DOUGLAS BRINKLEY

President Bush has hopes of being seen as Harry Truman. Truman has become the patron saint of failed presidents, because he left office with a 27 percent approval rating and people were saying, “To err is Truman,” yet look at what he did: the Marshall Plan, the creation of NATO, the Truman Doctrine. The difference is that Harry Truman actually won a war, World War II, while Bush is losing one in Iraq. Bush is like a poker player who bet all his chips on Iraq, and it hasn’t come out the way he wanted.

They’re talking about building his presidential library at Southern Methodist University, and what they should do is say, “Look, after 9/11 he grabbed the bullhorn and said, ‘I’m going to protect America,’ and on his watch America was not attacked again.” The problem is that the bullhorn moment gets obfuscated and loses some of its grit, because the other sound bites that are going to be remembered are “Mission accomplished” and “Wanted: Dead or alive.”

Iraq is going to be known as Mr. Bush’s war. It was a war of choice. Other presidents have had wars of choice. James K. Polk had a war of choice. He decided he wanted the Southwest and declared war on a false pretext. He sent Zachary Taylor over the border to egg on the Mexicans, because Mexico wouldn’t sell modern-day California, New Mexico, and Arizona, and Polk said, “Okay, we’ll go to war.” But Polk is considered a near-great president because he won the Mexican War. William McKinley had a war of choice. In the Spanish-American War, half the country was outraged at him. A group of anti-imperialists, including Mark Twain and William James, were saying this is insane, but McKinley won the war in six months. Both wars were American victories. Bush’s problem is that his war, so far, is a loss. That is one thing Americans won’t stomach. It’s not a matter of there being a false pretext for the war. Polk made a pretext of Mexicans coming across the border. McKinley made a pretext out of the Maine’s being blown up by Spain when it was really an onboard fire. You can have a phony pretext for war, but you’ve got to win. By not winning in Iraq, President Bush has very little legacy to stand on.

There was also a meanness of spirit that started coming out. This was not somebody who was in any way healing the nation or trying to be bipartisan. He became a stubborn ideologue. Stubbornness is a positive quality of presidential leadership—if you’re right about what you’re stubborn about. What he can salvage for a legacy is that after 9/11 America was not attacked, that he won two elections, that he helped bring about a return of the conservative movement, that he had two U.S. Supreme Court nominees confirmed. But he will be judged harshly for his inaction after Hurricane Katrina. For five long days after the storm, he did not visit Louisiana or Mississippi. He did an Air Force One flyover instead of putting boots on the ground. He failed to inspire the nation.

I’m editing Ronald Reagan’s diaries right now for a book. Nancy Reagan gave them to me, and they’re extraordinary. When terrorists blew up the Marine barracks in Lebanon, Reagan was frustrated and furious, as Bush was after 9/11. But he didn’t stick us in a war in the Middle East with no exit.

ROBERT CARO

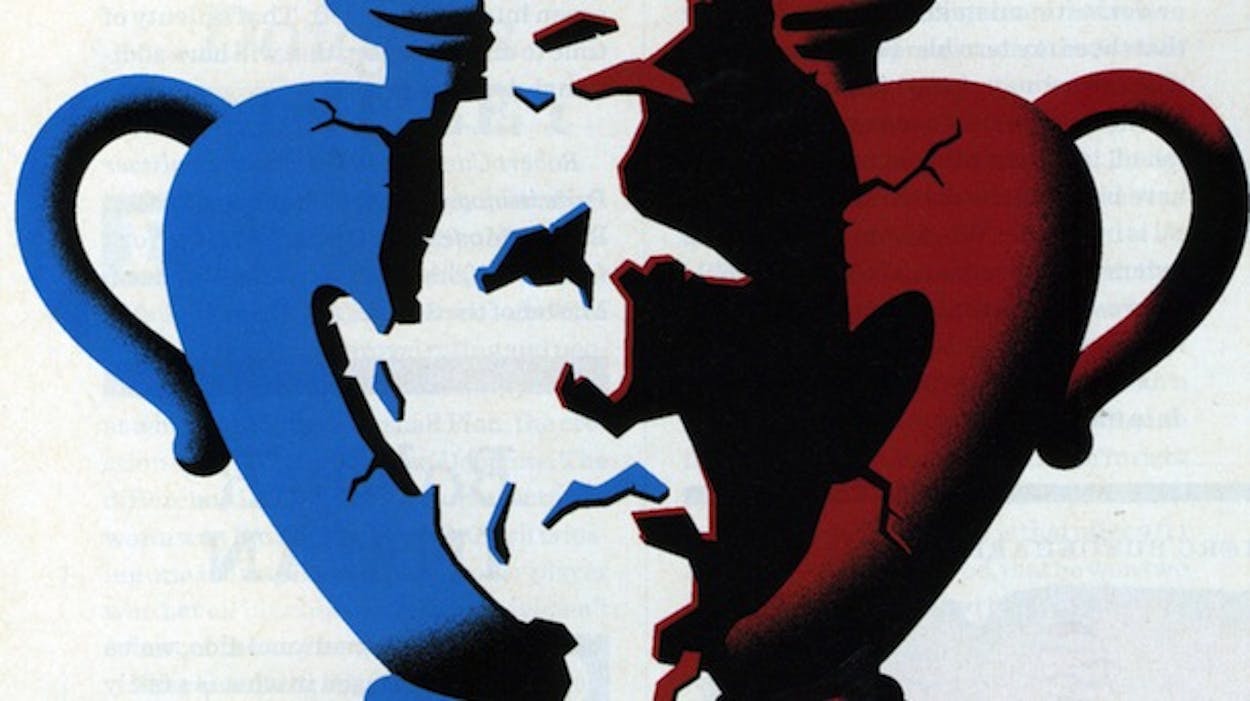

Presidents are very competitive people: All their lives they’ve been running for something. When you get to be president and you’re in your second term, there’s nothing left to run for except your legacy, your place in history. That’s what President Bush is running for now. And in my opinion, at this moment, he’s losing.

I am constantly asked to compare him with Lyndon Johnson. But with Lyndon Johnson the scale has two sides—actually, with Lyndon Johnson, it has probably thirty sides. Certainly on one side you have his mighty domestic achievements: the civil rights acts of 1964 and 1965 and the war on poverty. On the other side you have Vietnam. You have a balance. So far, I do not see any comparable domestic accomplishments in George Bush’s presidency. As of now, Iraq is going to be his legacy. All the weight is on the foreign policy half of the scale.

What I want to say next is something I know may turn out to be wrong, because if there is one thing I’ve learned in doing research on Lyndon Johnson’s presidency, it is that so many things we thought were true at the time turn out, when we finally have the documents and the minutes of meetings to study, to have a different explanation. When future historians are evaluating the Bush presidency, they will certainly have a lot of information that historians do not have today. But, having said that, I am unable as of now to escape the feeling that George Bush has done what is, for a president, a very dangerous thing. He has surrounded himself with people who have the same way of looking at the world as he does. He has surrounded himself with people who tell him only what he wants to hear.

That’s very comforting when you lie awake during the night, but the greatest presidents have been distinguished by a different characteristic: They take care to listen to all sides. John F. Kennedy had a foreign policy disaster with the Bay of Pigs. What he learned from that is, you have to listen to other sides besides the CIA’s and the military’s, and he made sure, in every instance after that, that he did—most notably in the Cuban Missile Crisis. It’s quite dramatic to read the two volumes of transcripts of the tapes of the deliberations in Kennedy’s Cabinet Room about the Cuban Missile Crisis. You think, “This is a president you can disagree with. He doesn’t try to intimidate you. He encourages you to give your point of view, even if it’s directly opposed to his point of view.” That was also the thing about Franklin Roosevelt. George Bush says, “I’m the decider.” Well, Roosevelt was the decider too. But he insisted upon hearing all the sides. You get the feeling that President Bush is convinced he’s right without listening to the other side.

I’m writing about Lyndon Johnson’s presidency forty years later. It’s just striking to me how events we thought were so important at the time I’m only going to give a couple of pages to. So when people talk about George Bush’s war on science or domestic mistakes—I don’t disagree that those are terrible. But in forty years, when someone writes a history of his presidency, their significance will be diminished, in my opinion, because they will have been reversed. I think such a reversal is inevitable. What I don’t think will be reversed—at least not in any foreseeable future—are the forces he’s unleashed by invading Iraq.

Is there anything that the president can do in the next two years to alter his legacy? Absolutely. Kennedy’s entire presidency wasn’t quite three years. Bush has about seven hundred days left. That’s plenty of time to create a legacy that will have additional elements to it.

BOBBY R. INMAN

On the international side, we’ve been engaged in what is a fairly unique experiment in the post—World War II world: the U.S. going it alone, as opposed to building alliances, stitching them together, getting people to go with us in whatever adventures we are going to undertake. I don’t think this president had a strong view about that process, either its history or its value, so he was to some degree a blank sheet of paper, an open book—whatever kind way one can phrase it. But he brought into the administration, with the selection of the vice president, a group of very articulate people who believed strongly that the U.S. was the only superpower, that we should use our power, that we should not be constrained in using our power by the views of others—by the U.N., by other countries. And if somebody—a Tony Blair—wanted to get aligned with us, it would be wonderful to have them, but we weren’t awfully deferential. NATO has survived; it’s still there, active in Afghanistan, so it’s hard to make an evaluation that this approach has been destructive to existing alliances. U.S.-Japan seems to be as strong as or stronger than it’s ever been. It’s in the U.N. arena, and in the arena of those who are not closely knit with us, that the damage has been pretty severe—where people who have gotten accustomed to at least having their views solicited are offended, angry, critical, disillusioned.

If, in fact, over these next two years we see that the president has learned that a lot of the advice he got was very bad and ends up making a major effort to strengthen existing alliances, to rebuild relationships, and to get us back on a keel where we’re leading and getting the world to join us instead of trying to tell everyone what to do, then it’s not long-term damage. But it’s a setback in terms of what might have been accomplished.

On the domestic side, efforts to improve the quality of education may not have all been effective, but the country needs to be much more competitive in what we’re producing. Whatever one thinks of tax cuts, they got us out of a pretty deep recession and touched off another period of growth that’s lasted longer than most people I listen to had projected it would. On Social Security, it’s possible to deal with the problem; if, instead of grand schemes that they didn’t have either the capacity or the focus to sell to the public, they’d simply upped the retirement age to 66, then 67, then 68, they would have solved it.

If, in other words, he confronts the reality of dealing with a Congress that looks a little like the Texas Legislature of earlier years, narrows the expectations, sets some common, useful goals, and gets them enacted, it will give historians a different context. If he doesn’t, his will not be viewed as a successful presidency.

MATTHEW DOWD

In the short term, historians will say George W. Bush missed some real opportunities in the aftermath of 9/11 to call the country to some shared sacrifice, to be a unifier, to bring people together and reestablish community. There were hopeful signs at the beginning—bipartisan education reform, the first round of tax cuts—but it all got swallowed up by Iraq, which took over his presidency. I think he’ll be judged on some things he did on 9/11 that were good: his emotional connection to the country, his sturdiness and compassion. The problem is that his gut-level bond with the American public has been seriously damaged and may be lost.

Another disappointment is that his promise to reform government in a fundamental way never fully happened. He was going to appoint new people who would remake government in a way that fit the twenty-first century. In this respect, I think the president suffered from his success in the 2002 midterms. As most of us know—and it’s why I switched parties and went to work for him—he was best at what he did in Texas, which was working with Democrats like Bob Bullock and Pete Laney. The biggest hope and aspiration of those of us who were brought in as former Democrats was that we could make Washington into a place, like Texas, where people could sit down, have a conversation, socialize, not judge one another as good or evil, not question intentions, and actually get things done. But when all the levers of power in Washington became Republican, creating consensus seemed to become unnecessary at the White House. That hurt him. Now, near the end of his presidency, when many of us thought we would have helped solve the problem of polarization, we’re in an even more polarized place.

How does he reestablish that gut connection he had with the American public? You can’t do it through sales and marketing. This is a substantive problem that requires a substantive change. First, a tremendous sense of compromise and consensus building—even if he has to sacrifice some of his principles along the way. Second, a resolution on Iraq that represents a significant shift in policy. Once you’ve lost the support of the public on the war, which is where we are today, sending in a small contingent of troops is likely going to be seen as not helpful. He’d be much better off with the public if he said, “This is a mess, we made mistakes, and the only way to fix it is a wholesale change.” And that could mean either a serious increase in troop strength or withdrawal.

KATHLEEN HALL JAMIESON

From my perspective, I think that George Bush’s legacy is going to be his use of signing statements [written documents that presidents can issue when they sign a bill into law]. He has used them to replace the veto, which represents a shift in institutional power and alters the relationship between the branches. When a president doesn’t issue a veto until the sixth year of his presidency but nonetheless systematically takes exception to legislation, that person is doing something different from what his predecessors did. Some observers view this as a healthy exercise of executive power; others view it as overstepping. I’m in the second camp.

Many signing statements are absolutely benign. They applaud Congress for passing the legislation, for instance. It’s true that earlier presidents used signing statements as something akin to what I call a “de facto item veto.” What’s new in this president’s use is the displacement of the traditional veto for this alternative form. A good example is John McCain’s proposal from 2005 that banned the torture of detainees and passed with a veto-proof majority. Bush had already made clear his administration’s views on the matter, but he held a press availability with Senator McCain in which he said positive things about the legislation. He engaged in what I would call “public embrace, private repudiation.” Two weeks after the press conference, President Bush signed the bill, and the signing statement was posted on the White House Web site. Its eighth paragraph reserved the right to nullify the provision over which McCain and Bush had fought. The president didn’t say he would nullify it; he said he reserved the right to do so. That happened on December 30. Where do you think reporters are on December 30? They’re not paying attention to the White House Web site.

So you can ask if the press availability was real. Now you have a de facto item veto in a constitutionally problematic moment, because had Bush simply vetoed the bill, McCain would have had the votes to override it. That would have checked the president, as provided for in the Constitution.

I think we will look back at this administration’s decisions in fifty years the way we look at Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus. The signing statement is an assertion of presidential prerogative, and what makes it so intriguing is that it is largely an unaccountable power.

We don’t know when the war on terror is going to end. It could be like the Cold War; it could last a long time. If President Bush’s successors continue to do this, it could be not simply an important legacy. It could be the most important legacy. It shifts your presumption of what presidents can do.

ROBERT DALLEK

The war in Iraq is obviously going to be a huge part of George W. Bush’s presidential performance, and because it is going so poorly, it’s bound to have negative repercussions on his standing. Another thing that will hurt him is Hurricane Katrina and his administration’s handling of that. Historians will point to the fact that Bush was, in some respects, a small-government president, someone who didn’t believe in using government the way Lyndon Johnson did. Johnson had a huge investment in the idea that government was not the problem, it was the solution. Whatever the motives were for the reaction to Katrina or whatever we find years down the road that reveal the inner workings of the administration’s response, it’s going to work against him.

What’s interesting with Bush is how he believes he’ll be viewed by historians. When asked about his legacy, he says it’s too soon to tell, that we’ll have to wait thirty, forty, fifty years. And he points to Truman. Bush is banking on the fact that he’ll get credit for putting in place the strategy for winning this larger war against terrorists even if Iraq looks like a stumbling affair at the end of his term, in January 2009.

But there’s a big difference between Truman and Bush. Truman, with George Kennan’s help, was the architect of the containment doctrine, which later presidents followed. Truman makes a comeback because he put in place the long-term strategy that won the Cold War. What I think historians will ask is, “What is Bush’s strategy?” There isn’t a containment strategy. The only thing you can point to is preemption: Strike at them before they strike at us. That, at this moment, is a failure.

If you look to the domestic side, he hasn’t done anything that stands out as a landmark achievement, the way the Civil Rights Act of 1964 or the Voting Rights Act of 1965 does. Bush passed No Child Left Behind, but that seems to have faded into the woodwork. Though the economy is decent, presidents don’t get a lot of credit for presiding over a solid economy. They can get a lot of demerits for a weak economy but not much praise for a strong economy. The other major initiative is Medicare reform, and the Democrats are going to go after that now by trying to force the drug companies to negotiate with the government over prices. Then there’s the question of the environment. As we receive more information about global warming, I believe there will be criticism for the administration’s rejection of the Kyoto treaty. It has been one thing after another.

As for his leadership, Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney have tried very hard to exert the power of the executive. Cheney has been outspoken about the fact that Watergate and actions that Congress took in its aftermath have reined in the president too much. They obviously made a concerted effort to reassert presidential authority, but in many respects it has backfired. It has raised too many issues about civil liberties. Bush may ultimately receive credit for preventing another 9/11-style attack in the United States by unleashing the FBI, the CIA, and the NSA, but those records will remain hidden for a long time.

So, will Bush be in the top rank among presidents? Obviously not. Will he be seen as an average president? Possibly not. The fact that he won a second term is a feather in his cap because there have been only sixteen presidents who carried that off. It’s pretty rare company, but that’s not going to shield him from negative assessments.

MARK MCKINNON

It is almost impossible to reflect upon what a president’s legacy will be until long after his presidency is over. If you look back at other presidents, you can see how we would have made great mistakes about their legacies had we made those decisions at the time. We would have thought LBJ’s legacy was all about Vietnam and not the Great Society. If we were having this discussion about Reagan six years into his presidency, we would think his legacy would be Iran-contra. History is shaped by the context that both precedes and follows a presidency. That said, we can make some observations that may reflect what will happen in the future.

One legacy will be that George W. Bush was a consequential president. This is interesting, because going into his presidency, certainly his critics and even some of his supporters were not likely to think that about him. This president determined that he had no interest in warming the seat of the presidency and said as much—and he clearly has not done so. I think he will be seen as a president of great consequence, and history will judge how great those consequences were.

The obvious question—where does Iraq figure in the legacy?—is one that we won’t know the answer to for maybe twenty years. Even if we have what could be described as some sort of resolution sometime soon, I don’t think that there’s going to be a complete resolution, and I don’t think that “sometime soon” is going to be sometime soon. We may make progress in Iraq, but it could be decades before we really understand what’s going to happen in that part of the world. As historians look back, a lot of that will be laid at the feet of George W. Bush, for better or for worse.

Of course, Iraq throws a shadow over a lot of the other important contributions of George Bush’s that might otherwise have gotten a lot more attention—like education reform. He has radically transformed the federal government’s role in education, which is very unlike a Republican. That’s what initially drew me to him—the sorts of things that he was doing in Texas at a time when Republican rhetoric was dominated by people whose approach to government was to burn it down. George Bush, unlike other Republicans at the time, recognized that there was a role for limited government. Education reform and aid to Africa to fight AIDS reflect the idea of compassionate conservatism as it started in Texas. The president has more than tripled aid to Africa for AIDS, and longtime activists on this issue, like Bono, give him credit for doing more than anyone else. I remember [former presidential speechwriter] Mike Gerson saying to the president, “Can we really afford to do this?” and the president saying, “We really can’t afford not to.” This is another thing contrary to what you might expect from a Republican president.

There’s a lot of debate in Washington about the partisan activity that we’ve seen on both sides of the aisle. Tony Blankley [of the Washington Times] says we’ll see bipartisanship in Washington when we see unicorns at the Capitol, but we saw unicorns here in Texas. His critics see the president as ideological, but my view is that he is pragmatic. He saw he had a majority, and he was driven by getting things done. I believe that he looks at the next couple of years pragmatically, and I think we will see him adapt and evolve. There are opportunities here—for reauthorization of No Child Left Behind, for immigration reform, for new directions in energy policy—and here we may see some interesting ideas from the president.

Finally—and knock on wood—I remember well the terrifying time of 9/11 and how, in the weeks and months afterward, we were pretty sure life in America would be like living in Israel and that there would be suicide bombers on the streets of New York. We haven’t had another attack, and God willing, we won’t for some time. Critics can argue, but the facts are the facts: The president has protected the homeland.

MICHAEL LIND

If you look at George W. Bush in a larger perspective quite apart from Iraq, you see him as the peak of the post-sixties conservative wave that began with the white backlash against the civil rights revolution. A lot of conservative white Southern and Northern ethnic Democrats who were alienated by racial and cultural liberalism broke away and created, first, a Republican presidential majority and, then, a Republican congressional majority. And yet under Bush, every major conservative proposal of the past thirty or forty years has died—with the exception of tax cuts—because these Reagan Democrats are actually Roosevelt Democrats: They actually like the New Deal. They like the Great Society. They have nothing against Social Security. They want their Medicare. The Republican Congress, in Bush’s first term, passed the Medicare drug benefit, so he presided over the biggest expansion of socialism in the United States since LBJ.

But wartime presidents are remembered for their wars and whether the wars were successful or disastrous. I think it’s hard to see Bush’s Iraq war turning into a success. It’s clear that Saddam Hussein was the enemy of Al Qaeda; Saddam’s regime was one of the regimes that Osama bin Laden and the other jihadists wanted to overthrow in favor of a Muslim theocracy. Ironically, we’ve replaced his secular dictatorship with what appears to be a clerical-dominated Shia regime. So the whole thing backfired if the goal was to keep Islamists out of power.

Construing Iraq as part of the war on terror will be seen, in retrospect, as an attempt to link two completely unrelated things: the campaign against Al Qaeda and the jihadists and the desire to remove Saddam Hussein in order to have permanent military bases in Iraq. The strategic goal of installing a pro-American regime was essentially driven by the desire to consolidate the post—Gulf War hegemony of the United States in the Persian Gulf, which the U.S. had previously contested with the Soviets and which had been primarily a British and a French sphere of influence up until the fifties and sixties. Part of the basis of American power after the Cold War and the Gulf War was the ability of the U.S. to protect and/or threaten the oil of other industrial nations, including not only Europe but also China, India, and Japan. In order to do that, it’s helpful to have bases in the region, and it was thought that if you installed a pro-American government in Iraq, then you would have a sort of South Korea-type base from which you could intimidate Syria and Iran and other enemy regimes in the region. The people of Iraq, it was thought, being secular and hopefully liberal and democratic, would not wage a holy war against our forces on their soil.

That was the plan. It was a fine strategic plan. It just was based on a gratuitous ignorance of the country, because the hawks of the Bush administration deliberately ignored the people who actually knew the region—mainly State Department folks—because they considered them “Arabists” or appeasers of Arab regimes.

The Iraq war will be seen as a “one-off” war, like McKinley’s Spanish-American War. It’s kind of isolated, a blip in American history that doesn’t really go anywhere. In other words, Iraq won’t be like Vietnam or Korea, which were episodes in the Cold War. That’s the one thing Bush will be remembered for: an unnecessary war of choice that turned into a disaster.

If Bush were to attack Iran in the next two years, he could cement his legacy as the worst commander in chief of all time. The Iranians hate the Sunni jihadists and Al Qaeda hates both the Iranians and the Iraqi Baathists. To declare war simultaneously on three archenemies who are not coordinated, who have not formed an alliance against you, is just madness.

He could also make his legacy worse by means of the troop surge, because it’s being done over the opposition of many of his generals and for purely political reasons, in order to protect himself from the accusation that we would have won if he had done more. If this leads to the deaths of hundreds or thousands more American troops, merely to cover his behind politically at home, the judgment of history will be even harsher.

PAUL BEGALA

My first test is an empirical one: Did George W. Bush accomplish what he set out to accomplish? Look at Ronald Reagan. Ronald Reagan accomplished almost all of the big things he set out to do. He didn’t shrink the size of government, which was a problem, but other than that, he cut taxes, he certainly restored our faith in ourselves, he built up the military, he confronted the Soviet Union, and he tried to reduce the number of nuclear weapons. He was a successful president by that standard. Bill Clinton, with the glaring omission of passing a national health care plan, accomplished everything he set out to do. He promised to cut the deficit in half, and he eliminated it completely. He promised to end welfare as we know it, and ten years later it looks like it’s very successful.

By that measure, Mr. Bush has been an abject failure. He promised to be a uniter, not a divider. You can look at data that show him to be even more divisive than Richard Nixon—he’s the most divisive president of the past fifty years. He clearly has not conducted a humble foreign policy, which is what he promised. He clearly has not shied away from nation building, which he said would be terrible for America. In every single State of the Union address, he promised to give us energy independence, but he’s done nothing to do it. He promised to cut taxes, and he did, but he promised the cuts would primarily benefit the middle class, which is not true. People who make more than $1 million a year got far, far more than anybody else. And he promised to “restore honor and dignity to the Oval Office,” yet he used that office to spread falsehoods and fabrications that buffaloed our nation into war. To send young heroes to their death by deliberate prevarication is the worst thing a president can do. “Honor and dignity” indeed.

Another test is, How long do your benefits last, and how long does it take to clean up your mistakes? By that standard, he’s the worst president in history. The benefits of his tax cuts are evanescent; they come and go. They’re supposed to expire in three years or four years, and it’s very unlikely that they’ll be continued, because we can’t afford them. No Child Left Behind? Heart in the right place, but several years into it, many educators think it hasn’t worked out. Now look at the burdens. People in the Middle East are killing one another over disputes that go back fourteen centuries. They’re going to hold a grudge against us for a while. We are going to be handicapped in the Muslim world for generations because of what Mr. Bush did. Add to that the heartbreak of all the families whose sons are dead or wounded.

My fourteen-year-old son did a report on Johnson last year, and he came away a great admirer of LBJ’s because of the civil rights movement. He didn’t even get into the Great Society, creating Medicare and Medicaid, expanding student aid—these things last and last, and they balance out against the god-awful war. What does President Bush have to balance against his god-awful war? Nothing.

NIALL FERGUSON

Historical reputations have a tendency to go through a dip and then a recovery. We’re going to have a dip in President Bush’s reputation—we’re in it already, and I suspect it may well persist—but ten years from now, there’ll almost certainly be a revisionist book, and it will probably say two things. First, that the economic record of the Bush administration was actually very successful. The aftermath of the stock market crash could have been much more severe; the tax cuts worked, despite their counterintuitively being targeted at the relatively rich; and the growth of the economy consistently surprised, not to say disappointed, the Cassandras. It’s been a remarkable showing, really, and some of the credit should go to the president. Second, that another president, perhaps a President Gore, would not have responded with such courage and conviction to 9/11 and that Bush was right to go after Al Qaeda in Afghanistan. The war on terror was not a fabrication. There is good reason to hypothesize that other attacks were successfully thwarted by the escalation of homeland security. I don’t think it’s because Al Qaeda stopped wanting to blow up American cities.

Now, even the most enthusiastic revisionist is going to then say “but,” and “but” will be the beginning of the Iraq chapter. The thing about Iraq is not that it was fundamentally wrong to do but that its execution was bungled, really at two key moments. One was in the immediate aftermath of the occupation, when a larger force could have preserved order. The other was in 2004, when Muqtada al-Sadr and the insurgents in Fallujah could have been taken out. On both those occasions, the president probably yielded to the judgment of others rather than to his own gut instinct. Nobody would claim that he had a great knowledge of the Middle East when he came into office. He’s a man with tremendously good political instincts, but he was always going to be reliant on sound advice if foreign policy became his number one preoccupation, which on 9/11 it did.

He did have an important insight in the wake of the attacks, though: that radical Islamic organizations like Al Qaeda depend on governments for their backing. The problem was that after Afghanistan, most of these governments were American allies. So Bush didn’t have an awful lot of targets that were as easy to take out, and we have to say that the advice he got on Iraq, that it was the logical next step, was very flawed.

At this point it’s hard to imagine a happy ending in Iraq. Odds are on a protracted civil war, and though it would be nice to think of this as the Iraqi version of the American Civil War, I’m afraid it’s more like a central African civil war. The historical experience is that when poor, multiethnic societies get involved in this kind of conflict, it’s hard to stop. They develop a self-perpetuating momentum. This is the great unintended consequence. But it must be said that there was evidence on the side of caution that was ignored, and perhaps the president’s strength in so many other situations—his decisiveness, his gut instinct—turned out in a rather tragic way to be his weakness.

Bush is a risk taker, and we all know that risk takers will sooner or later bet the house on a bad hand. Kennedy was another risk taker, though on some of his mistakes he was never really judged. If you project the Kennedy presidency forward, the Vietnam quagmire would have been on his watch. He really initiated the escalation, and out of motives rather similar to Bush’s. The interesting thing about Bush as a Republican is how often after 9/11 he sounded like a Democrat talking about, well, not quite bearing every burden in the cause of freedom, but close. The other figure who comes to mind is Reagan, who was a risk taker in the Cold War. But Reagan was also lucky; he was prepared to push the Soviets and then yield an enormous amount in the negotiations with Gorbachev, and on both these gambles he won. So Bush belongs in that grouping of presidents, not among the outright failures, the Jimmy Carters, to say nothing of the great economic failures, like Hoover. Bush had the same commitment to the American notion of freedom that Kennedy and Reagan brought to the Cold War. It just turned out that the war on terror was a more ambiguous war.

But it is deeply ironic that we should end up judging George W. Bush above all by his foreign policy, when, as a presidential candidate, he argued cogently that the United States should limit its overseas commitments and focus on domestic issues. September 11 changed the entire character of his presidency. It seemed initially that it would bring out the greatness of Bush, but because there was a fundamental wrong turn taken, it’s going to be very hard, even for my imaginary revisionist historian, to conclude that this was a great presidency. In the end, it’s one of those tantalizing stories of greatness in some measure spoiled by one bad call.

ELSPETH ROSTOW

We’re deep in the age of what one scholar calls “intermesticity.” This is the twinning of the domestic and foreign agendas so closely that you can’t make a significant impact on one side without having a comparable impact on the other. George Bush is caught in this age of intermestics. He has moved in the direction of making a successful outcome in Iraq, his mantra, as an illustration that in that part of the world it is possible to achieve freedom and liberty. He is now in the stage when his legacy will include, quite possibly, Iraq as an example for the neighborhood, yes, but also as a seedbed for intransigence, insurgency, terrorism—precisely the opposite of what he’d hoped. The story is not over yet; we don’t know how the surge will play out. We don’t know whether Bush will be able to buy time between now and the election next year.

Irrespective of what happens between now and the end of his term, what Bush will leave as his legacy is a diminution of support for the United States abroad. This is not measured just in the decline of the U.N., it’s not measured just in the number of countries that have distanced themselves from the hegemonic position of the U.S., but it’s measured by the change in international attitudes toward the United States immediately in the aftermath of 9/11 and by the sour mood of 2007. This is a real cost, because support is going to be of the essence to Bush’s hope that the United States model is the one that will be replicated in the Middle East. I see very few countries that are anxious to follow in Bush’s footsteps. The costs of Bush’s policies are obvious: the blood and treasure being expended in Iraq, the reduction of collective security as a concept, the alienation of former allies, as well as the possibility of a permanent hostility between Muslim and Judeo-Christian worlds. There are other aspects, in terms of energy and oil dependency, that have not been given attention by the Bush administration. All of this is at a cost that can be measured in dollars but can also be measured in historical trends, and these are not going favorably for the Bush administration.

Because of this notion of intermesticity, so much attention and coin of the realm have been dedicated to Iraq that we have impoverished our domestic programs. Think of global warming. Think of environmental decisions that have been counter to at least a significant part of the thinking of the scientific and public policy communities. There’s a range of activities that has detached us from international agreements and from working in the international context with deliberation as opposed to hegemony and unilateralism. All of this is a matter of record, and I would classify it as part of the conventional wisdom.

The first thing I would do, if I were advising Bush, is say that it is not too late to reverse some aspects of the neglected domestic agenda. I’d isolate a few things, as he did when he was governor, and stick to them. I’d think of some overarching cliché—for example, the “New Community”—and give it three elements: education, health care, and the environment. He should call for a series of national meetings and bring together the best minds in the country to improve education from kindergarten through higher education and to revive research. Do the same thing for health care. Call for a national town meeting. See what we can do on the issues of cost and access. In other words, direct the nation’s attention away from its obsession with Iraq and talk about something new and promising in which he will be the leader—a leader who can listen as well as talk, who is willing to be experimental and flexible in contrast to the rigidity of the Bush administration so far.

H. W. BRANDS

What George W. Bush has done is institutionalize unbalanced budgets. He inherited the most favorable budget condition of any president probably since Andrew Jackson. The budget was in surplus, and there was an opportunity to address the two issues that have been hanging over the heads of American administrations for the past thirty years—namely, what do we do about health care and Social Security? Bush has not only kicked those two issues down the road, he’s made them much larger by cutting taxes, and at a time when there was no pressure whatsoever to cut taxes. But he had an ideologically driven insistence that taxes must be cut regardless of the consequences. Well, what has happened is the budget has spun out of balance. It’s going to take decades to bring it back, and as long as it’s so far out of balance, there’s going to be almost no hope of dealing with these legacy issues. And this at the time when baby boomers are starting to retire, when the strain on those two systems is going to be greater than it’s ever been.

Just as cutting taxes was a decision that didn’t have to be made, the same can be said of his foreign policy: There was no groundswell of demand for a war against Iraq. Sure, there was all sorts of support for a war on terror, and a lot of people thought there was a logical connection between the attack of 9/11 and an attempt to clean the Taliban and Al Qaeda out of Afghanistan, but there was no grassroots support in the United States, no large political opinion, pushing him to go to war against Iraq. It was something he decided to do on his own, an utterly elective war. And it’s going to take a long time to undo the negative consequences. A lot of presidents when they come into office are faced with decisions that they have to make. These were two decisions that Bush didn’t have to make at all. And I happen to think in both cases he got it wrong.

I don’t know if the situation in Iraq is salvageable. I’m one who believes that there was a reason that Saddam Hussein ran Iraq as long as he did. Iraqi society was so unstable because Iraq itself is this fiction of a country; there’s no coherence. The only thing that held it together was the strongman at the helm. So maybe the administration will come up with somebody who’s not quite the thug that Saddam was but nonetheless is able to impose a measure of order. Maybe it can get what in Vietnam was called the decent interval, a time where we can pull out and allow six months, eighteen months, two years to lapse before the sky falls in. Then you can more credibly blame it on the Iraqis than on the United States.

Those people who want to say that George W. Bush is the worst president in history have to deal with the comparison to James Buchanan, the president at the time of secession, the one who essentially let the South leave, but I think that in certain respects, if one doesn’t like Bush’s policies, Bush is more culpable than Buchanan. Buchanan didn’t bring secession on. He may have made mistakes in dealing with it, but it wasn’t as though he chose to make this thing happen. I think that’s going to be the biggest criticism of George W. Bush: The things that he chose to have happen—cutting taxes and going to war in Iraq—were not decisions he had to make at all. He decided to do these things utterly on his own. The fact that he got them both wrong is going to really tell against his historical reputation.

DONALD L. EVANS

People’s perceptions today are not necessarily what they’ll be years from now. Historians will see the president’s achievements more clearly in the future. When they look at what this president has been all about—what dramatically, in the early days of his presidency, changed the course of the world—they’ll see that he has done extraordinarily well at protecting America and extraordinarily well at planting the seeds of democracy and freedom in the Middle East and beyond.

I think he’ll get great credit for understanding the challenge that America all of a sudden faced after 9/11. Yes, terrorism was out there and people knew about it and they knew about Osama bin Laden. But it wasn’t until our country was attacked on its own soil that we recognized the seriousness of it, that it would require not just a U.S. response but a global response. He quickly realized that it was a defining moment and understood the responsibility that he had as a leader, that America had as a leader, to take the battle to the terrorists—to begin, in earnest, the war against terrorism. It begins with the security of America. We haven’t, knock on wood, been attacked since 9/11, but not for lack of effort by our enemies. They’re still out there. Their desire is to attack America, to take us down. The president understands that. And to a great degree, that has shaped his presidency.

He has two big responsibilities: the national security of America and the economic security of America. You can’t have one without the other. You can’t have a strong national security posture without being strong economically. And so I think he’ll also get great credit for some of the bold steps he’s taken on the economic side not only to strengthen our domestic economy in this challenging time but, quite frankly, to help lead the global economy. He’s done so through more economic engagement with countries around the world in this whole area of free trade and open trade; he’s signed more free-trade agreements than any previous president. History will look at this guy and say, “He’s somebody who really had a place in his heart for the individual who needed a helping hand, not just in the United States but in the world.” He understands that the biggest problem we have in the world, other than providing democracy and freedom and peace, is poverty, and you cannot take on the big challenge of poverty effectively without the global economy growing at its full potential. And the global economy can’t grow at its full potential without global security. These things are all related.

When they look back, they’ll say, “Whoa!” He was very bold on the tax cuts. He went against many on the other side who said, “You’re going to destroy the economy. You’re going to drive deficits through the roof. Interest rates are going to go straight up.” Just the opposite has happened: a more robust economy, a higher growth rate, more jobs, lower interest rates, greater wealth, more home ownership. We maintained ourselves as the strongest, most dominant economy in the world by far, and that allows us to have this leadership position in the world, which we have the responsibility to use with humility.

Has the president suffered setbacks? Yes. Have there been problems? Sure. But despite all the horrible pictures we see on TV and the heartache and the pain and the suffering, which is terrible and gut-wrenching, I think we’ll step back from this moment. While I know a lot of people think his legacy rests on what happens with Iraq, historians will say, with time and reflection, that he did a remarkable job. He didn’t worry about polls or focus groups or even elections. He worried about doing what was right—and our world will be a better place because of it.

MARVIN OLASKY

For most churchgoing Americans, helping the poor is a crucial moral issue. There’s a lot more in the Bible about helping widows, orphans, and aliens than about anything else except loving God himself. The conservative response to that biblical imperative has been divided. Churchgoers give their money and time to fighting poverty, but then there are the social Darwinists, who sneer at poverty fighting. Others see “compassion” as a word seized by liberals and want to relinquish all claim to it.

What George W. Bush tried to convey is that such relinquishing is wrong both morally and politically. Give up compassion and we give up a piece of what’s best in us. Republicans become the party of corporate suits, of mean-spirited purple people eaters. W. knew that most Americans want an alternative to the failed idea that we measure our concern for the poor by the size of government appropriations rather than the content of our character. The central impulse of compassionate conservatism that he enunciated was that individuals can do a lot more to help their neighbors and that religious groups are particularly good at, as we like to say, “challenges personal and spiritual.” Compassionate conservatism, as it was presented to Governor Bush and embraced by him, meant that smaller government and less government spending led to more help for the poor.

Somehow, that combination of less and more was lost in the shuffle of Washington over the past six years. Some good things happened. The administration promulgated some executive orders that have temporarily removed some discrimination against religious groups. But those small accomplishments fell far short of the original hope for a tough-minded approach that would help the poor while shrinking welfare spending and that would create for years to come a level playing field for all groups involved in helping the poor, whether religious or not. While we got compassionate conservatism on the board, it became distorted. It came to be looked upon as either a political gambit by Republicans trying to buy minority votes or a rhetorical device hoping to fool soccer moms. And so Bush, in this area, has been moderately weak.

He could be stronger by pushing, as he hasn’t done until now, for two of the original proposals of compassionate conservatism. One was a $500 tax credit for any individual who gave that amount to the poverty-fighting nonprofit of his choice. That’s $500 more going to community nonprofits and $500 less going to the Beltway bureaucracy. A second proposal involved vouchers. The idea was that instead of having the Department of Health and Human Services decide which organizations would get grants, needy Americans could vote with their feet and choose groups that dealt most effectively with their problems.

Another thing the president could do is push through a reexamination of disaster policy—a realistic appraisal of what worked and what didn’t work following Hurricane Katrina—so we can do better next time there’s a major disaster. Church workers were the first volunteers on the ground at a time when FEMA was out to lunch. Michael Brown, the famous “Brownie,” was following the governmental playbook by telling emergency responders to stay home unless they had a specific request from governmental authorities. We should try to rebuild from the bottom up, by relying upon community groups and religious groups of all kinds, rather than FEMA and other governmental agencies. They’re largely ruled by paperocracy, often out of fear of litigation, and by bureaucratic habits. Religious groups tend to be a lot more versatile and a lot more responsive.

If W. pushes for decentralization of social services and disaster relief, he can still build a lasting legacy.

BRUCE BARTLETT

There isn’t much question that George W. Bush will rank among the bottom of all presidents in terms of his accomplishments in office. Among Republican presidents, Herbert Hoover has to rank as the worst because his economic policies brought on the Great Depression. The second worst is probably Richard Nixon, but this president is getting pretty close to that. The war is the key element in making this determination.

In my view, one has to look at the necessity of a war, how it was conducted, how many American lives were lost in the process, and its success in terms of achieving the goals of the conflict. The Spanish-American War, for example, was probably unjustified but at least achieved what it was designed to achieve. This war was neither justified nor is it achieving its goals. This could change depending on what happens in the next two years. However, the evidence suggests that rather than try to fix some of the problems that Bush has created, he’s simply going to double his bet in hopes that he can somehow salvage something. I don’t think that’s going to work. People do win the lottery occasionally, but it’s not a good strategy for enriching yourself.

As for Bush’s tax policies, I think they have been overestimated in terms of their positive impact. I do believe in reducing marginal tax rates, but none of the tax rate reductions that he has rammed through Congress are permanent. More than likely, they’ll be repealed or fail to be extended in coming years. I’m not really sure what the point is of bothering with these kinds of tax changes if they are not going to be made permanently to affect people’s behavior. I think that the tax cuts added perhaps a few tenths of a percent to economic growth, but undoubtedly there are other kinds of policies that would have done just as well. The growth that the administration is so proud of is essentially what we would have gotten if we had done nothing.

Bush says he wants to balance the budget, but the problem is that the financial commitments that have been made under this president will extend long, long after he is out of office. The fact that the budget may or may not balance by some measure at some point in the near future is essentially irrelevant to the basic fiscal situation. The problem is that once the baby boomers start retiring, the financial commitments he’s made will cause the deficit to rise dramatically, and some future president will have to deal with it.

On occasion Bush has made proposals and recommendations that I personally agree with, but they have been pursued with such ineptness that he has made things worse. He’s poisoned the well. An example is Social Security reform. I favor personal accounts, but Bush has gone about advocating this position in such an incredibly stupid way that in future years it will be hard for anybody to advance those kinds of options as reform proposals without being ridiculed. People will say, “Oh, that’s just the same old Bush proposal that nobody paid any attention to,” and you’re just not going to get any traction on it.

If Bush were listening to me, I’d suggest that we cut our losses in Iraq under whatever reasonable circumstances apply, but I’m not sure what he can do. At some point you just have to hope things work out or leave it to your successor to clean up the mess. It’s grossly unrealistic to think that this president is ever going to admit error in any way. He doesn’t listen to anybody. If there were anybody on earth he would listen to, it would be his father, and he clearly has not paid the slightest bit of attention to his father’s advice or to James Baker’s, Brent Scowcroft’s, or Colin Powell’s. You can’t reason with him. You can’t do anything except wait for the clock to run out.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- George W. Bush