When Houston oilmen circle their Eldorados for the night and hunker down around the campfire at the Petroleum Club to talk about the good old days, sooner or later one name always pops up.

Glenn McCarthy.

The loner. The poor boy who made good. The rich boy who made bad. The Wildcatter. The model for Jett Rink in Giant. Remember the time he made a half-million from a field that all the oil companies said was dry? That’s nothing, once he was a million and a half in debt, so he built a $700,000 house just for the hell of it. And remember the Shamrock opening in ’49, broadcast nationally on radio, when everybody who was anybody was there? And the time the Houston Country Club wrote him a letter saying that, all in all, they’d rather not have him around the place?

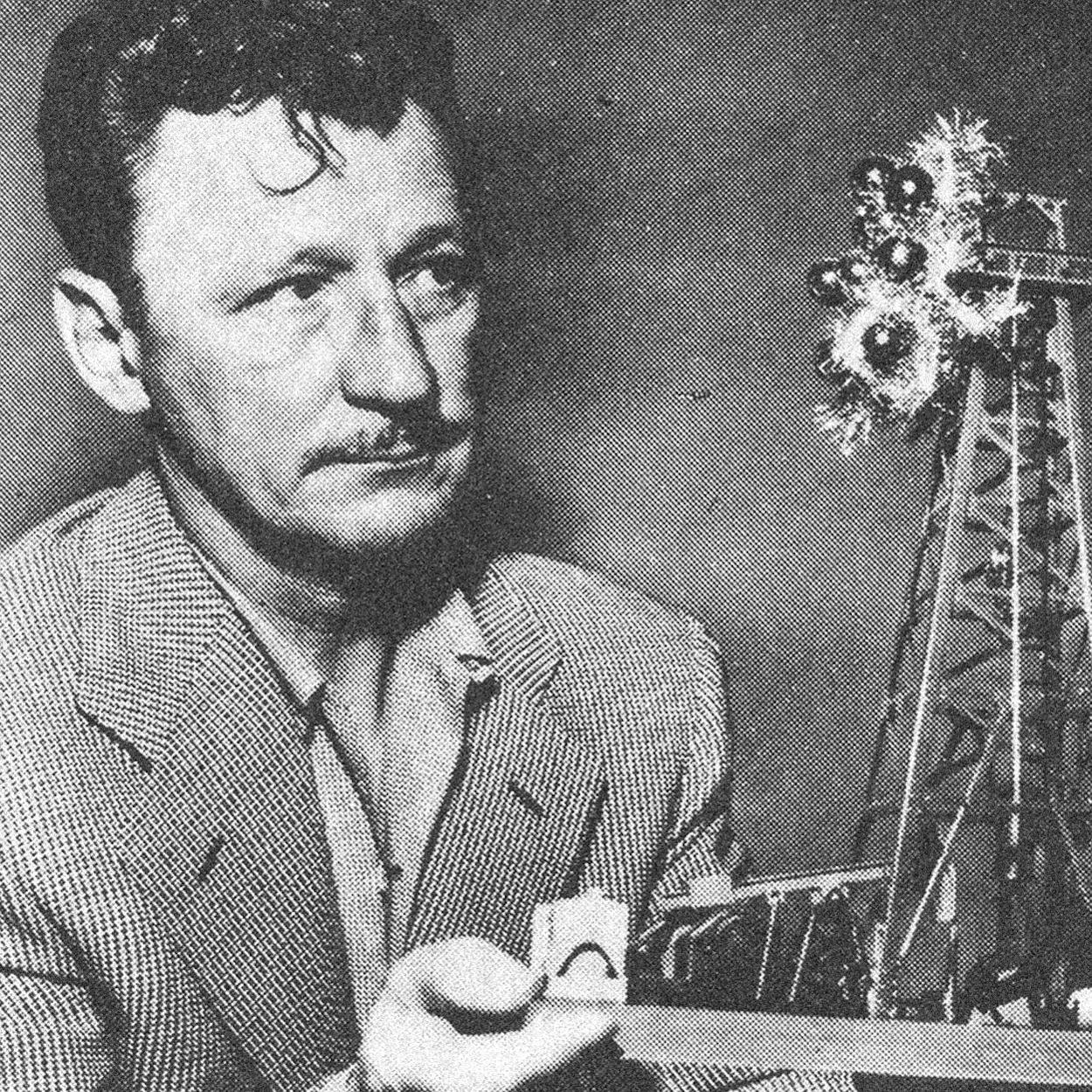

Yeah, those were the days, when—at least to the outside world—he was the personification of Houston, Texas, USA, 1950. Feast and famine, gusher and duster, whenever two people got together to fight or wheel or deal or all of the above, one of them was a smiling Irishman with curly brown hair and a dark mustache—Glenn Herbert McCarthy, the Wildcatter.

He came from Beaumont originally, the son of an itinerant oilfield worker, William McCarthy, who was a driller at Spindletop. Young Glenn was eight then, and carried a water bucket from the pump to the sweating workers. As he grew up, football became his thing. He was a star fullback at San Jacinto High School in Houston, then played freshman ball with Tulane. He went on to Texas A&M but was expelled (for hazing) even before the season started. He later played for Allen Academy at Bryan and for Rice.

When he was 23, McCarthy wooed and wed Faustine Lee, the 16-year-old daughter of T. P. Lee, a rich Texas oilman. Lee was upset, since Faustine had run away from high school to marry, but by then, Glenn could hold his own. After all, he was an oilman too—and soon he owned his second service station. So there.

But the oil game is like politics—once in the battle, it’s no fun sitting around on the sidelines. He sold one of his stations and bankrolled himself into a po’ boy hunt for oil. By the time McCarthy was 26, he had found two oil fields and extended a third. By the time he was 30, McCarthy rather had the hang of it. He struck at Anahuac, where the major oil companies had already poked around, finding nothing. Their geologists agreed it was futile, so no one paid much attention when a smiling young Irishman came in and started drilling. He drilled dry holes, too, just like the big boys. Then he started going deeper than ever, and, well, uh, it seems that there was some oil under Anahuac all the time.

In 1940, McCarthy struck again, this time in League City south of Houston. He hit it big. Real big. So big that he could go even deeper into debt, joy of joys, to $34 million, which the Equitable Life Assurance Society soon called in.

McCarthy was left with some oil interests in Egypt and Central America, the Shamrock Hotel, and the chance to start all over again, only this time without any service station to back him up. Since then, it’s been up and down, cold Brut and hot Bud. Time had him on its cover for February 13, 1950—the King of the Wildcatters.

Today the curly brown hair is graying. The face is ruddy and sun-tanned behind dark glasses. He doesn’t drink as much as they say—and claims he never did. The pace is a little slower, befitting a man who will be 67 on Christmas Day. And things are looking up. “It’s getting a little better now for the industry,” McCarthy says in his office in downtown Houston. “New oil is now $10 [a barrel] and the Railroad Commission allows us to operate at 100 per cent [of capacity]. But there are still a lot of obstacles. It’s not like it was 30 or 45 years ago.”

McCarthy is nursing along the Dobbin South, a gas and condensate discovery just north of Houston. “The Federal Power Commission [which sets prices for gas in interstate commerce] is holding the price down to 42 cents per 1000 cubic feet when the actual market price is a dollar-fifty.

“Now if they’d just leave the prices alone it would be all right. Look, at $10 a barrel here for new oil it’s still cheaper than the $13 to $22 the sheiks are selling it for.”

The high interest rates aren’t hurting McCarthy’s search for oil, since he doesn’t borrow any more. He doesn’t even like using a friend’s money. “You’ve got to be a gambler to be an oilman, but only gamble with your own money.”

The current oil shortage doesn’t surprise him, although McCarthy is loath to go around saying I-told-you-so. “As far back as I can remember, there were those oilmen saying that we were going to run out of oil,” he said recently. “In 1947 I talked before the House Banking Committee, and so did Everette De-Golyer, a great man, incidentally. And he told them and I told them, and nobody listened. Then we had the curtailment of domestic production. Prorated. You would spend $200,000 to drill a well, it would come in, and the government would tell you how much you could pump and for how many days a month.

“What happened? It became more lucrative to look for oil overseas. We got to the point where it was more lucrative for a Texas oilman to produce some sheik’s oil than his own oil right here. So we all went looking for other places, developing other economies rather than our own. Proration in this country curtailed profits, and stopped income. The well that cost $200,000 to bring in was allowed to pump only 20 barrels a day, at a dollar a barrel. OK, it cost five dollars just to take care of that well. Plus the taxes. Then they said I could only pump 18 days a month. It hurt the business.”

The recent change in oil prices has lifted the gloom from the oil patch, but McCarthy feels it’s only short-range help. “It’s getting better, but the harm has been done. Young men today aren’t coming into the oil business. It’s too risky and the profits aren’t worth the gamble. It used to cost ten cents an acre for an oil lease. Now it’s $35 to $50. Once I could drill for $45,000; now it’s upwards of $200,000.

“To turn things around, we’ve got to get young men back into the oil business. First, give consideration where it is due—put the incentive back to attract young oilmen. When you’re drilling at 2 a.m. on Christmas morning, and it’s freezing, you’ve got to have a good reason to be there.

“You’ve got to have incentive to go out and look for oil. You’ve got to have that to get men to risk everything in hopes that they’ll hit. You take it away from an oilman and what has he got to gain? He’s not going to do it for pleasure.

“So what if some oilmen were flamboyant and boisterous and loud? They were the men who worked their heads off, rain or shine, winter or summer. They risked and sometimes they won. Then what happened? A few Congressmen a while back decided that oilmen were getting top rich. They only heard about the winners. Well, there were others—those who went broke—and the Congressmen never heard about them. Back in 1945 there were 34,000 independent oilmen, and today there’s only about 10,000. Or even less.

“An oilman is a breed of person. They know what they’re talking about, what they’re doing. There are no middlemen in this business; you go out by yourself. It’s a gamble.”

The King of the Wildcatters, still courting Lady Luck and Miss Liberty despite the often-shoddy treatment they’ve given him, plugs along through the oil patch, still looking, still working, still going it alone. He commutes to Houston from his West Texas ranch now, having sold his mansion at Kirby and North Braeswood in 1972 (for $1.5 million). It’s a far different lifestyle from the rowdy, brawling Jett Rink, but then McCarthy thinks of himself more as Bic Benedict, the family-type homebody in the same movie.

But to the public he’s always been Jett Rink. Remember the time he got into that fight flying to Bolivia? Ha, that’s nothing, the night they opened Giant no one paid any attention to the stars, just to ol’ Glenn. Drilled more than 800 new wells, they say. He tried to build a domed stadium in Houston—offered to give the city the land, too—and everybody said he was crazy. Yeah, they said a lot of things about Glenn McCarthy.

- More About:

- Energy