This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

It is noon and the park is full of sounds: the click and clack of the electronic controls on the hoists, the clang and bang of massive metal plates, the ping-ping of hammers driving three-inch steel pins. There are also chortles, curses, and moans from the short little men who perform the job at hand: erecting rides for the carnival.

The carnival is setting up in a town in Central Texas that any carny would recognize as a good spot even if he had never played there. It has about a thousand people, is isolated from urban excitement, and is surrounded by a dozen smaller towns also hungry for diversion. The town is old enough to have a business district built of native stone and old enough to have trustworthy civic organizations that can put on a big countywide blowout like the one the carnival is setting up for.

There are better spots for carnivals to play, but better carnivals are playing them. The biggest, fattest, best-equipped shows in the trade are nowhere near this town in the middle of summer. The best events in Texas—the State Fair in Dallas, the Tri-State Fair in Amarillo, the Fat Stock Show in Fort Worth—are scheduled for the cooler months at the beginning and end of the carnival season. In summer most of the dozen carnival companies based in Texas are booked in the Midwest and won’t come back until fall; only smaller operations stay home during the season. This town is a good spot, but only on the generally lean Texas county fair and rodeo circuit—and only by the standards of an industry in decline.

Carnivals have lost their gloss, glitter, and kick. Forty years ago the sights and sensations that carnivals brought were novel. Today no game on the midway is as fast or futuristic as a video arcade. Especially for the generation that went to Viet Nam and saw the landing on the moon, the carnival is becoming a rustic anachronism. But carnivals have not completely lost their value as family entertainment. The midway offers mild surprises and a little spontaneous laughter to adults, whose leisure is too programmed too often. Taking rides is derring-do for teenagers too young to drive, and preschool children, though in many ways jaded by television, are fascinated by the spectacle of a crowd.

The short little men are unshirted. Their suntanned backs are streaked with black grease from the gears on the rides they mount. They move quickly, because the sun is hot and because they are used to their work: they are limber and strong—and it helps to be short because they must exert force inside small spaces, sometimes in bent-over positions. Their chests and backs pour out sweat; their tattoos glisten in the sun.

The tattoos themselves are worthy of comment. Jimmy,* a thin, almost miniature man of 36, one of the elders of the group, has his name, date of birth, and Social Security number engraved on his right upper arm, lest he forget. Jimmy might forget; he is not one of the brightest men on the midway. Beneath his personal data is a red heart outlined in blue. The heart is broken in half, and the inscription below it reads, “I Hate Love.” Perhaps Jimmy has cause to: he is a victim of lipomatosis, and a thousand tiny tumors are scattered across his face and body.

One of his co-workers, a bearded, aging East Texas hippie named Artie, has a blue spot tattooed at one elbow, beneath an inscription that says “OIL,” as if he were but one of the machines he erects. Several of the other ride jocks have the number 13 etched into their skins, for 13 represents the letter M, and M stands for the word “marijuana.” A lot of these men have Harley-Davidson emblems or biker slogans like “Live to Ride” etched on their bodies. But none of them owns a Harley, or any motorcycle, because none can make a down payment.

The tattoo that best speaks for this group of some twenty men is on Doyle’s forearm: “13 1/2.” Doyle says the number stands for twelve jurors, one judge, and half a chance for justice. Most of the men who work on the carnival circuit have served time in jail, and though most of them are young, not a few of them have seen the inside of a prison as well. Like Doyle, a handful of these young men came to the carnival as fugitives.

Two years ago, to get away from old acquaintances on both sides of the law, Doyle bought a bus ticket out of New Haven, where he was on parole, to Phoenix, where he hoped to start a new life. On the southbound bus he met Connie, a nineteen-year-old from East Texas. Instead of changing buses in Dallas for Arizona, Doyle went home with Connie to Longview, where they were married. He found work in the carnival as a ride jock, and today he and Connie live with their eighteen-month-old daughter in the front half of a school bus used to haul ride equipment from town to town. In his new life Doyle hasn’t run afoul of the law, and he takes only a limited pleasure in swapping cops-and-robbers tales with other carnies.

“Gambling is the invisible force that brings game agents and marks together on the midway. ‘My luck will be better than yours’ is the challenge taken up on both sides of the playing counters.”

“I was stupid, man, I was a kid, you know,” he usually says as preface to his confessions. “Like, when I got out of reform school, they got me a job as a motorcycle mechanic, and they were even going to send me to Daytona, Florida, for training. But me, I fouled up, got with some old friends, and broke parole again.”

Whenever Doyle speaks about his delinquent past, Connie smiles mischievously, as if his misdeeds proved his manliness.

“Hell, I was in so much trouble before I came to Texas,” Doyle will say, gesturing toward Connie, “that when I got married I didn’t even give my real name. Connie don’t know my real name yet—nobody does.”

Connie smiles again when he makes that claim, not because she has learned his real name, but because the occasion calls for a show of wifely pride. Connie believes that it is not her place to know anything her husband would conceal.

Because of his relative stability, sobriety, and keenness, Doyle is the sort of man that Firsts of May, or carny newcomers, seek out when a motor won’t start, or a chain breaks, or a component won’t fit on one of the rides. Because he and Connie are humble and open, and because they have an icebox and a television in their school bus home, carnies cluster at their quarters every night when work is done—and they are always welcome. Connie helps Doyle as much as he helps the other jocks, and her admiration for him is much like that of his fellow workers. When he and the rest of the men are sweating out a setup, she brings ice water. At night, when Doyle is operating his ride, Connie sits in a ticket booth with her baby, watching and waving at her man.

“Many game owners could take a small investment and make a modest living elsewhere as an entrepreneur. They reject the sucker life, as it is called, for reasons wage earners can’t figure.”

Doyle and the other men have staked out locations for the rides according to a carnival tradition. First comes the merry-go-round, then a series of other rides for small children—miniature cars, airplanes, and boats suspended from steel poles or chains, called punk rides in the trade. Next, the “majors,” rides like the “scuff coaster” (a mini–roller coaster), the Tilt-a-Whirl, the Octopus, the “scooters” (bumper cars), and the RolloPlane. Last, according to common practice, should come the “spectaculars,” the new generation of high-speed, mostly European rides. But there are no spectaculars at this carnival because the small-town circuit won’t bear the expense. The nearest this show gets to a spectacular is the Sizzler, which is an Octopus of advanced design.

In the traditional midway pattern, sideshows are set up at the bend of a horseshoe-shaped layout, with the rides at its center. This carnival has no sideshows, just as it has no spectaculars. Sideshows are passing from vogue; now they are ordinarily seen only at big state fairs and expositions. Rides are replacing sideshows in the carnival layout, leaving games and concessions on the arms of the horseshoe.

Mick is setting up his game, a rat wheel, on one of those arms, his back turned to the punk rides at the center of the midway. The rat wheel will be housed not in one of the modern travel trailers with a metal door on one side but in an old-style “stick joint,” a structure of wood and canopies. From his employer’s portable warehouse and workshop—a gutted school bus—Mick has unloaded some three dozen two-by-fours, each more than six feet long, and two dozen shorter sticks, all painted bright red. The sticks have hinges at each end, and Mick’s job is to connect them with hinge pins and bent nails. Once the sticks are hitched together, Mick will nail the canopies in place, then call for help from other ruffies in raising the components of the joint into the air.

A ruffie is a midway laborer, and Mick is ideally suited for the job. He is young, only 22, and his body is bricked with muscles built by barbell training. He looks like a Viking: blond, wiry beard—no need for preening or spraying here—pale blue eyes, short pants, hiking boots. His disposition is not ferocious, however; he is naturally genial, an important trait in a trade where cooperation is a ground rule. Mick would be a good candidate for any blue-collar job, except that he is a pothead and a fugitive. These two things tie him to the carnival; as a midway worker he can earn a living without leaving behind a paperwork trail, and he can smoke dope any time he can score.

Mick does not regard himself as a ruffie. He will tell you that he is a game agent—and in a way he is, because he operates the rat wheel. Game agents live on percentage pay. Each night at closing time, or “checkup,” the game owners and agents divide their gross. In a game like Mick’s, which pays cash to the winning players, the split is usually one third for the agent, two thirds for the owner. In games that award prizes, the split is usually one fourth, three fourths. At a good spot a game agent can earn $100 a night. He can sleep in a motel, send his clothes to a laundry, put gasoline in his car, call his wife or parents from a pay phone.

Mick doesn’t own a car; he sleeps in his employer’s bus; his clothes haven’t been washed in a week; his father, a dope dealer in California, is either in jail or on the lam, and though he knows where his mother is, Mick hasn’t telephoned her in months—she doesn’t want him calling collect. Mick splits the rat wheel’s take with his boss every night, but at the last few spots his net has been less than $25 a night, and that was only when the carnival was showing. On days when it was in transit or was being set up or taken down, Mick has lived on what carnies call the draw: the $10 or $15 paid ruffies and ride boys at the end of each day, including days on which little or no work is performed. Mick is a game agent, yes, but on this circuit game agents live and work like ruffies.

Gambling, the heart of carnival games, is the invisible force that brings game owners and some agents together with marks, or patrons, on the midway. Counting on plain luck, marks come to the carnival to beat the games. Carnies live off that notion. “My luck will be better than yours” is the challenge taken up on both sides of the playing counters. For marks, gambling is a momentary fascination; for carnies, it is not only their day’s work but their leisure too. On closing night at each spot, the game owners and carnival owners get together for drinks and poker or craps. Men like Mick’s boss, a tall, lean, mustachioed fifty-year-old man named Sonny, hear the closing-night dice rattling in their minds even as this show prepares to open. For some of them, their midway profits are but stakes for the closing-night games.

The rat wheel is a perversion of roulette. Its key elements are a box of live white rats and a wooden wheel about four feet in diameter. Along the wheel’s circumference are two-inch holes that lead to wooden drawers attached to the underside of the wheel. The holes and their corresponding drawers are painted in matching colors: red to red, blue to blue, and so on. At the center of the wheel is a large black circle, covered by an inverted aluminum pot that hangs from a rope. Mick puts a rat under the pot, then pulls on the rope to lift it. As the rat runs out, Mick spins the wheel on its tripod base and, to confound the animal further, sounds a buzzer overhead. The rat runs to the wheel’s perimeter and, encountering a fence of plate-glass panels, crawls for refuge into one of the drawers underneath. The mark wins or loses the game by predicting what color drawer a rat will escape to.

It is the novelty of the rat wheel that makes it a popular midway game; marks pay to see the rats perform. But the rats do not always act as expected. At the carnival’s last spot, when Mick let the rats out they scampered about on the top of the wheel but would not jump into the holes. Time after time, Mick had to stop the game, disperse a crowd of players, and force his rats through their paces to remind them of their jobs. The rats had forgotten because it had been more than a week since they had been called into service. They had not run at the previous spot because the game had been sloughed, or closed down. The police had warned the carnival’s booking company that no gambling would be tolerated on the midway, and Sonny had decided not to risk arrest.

Mick’s game was not the only one that had been sloughed. The over-and-under had been closed at the last two spots. In the over-and-under the mark predicts how dice will land: on the number seven, over seven, or under seven. If the mark calls seven and hits, the house pays him $3 for his $1. If the mark calls under seven or over seven correctly, the house pays dollar for dollar, even odds. Of course, the odds of calling and hitting seven on a single throw are greater than three to one, but then life is like that: the house has to make a profit. Over-and-under is a straightforward game, but it is gambling.

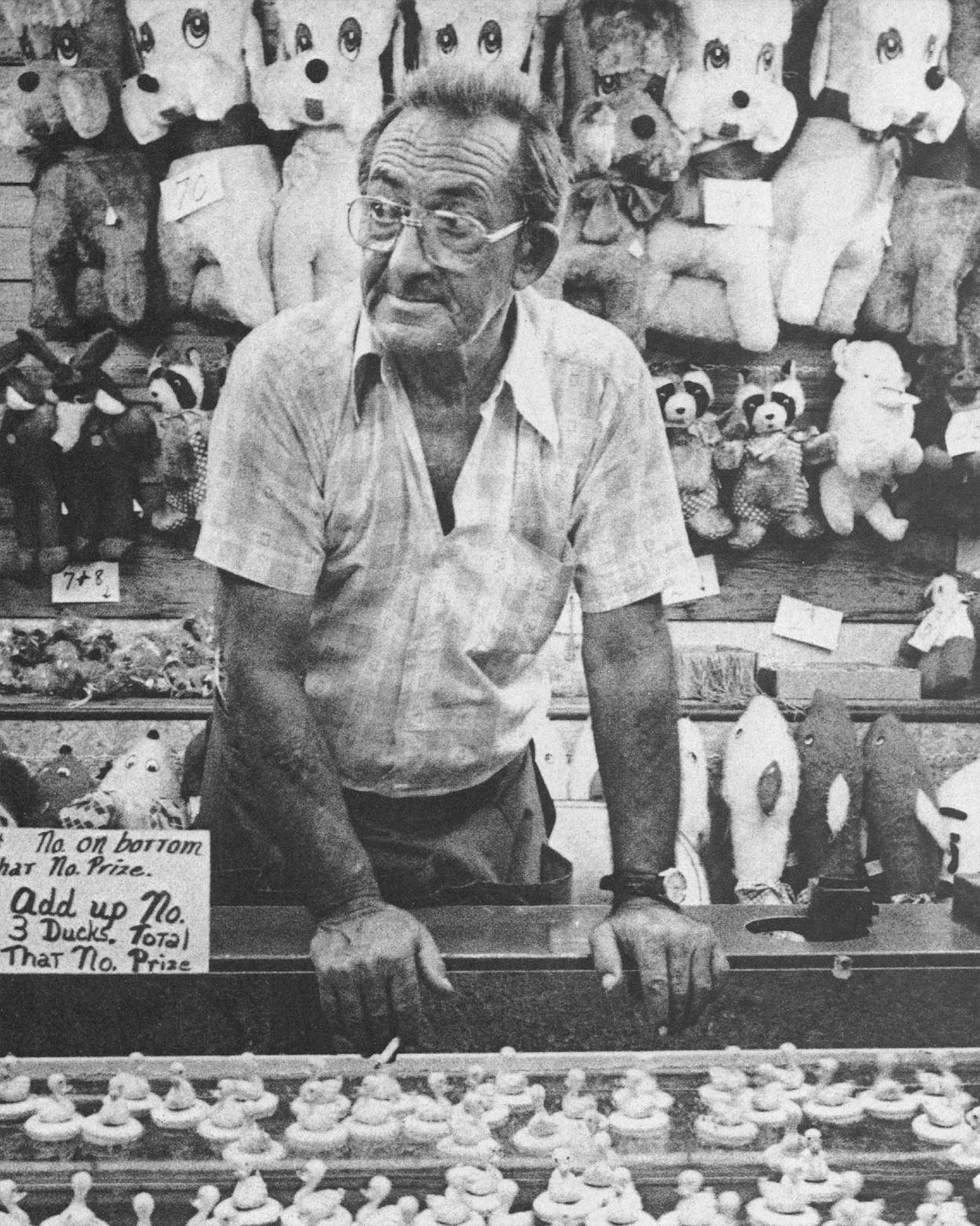

Carnivals in Texas occasionally have trouble with the police, partly because the state’s gambling statutes are broad and partly because few lawmen understand the sometimes disguised operations of midway games. Carnies classify games in three categories: hanky-panks, percentage or PC games, and alibis and flats. Hanky-panks are winner-every-time games, like the game in which floating toy ducks have prize numbers painted on their undersides. Percentage games, like Mick’s rat wheel and the over-and-under table, are gambling games, plain and simple. Alibi and flat games are rigged. In an alibi, the agent decides who will win and who will lose. Flats are games that cannot be won.

Alibis and flats operate on deceit and are controversial even in carnival circles; some companies won’t book them because they invite trouble. The most innocuous of the alibis is the milk bottle game. In this contest, three concrete milk bottles are stacked in a pyramid, and the mark is challenged to knock down all three with a single softball throw. What marks don’t suspect is that most agents weight their milk bottles with lead, making one bottle heavier than the others; sometimes a bottle weighs as much as twenty pounds. A mark can knock down all three bottles only when the agent places the heaviest one at the top of the pyramid. The agent will do that only if he’s got a big crowd—the kind of crowd carnies call a tip—or if the mark is a young lady with whom the agent wants to advance.

Most flats and alibis lend themselves to the techniques of buildup men, the elite among the midway game operators. A buildup is a game in which the mark, instead of winning a prize for successfully completing a single feat, must perform the feat several times. With each success, the buildup man totals the mark’s score, urging him to continue toward the goal and sometimes allowing him a round of free play. But when the mark fails, the buildup man cajoles him into spending more money under game rules that create a geometrically progressive risk. For example, in the screw pull, a game in which marks are required to knock down a nail ten times with a cue ball, they may be required to pay 25 cents to begin playing, an additional 25 cents after the first failure, 50 cents after the second, $1 after the third, and so on. The key to the buildup is the agent’s control of the game’s outcome—he can make it impossible for the mark to win. The rest depends on the agent’s persuasiveness—in carnival circles it is said that buildup men sell conversation—and his prudence. Suckers (the carnies’ term for townspeople) sometimes suspect that buildup games are rigged, and the smart agent is one who knows when to mollify a mark with a prize.

Even prizes come in shades of honesty at the carnival. On the bottom of the list are the “slum” prizes, the trinkets and small plaster of paris items awarded at hanky-panks and as consolations at many joints. Next up is the “rag-in-a-bag” category, small stuffed animals with unflocked cotton coverings. Most adult marks recognize the slum and rag-in-a-bag prizes as mere giveaways but feel they have beaten the odds if they win a piece of “crazy ball” stock—usually a stuffed animal 18 to 24 inches in height. Crazy ball merchandise costs the game owner about $2 per prize; often, a mark will spend twice that much trying to win, making the agent the real winner even if the mark carries home a prize. Victory for the mark comes only with a win of a “mike dog,” a large animal worth $5 to $20 on the wholesale market. Flat and alibi joints, which need not risk a loss to a mark, are recognizable almost without investigation of their games by the prizes they display for come-on value. They are hung heavy with “spoofers,” man-size stuffed animals with a wholesale cost of $100 or so. Spoofers are never awarded to marks.

Texas gambling statutes state that any bet made in public for anything of value on any game of chance or skill is illegal. But most law enforcement agencies tolerate hanky-panks and apparent games of skill, like the games played in alibi and flat joints. What they usually close down are games of chance, especially those in which marks play for cash rather than stock prizes. But in practice, local considerations shield most midway games. Ordinarily, a carnival does not show up at a spot without an invitation. It appears by contract with a county fair or other civic committee, and the carnival company pays a percentage of the gross receipts to the sponsoring organization. “Committee money” and the blue-ribbon character of committee members provide informal, but extralegal, immunity from arrest and prosecution.

So do people like Larry. A middle-aged, pipe-smoking, polyester-shirted man, Larry is the carnival’s “patch.” A patch is a game owner—never a carnival owner—who doubles as a legal fixer. He has one income from his joints and a second income from his role as bondsman and bribesman. When Larry is working a show, you’ll see him give mike dogs to cops’ families, one prize for each child. About an hour before closing time, Larry will sidle up to the joints he protects and say to each agent, “Give me a fin for the patch.” The agent takes $5 from the gross, and Larry goes off to patch up an irate sucker—or a cop—with money. After the day’s receipts are counted, game owners like Sonny will hold back 10 per cent of their gross, saying, “This is for Larry.” In exchange, if an agent from a protected joint is arrested for gaming or deception, Larry makes the bond. The patch was not present at the last two spots; that is why Mick’s rat wheel and the over-and-under were sloughed, along with some other games. But Larry is setting up for this town, as both game owner and patch.

As Mick raises his joint and Larry’s ruffies do the same a few yards away, their employers stroll the midway, talking shop and exchanging pleasantries. Like most of his peers, Sonny is a former ride boy, ruffie, and agent, a veteran of two decades or more on the midway. He is a married man with a son at summer camp and a wife who serves as his assistant and as a “stick,” or shill, for his games. He owns a travel trailer where he and his wife sleep and an old red Ford truck that still bears the advertising message of a poultry farm in the Midwest. He also owns a wheel of fortune, which is housed in its own trailer, and two or three stick joints, but he has neither the capital nor the manpower to open them at this show. He will be opening, in addition to the rat wheel, a checkerboard dart game and two hanky-panks, a balloon dart game and a cork gun game. If traffic on the midway is heavy—and Sonny expects that it will be—he will go to a pay telephone and call out several former and part-time carnies, known as “forty-milers,” to augment his labor force, doubling the number of agents in each of his joints. One agent will sweep the counters of money while the other calls in marks and calls out winning scores.

Sonny, who resembles Jeff from the Mutt and Jeff cartoon strip, keeps a cigar stub between his teeth and, when he is thinking, a stare on his face. He stares at the ground for a moment, standing underneath a tree just a few feet from Mick’s rat wheel site. He tilts his fly-fisherman’s cap askew, spits tobacco juice through his teeth, gnaws at his cigar, and continues staring. He has been talking with Pete, one of the owners of the carnival, about the price of opening the wheel of fortune.

Game owners like Sonny pay show owners like Pete for bookings. Owners of alibis, flats, and some PC joints pay a percentage of the gross and sometimes a flat fee as well; most other operators, including those who run food concessions (“grab joints”) and confectionery concessions (“poppers”), pay only a flat fee. The booking fee for Sonny’s wheel of fortune, Pete has told him, will be $150. After spending a few moments in thought, Sonny decides not to risk opening the joint. He knows from experience that this is a good spot, but he’d rather wait to spend his booking money at the next place down the line—a town on the Gulf Coast.

Sonny’s caution is based on a single consideration. For all its advantages, this town has one drawback; it is located in a dry county. Beer lots—carnival grounds on which liquor may be sold—are good spots for PC joints, alibis, and flats because a little drinking encourages the gambling urge in even suspicious suckers. Towns where liquor is sold are preferred by most carnies, and on the coast a good turnout of payday-happy shrimpers was to be expected. Generally speaking, educated or prosperous marks spend little at carnivals; the real income comes from momentarily solvent poor folk, teenagers, and males of any age or class who are tipsy enough to attempt to prove their prowess on the midway.

Most game owners, like Sonny, are good shade-tree mechanics, good lay carpenters, passable electricians, and fairly adept salesmen. They become jacks-of-all-trades on the carnival circuit simply by experience. Many of them could take a small investment—Sonny’s entire holdings are probably worth less than $20,000—and make a modest living elsewhere as an entrepreneur. They reject the sucker life, as it is called, for reasons wage earners can’t figure.

If on a good night an agent like Mick earns $100, Sonny will earn $200 from Mick’s joint (before fees and percentages are paid to the booking company) and will take in a similar amount from his other joints. At a three-day fair, a game owner might pocket more than $3000 in cash, with no taxes paid and none reported. Sudden rushes of cash, even if separated by weeks of little income, create a craving irresistible to Sonny and others of his class. “You get a few good spots in a row, you get on a roll, and you spend the rest of your life hoping to find a way to link the good spots together,” Sonny says.

This fair may not be a beer lot, but the signs of a good showing are already evident. They were evident even to the ruffies on the day the carnival pulled into town. For one thing, the carnival was not shunted off to fairgrounds on the edge of town, with no rest room facilities at hand. Instead, the show was given space in the center of the city park, next to the open-air pavilions where dances will be held three nights in a row. At other spots rodeo or fair dances are held at one location, the carnival at another—which puts too much distance between the marks and their predators. This community is looking forward to the show, and when the ruffies walk to town for purchases the townspeople often give them rides back to the park. At some other spots, when the ruffies go to town they are stopped by the police and questioned.

Perhaps the most reliable sign of a good turnout appears as the ruffies and ride jocks are setting up shop: the lot lice show up. Lot lice are children who hang around the carnival grounds, watching, begging prizes, and creating mischief. They are not welcome, but they are a welcome sign. In spots where preshow publicity and expectations have not taken hold, the lot lice do not show. But in this spot, by noon on setup day the grounds are crawling with curious kids, kids who will hurry home with a message: Daddy, take me to the fair.

Because there is pavilion space, because a good showing is expected, and because an annual celebration is a tradition with carnival companies, the wives of the game owners—many of them concession and game operators themselves—decide to give a potluck supper at the close of work on setup day. About sundown the owners disappear to their travel trailers to ice down booze for the celebration. The ride jocks and the ruffies go off to their trucks, buses, trailers, and tents to bathe with water from buckets and rubber hoses. By dark everyone is dressed as presentably as possible: ruffies and jocks in ungreased jeans, dustless T-shirts. Some one hundred carnies gather under a pavilion to toast the good fortune that had eluded the show for several weeks but is sure to return on opening day—or at the next spot down the road.

The ruffies, who are charged a six-pack of beer or the cost of one for entry to the potluck supper, are ecstatic at the display of hot home cooking: slabs of ham, pieces of fried chicken, bowls of pinto beans, plates of cornbread, and wedges of pie. It is the first square meal most of the jocks and ruffies have eaten in ten days or more. At the spot before last, the operators of a sideshow called the Elephant Pig had set up a carny kitchen in their trailer home. Ruffies could order supper each night at $2 to $3 per dish; at closing time there was another meal, usually for $1 to $2—and credit was extended when necessary. But the Elephant Pig has moved on to better bookings in the Midwest, and the ruffies have returned to their usual diet: midway sandwiches and convenience store fare.

After everyone has passed through the supper line, eaten, and chatted for a while, Pete calls for attention and presents the Wilson family—husband, wife, and two children. The Wilsons head the committee that arranged for the carnival to come to town. Dressed in Western garb, they wave at the carnies good-naturedly, and a few of the carnies wave back or clap.

But most of them are already gambling, even though it is only the night before the carnival opens, because the potluck supper has brought the carnival community together. About halfway down the concrete floor of the pavilion, some ten yards from the potluck serving table, a group of game and ride owners and their wives, along with a handful of buildup men, have started hurling dice against an empty Pampers box. The stakes are up to about $100, and a carny crowd is drawing in. The ruffies want to join but can’t because the stakes are too high. Before another hour passes, the ante has doubled. The players are drinking, whooping, and bad-luck cursing, enthralled by their game. On that concrete floor, the carnies have created their own midway.

About ten o’clock, though others are still crowded around the crap game, Doyle and Connie saunter off toward their school bus. Doyle sits down on the hood of a car parked nearby. Connie, her child in her arms, drags out a folding chair from the bus and sits down beside him. The two are soon joined by a middle-aged man who is a First of May.

Doyle and Connie left the pavilion because the sight of all that money disturbed them. Ride jocks and ticket sellers do not have the gamesmen’s mentality; they live for a salary, not to play their luck. The show, game, and ride owners are playing for more cash than Doyle and Connie will earn in a month, and in carnivals, where boss-employee relationships are nearly familial, it hurts to see paternal figures turning precious earnings into playthings. The First of May left the game because he was disheartened, too. Though he is an agent, his earnings are too small to allow him to ante up, and his maturity tells him that the perennial hope for better luck at the next spot is unfounded. An outgoing, somewhat bucolic little man, he complains to Doyle, who expresses his own disconcertedness.

After a while, Doyle and the First of May begin to talk about the future.

“Doyle, I watched you set up this morning, using that crane and lifting those steel plates and all. It’s like shipyard work, you know.”

“Yeah, what do they do in shipyards?” Doyle asks him.

“Well, they build boats and repair them. They lift and place and weld metal plates like you handle on the rides.”

“Huh, I didn’t know that,” Doyle says, in all sincerity.

“Yeah, when you get down on the coast you should check it out. With your muscle and what you know about mechanics, as young as you are, you might get a job as a shipyard worker.”

“Is there any money in it?” Doyle asks.

“Sure, plenty, maybe ten or eleven dollars an hour,” the First of May says.

“Yeah, but if it’s like that, I bet it will be like New Hampshire then. They’ll have a union or something, and what that means is you’ll have to have a relative in there to get a job.”

The First of May lowers his chin, reminiscing for a moment. He recalls the jobs he didn’t get before he turned 35—the witching hour for companies with retirement programs—and he tries not to remember the jobs he bypassed when he was too young to know an opportunity when it presented itself. After thinking it over, he agrees with Doyle.

“Well, maybe it’s like that,” he says. “I know I’ve been sent home from union halls, just like personnel offices. They told me to go home and wait, but they never called.”

“I wish I could make more money,” Doyle tells him. “But there’s always that problem. I’m sure the law has got my name in some computer.”

“I don’t reckon it will be that way forever,” the First of May comments.

“I don’t know,” Doyle says. “I guess that someday they’ll have too many names, and then maybe they’ll have to send some off to a storehouse, maybe.”

“You’re going to stay with the carnival until then?”

“What else?”

At this point Connie breaks in, apparently in an effort to console both men. “You know,” she says, “it ain’t so bad. Sometimes I think about this carnival and the only thing I don’t like is that when I’m sitting in the ticket box, sometimes I look out to see the stars at night. You can see them right now, you know, but that’s because we haven’t opened. Once the show has opened, you can’t see them, because the lights from the midway are too bright.”

The two men wince and nod and murmur in agreement. What Connie has said is true. The neons from the rides are blazers, and above them an orange-toned cloud of dust forms each and every night the carnival is open. The dust is thrown up by the hundreds of feet scuffling along the midway, looking for diversion. Carnies work, eat, and sleep under that cloud. Life in the carnival—it cuts them off from the stars.

*The names of all the people in this article have been changed.

- More About:

- Business

- TM Classics