Every November, as she has done for almost forty years, Nellie Connally readies herself for the reporters’ calls. She has her hair done in preparation for the cameras, and she buys flowers—yellow roses, typically—to freshen her home, a sun-washed two-bedroom condominium on the twelfth floor of a luxury high-rise, the Four Leaf Towers, in Houston. Because the story is always present in her memory, she doesn’t have to brush up for the interviews, and because she is a trouper—she wanted to be an actress, a long, long time ago—she always sounds as if she is speaking on the subject for the first time. The story she is perpetually asked to tell, of course, is the tale of that fateful day, November 22, 1963, when she rode in an open Lincoln convertible with the president of the United States, John F. Kennedy; his wife, Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy; and her husband, John Connally, the governor of Texas.

Every Texan of a certain age recalls the events that swept Nellie Connally into history: the fury of Dallas toward Kennedy’s liberal politics, the bitter, full-page ad in the Dallas Morning News addressed to the president that essentially accused him of treason (“Why have you scrapped the Monroe Doctrine in favor of the ‘Spirit of Moscow’?”), the adoring crowds that lined the route of the motorcade. “Mr. President, you certainly can’t say that Dallas doesn’t love you,” Nellie Connally said to Kennedy, turning around in her jump seat to fix him with a broad, proud smile as she uttered what has become the most famous line of her life. And then, three shots rang out within all of six seconds, changing the country forever. Of the survivors in the car, John Connally, seriously wounded, lived until 1993; Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis died in 1994. So it has come to pass that Nellie Connally is the last living soul to have experienced, firsthand, one of the seminal events of the twentieth century.

Nellie, as she likes to be called—you really can’t call her anything else after meeting her—makes an unlikely sage. At 84, she still moves with the hurried step of a happy sorority girl (which she once was); her blue eyes are unclouded and sly, as is her mind. She still wears a variation of the bouffant she wore in the sixties, and she has a closetful of sharp suits from Armani and Yves Saint Laurent, which she wears with aplomb; she enjoys sweets and the occasional cocktail, despite her doctor’s orders, and if you get her talking off the record, she will pretend to stick her finger down her throat to describe her feelings about certain former first ladies of the United States. This is a woman who wields the word “jackass” with complete confidence. “I have always been full of fun and full of the joy of living,” she explained to me, showing off her dimples. “I just restrained myself when I represented you.”

If this is the way Nellie Connally sees herself, others see her as a tragic figure, a witness to America’s loss of innocence. As Julian Read, John Connally’s longtime public relations adviser, elucidated, “The thing about Nellie you need to know is that she’s a survivor.” On the day he imparted this information to me, he was seated in Nellie’s living room under one of many portraits of the former governor that adorn the apartment. (This one had Connally surrounded by Texas symbols: oil wells, the Capitol, the state flag, Herefords.) Nellie listened attentively to Read’s pitch from a comfortable chair across the room, nodding and occasionally supplementing. She knew the Job-like recitation was coming, which in chronological order includes: the suicide in 1958 of her eldest daughter, Kathleen, at age seventeen; the assassination of the president and near death of her husband in 1963; John Connally’s failed quest for the presidency, which lasted for the entire decade of the seventies; the collapse of his real estate empire and subsequent bankruptcy in 1987; her battle with breast cancer in the late eighties; and finally, the death of her husband, whom she loved deeply for more than fifty years. “We had everything we ever wanted,” she told me simply. “We just lost it all.”

Except for her memories, with which she has had a long and ambivalent relationship. They are like the forty-year-old suit shrouded in dry cleaner’s plastic in the farthest reaches of her closet, the one she wore on November 22, 1963. It’s a jaunty pink tweed, with cheery oversized buttons, and she could still get into it if she wanted to. Nellie can’t bring herself to part with the suit, but she can’t quite hold on to it either, as time frays the seams and weakens the fabric.

John Connally has suffered a similar fate. For Texans who lived through his governorship, which paralleled almost all of Lyndon Johnson’s presidency, it is hard to believe how quickly and harshly time has erased his memory from the public imagination until, like Nellie’s suit, all that remains of his role in history is a single day in Dallas. In his day, he was powerful and popular and something of a visionary, who brought state government into the modern era. He was spoken of as a future president. An unauthorized biography of him by James Reston Jr. titled The Lone Star: The Life of John Connally, published in 1989, ran almost seven hundred pages and seemed to herald an enduring legacy. But the latest Encyclopaedia Britannica dispatches Connally as “an ambitious political figure” who helped elect three presidents and was “indelibly identified as the seriously wounded front-seat passenger who was riding in the presidential limousine in Dallas, Texas, when Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963.” A seventh-grade history text published earlier this year, Texas and Texans, mentions Connally only once, in a reference to a 1966 meeting with farmworkers who were marching toward Austin to protest working conditions in the fields: “His actions did not satisfy the unhappy workers, and they became more active in politics.” That is hardly the grand place in history that he and his followers—and Nellie Connally—believed he was due.

Now, it is through telling the story of the assassination that she keeps the memories alive. She has recorded them in a new book, From Love Field: Our Final Hours With President John F. Kennedy, with help from the Texas co-author of choice, Mickey Herskowitz (who also helped John Connally with his autobiography, In History’s Shadow). But in Texas, there are now more people born after November 22, 1963, than before it—Michael Dell, Lance Armstrong, Beyoncé Knowles, just to name a few. That the assassination has been subjected to the crushing callousness of history was brought home to me the day I sat with Nellie while she was having her picture taken.

I arrived to find her bossing the photographer around good-naturedly—”You’ve called me ‘beautiful’ more in the last hour than John Connally did his whole life,” she cracked. As the shoot wound down, she served coffee and candies, and the conversation turned, as it almost always does with Nellie, to that day in November 1963. With little prompting, she told a version of her story, and as she did, the living room, crowded with the photographer, his assistant, and a makeup artist—all decidedly youthful—grew deathly quiet.

“Wow,” someone said when Nellie finished. “When did you say that happened?”

Novelist Charles Baxter has called the Kennedy assassination “the narratively dysfunctional event of our era” because “we cannot leave it behind, and we cannot put it to rest, because it does not, finally, give us the explanation we need to enclose it.” This is not Nellie’s view of the event; the speculation and conspiracy theories intrigue her not at all. People looking for any new insights into the assassination—some clue that Oswald didn’t act alone or that the mob, Fidel Castro, Lyndon Johnson, or even John Connally was behind the killing—should look elsewhere. As Nellie carped one day, “Some of these people think Johnson did it. Some people think John did it. What kind of idiots do they think we were to plan that and then get in the car and sit there?”

By nature, she’s not a skeptic. Her narrative is instead more intimate, more feminine, and somehow, more frightening. Four decades of investigations and conspiracy theories have diluted the horror of that day, which she makes vivid again in her book. But more to the point, her book is a way to secure her life with, and love for, John Connally for posterity. In one way or another, that is the story she has been telling, over and over again, since the day they met.

“We were indeed a happy foursome that beautiful morning,” she wrote. They were all in their thirties and forties, ready to take on the world: the handsome young president, who promised the dawn of a new era; the governor, fresh from his role as Secretary of the Navy, who had been in office for only ten months; Jackie, glamorous and, to Nellie, a little intimidating, dressed in a pink Chanel suit and carrying a bouquet of red roses; and Nellie, also dressed in pink, carrying yellow roses. She’d been fretting for days that her suit would clash with the first lady’s, that the Governor’s Mansion wouldn’t measure up to the sophisticated first couple’s scrutiny, and that, in general, the Kennedys would find Texas lacking. The warm response in Dallas, then, was an enormous relief. “John and I were just smiling with genuine pleasure that everything was so perfect,” Nellie wrote. Suddenly, “a terrifying noise erupted behind us.” From her spot on a jump seat, she turned back to look at the president just in time to see his hands fly up to his throat. Then, Nellie turned back to meet her husband’s eyes. John Connally had fought in World War II and was a hunter; he knew that sound had come from a gun, but it was too late. A second shot rang out, and Connally uttered what has become one of the most remembered lines of that day. “My God,” he cried, his rich, stentorian drawl taut with fear, “They’re going to kill us all!” Then he collapsed. The second bullet had hit him in the back.

What happened next was, for Nellie Connally, a defining moment. As she wrote in her book: “All I thought was, What can I do to help John?” Her husband was a big man—he stood six feet two inches—but she pulled him onto her lap and covered him with her body. “I didn’t want him hurt anymore,” she explained, and so, when the third shot hit its mark, exploding Kennedy’s head and showering Nellie with bits of blood and flesh, she was exposed but her husband was not. Nellie felt her husband move underneath her, bleeding heavily but alive. “I felt tremendous relief,” Nellie wrote, “as if we had both been reborn.” She pulled his right arm over his chest to draw him closer and comforted him as if he were a frightened child: “Shhhh. Be still,” she said. “It’ll be all right. Be still. It’ll be all right.”

The driver pulled the Lincoln from the motorcade and raced to the hospital. “We were floating in yellow and red roses and blood,” Nellie told me. “It was a sea of horror.” While a team of doctors worked on the president, Nellie Connally wondered what to do. Who was treating John?

She became increasingly more frantic as everyone concentrated on Kennedy. The question racing through her mind was this: “How long do I have to sit here in deference to my president, who is dead? All this time I was trying to be so nice when that was the last thing I ever wanted to be. I was as alone as I’d ever been in my life,” she wrote. The only consolation was that her husband continued to moan in pain. “That was the best thing I heard, because I knew he was still alive,” she continued.

The doctors finally cut John’s clothes from his body and began to repair the damage. Nellie sat numbly by while the death of the president was announced, barely able to speak with her three children by phone, unsure what to tell them except that their father was still in the operating room. She broke down only once, when Lady Bird Johnson, a friend of more than twenty years who would soon become first lady, burst through the swinging doors of the emergency room. “She opened her arms wide and I flew into them,” Nellie wrote. “And I cried and cried for the first time.”

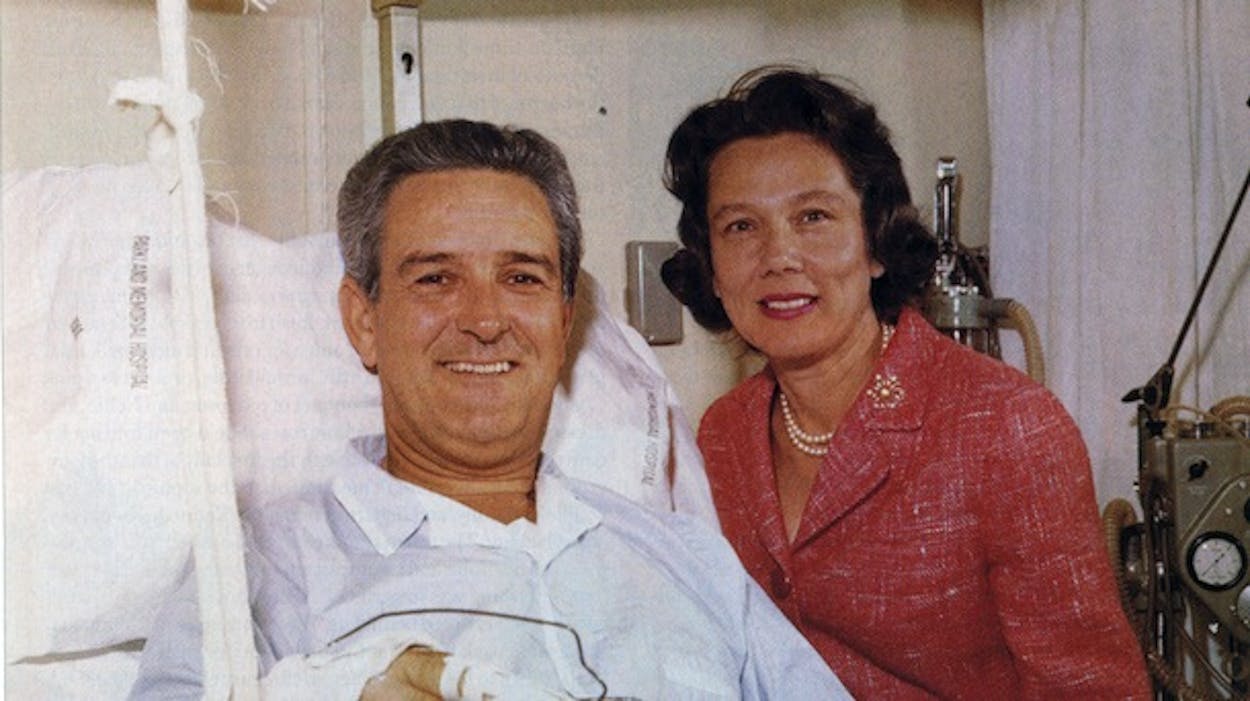

It was many agonizing hours later that Nellie got the news that her husband would live. A doctor told her that by pulling John over and covering him, she had inadvertently closed his baseball-size wound and, most likely, saved his life. Seeing her husband for the first time, pale but alive, Nellie leaned over the hospital bed and kissed him. “We had been through so much and had been spared,” she wrote. “We still had each other and could go on and fulfill whatever mission fate had in store for us.”

The Nellie who appeared on television in those horrible hours did not look like a woman in control of her destiny, nor did she look like the confident woman people know today. She was a very young-looking 44, drawn and almost unbearably fragile. She stood anxiously by her husband’s bedside when he was well enough to talk to reporters, not meeting the camera’s eye, steadying herself with the bed rail one minute, fidgeting the next, her bottom lip quivering, her chin tucked. She had still not recovered from Kathleen’s death; now she had nearly lost her husband in a terrible crime, and the signs of shock were unmistakable. Even so, she understood on some level that she had become a part of history. Two days after bringing her husband home from the hospital, Nellie went to a quiet corner of the Governor’s Mansion, picked up a legal pad, and recorded her account of the events, thinking that maybe her grandchildren and their children might want to know what had happened on that day. “I left Austin at noon on Thursday, November 21, 1963,” she began, with the harrowing account to follow.

Then she put her memories in a drawer and began to fashion the kind of story a woman of her time and place could make sense of. As she wrote in her book, she went to the beauty salon:

In those days, that’s what ladies did when they felt worn down and worn out: They got their hair done.

My hair dresser in Austin put me in the chair, looked me over like a Parkland surgeon, then gave a low whistle.

“Mrs. Connally,” he said. “Did you know there is a streak of white hair, two inches wide, down the back of your head?”

I sat bolt upright and reached for the mirror. “No, I didn’t! It wasn’t there three weeks ago!”

Shortly thereafter I made an appointment with our family doctor. During the routine physical, I asked him what might have caused the white streak.

“Shock,” he said matter-of-factly. “From what you say, you never screamed or even cried until after the event. You kept everything inside. That’s what happens to good little soldiers.”

That description is still the best characterization of Nellie Connally. She’s stalwart and dutiful and displays a well-developed sense of the absurd only when she’s sure the coast is clear. Her friends talk about her affectionately but with the care and concern of diamond cutters; maybe they see her as the perpetual political wife (never say anything that could hurt the campaign, which is ongoing), or maybe they simply do not wish to inflict, even by accident, one more scintilla of pain. Nellie becomes, in their accounts, a virtuous and devoted martyr, albeit one with a madcap sense of humor. Only occasionally will anyone admit that there’s been an enormous price to pay for her life, that just as there were enormous rewards for being married to the most classic of Texans, there were also enormous sacrifices. They leave that part of the story to her, and she recounts it with the facts but not the details. “A political wife has a hard go,” she told me, as she has told other reporters and friends in the past. “When people ask me who I admire, I say the political wife who has managed to get through her husband’s term without becoming a drunk, having affairs, or getting a divorce.”

Nellie managed. No one close to the couple has ever doubted that John Connally loved his wife—former lieutenant governor Ben Barnes was sometimes embarrassed when they’d smooch like teenagers in the back of a car he was driving—but Connally was a narcissist, and there were always other women around, the bored wives of very rich husbands, the political groupies. “Nellie was realistic about the kind of husband she had,” Mickey Herskowitz told me. “She knew early in her marriage she had to have a philosophy about it.” She has repeated that philosophy in countless interviews and repeated it to me, as a shield against further inquiries: “As long as he came home to me at night, I didn’t ask any questions,” she said. “And he did.” She was, after all, his wife, the mother of his children, the one with whom he took long drives in the Hill Country and the one with whom he attended social events all over the world. Nellie’s quality time came after the parties were over, when the couple would stroll alone together through the empty streets of some of the world’s greatest cities. To this day, there are many places Nellie Connally has seen only in the dark.

Her memory of their first meeting seems right out of a Texas romance novel. In 1937 Idanell Brill was a star on the University of Texas campus, with more than her share of suitors. She wasn’t beautiful in the conventional sense, but she was petite and lively and unafraid—sexy, in other words. “I was walking to the student union building, and this young man was coming my way,” she told me, her voice softening at the memory. “God, I never saw anything as good lookin’ as that in my life. Tall, slim, black hair. We were separated by about twenty-five feet. When we got opposite each other, we just looked at each other and that was it. Poor guy, he didn’t know his bachelor days were over.” Soon enough, however, the terms of their relationship were established. “All I know is, I was the star, but the roles very quickly became reversed,” she told a reporter several years ago.

The Sweetheart of the University had fallen in love with the ambitious president of the student body, a young man raised in poverty in South Texas who wanted to make damn sure he never had to return to it. (Connally’s father, a heavy drinker, had scraped out a living as a farmer, a bus driver, a butcher, and a barber in an attempt to support seven children.) Nellie came from a family that was better off but not wealthy. Her father, a hunter and fisherman, worked alongside his father at the family leather shop, one famous for making holsters for the Texas Rangers. While John Connally’s childhood was deprived—his happiest Christmas was the year he and his four brothers received one football as their only gift—Nellie’s was rich, in spirit at least. Her mother in particular was a lively, strong-willed woman who never let disappointment slow her down and imparted that lesson to her children. When Nellie says, “I only look forward, never back,” it is her mother talking, but the truth is that in her own life, she has had to do both.

Like so many relationships of that time, Nellie and John Connally each found in the other what he or she lacked—or could not express. He had the drive; she had the stability. He was formal and occasionally severe; she was unpretentious and irreverent, her compassion making up for his arrogance but without illusions. Several years before John Connally’s death, Herskowitz was at the family ranch when an old college classmate teased Connally about the wide swath he had cut as a student.

“That was a whole different John Connally,” the governor insisted.

“Oh, no, it isn’t,” Nellie argued, grinning. “He’s just the same. Vain, arrogant, and pompous—the three things every woman wants in a man.”

In late August, Nellie and I drove to the LBJ ranch for an annual event, the laying of a wreath on LBJ’s grave on his birthday. The ranch was a four-hour drive across Central Texas from Houston, and to make it on time, we had to leave at around five in the morning. Nellie came downstairs briskly, dressed sharply in a pin-striped, waist-cinching Armani suit and, planting herself in the back seat, groused good-humoredly about the tight seat belt and the design of the car’s headrest, which blocked her view of the road. She reminisced steadily as we headed west, while the sun came up and mist lifted off the hills beyond Columbus. No one would have known that she was ambivalent about making the trip, torn between reading the final galleys of her book and her loyalty to the crowd that was her life for so many years.

As we approached the sprawling, oak-shaded ranch house, Nellie grew more animated. She hadn’t been there in years, and every landmark—LBJ’s birthplace, the cemetery, the road (now closed) that used to bring visitors across the Pedernales—seemed to remove a year or two until, by the time she leaped from the car, she was as giddy as a teenage girl.

It was an unseasonably cool morning, and until Nellie made her entrance, everyone had been milling about respectfully, sipping coffee from speckled tin ranch cups. LBJ’s daughters, Luci and Lynda Bird, were there with their children, along with some old LBJ hands—Larry Temple, Julian Read, Ben Barnes—and the widows of others—George Christian’s wife, Jo Anne, Walt Rostow’s wife, Elspeth, and finally, Lady Bird herself, now ninety, who, due to a debilitating stroke, was rolled out in a wheelchair.

Nellie amped up the scene. She flitted and fluttered through the crowd, hugging, kissing, and squeezing almost everyone on the lawn. She craned her neck as she threw her arms around Barnes, nodded sympathetically as she listened to Luci and Lynda, bent over Lady Bird to kiss her hello. Little exclamations of joy and surprise followed her wherever she went. At the graveside, she sat among the widows, but while they were silent and stoic, she snuggled next to the former first lady while she listened, beaming, to a soloist who delivered an a cappella rendition of “America the Beautiful.” When he finished, Nellie shook her fists in victory. She was back in her old role, pulling the group together and giving it life, as had been her job from her earliest days with the Johnson crowd.

Nellie and John were married in 1940. By then her husband had already caught Congressman Lyndon Johnson’s eye, and the protégé was working late into the night in Washington, D.C., answering constituent mail and plotting political strategy. (Johnson was supposed to be the best man at the couple’s wedding but never made it to the ceremony.)

Nellie didn’t quite know what to make of Johnson at first. “I was not really political,” she explained. “I just knew that this was a powerful man and he was going to be somebody.” She did notice that he couldn’t relax and that he was extremely coarse; he ate off her plate after finishing what was on his. She took it upon herself to lighten his dark moods with little ditties and tried to be his receptionist, briefly, but left sometime after he threw a book at her when she accidentally cut off a big donor. “It took me a while to love Lyndon Johnson,” she admitted.

While Connally worked for Johnson, Nellie cooked dinner, kept house, and tried to create a life for herself. At one point, she considered joining a theater group in Falls Church, Virginia, but her young husband wouldn’t hear of it. “Let me ask you something,” Nellie told me, quoting John. “What if there’s a special dinner and you were in rehearsal?” When she said she’d go to the rehearsal, Connally shook his head. “I don’t think you’d better hook up with them,” he told her, and she didn’t. “Little did I know he would put me on a stage much bigger than Falls Church,” she said. “I had to act, and I had to be real good.”

When the war started and both husbands joined the military, Nellie shared an apartment with Lady Bird, who ran Johnson’s congressional office in his absence. Again, Nellie took on the role of cheerleader, filming skits in which she cast Lady Bird as a femme fatale and sending Lyndon cheery notes. “I really threw one last PM,” she wrote him. “I had six girlies out for a good drink, dinner, and a wild poker game. After drinks, I quit worrying about how my dinner would taste, because I could have fed them steamed grass and mud pies for all they cared.”

When the war ended, John and Nellie moved to Fort Worth; John traveled frequently to Austin and Washington as a lobbyist for Sid Richardson, the legendary Texas oilman and uncle of the Bass brothers. Nellie was, by then, the mother of four children, an enthusiastic if at times eccentric parent. On trips, she dried diapers by rolling them up in the car window and letting them flutter in the breeze; at home she allowed the children to have a dog even though she was deathly afraid of all animals, large and small. By then the family was living on a grander scale, taking their cues from Fort Worth’s old wealth, the Carters, Moncriefs, and Fortsons. “They just had so much that we didn’t have,” she told me. “I learned from watching them.”

Their lives seemed nearly flawless until March 1957, when the Connallys’ eldest daughter, who was sixteen, started dating eighteen-year-old Bobby Hale, the son of a former Texas Christian University football star. As John Connally recounted in his autobiography, Kathleen, or KK, was a bright, headstrong girl who had suddenly grown rebellious. “Nellie and I were both perplexed and agitated,” Connally wrote. “We could hardly talk about anything else. We knew her behavior was irrational.” John and Nellie came to suspect that Kathleen was pregnant; as Kathleen continued to deny that fact, the Connallys’ home became a battleground. Finally, in frustration, John Connally slapped his daughter, an act he would regret for the rest of his life. The next morning, he left for another business trip to Washington, and that night Kathleen loaded her clothes into the family station wagon while Nellie, he wrote, “pleaded and cajoled and raged. She drove off with her mother begging her to stay.”

After several agonizing days of silence, the Connallys got a letter explaining that the couple had eloped; Kathleen was living in a squalid boardinghouse in Tallahassee with her new husband. It was March 1958. John made one dispiriting visit to Florida; within a few weeks, he got the call in which he learned that Kathleen had committed suicide.

Lyndon and Lady Bird came to the funeral. It was, Lady Bird later wrote, “As painful a time as I can ever remember. John was just like a granite cliff, and Nellie was her sweet, warm, loving self. There was a whole lot of us out at their house. Love brought us all. We yearned to make it less painful, and there was no way to do it.”

John Connally made public mention of Kathleen’s death only once in his life, in his book. He wrote the chapter swiftly, late at night, and punctuated the recounting of his daughter’s death with a promise: “This is the first time I have ever discussed it in any detail, and it will also be the last.”

Nellie does not speak of Kathleen either, nor did she choose to write about her death in her book. “We lost her and I never got over it and I never will. There’s hardly a day that goes by that I don’t think of Kathleen,” she told me. “I will never get over thinking there is something I could have done to help her.” But at the time, she had three more children to raise. “I did the best with what I had and moved on,” Nellie said on the drive back to Houston. Then, for just an instant, she allowed herself to look extraordinarily tired.

For six years spanning my childhood and early adolescence, John Connally was my governor. I was nine when the Kennedys and the Connallys drove by my elementary school in San Antonio, just a day before the assassination, and he was a Zelig-like figure in most of the American history I witnessed as a young adult. These facts may explain why I was taken aback by my first visit to Nellie’s condominium. It is almost impossible to think of a home in the Four Leaf Towers as reflective of diminished circumstances, but if you grew up, as I did, on John Connally stories, you probably would have thought that too.

The place is pretty and well appointed but a little overcrowded with Connally memorabilia. The reason for this is not that Nellie has intentionally built a shrine to her husband but that, because of the bankruptcy, this is all she has left. They’d planned to retire to their Picosa ranch, she told me. He would commute (with his own plane and pilot) from South Texas to Houston, where he would run the new Sam Houston pari-mutuel horse-racing track while Nellie waited back at the ranch. Maybe that’s why Nellie’s condo had seemed so small: because the Connallys had lived so large.

The time between the assassination and John Connally’s bankruptcy spans almost 25 years, during which he managed to pack in several careers—corporate lawyer and rainmaker, Secretary of the Treasury, presidential candidate, real estate developer, and racetrack promoter—and never seemed to falter, at least from his perspective. “Connally wasn’t given to great periods of introspection as to whether he was a great fellow,” noted Houston’s former mayor Bob Lanier, who was not only a political associate of Connally’s but also a River Oaks neighbor. “Johnson had great self-doubt; Connally was very self-assured.”

He moved easily from one world to another, from business to politics and from Democrat to Republican—perhaps too easily. When he resigned as Richard Nixon’s Treasury Secretary, in 1972, to head a group called Democrats for Nixon, Johnson supposedly said, “I should have spent more time with that boy. His problem is that he likes those oak-paneled rooms too much.” Three months after LBJ’s death, in January 1973, Connally switched to the Republican party. Liz Carpenter, Lady Bird’s press secretary, weighed in with “It’s a good thing John Connally wasn’t at the Alamo. He’d be organizing Texans for Santa Anna now.”

Even so, to Connally it seemed like the right thing to do: The Democratic party, he said, had been captured by Northern liberals. When Vice President Spiro Agnew resigned under a cloud of bribery accusations, Nixon, dazzled by Connally, wanted to appoint him to fill the vacancy. (“They didn’t have many friends,” Nellie told me. “So we tried to be their friends.”) But powerful senators in both parties blocked the appointment, and soon Connally was facing his own bribery accusations over a contribution he had received from milk producers while he was Treasury Secretary. He was acquitted but fatally wounded politically; when he ran for the Republican nomination in 1980, he spent $12 million and won exactly one delegate. “I reminded everybody of Lyndon,” he told a reporter glumly.

He tried real estate, partnered with his old protégé, Ben Barnes, but when oil and real estate prices crashed in the mid-eighties, so did they. Then there was Connally’s daring rescue, with his close friend oilman Oscar Wyatt, of several American hostages held by Saddam Hussein in 1990. These were the kind of events Nellie Connally was referring to when she told me, “We had our ups and downs.”

At the height of the Barnes-Connally partnership, Nellie and John had amassed enough money to compete with the flashiest eighties moguls, including their friend Donald Trump. The Connallys had homes in Houston and Santa Fe, as well as a 3,900-square-foot penthouse in a condo on South Padre Island. (At some point, they sold their house in Jamaica, the one they’d purchased in the seventies as a possible Caribbean White House.) But their most important acquisition was the Picosa. Connally bought the spread near Floresville while he was governor, and as his fortunes improved, so did the Picosa’s. It was their showplace: He turned the land a rich, loamy green by importing coastal Bermuda grass. He and Nellie covered the walls with the finest Western art and imported stair railings from an old London embassy. They built an extra floor to accommodate an antique banister. They furnished the dining room with a massive table and carved, high-backed Spanish chairs, two cushions of which Nellie needlepointed with their initials. The bricks in the fireplace came from the old Texas Capitol building; a floor of swirling black and white marble came from an old English mansion. (“When we went shopping, he was as bad as any woman,” Nellie confessed.) Eventually, the ranch would include a main house, a guesthouse, a swimming pool, a tennis court, a skeet-shooting range, a landing strip, and an enormous rose garden behind the house. But by 1987, John Connally had debts of $93.3 million and assets of only $13 million. He had had such confidence in his business acumen that he had personally guaranteed his investors’ money, and now he had to pay it back. Nellie does not count the bankruptcy as one of the “three bad days” she told me she’d had in her life—those being Kathleen’s death, the assassination, and John’s death—but it was, nevertheless, “a sad time.” Reporters could not help but frame the four-day auction of the Connallys’ possessions as a referendum on the Texas myth. Publicly, the couple promised to make a comeback, but privately, they were devastated. “We would lie in bed at night, wide awake, not talking to each other, our minds racing about what was happening to us,” Nellie told me. “We knew we couldn’t start over again in our seventies.”

They presided over the liquidation, Nellie said, “even though it was like cutting off our arms and legs.” But the dignity and humor with which they conducted themselves during the proceedings helped to resurrect Connally’s reputation and to cement Nellie’s. He would take the mike from the auctioneer and regale the audience with the history of an item; she would fluff the pillows on sofas on their way to the auction block. Their closest friends and biggest fans bought the few items they treasured most—Nellie’s wedding silver, for instance—and, after a decent interval, returned them to the couple. But everything else was gone.

To get through it, she relied on friends and the unexpected kindness of strangers. One woman offered to send $50 to pay any of the Connallys’ smaller bills. Another woman called for advice. She was living in a small town where she felt shunned because she wasn’t making any money. What should she do, she asked Nellie.

“How old are you?” Nellie asked her.

The woman said she was 30.

“Oh,” said Nellie, who was then 69, “if I could just be thirty again. What’s the matter with you? Get yourself to a new town, get yourself a job, and start living.”

Unfortunately, circumstances precluded Nellie from following her own advice. She was lying in bed one night in 1988, almost asleep, with her hands on her chest. “My little finger felt something,” she told me. “I sat straight up in bed. I knew exactly what it was.” For several weeks, she told no one—she was on the committee for the one-hundredth anniversary of the Texas Capitol and didn’t want to put a damper on the party. “I couldn’t bear to tell all those people, and I didn’t want ’em all saying, ‘Poor Nellie, poor Nellie,'” she told me. She went to the party, suffered an anxious weekend afterward—”Saturday I thought about a lot of things and Sunday I went to the hospital”—and had a mastectomy after doctors found she had breast cancer. Her husband was sitting across the room, dejected, when she came out of the anesthetic. “Nellie,” he asked, “Do you think the stress of our bankruptcy caused your cancer?”

She was groggy from the drugs but still knew an opportunity when she heard one. “John,” she said, “if stress causes cancer, I should have had this fifty years ago, because I have been under stress since I met you.”

After her recovery, John worked their way back to financial comfort. He had retired from Vinson and Elkins (where he had also worked as a name partner upon retiring as governor) in 1985. His old friends Oscar Wyatt and Charles Hurwitz put him on the board of their respective companies, Coastal and Maxxam. (He also modeled for Hathaway shirts, wearing an eye patch, an inside joke evoking the company’s earlier ads that featured a similarly dressed pitchman.) Connally threw himself into the creation of the new racetrack, which was backed by Hurwitz, and in his off-hours planned a fundraiser for the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation, with Nellie as the honoree. Barbara Walters and Donald and Ivana Trump showed up to honor her, and Richard Nixon played “Happy Birthday” on the piano. It may have been the first time in their lives that Nellie was the star of the evening instead of her husband; to the Connallys’ friends, the night seemed to signal a new start for both of them.

But then, in May 1992, John began having trouble breathing. He got so sick that Nellie had to call 911. “Well, Nellie,” he told her, “you saved my life once more.” No one was particularly worried at first, because no one could believe that anything as minor as a lung infection could slow John Connally down. He may have felt differently. “If anything happens to me, sell the Picosa,” he told Nellie. “It’s free and clear.”

When he did not respond to treatment, Nellie asked her friends to pray and even brought Billy Graham to see him in the hospital. A few days later, she called the evangelist to deliver the sermon at the state funeral, in Austin. No one there, least of all Nellie Connally, quite knew how she was going to survive without her husband.

John Connally, who had lived like a billionaire, left an estate reported to be worth only $500,000. Within two years, Nellie was calling her children down to the ranch. “Take what you want,” she told them. “This is your heritage.” The children flipped coins over the belongings; the ranch went to some wealthy caterers from San Antonio. Nellie returned only once. “It’s not mine anymore,” she told me. “It’s beautiful, but I have no desire to go back.”

When John Connally began working on his autobiography in the early nineties, some thought was given to the idea that Nellie might do the same. An agent shopped a proposal around New York publishing houses, but no one, it seemed, was interested in the recollections of the wife of a former Texas governor, even if she’d been married to John Connally and even if she’d witnessed the assassination. Nellie’s notes, pushed to the back of a file drawer in 1963, remained just where she had left them.

Then, one day in 1996, she was searching through some files when she came across some papers torn from a legal pad. “What in the world is this stuff?” Nellie asked herself. She pulled the pages from the file folder and looked closer: It was the notes she had written after the assassination. “This is good,” she told herself as she reread them. “I did this and this is good.” Her husband never saw those notes—she hadn’t thought they were important enough to read to him. And, as she told me, “We would have fought over every paragraph.”

But now Nellie felt differently. “I just thought somebody ought to hear them,” she explained. And so she began reading them to small groups; initially she read without stopping or ever looking up from the page. She first read the notes to the Official Ladies Club, a group of political wives, in Austin. Then she gave another reading in Dallas. The response convinced her that, as a shy, 44-year-old political wife, she had created something of lasting value. (“Forget the magic bullet, the grassy knoll, triangulation, the Cubans, the mob, the CIA, the Warren Commission, and Oliver Stone,” Alan Peppard wrote in the Morning News in 1997. “No amount of analysis of the JFK assassination can prepare you for the emotional sledgehammer that comes from hearing the former first lady, Nellie Connally, quietly read her personal notes describing the scene in the back of the limousine in Dallas on November 22, 1963.”)

Then, a year ago, Larry King asked Nellie to come on his talk show to recall that day in November 1963. She was nervous, but, as usual, the story came alive with her telling. An agent named Bill Adler happened to be watching—he had represented both John Connally and Herskowitz for Connally’s autobiography—and it struck him that the time was now right for Nellie’s story. There were many people who had been born after the assassination, and her version of events would seem fresh. “It was like doing a book with Lincoln’s wife, who was with him when he was shot,” he told me enthusiastically. “No other assassination books coming out this fall will have a firsthand account.” Even if Nellie wasn’t the wife of the president at the time, Adler was right about the renewed enthusiasm for the assassination: He sold the book to a new publishing house, Rugged Land, on the basis of an outline.

It took Nellie and Herskowitz only a few months to write the book, but doing so resurrected old hurts. The awkwardness that always existed between Jackie Kennedy and Nellie had soured before the former’s death. In William Manchester’s Death of a President, Jackie had insisted that Nellie and John were screaming in the car, something Nellie always denied. Nellie had asserted in her speeches that Jackie could have been trying to get out of the car when she crawled across the trunk that day—”The car at that time was not a good place to be,” Nellie told me—while Jackie claimed she had been trying to retrieve her husband’s brain. These actions may explain why the executors of Jackie’s estate refused Nellie’s request to use in the book a note Jackie had sent her after JFK’s death and Connally’s recovery. Likewise, Nellie sent Caroline Schlossberg a note; she wanted to meet with JFK’s daughter before she died. She longed to tell Caroline about her father, how happy he had been in Dallas that day, how promising the world had looked then. She never got a response.

Nellie’s young publishers, in contrast, could be a little too enthusiastic about sharing her memories. She had to nix a Texas book tour, for instance, that followed the same itinerary as the one in 1963. Nellie also refused to let them describe her in the book as “tony.”

On my last visit to see her, Nellie wanted me to meet her children. Dutifully, they all collected in her apartment one day in early September, cheerful adults in their fifties who wore the features of both parents equally. On that day, Nellie was happier than I’d ever seen her. She fussed over her kids, bantered with them, fed them cheese dip mixed with chili. When the joking died down, they praised her strength to me, but she demurred. “I am strong because of your father,” she insisted. Her kids, products of another generation, argued the point. “You’re not who you are because of him,” her eldest son, John Connally III, countered. “You’re who you are because of you.” Nellie listened closely, her eyes darting quizzically from one child to the next, but she seemed unconvinced.

Then, once again, the talk turned to the assassination, and once again, the family of John Connally tried to make sense of the events of that November day. They argued over what happened when, over who did what. When had Nellie told them the president was dead? When had the children learned their father was all right? Why had the eldest child, John, been able to go to Dallas when the younger ones had been left at home? (The answer: because he hadn’t asked permission; he’d just gone.) Everyone had a slightly different version of events, and finally, Nellie had had enough. She shook her head and hugged herself, as if warding off a chill. Then she allowed herself one moment of wishful thinking. “Well,” she said, “I’m glad that deal is over.”