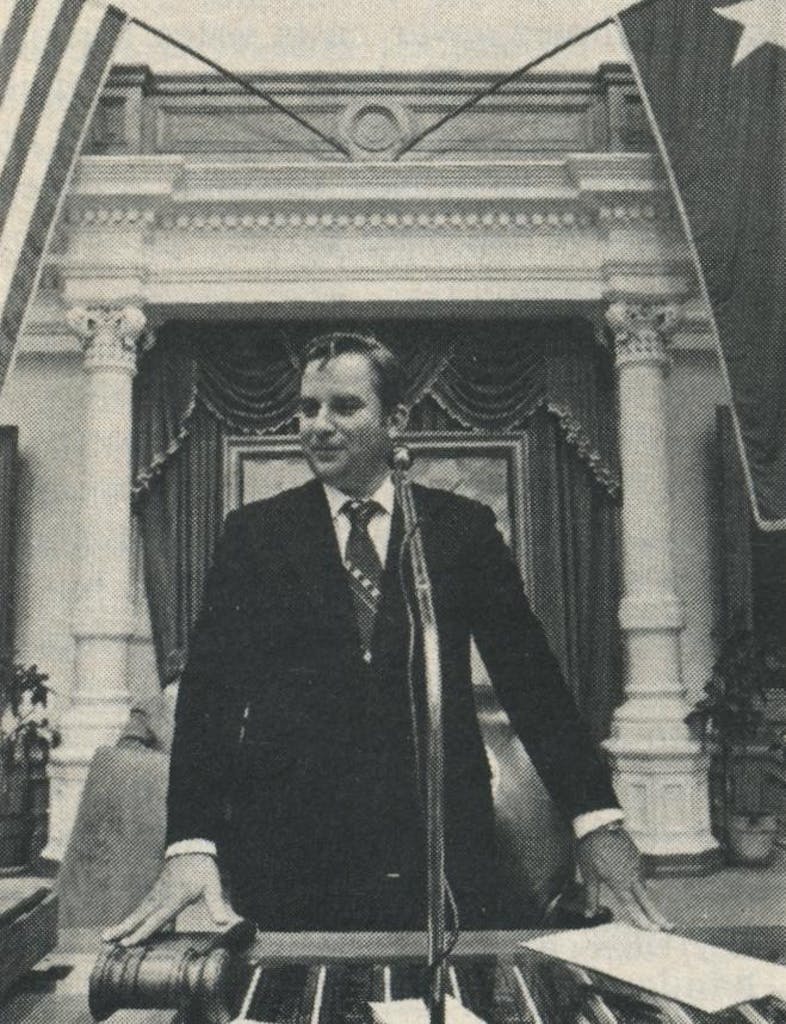

We have traditionally considered the heads of both houses ineligible for either list, but both Speaker Bill Clayton and Lieutenant Governor Hobby deserve special attention. Clayton solidified his reputation as a fair Speaker, working the House hard but letting issues be resolved without arm-twisting. He continued to be suspicious of new legislation—an attitude which fell equally on both human-and special-interest bills—yet to his credit, the House spoke to most of the session’s major issues, passing bills reforming the property tax, granting counties ordinance-making powers, and providing utility tax relief. All died in the Senate. Clayton’s most serious deficiency is that he is a politician of limited vision surrounded by politicians of even more limited vision; his team unfortunately includes some of the House’s most provincial minds.

In the Senate, Hobby is unquestionably the best presiding officer since the mind of man runneth not to the contrary. He is totally free of lobby influence and expertly informed about issues. Yet for the third straight session he ended up cast in a villain’s role on major issues; reform in 1973, utility regulation in 1975, and both tax reform and highways this year. Unlike in previous years, he could manufacture no eleventh-hour solution. Hobby’s biggest problem may be beyond his control: a senate that, sadly, is more under the influence of small lobby groups, like realtors, than any within memory.

In addition to the Ten Best and Ten Worst, a few legislators deserve special mention—honorable and dishonorable. The best legislator not to make the top ten was House Ways and Means Chairman Joe Wyatt (35, Bloomington). He ran the best committee in the House and in the process demonstrated a thorough grasp of state finances. No one this session did better work under more pressure than he did on his utility tax relief compromise, which died in the Senate’s closing hours. Someone not always taken seriously in the past, he is definitely the most improved legislator, and were he not so closely identified with a few powerful lobbyists, Wyatt would have to be one of the Ten Best. In the Senate, the only near-miss would be Don Adams (38, Jasper). Some political heavy weights rank him as “the best young senator to come along in years,” but he has yet to play a significant role in shaping legislation; instead, he’s become Bill Hobby’s right arm as head of the Administration Committee: a benevolent Wayne Hays. If there were a “They Also Served” award to a member who does his work diligently, thinks for himself, avoids entanglements with the lobby, and generally labors unnoticed, it would have to go to Republican Bob Close (47, Perryton). He’s not a star, but the Legislature could get along quite well with about a hundred more like him. Fully half of the precocious House freshman class (in addition to Ten Best recipient Lance Lalor) could be singled out; two who deserve particular attention are Jim Rudd (34, Brownfield), an oak-solid country conservative, and Republican Chase Untermeyer (31, Houston), who reasons out his votes as well as anyone in the House.

On the minus side of the ledger, the name of Emmett Whitehead (51, Rusk) leads all the rest. He did his best to make a laughingstock of the legislative process by offering the session’s most perverse bill: a proposal to build a youth correction facility next to the home of Judge William Wayne Justice, who provoked Whitehead’s wrath by handing down rulings unfavorable to the Texas Youth Council, Whitehead’s favorite state agency. Smith Gilley (37, Greenville) disgraced himself with a tempestuous eruption at a committee hearing. Cited by a conservative group for having a more liberal voting record than his district warranted, Gilley spotted the person who had compiled the ratings testifying at a hearing on the Equal Rights Amendment; confronting the unfortunate youth, Gilley began screaming epithets at him, then demanded that security guards eject him from the hearing. Freshman Leonard Briscoe (37, Forth Worth) quickly earned a reputation among lobbyists by dropping such comments as, “If I’m going to help you, then you got to help me.” Richard Slack (62, Pecos) bought the Presidio bank, then did everything in his power to keep the state from buying the nearby Big Bend Ranch—keeping it safe from private development. The saddest story in the Senate was Oscar Mauzy (50, Dallas), once a towering force, who seems to have lost his fire. Mauzy cosponsored a loan shark bill and spent much of his legislative efforts trying to feather the nest of his law practice. As the Senate’s school finance expert he started work too late, failed to work the floor to keep his committee’s version of the bill intact, then lost control of his conference committee. He yearns to be a judge; certainly he should be sent to the bench.

There was considerable turnover from last session’s Best and Worst lists. Among the good guys, only Wayne Peveto and John Wilson repeated in the House, while Senators Babe Schwartz and Max Sherman stretched their streaks to three in a row. Three other representatives retired—Neil Caldwell, Ray Hutchison, and Jim Mattox—and a fourth, Sarah Weddington, might as well have; she was almost invisible. Two other 1975 Bests again performed well but weren’t quite up to last session’s standards, Senator Grant Jones because he couldn’t get much action on his important legislative program, and Representative Bill Sullivant because he was too busy running for Speaker.

Only three-time loser Glenn Kothmann reappears on the Worst list. Senator Mike McKinnon and Representative Al Korioth lost reelection contests; Representative Larry Vick retired and fellow House member G.J. Sutton died. Representatives Fred Head and Tom Schieffer both stayed far enough out of the way to avoid repeating, though Schieffer again was an arrogant and high-handed chairman of the Local and Consent Calendars Committee. For those who believe in redemption, two Worsts were improved this session—Senator Ike Harris (despite his usual portfolio of bad bills) and Representative Tom Uher (who ran a better State Affairs Committee and earned high marks during the malpractice controversy). As for Doyle Willis, we are hereby serving notice that he can no longer expect to get on the Worst list simply by coasting on his reputation.

THE TEN BEST

John Bryant, 30, liberal Democrat, Dallas. Ended up on everybody’s best list after starting the session as a quiet, sober legislator best known for being the first officeholder in the state to support a certain Georgia peanut farmer for President. As chairman of the House Study Group, the core of “loyal opposition” to House Speaker Bill Clayton, had more influence on the session than any other member—despite everything Clayton could do to prevent it. All but excommunicated by Clayton’s committee assignments (Labor and Constitutional Amendments) and hamstrung from the start by a new House rule prohibiting the Study group from taking sides on legislation; had to rely instead on facts and figures, which have roughly the same reputation and value in the House as the lira on the international currency markets.

Converted this liability into an asset by assembling the best research staff ever to operate in the House; worked them sunset to sunrise and learned how to pick their brains to make salient points in floor debate. Nowhere was the Study Group’s impact more evident than during the appropriations debate; their detailed identification of hidden pork barrel programs forced the leadership into the embarrassing posture of repudiating their own bill; the only thing more embarrassing would have been defending it.

Had virtually no legislative program of his own, running afoul of Clayton teamers even when trying to pass a local bill, but spoke effectively to numerous issues in floor debate. Led urban resistance to proposed tax breaks for owners of agricultural property; buttressed by Study Group research, tacked on an amendment to limit the exemption to family farmers, then beat the leadership when they insisted on including corporate farms and timber interests.

Panned a little by both sides: by liberals for not being an organizer or a strategist (something they sorely lacked), and by conservatives for being, as Clayton put it, “horsey.” Did lose his temper at times; feuded with Lynn Nabers, got in a shouting match with Jim Nugent, and irritated many members by raising a dilatory point of order against the school finance bill. Made some mistakes—but not on his research; his most important legacy for the session may be to establish beyond refutation the need the competent staff.

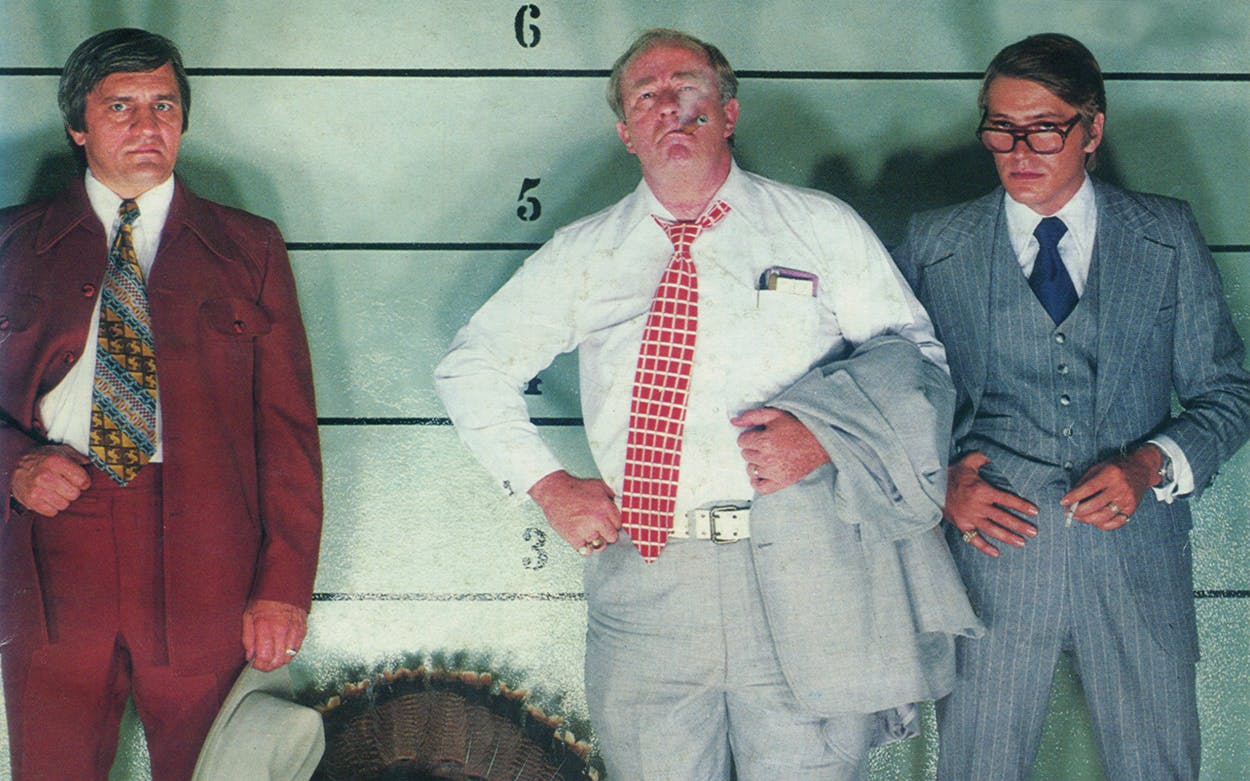

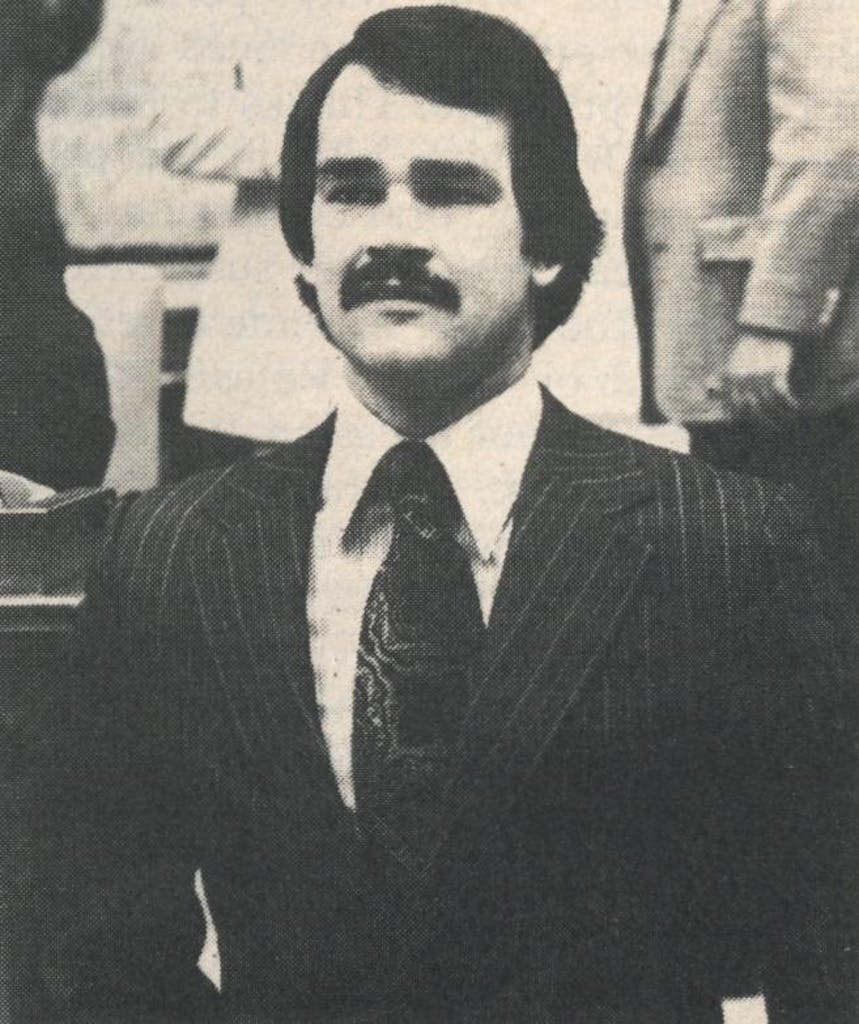

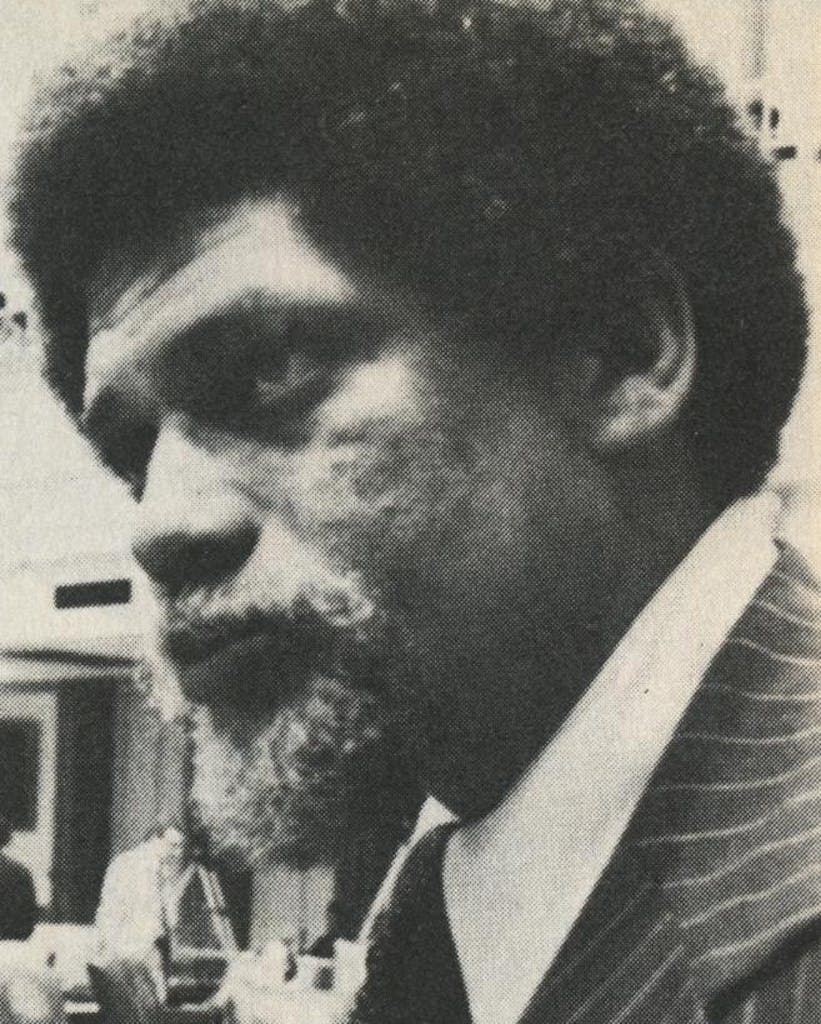

Ronald Coleman: more than a thorn in the opposition’s side, a one-man briar patch.

Ronald Coleman, 36, liberal Democrat, El Paso. More than a thorn in the side of the conservative House leadership: a one-man briar patch. Manages to be both principled and effective, a rare combination in a legislative body where the norm is neither; one of the few members called an idealist out of respect rather than scorn.

Decided at the beginning of the session to “travel light,” keeping his own legislative program to a minimum so that he would be invulnerable to retribution in his battles with the leadership.

Still succeeded in guiding through the House a bill that attempted to reserve a portion of oil and gas severance taxes in a savings account, safe from the Legislature’s itchy fingers. The sole articulate urban voice on the Public Education Committee; spent the session playing Herb Applegate to Tom Massey’s Joe Hardy, bedeviling the education chairman at every turn. Thwarted Massey’s early effort to force the House into using formulas favorable to rural school districts; was later instrumental in binding House conferees to support a key appraisal system favored by urban legislators.

Massey was not the only House power to feel Coleman’s sting. Killed a bad ole bill by Bill Heatly to give the state fire marshal (a Heatly crony) his own agency; his gutting amendment was too rational for the House to oppose. Squelched a Bob Davis power play in the closing days of the session by warning Clayton he would offer enough amendments to a controversial insurance bill to bog down the House for at least a full day.

Good at all phases of the legislative game: on the microphone, in committee, working on the floor, behind-the-scenes strategy. The best measure of his respect is that, as one of two members of the liberals’ shorthanded first team, he had to carry the ball all the time—yet despite being a marked man, he retained his effectiveness. Says a respected lobbyist: “A lot of members have been around here long enough to know what’s going on, but he’s one of the few who’s learned.”

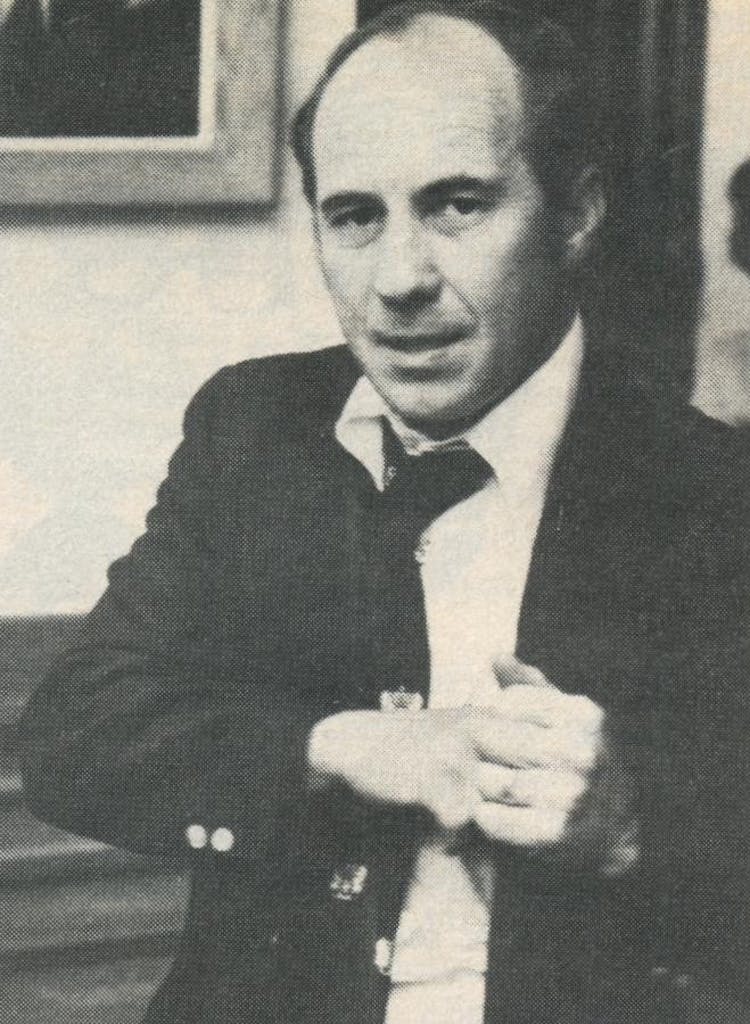

Ray Farabee, 44, conservative Democrat, Wichita Falls. All the clichés fit this rising Senate star: observers describe him as conscientious, hardworking, smart, fair, independent, someone who does his homework. These qualities apply to at least a score of legislators; yet there is something about this soft-spoken, scholarly looking senator that sets him apart—an air of inner strength, of incorruptibility, which suggests that a true legislative craftsman may be in the making.

Earned his spurs by soundly thrashing Senate heavyweight Babe Schwartz in the floor fight over medical malpractice. Their clash was the session’s most dramatic moment: the veteran with the wisdom and skills accumulated over two decades against the upstart newcomer in his first major test. Senate historians may mark Farabee’s victory (he carried the doctor’s amendments to a trial-lawyer-backed compromise bill) as the moment the torch was passed to the upcoming generation of senators.

Carried a small but important legislative program, including a bill to provide a method of financing the revitalization of blighted downtown areas. Conceived, drafted, and passed a “natural death with dignity” bill for terminally ill patients: it was one of the few major bills to become law without the help of organized support—mainly because Farabee lobbied it through the House himself. Also carried a crucial worker’s compensation bill that required delicate handling in both houses.

One of a regrettably small handful of senators who can’t be seduced, coerced, or otherwise convinced to support sleazy bills (voted against loan sharks, insurance sharpies, and the more outrageous realtor positions). If he has a flaw, it’s that he is still unsure of himself. Showed signs last session of resisting the logrolling and pork barreling so prevalent in the appropriations process; performed well on the Finance Committee again but not longer seemed willing to question the system. Like Max Sherman, tends to be less conservative than his district (though neither is a liberal by any stretch of the imagination) but, unlike Sherman, hasn’t learned how far to follow his instincts.

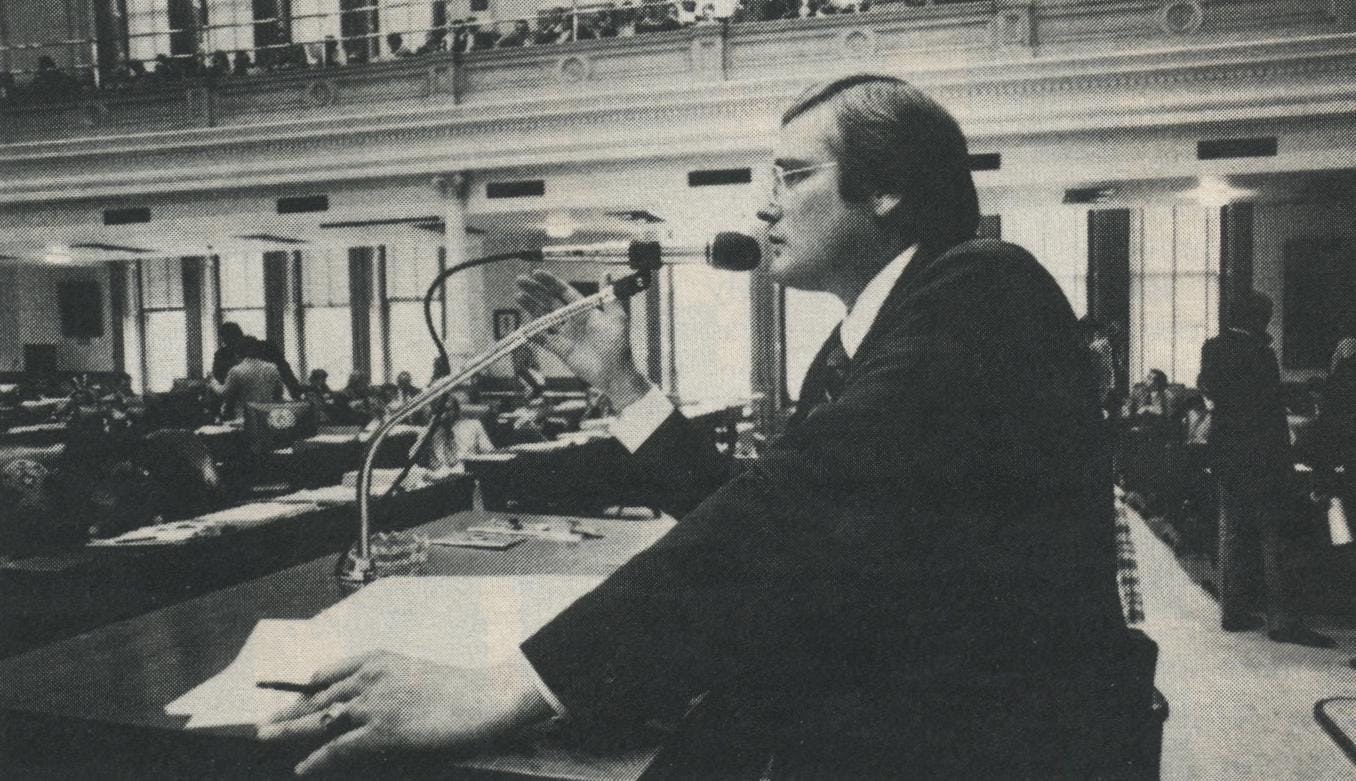

Lance Lalor, 30, liberal Democrat, Houston. The best member of the best freshman class to hit the Legislature in years. A rarity in Texas politics: a liberal free of ties to the usual liberal pressure groups (labor, trial lawyers), who spends his time working instead of complaining how bad things are.

And does he work! Before the opening gavel, Lalor knew the rules—written and unwritten—better than many veterans. Seldom left the Capitol before midnight; one House staffer who worked nights analyzing the calendar tells of running into Lalor in the halls at 3 a.m. on more than one occasion.

Refused to stay quiet and observe House protocol, which calls for freshmen to stay quiet and observe House protocol. Passed an unusual number of important bills for a first-termer, but equally important, killed or maimed bills sponsored by old pros. Smart enough to pick his spots; didn’t rant and rave, so was not stigmatized as a kneejerk liberal.

Passed the first arts and humanities legislation in a dozen years. Wrote the tightest, most inclusive of the numerous sunset bills to terminate state agencies automatically unless they can justify their existence, then outmaneuvered veterans John Wilson and Lloyd Doggett to get his bill substituted for their weaker versions. Passed the most important consumer legislation of the session, a constitutional amendment to increase the jurisdiction of small-claims courts. Did his best work on the Electons Committee, where he was involved in two memorable jousts with thirteen-term fixture DeWitt Hale.

Earned the nickname “Ken Doll” because of his lacquered appearance. Not an ounce of good ole boy in him: a no nonsense loner whose attitude was well nigh unbearable to some, but while his detractors were gorging on the lobby’s whiskey, Lalor was studying the next day’s work.

Regards the lobby as leprous, untouchable: unfailingly returns or gives away their petty offerings, such as honey, chili, and belt buckles; religiously boycotts their parties. Chief problem is intolerance of fellow legislators who refuse to put in eighteen-hour days or fail to understand why he does. Still, in a body where zeal is found mostly in demagogues and fools, it is a relief to find it allied with good sense.

Lynn Nabers, 37, conservative Democrat, Brownwood. Perhaps the only member of the Clayton team who could stroll around the Capitol after midnight without getting mugged by other legislators; a rara avis in the legislative dovecote: a team player whose decency and independence are unquestioned.

Has come a long way from the days when he was known only as (1) Ben Barnes’ successor and (2) the author of pecan-thrashing legislation. Carried a thoughtful, weighty legislative program, which included cosponsorship of the refinery tax, a school tax reform bill, and higher severance taxes on oil and gas—hardly a typical repertory for business-oriented West Texas types, but then Nabers is strictly a cottage-industry man. None of his far-reaching legislation made much progress, but as one lobbyist said, “Nabers is smart enough to know that in politics you can’t kick a door down, you’ve got to wedge it open a little at a time.”

Chosen by Clayton to replace Craig Washington as chairman of the Criminal Jurisprudence Committee in order to ease the passage of Governor Dolph Briscoe’s anticrime package; surprised everyone with his careful, reasoned treatment of the law and order bills. Resisting enormous pressure from the governor, Nabers refused to wave the bills through with only perfunctory analysis, despite his announced support of them in principle. Thanks to Nabers, the more Draconian bills in the package—wiretapping, oral confessions, evidentiary searches—were subjected to voracious study and, in some cases, dissection and/or death. Votes with the Clayton team, but occasionally takes an independent tack, as when he voted not to table an amendment raising the welfare stipend for dependent children.

Holds to the best virtues of rural conservatism (fiscal soundness, respect for law and order and individual liberties, and a healthy suspicion of institutions that are too big and too powerful) without yielding to the vices (lobby hypnosis, parochial views) that so often warp conservatism in Austin. Has potential to grow into a Man for all Regions, but there is talk this was his last session; if so, it also was his best.

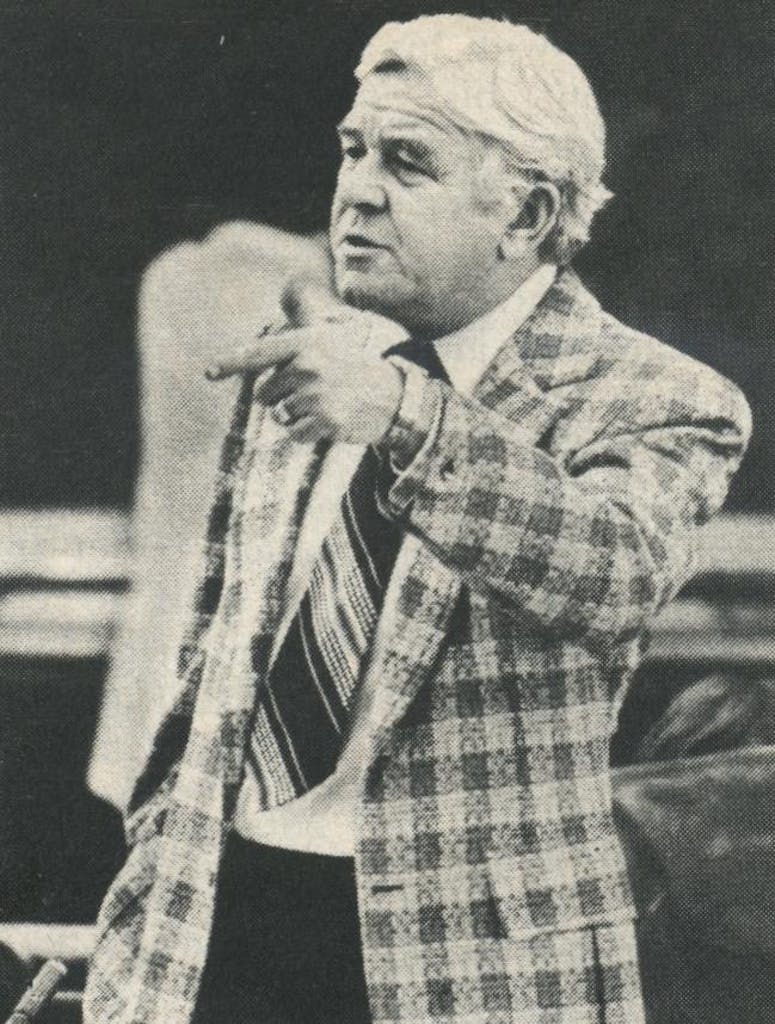

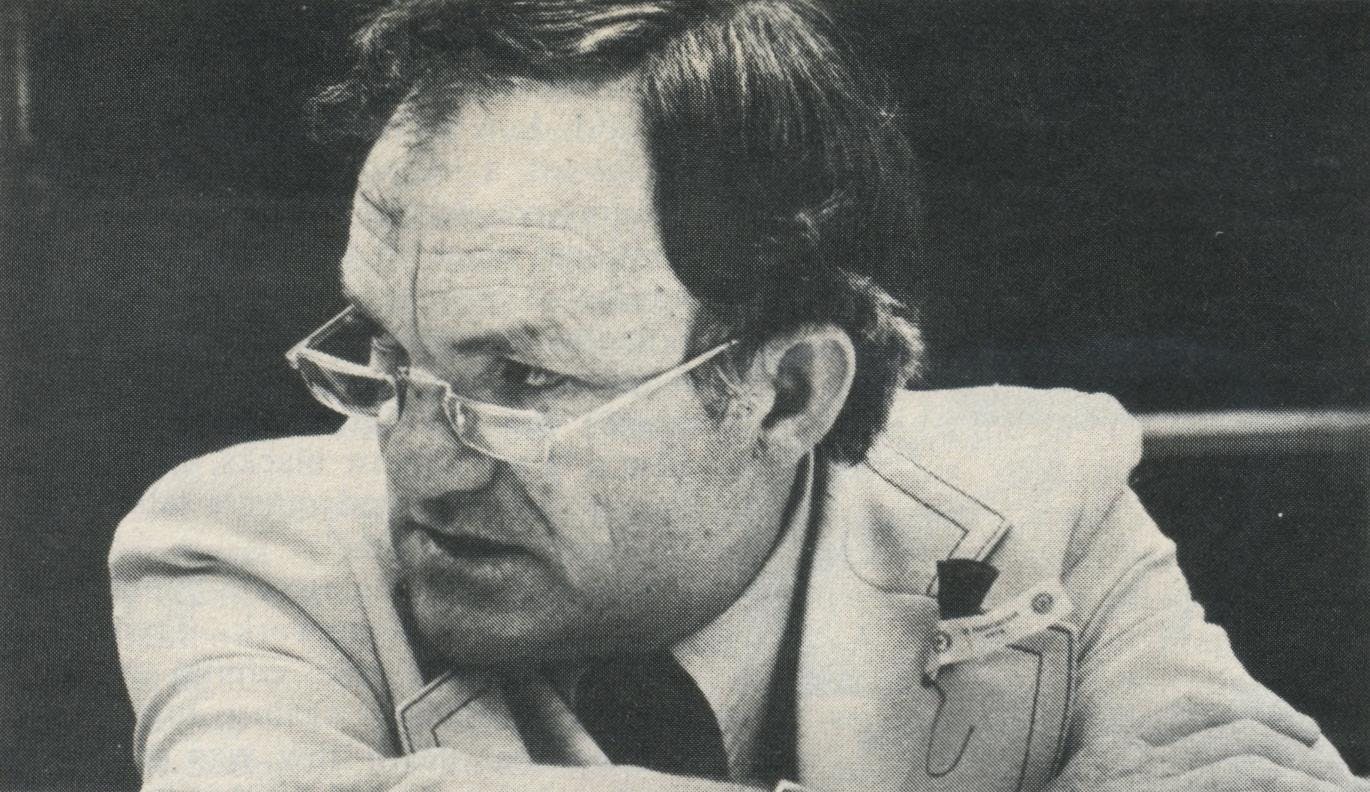

Jim Nugent, 55, conservative Democrat, Kerrville. The most effective member of the House, and the most feared. Known to his colleagues as “Supersnake”; this session was more super than snake—though there are those who insist it was close.

Carried the highway bill as chairman of the Transportation Committee, skillfully fending off attacks from liberals complaining it was too much and conservatives complaining it was too soon. Position on Education Committee spelled big trouble for the Texas State Teachers Association (TSTA), which committed two very stupid mistakes last year: they ran a candidate against him, and they didn’t win. Got his vengeance by questioning the soundness of the Teacher Retirement System, a ploy that kept TSTA busy protecting their flank when they should have been fighting the highway bill.

A legislator of amazing breadth; few pieces of major legislation got out of the House this session without carrying extra baggage added by Nugent. Among the bills he amended: malpractice, county ordinance, and coal slurry. Said one staffer: “All he has to do is walk around with a file folder during debate and other members start worrying.”

Very hard to figure out—and does everything he can to keep it that way. Fiercely protective of his independence and displays it in little ways: one of the few conservatives with a liberal staff; has a strong feminist as chief aide—but that didn’t stop him from quashing a proposed commission on the status of women. Not part of the Clayton team; they, like everyone else, come to him.

His reputation is the source of his power; long ago let it be known he was capable of anything, so is seldom tested. Cultivates the image of a parliamentary Bobby Fischer, who can see so many moves ahead that he’s playing a different game from everyone else.

Despite his nickname, has absolute, unquestioned personal integrity; doesn’t like to deal with lobbyists (a feeling that is mutual) and, unlike many lawyer-legislators, never mixes his legislative and professional business. A Best who was on the Worst list four years ago, and for many of the same reasons; is there anyone in any legislature anywhere who is harder to categorize?

Wayne Peveto, 38, conservative Democrat, Orange. Poor Wayne Peveto. Did the best preparation on the best and most important bill of the entire session—only to be thwarted by senators beholden to the real estate lobby. In integrity and motivation, towered over Tom Creighton and other opponents like the Colossus over Rhodes, but in the end couldn’t beat the system.

Has labored most of his legislative career for what has become known as the Peveto bill, a property tax reform measure that would accomplish a lot of things no one understands but everyone agrees are necessary. Spent hundreds of hours between legislative sessions drumming up support for a bill that couldn’t possibly advance his political career one iota: it was too complicated, too devoid of sex appeal, and had too many organized enemies and too few organized friends. “He’s number one on my list,” said a House staffer. “He worked his heart out on a problem that’s a slow motion Watergate—and he did it for no other reason than it was right.”

Displayed his legislative skills maneuvering his bill through the House; knew when to compromise and when to stand firm. Has an ingenuous, countryboy style that once lulled opponents into underestimating him, but no longer. Generally votes with the Clayton team but thinks like the liberal House Study Group; refuses to join either one. Challenged the leadership on the highway bill, producing figures to show that it would eat up the state’s surplus and wreck plans for tax relief, and on appropriations, where he attempted to send the pork-barrel-laden bill back to committee. Score: Windmills 2, Peveto 0.

Criticized last session for failing to play hardball; this time went down to defeat with his cleats on. Took on Creighton, Hobby, and the entire Senate in a desperate effort to pass his bill—a fight he was doomed to lose, but one that will make him even more of a force to be reckoned with the next time around.

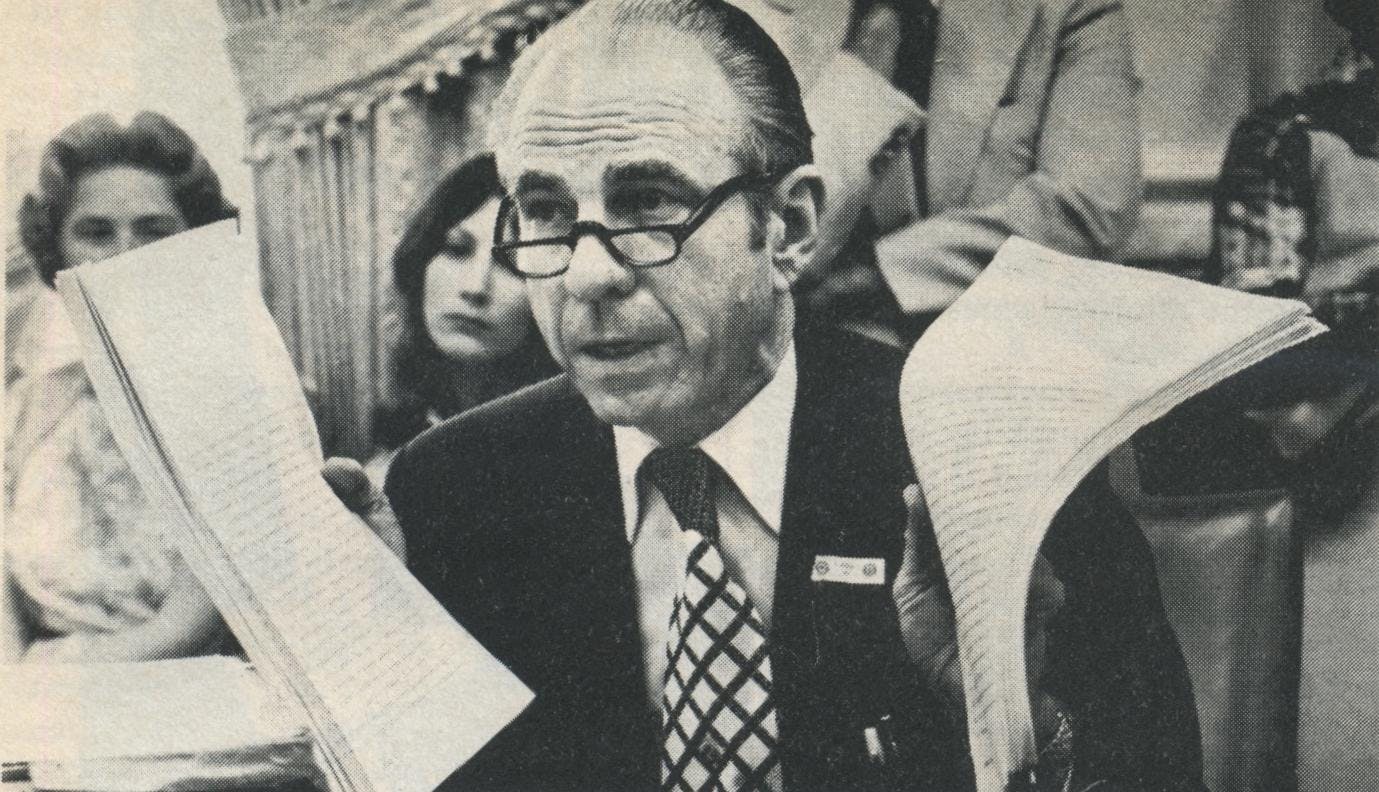

A.R. “Babe” Schwartz, 50, liberal Democrat, Galveston. Along with Max Sherman, making his third appearance on the Ten Best list. The same as always: a scholar on the rules, a master at the fine art of passing bills, and a connoisseur of when to put his hand in the appropriations cookie jar.

Best known outside the Legislature for his flamboyant pronouncements on any subject; fits perfectly a characterization originally assigned to Teddy Roosevelt: when he attends a wedding, wants to be the bride; when he attends a funeral, wants to be the corpse. But learned long ago not to mix his love for headlines with his fondness for passing legislation; his speeches are always about someone else’s bills.

Amid all the hubbub over the governor’s anticrime package, few noticed that Schwartz passed the two most significant law and order bills of the session: a statewide adult probation program and a shock probation act to slap first-offense probationers in the penitentiary just long enough to let them figure out they don’t want to come back; also passed a bill restoring felons’ right to vote. Active as usual in coastal legislation: passed a coastal management package, including a controversial wetlands act; a save-the-redfish bill; and killed a developer-backed bill to shut off public beaches to motor vehicles.

A ferocious opponent in floor debate; the mere threat of a Schwartz filibuster was enough to kill several bills and force amendments onto several others. At his best in two losing efforts: malpractice (where he initiated his opposition to a doctors’ amendment with, “I rise to speak against the amendment and for the children”) and highways (where he pierced opponents’ claims that the Senate version was cheaper than the House bill with, “You can look at this as a $300 million saving or a $600 million boondoggle”).

Unsheathed a little-used weapon in a politician’s arsenal—the ability to discern right from wrong—and flailed his colleagues for their failure to do the same. Respected but not revered by the bland, colorless younger generation of senators: he will always be someone who alienates one side when he speaks out and another when he doesn’t.

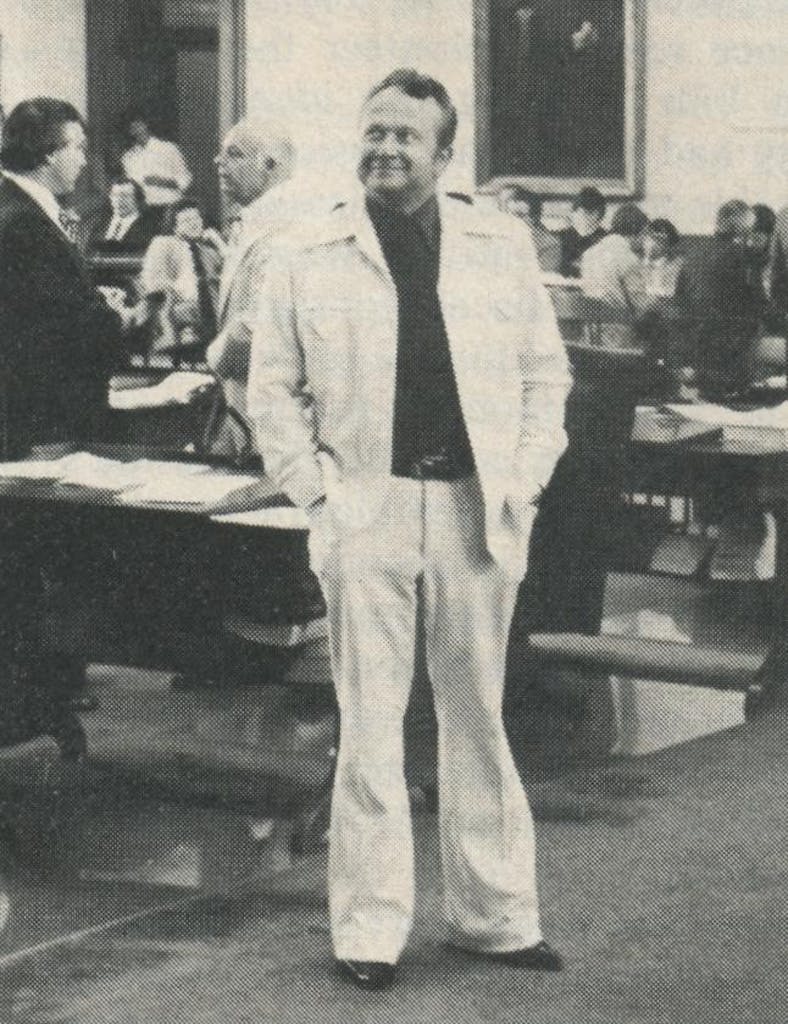

Max Sherman, 42, conservative Democrat, Amarillo. The unanimous choice as the best member of the Legislature: a walking boy scout motto. Completely open and without malice, guile, or misplaced ego—almost too good to be true. Indefatigable: after Bill Meier’s record-shattering filibuster, when other members were heading exhaustedly for home, Sherman went out and ran seven miles. Knows Senate staffers by their first names; drinks no whiskey; runs the best committee in the Senate; and assumes major roles in complex issues like school finance even though not on the committee responsible for the legislation.

Worked so hard and efficiently, he made other chairmen appear snarled in Rube Goldberg equipment. As chairman of the important Senate Natural Resources Committee, by May 1 had held hearings on all 189 bills sent to his committee; two-thirds were reported favorably. Served on two other committees that had the session’s heaviest work loads. Finance and Jurisprudence, and still found time to pass 100 per cent of his own legislative program through the Senate.

The leading Senate energy spokesman (he drives a 1960 Volkswagen), yet completely free of oil and gas lobby ties—and unprecedented feat. Major achievement this session: passing the coal slurry pipeline bill through the Senate despite heavy opposition from railroad lobbyists. Also passed a bill to involve first-line state officials, rather than bureaucrats, in energy planning. Most important nonenergy legislation was a speedy trial act that should benefit both the state and the accused.

At his best on matters that involve the essence of politics: compromise and fairness. A staple choice on any controversial conference committee; served this session on malpractice and school finance, the two most volatile. Respected most of all for his independence. “He is nobody’s puppet,” says one lobbyist who is an expert at finding strings. A servant to his district but not a slave; never casts votes for parochial reasons. If there is any criticism, it’s that he’s not a scrapper, but with his ability to reason through problems, he seldom has need to be.

John Wilson, 37, moderate Democrat, La Grange. The Legislature’s biggest star two years ago (as leader of the fight for a strong utilities commission); had a very different session this time. Didn’t live up to expectations but still merits selection because of his immense skills and considerable impact on legislation and strategy.

Active behind the scenes in two of the session’s most crucial battles. Somehow persuaded Briscoe’s staff to join the fight against Charles Evans’ bill to handcuff the governor’s arch rival, Attorney General John Hill. Helped break a stalemate over appropriations by convincing the leadership to take the initiative in paring fat from the bill.

Has no peer in the House on understanding issues; nothing eludes his grasp. Probably the only member capable of producing his comprehensive energy package (covering everything from conservation to phasing out natural gas as a boiler fuel). Didn’t make much headway this time but undoubtedly established the standards for next session.

Very strong in floor debate, with a quick, agile mind capable of penetrating to the core of any problem. Once appeared immersed in a Wall Street Journal clipping while the school finance debate droned on in the background; suddenly leaped to his feet, raced to the microphone, and pointed out a tax loophole others had overlooked. Effectiveness is enhanced by his peculiar style of, as one newsman wrote, “grabbing the lectern with both hands, as if trying to steady a pitching rowboat.”

Unfortunately, appeared more interested in not rocking the boat than in piloting the ship of state. Considers himself a rural populist but this time was more rural than populist; spent the session waiting for his kind of issues to come along, but they never did. At his best battling large concentrations of economic power (bank holding companies, utilities, major corporations): instead found himself fighting school aid equalization, property tax reform, and county ordinance power. Lost stature with independents by making gratuitous, demagogic gestures on peripheral issues like gun control; they began to view him as a political contortionist who sets his feet in one direction and his face in another, so that no one knows which way he will go. If and when he decides, he could just as easily end up a Worst as a Best.

THE TEN WORST

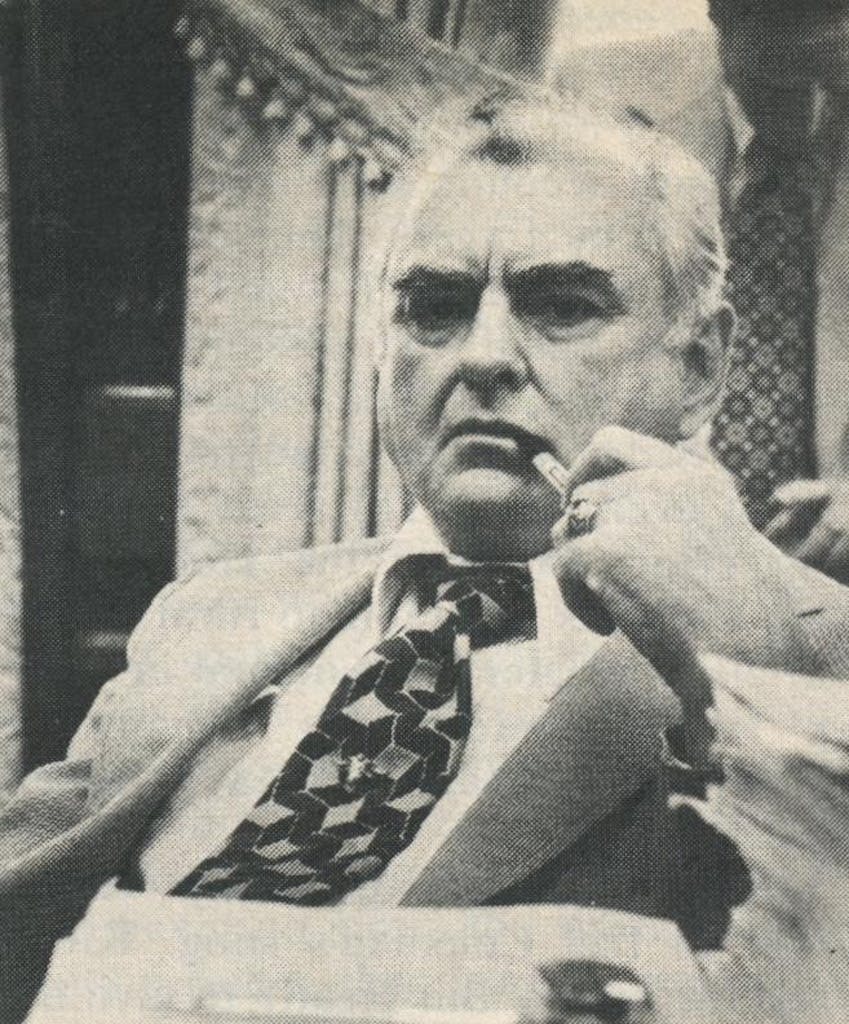

Tom Creighton, 50, conservative Democrat, Mineral Wells. Edmund Burke would turn over in his grave at the thought of sharing the conservative label with this veteran water carrier for the Austin lobby. An old-line senator whose only philosophy is to do for your friends and to everyone else.

Ran the worst, most arbitrary committee in the Senate—a feat of staggering difficulty, since he was competing with, among others, the legendary Bill Moore. Bill after bill went to Creighton’s Economic Development Committee for a routine checkup, only to be pronounced DOA. Among Creighton’s more outrageous tactics: canceled a hearing on an important bill he opposed because a filibuster was taking place, even though committees routinely meet during filibusters; capriciously sent a bill that was pending business to the bottom of the calendar; and refused to set hearings on controversial bills before mid-May—so late they couldn’t possibly pass.

Outdid himself on Wayne Peveto’s property tax reform bill, which he had pledged to move to the floor. Promptly reneged—such promises, to Creighton, are just another treaty with the Indians—setting off enough fireworks to insure that when the bill finally did get out of committee it had no chance. Taunted the bill’s backers by promising to set it for consideration June 1—one day after final adjournment.

Not every bill had trouble in Economic Development; those with strong lobby support came flying out. Loan shark bills, real estate bills, flimflam insurance bills: all got prompt hearings and quick approval. “That committee ought to be called Economic Benefit,” said one senator. “It never worked on bills—no amendments, no substitutes—just yes on lobby bills and no on everything else.”

Compiled an equally cynical record on the powerful Finance Committee. Masqueraded as a fiscal conservative when convenient; switched completely when his pet causes were under consideration. Voted for a bill giving the Railroad Commission new authority to set gas rates, then rejected the commission’s request for additional funds to hire adequate staff; the beneficiaries of such ill-placed fiscal responsibility, as Creighton well knows, will be not taxpayers but soon-to-be-underregulated gas utilities.

The type of conservative whom Disraeli described as offering no redress for the present and making no preparation for the future. Anyone writing a book on what’s wrong with the Texas Legislature could do worse than follow Creighton around.

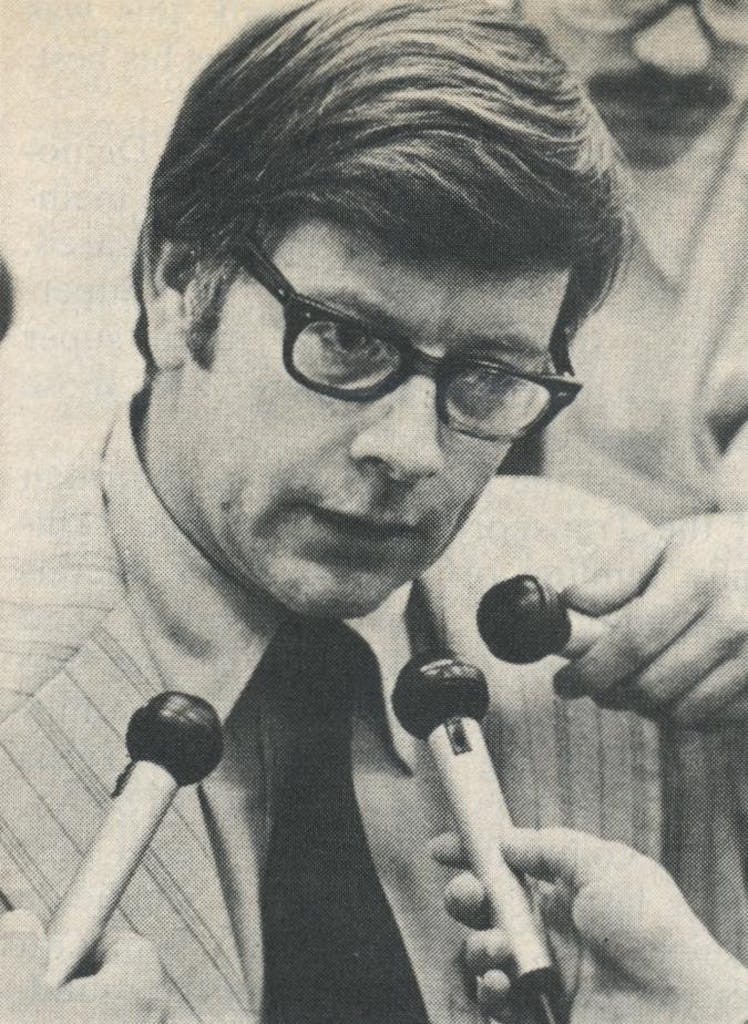

Bob Davis, 35, Republican, Irving. Exceedingly able but degrades his talent into virulent disruption. Has verbatim command of House rules, but too often uses them gratuitously to embarrass and humiliate a colleague. Knows insurance law better than any other member of the Legislature, but puts his knowledge to work only on behalf of the industry. Peer to Jim Nugent, the top House practitioner of political hardball—but, while Nugent pitches curves, Davis slings beanballs.

A terrible lobby mooch. His favorite gambit: get a group together for golf, then seek out some lobbyist whose country club membership he can use. Prefers a local course known as Onion Creek because, says one lobbyist on whom Davis frequently puts the bite, “that’s where the big wads play.” Adds a veteran legislator: “He wouldn’t use a pay toilet without asking a lobbyist for a dime.”

One does not traffic with the lobby on a one-way street, of course, and for Davis the return trip is routed through the House Insurance Committee, which he chairs. “Nothing comes out of that committee that the insurance industry isn’t for,” says a neutral observer who watched Davis’ committee all session.

Faster with a blackjack than a Houston cop; never uses a scalpel when a knife will do. Perverts the normal give-and-take of the legislative process; his wheeling and dealing is unencumbered by any sense of self-restraint. Appointed by Clayton to the key Calendars Committee, then exploited his position to make offers his colleagues couldn’t refuse—not if they wanted to pass any bills. Used his Insurance chairmanship to make deals with committee members; a typical Davis bargain usually offered crumbs in return for a whole loaf, as when he promised to let a colleague’s bill out of subcommittee (giving Davis a second shot to kill it in the full committee), in return for the member’s pledge to vote a pet Davis bill out of the full committee to the floor.

In the closing days of the session, shocked even veteran lobbyists—perhaps a first—by attempting to hold a noncontroversial bill hostage in order to further his political ends. House Bill 712 was backed by life underwriters, who—along with just about everyone else—were opposing a highly controversial bill Davis favored. Despite the fact that HB 712 was uncontested and had passed both houses, Davis found a stratagem to kill it, then warned underwriters that unless they pulled down the opposition, HB 712 was dead. (Clayton put an end to the ploy under pressure from Ronald Coleman.)

Has vowed publicly that State Board of Insurance Chairman Joe Christie will not get to campaign for the U.S. Senate against Davis’ GOP chum John Tower on a platform of insurance reform. Set out to keep his word by pushing bills to strip the board of its power to regulate fly-by-night accident and health policies, and eliminate its regulatory authority over Blue Cross. After a session-long effort, finally succeeded in chopping Christie’s budget by $1.5 million.

Charlie Evans, 38, conservative Democrat, Hurst. Has the dubious distinction, originally awarded to former South Carolina Senator Cole Blease, of combining in one person all the disadvantages of the democratic form of government. Arrogant, inept, bullying, pompous, and closed-minded.

Stumbled into prominence early in the session when he tried to strip Attorney General John Hill of the ability to protect consumers against price fixers. Rushed the bill through his Judicial Affairs Committee and onto the floor, where it remained just long enough for him to show he didn’t understand the legal issues at all; then was forced to rush it just as quickly back to committee in order to forestall a humiliating defeat. Spent the rest of the session picking nits with Hill to gain some measure of vengeance; worked overtime to chop the attorney general’s budget—but to no avail.

Like a man riding backwards in a train, he never saw anything until it had gone by. A truant when it came to doing his homework, causing one colleague to speculate that Evans refused to study bills as a matter of principle. Presented a sunset bill to the State Affairs Committee but had little idea what was in it; was cajoled into dropping an amendment to the county ordinance bill by one of the oldest tricks in the book—a member’s bland assurance that the language was already in the bill.

Mystified observers of his committee by repeatedly asking dumb questions from the chair. Once questioned a variance in the authority of a new court, saying that he had never heard of the procedure before; a lawyer in the audience rose to volunteer that half a dozen bills granting the identical authority had passed last session.

Unable to resolve the classic dilemma of Texas conservatives, who for ages have endorsed fiscal conservatism in principle only to knuckle under in practice to special-interest groups at the first twist of the arm. By the session’s end, Evan’s arm resembled a numbernine screw. Quickly abandoned interest in a bill to consolidate government purchasing when opposition flared from small businessmen. Also dropped an important bill to reorganize welfare agencies when health care lobbyists raised the red flag.

One of the Legislature’s most vindictive members. Spent long drinking hours discussing vendettas he had brought to a satisfactory conclusion over the past ten years and future plans to “get” those who opposed him this session. That should keep him busy.

DeWitt Hale, 60, moderate Democrat, Corpus Christi. No one in Texas politics can take much pleasure in finding DeWitt Hale among the Ten Worst legislators, but nearly everyone puts him there. After thirteen terms, in many ways he personifies the House as an institution; has a proud record of achievement in areas like education and judicial reform, but his accomplishments are all behind him.

One of the Ten Best four years ago; in steady decline ever since. Still makes a lot of noise, but nobody listens: his influence has turned sour, partly due to age, partly due to his unabashed advocacy of special-interest legislation. Long ago crossed the line separating mere sympathy for a lobby group from promiscuous espousal of its cause, but this was his most shameless session.

Passed over by Clayton for a committee chairmanship despite his long experience, he spent the session as the realtors’ point man. Succeeded in passing a tax break for condominium owners but got clobbered in a battle to “reform” old loopholes in campaign contribution laws and carve out new ones. Lost the latter in an uncharacteristically inept performance on the floor: misunderstood one amendment, lacked his opponents’ grasp of current election law, and finally resorted to denouncing their criticism as “nit-picking detail.”

Reputation as a mouthpiece for special interests has diminished his effectiveness on the microphone; has even less influence one-on-one, where, says one member, “He’s terrible to talk to. He just rambles.” Says a former admirer: “He’s behind only Hubert Humphrey and Ralph Yarborough on the list of boring politicians.”

Even fell flat in areas where he once went virtually unchallenged. Outmaneuvered twice on the rules (the rough equivalent of Julia Child losing a bakeoff…), once on a rule he himself had written (…on her own recipe). Had virtually no impact on education for the first time in memory—though it wasn’t because he didn’t try. Lost badly in trying to set aside money from the school finance package to reserve for teacher salary increases; outgunned in committee on teacher retirement (Hale wanted to set aside more money for active teachers; Jim Nugent favored teachers who were already retired; Nugent won).

His ebbing skills call to mind Cromwell’s words to the Long Parliament: “You have sat here too long for any good you have been doing. Depart, I say and let us have done with you.”

Glenn Kothmann, 49, liberal Democrat, San Antonio. Hopelessly inept, an embarrassment even in a lackluster Senate. So idle he should be eligible for unemployment compensation; kept his colleagues in suspense wondering if he could go through the whole session without introducing a single bill (he did). His entire legislative program consisted of a lone resolution welcoming a government class from Saint Mary’s University, which, one can only hope, was visiting the Capitol for reasons other than observing Kothmann at work. So seldom participates that when he was actually seen speaking on the Senate floor, word raced through Senate offices, and staffers rushed to view the rare moment for themselves.

So lacking in skills that he occasionally has to solicit help in answering his mail. Faced with an angry letter from an important constituent. Kothmann took his “tough problem” to another senator, who directed his own staff to draft a reply, then edited it himself, before entrusting it to Kothmann for his signature. On the infrequent occasions when he has to make a procedural motion, invariably must be coached through it by other senators.

Tries to justify his inactivity by posturing as a “bill killer, not a bill promoter,” but the fact is that the lobby universally regards him as an easy mark, even for the sleaziest bills. Voted for two of the session’s worst: the loan shark bill (despite confessing publicly that he didn’t know what it was all about—a curious position for a self-anointed watchdog) and a bill to strip the State Board of Insurance of power to mandate minimum benefits for health policies. Not for sale in the traditional sense, but regards his acceptance of a campaign contribution as an unwavering commitment to the donor. “He stays hitched, he does do that,” says one of Austin’s most prominent lobbyists.

His indifference to issues is legendary. “Never talk about the merits of a bill with him,” says a higher education lobbyist. One feminist was startled when Kothmann interrupted her explanation of women’s issues with: “You know, I’m a bachelor, and I keep in great physical shape. Want to feel my calf?”

As the only member of the Legislature to make the Ten Worst list three sessions in a row, Kothmann retires the trophy. If only his constituents would do the same for him.

Tom Massey, 46, conservative Democrat, San Angelo. If, as H.G. Wells wrote, history is a race between education and catastrophe, then let it be recorded that Tom Massey is on the wrong side. As chairman of the House committee charged with writing a school finance bill, had the hardest job in the Legislature—and wasn’t up to it.

The wrong man in the wrong place at the wrong time. “He was out of his depth, intellectually and politically,” said a sympathetic member. Produced an education bill that addressed the issue of equalization by giving more money to rich districts than poor districts. Handled the one issue this session that affects everyone, everywhere, and took the narrowest view possible. If one word could describe the reaction of school finance experts to the House bill, it would be: appalled.

Insisted on a method of property valuation detrimental to urban areas, despite the fact that his own resolution mandating its use had already been soundly beaten on the floor—the first, but far from the last, time he would be drubbed in floor debate. Bested by Ronald Coleman on full state funding of kindergartens (Massey was opposed): so lost control of his meager teacher pay raise bill that the House was treated to the pathetic spectacle of the author casting one of only four votes against his own bill.

Seemed to spend the session in a daze. So over his head in the school finance conference committee that he was lucky not to end up on the bottom of the pool; senators easily outmaneuvered him on important procedural points. Couldn’t figure out how to oppose a bill to provide state aid for parochial school textbooks: let it out of committee, then watched incredulously as the House reached the verge of passing it; at the last minute rose in opposition, sputtered his way through an argument, and finally had to be rescued by a Nugent point of order.

A few members attributed Massey’s rural bias on school finance to his desire to run for Bob Krueger’s West Texas congressional seat, but most didn’t give him that much credit. Spent much of the session complaining about his lot, saying things like, “this session is no fun for me. It’s just a hell of a bunch of work.” May not be the first legislator to knock his brains out against a wall, but must be one of the few to build a wall expressly for the purpose.

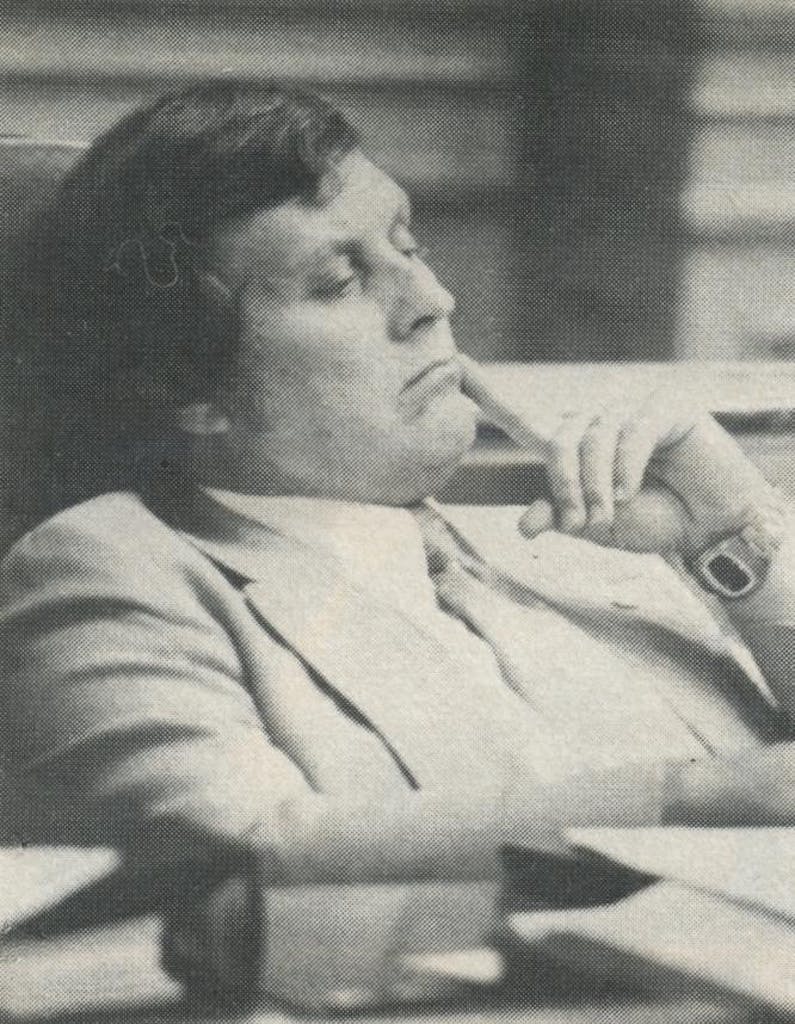

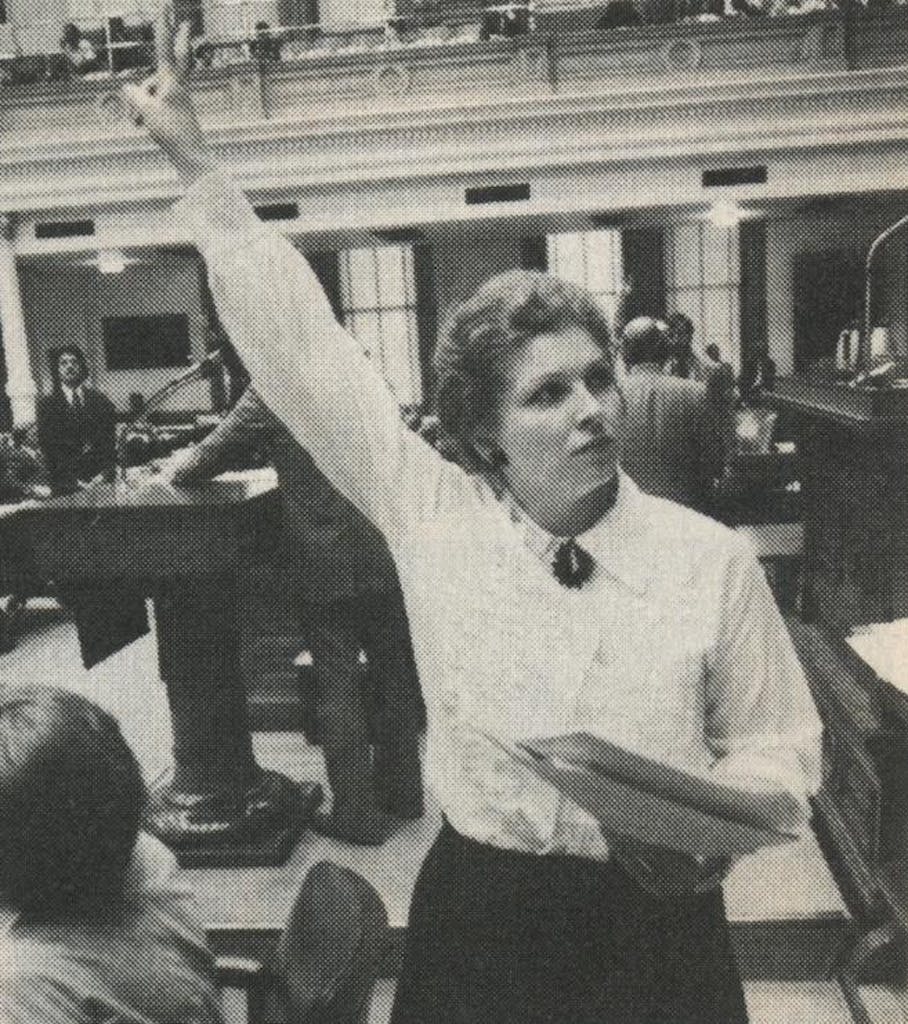

“Chris Miller, 51, liberal Democrat, Fort Worth. It was Conrad who wrote that “no woman is a complete fool,” but it was Chris Miller who this session set out to prove him wrong. The archetypal ineffectual liberal, not because she lacks intelligence or energy, but because, in the words of one Capitol veteran, “She has less concept of what’s going on than my eight-year-old.”

Shoots from the hip with a pistol normally loaded with blanks. During the appropriations debate, tried to transfer funds from a brucellosis inoculation program to hemophiliacs; when questioned, confessed she didn’t have the faintest idea what the brucellosis program was, but “it looked like a good place to cut.” After her amendment flopped by four votes, a bitter fellow liberal (who knew the brucellosis program was a blatant pork barrel dole to cattle ranchers) sighed, “Anybody else could have passed that amendment.”

The type of politician who approaches problems with an open mouth instead of an open mind. “She takes a position too quickly, then won’t back off,” says a lobbyist who can usually count on Miller’s vote. Adds another: “You can’t explain anything to her; she’s aggressively obtuse.”

Sometimes appeared to deliberately refuse to understand, as when she voted “present” on an uncontested local bill in committee—a tactic that alienated the bill’s sponsor for the rest of the session. So lightly regarded that a senator had to lobby the House personally in order to resurrect a bill he had unwisely entrusted to her care.

Works hard to misconstrue the most innocent occurrence of sex discrimination; berates colleagues unlucky enough to use the masculine pronoun to refer to both sexes. Says one feminist staffer: “She hasn’t learned yet how to disagree with these people. Her relationship with other women is no better than it is with anyone else.”

Wants to run for the Senate, an ambition that causes Tarrant County politicos to shudder at the thought of a race between Miller and her bumbling Senate colleague, Betty Andujar. The only parallel for such a contest is the old tale of a debate between two maladroit politicians who “engaged in intellectual combat today. Both were unarmed.”

Bill Presnal, 45, conservative Democrat, Bryan. The genial pork-barreling chairman of the House Appropriations Committee. Like the girl in the song from Oklahoma!, he just couldn’t say no.

Embarked in January on a Clayton-backed plan to spend $100 million less than Legislative Budget Board recommendations, but sent to the floor in April a bill spending $414 million more, missing the target by half a billion dollars. In between, completely lost control of his committee. Never made any serious attempt to stop the music while the rest of the committee danced merrily to a pork barrel polka. On one occasion a committee member asked Presnal for permission to inflate his favorite college’s budget and was told, “Why not? Might as well sink the boat all the way.”

Among the committee’s grosser excesses: it jacked up one pork barrel program from $2 million to $20 million, proposed to pay off a junior college’s bank loan, and scattered new public jobs around the state – in committee members’ districts. No one carried away more booty than Presnal himself, who saw that Texas A&M and Bryan got everything possible. The final bill had more blubber than a fat farm; one member of the Clayton team called it “the worst appropriations bill that’s ever been reported.”

Dismayed Clayton by his abdication of responsibility; the House came close to outright rebellion when a move to send the bill back to committee failed by only five votes. The House was then treated to the unprecedented exhibition of the Appropriations Committee chairman leading the assault on his own bill; rarely in politics is so much dirty linen given so public a washing.

When not up to his elbows in pork, was up to his neck in hot water. Sponsored a bill prohibiting a bank from moving from one county to another, even with state banking board permission – an effort to block a Hearne bank from moving to the Bryan area, where Presnal owns stock in a bank. Tried to split the private employment industry’s regulatory board from the Bureau of Labor Standards; the move collapsed following the revelation that Presnal’s brother lobbies for employment agencies.

Not a bad person, but just natural furniture who should never have been expected to be anything else, not even when given the most powerful position in the Legislature. Seldom has mediocrity been so well rewarded since Caligula appointed his horse Consul.

Joe Tom Robbins, 42, Republican, Lubbock. A wire-to-wire worst. Like the comic book character Jow Btfsplk, seemed to attract disaster. Jumped the gun six weeks before the session started by getting arrested in Austin for public drunkenness and impersonating a police officer while celebrating the end of an orientation session for incoming legislators. By the time the Legislature convened, was already written off as a joke; spent the session alone at his desk, avoided assiduously by other legislators as though he were carrying bubonic plague.

Nor did things get any better. The first legislator to be spotted violating the House rules by voting for an absent member; everyone does it, but the hapless Robbins naturally got caught. A local bill implementing one of his major campaign issues proved so unpopular back home that he had to drop it. Another of his bills would have provided mandatory imprisonment for first offenders; had Robbins’ bill passed it could have produced the memorable result of ensnaring the author as one of its first victims.

Continued to bumble his way through the session. Took a firm – and courageous – stand in committee against recalling Texas’ ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment, then tried to mend fences with anti-ERA forces by voting against a pilot program for displaced homemakers; he only made both sides mad. A local bill he carried for Texas Tech had to be lobbied through the committee after the bill’s backers were warned, “Don’t let Robbins testify, he’ll screw it up”; when the bill came up on the local and uncontested calendar, Robbins was nowhere to be seen, and another member had to pass the bill for him.

The two most prevalent comments among other members and lobbyists: “I don’t know him” and “I feel sorry for him.” Overcame long odds to make the Ten Worst list: didn’t even run in the Republican primary, but the winner left town and the loser voted in the Democratic primary, making him ineligible to represent the GOP. The local party had to name someone to face a highly favored Democrat, and some inspiration led them to pick Robbins. What they got was, in the words of one amused lobbyist, “probably the first member in history who was already a lame duck the day he was sworn in.”

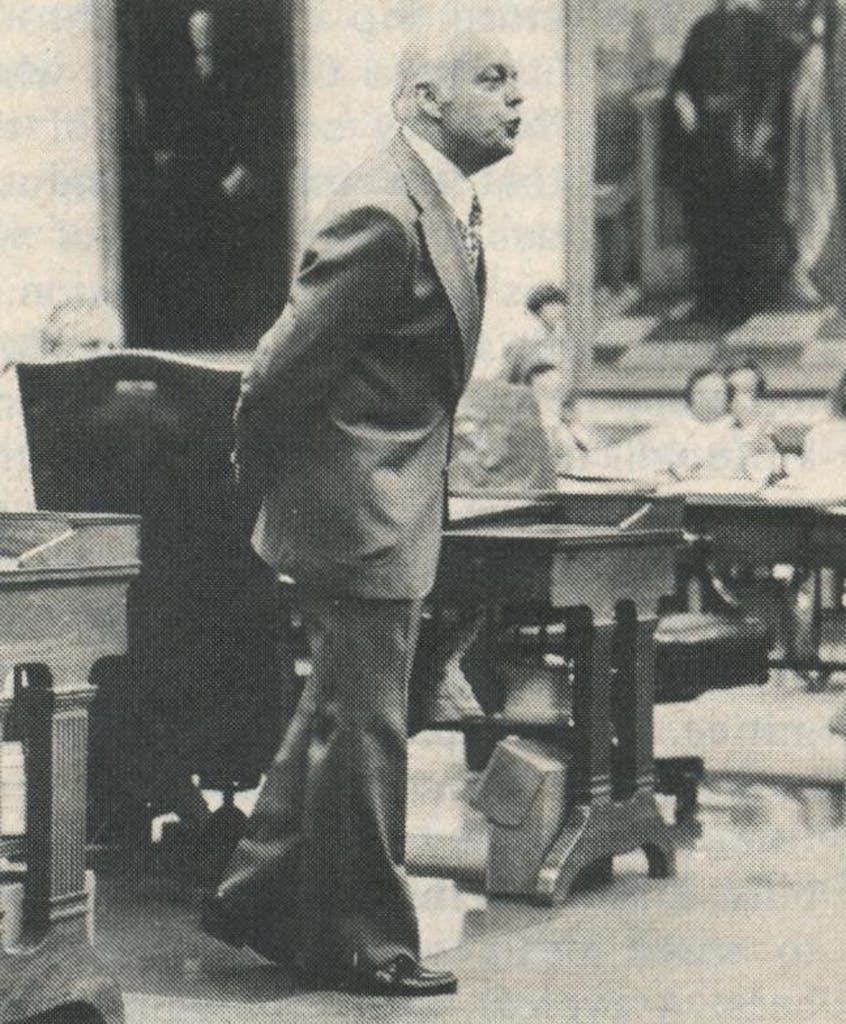

Clay Smothers, 42, conservative Democrat, Dallas. One newspaper described him as a black Archie Bunker; a black Theodore Bilbo would be more accurate. An old-fashioned demagogue who proved that harangues and diatribes know no color boundaries.

On the Ten Worst list not for what he said, but for the way he said it. Represents a legitimate constituency – conservative blacks – who badly need a rational voice in the political arena; Smothers, however, wasn’t it. Never took the microphone expect to prattle about his pet peeves, such as homosexuals and the Equal Rights Amendment (“I am against blacks, Mexicans, women, Indians, and queers talking to me about their rights”).

Betrayed as a demagogue by his failure to do his homework. Trying to rebut arguments that capital punishment discriminates against minorities, claimed that death row was predominantly inhabited by blacks because most murder victims are black – then was embarrassed when someone pointed out that no blacks are on death row for killing other blacks. Before a vote on increasing welfare benefits, took the microphone to denounce welfare cheats – only to be informed that Texas has the lowest rate of welfare fraud in the country. Enrages other blacks not so much by what he says, but by violating legislative courtesy in refusing to yield to their questions.

Strictly a headline seeker and a publicity hound. Lost previous races for the House (1970), Senate (1972), vice president (finished fourth in the 1972 Democratic balloting after nominating himself), Dallas City Council (1973), State Board of Education (1974), and mayor of Caney City (1975): what unlucky star caused the 65th Legislature to be the first political body rewarded with his presence? Smothers’ next goal: lieutenant governor, just to prove that a black can win a state-wide race. Perhaps Texas hasn’t come far enough for Barbara Jordan to break the ice, but surely it has come too far for Clay Smothers.

SPECIAL AWARDS

Bridge Over Troubled Waters

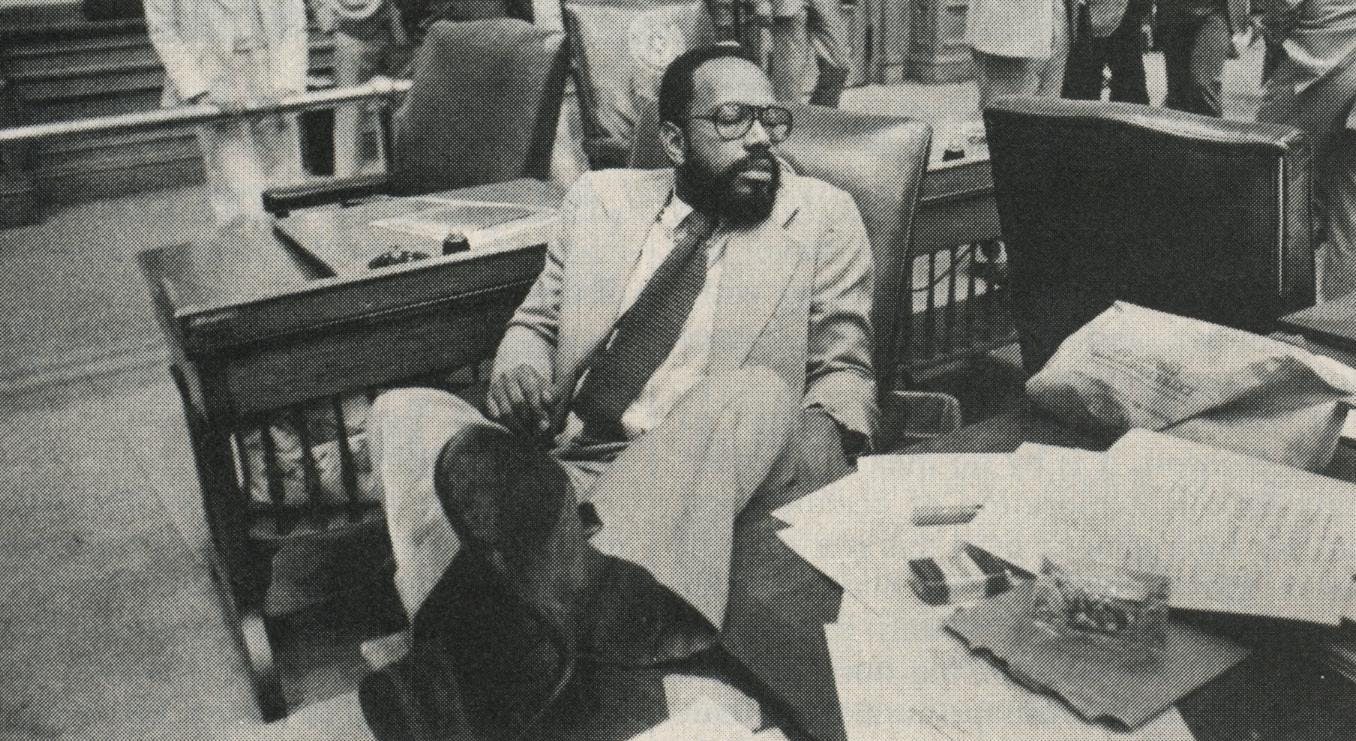

On his first day on the Texas Legislature in 1973, George T. “Mickey” Leland (32, Houston) wore a Tanzanian national dress coat and beads. With his blue eyes, goatee, and red Afro, he prompted many Texas politicians to muse on the apocalypse; it turned out to be closer to the millennium. When, at the close of the 1977 session, Leland addressed his colleagues wearing a three-piece pin-striped suit, he stood before the House as its best-like member – and more important, its conscience. In the course of pragmatically changing his own dress, this former Black Panther ally has enlarged and expanded the political process by bringing the turbulent issues of race and poverty off the streets and into the House chamber.

His style is his strength: he throws verbal barbs at his fellow legislators for what he feels is their indifference to humanitarian issues, then heals the wounds with the balm of humor. Leland misses few opportunities for either passion (which gets him in trouble for being too emotional) or horseplay (which pulls him out before he gets in too deep). If someone needs to speak up for Texans on welfare or to quiet a demagogue with a water pistol, count on Mickey Leland for both.

Like all politicians, he doesn’t always win, but unlike a long line of Texas liberals, white and black, he does win his share – especially on the powerful Appropriations Committee, where he fought successfully for black colleges and the first increase in welfare benefits since 1969. He is a voice in the political process for people who had none, and he uses it without selling out or alienating his conservative colleagues. He has only begun to grow; no one in the House would be harder to replace.

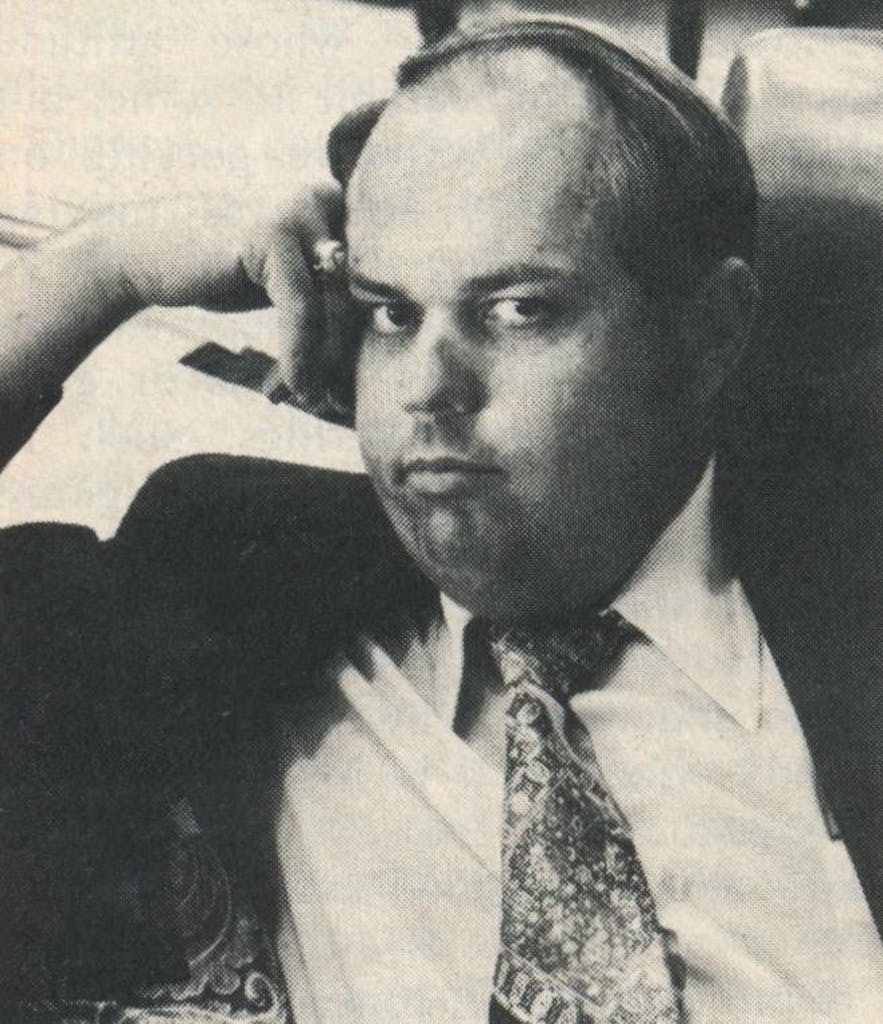

Washington: if he wasn’t great he was bored; if he wasn’t bored he was gone.

Missing In Action

Two of the Legislature’s more able members, both of whom have appeared on previous Ten Best lists, came nowhere close to making the list this time. In fact, for much of the session, they were nowhere close to Austin.

Craig Washington (35, Houston) is an overpoweringly strong, charismatic member – on the rare occasion he is in town. He put on one of the best performances of the session during its last two hours, narrowing Clayton’s procedural options on school finance with a devastating series of parliamentary inquiries. But for much of the session he was nowhere to be seen – unless you happened to look in Houston, where Washington was practicing law. He missed the roll call so frequently that on his return from a long absence he was introduced to the House as “a distinguished former member.”

Sarah Weddington (32, Austin) played hookey with more style. Early in the session she repeatedly “walked” to avoid key votes; later she was out running errands during debate on her own amendment to raise welfare payments to children; finally, when the going got tough in the final two weeks, she opted for a vacation to China. The reaction of her constituents, like the cuisine she was savoring, was hot and sour.

There were also combat casualties most notably 1979 Speaker candidate Buddy Temple (35, Diboll) and his chief lieutenant Luther Jones (30, El Paso). Since Clayton is seeking a third term, both Temple and Jones spent this session as prisoners of war.

Furniture

The term “furniture” first came into use around the Legislature to describe members who, by virtue of their indifference or ineffectualness, were indistinguishable from their desks, chairs, and inkwells. It is now used, casually and more generally, to identify the most inconsequential members.

The Furniture List for the 65th Legislature:

HOUSE

New Furniture:

William Blanton, Carrollton

Betty Denton, Waco

Tom Martin, George West

Pete Patterson, Brookston

Lou Nelle Sutton, San Antonio

Robert Valles, El Paso

Used Furniture:

Jim Clark, Pasadena

Tony Garcia, Pharr

Joe Hernandez, San Antonio

Elmer Martin, Colorado City

Ed Mayes, Granbury

T. H. McDonald, Sr., Mesquite

David Stubbeman, Abilene

Ruben Torres, Brownsville

Leroy Wieting, Portland

Reupholstered Furniture:

Charles Finnell, Holliday

SENATE

Betty Andujar, Fort Worth

Frank Lombardino, San Antonio

Lindon Williams, Houston