Donald Trump didn’t save the coal industry, reindustrialize the Midwest, eliminate the trade deficit with China, or finish the wall along our southern border, much less make Mexico pay for it. But there was one campaign promise he did keep: to appoint ideologically conservative judges to the federal bench. Over the past four years Trump has managed to confirm three Supreme Court justices and 226 lower court judges—the most confirmed in one presidential term since Congress expanded the size of the courts under Jimmy Carter.

Today, almost a third of active judges on the thirteen circuit courts were nominated by Trump and confirmed by the Republican-controlled Senate for lifetime appointments. Because the Supreme Court hears relatively few cases each year, the appellate courts act as the final arbiter for the vast majority of cases appealed from one of the country’s 94 federal district courts. Over the decades, each circuit court has developed its own ideological profile based on its roster of judges and its case history. The Ninth Circuit, based in San Francisco and covering a broad swath of the western U.S., is widely considered the most liberal appeals court, which is why so many of the major lawsuits challenging Trump administration policies—on immigration, the environment, civil rights, and abortionhave been filed in California.

With Joe Biden poised to take office, though, the action is about to shift to the Fifth Circuit. Based in New Orleans, with jurisdiction over Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi, the Fifth Circuit has long been the country’s most conservative appeals court. Just as the Ninth Circuit has been a magnet for anti-Trump litigation, the Fifth Circuit was conservatives’ favorite venue for legal challenges to the Obama administration. Many of those lawsuits, including 2010’s ultimately unsuccessful 26-state lawsuit against the Affordable Care Act, were filed by Texas’s then–attorney general, Greg Abbott, who described his job like this: “I go into the office in the morning, I sue Barack Obama, and then I go home.”

There’s every reason to think the state’s current attorney general, Ken Paxton, will treat the Biden administration much the same way. And thanks to Trump’s nominees, the Fifth Circuit is more conservative than ever. When Trump took office, ten of the circuit’s seventeen slots had been filled by Republican presidents and five by Democratic presidents (including three by Obama). There were two vacancies. Because of the well-timed retirements of four Republican-appointed judges, Trump, with the help of Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell, managed to confirm six new judges to the Fifth Circuit, bringing the number of Republican-appointed judges to twelve out of seventeen.

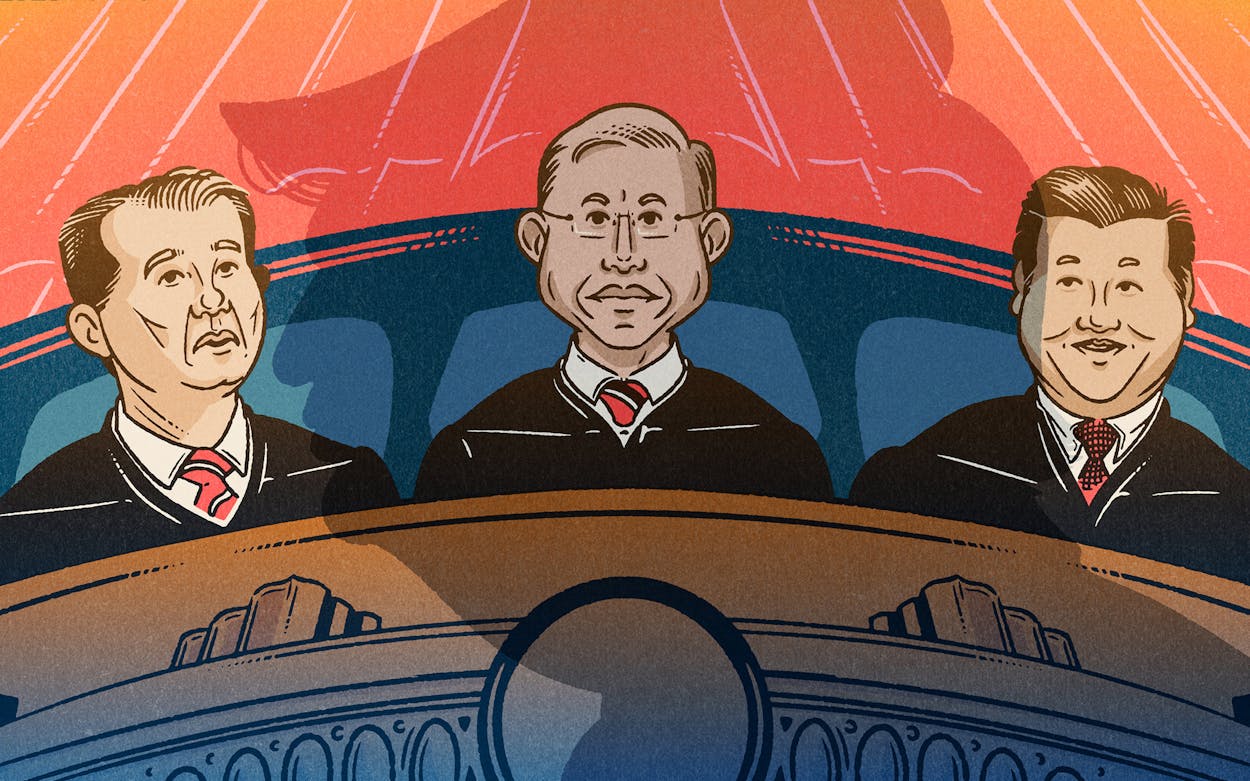

Three of Trump’s six Fifth Circuit picks—Ho, Oldham, and Willett—are from Texas. All three served under George W. Bush during his time as governor or president, as well as Greg Abbott during his tenure as attorney general or governor. And although Reagan appointee Edith Jones is still widely considered the most conservative judge on the court, Willett, Ho, and Oldham have staked out their places on its rightmost flank. “I do a lot of work with Texas conservative circles, and I think very highly of all of them,” said right-wing legal scholar Josh Blackman, who teaches at the South Texas College of Law, in Houston.

Dallas appellate lawyer David Coale, who argues regularly in front of the Fifth Circuit and donates to Democratic candidates, said Ho, Oldham, and Willett were “very conservative, by any measure. And they’re all relatively young, which means they’ll be on the court for many, many years.”

What does it mean to be a conservative judge? Today, most associate conservative jurists with “originalism”—the idea championed by the late Supreme Court justice Antonin Scalia that the Constitution should be interpreted as it would have been at the time of its ratification. The strictest adherents of originalism, such as Justice Clarence Thomas, purport to believe in striking down any law that conflicts with the Constitution as originally written or amended, no matter how many precedents must be overturned. But that wasn’t always conservative legal orthodoxy. The late federal judge Robert Bork, a conservative legal hero who today is best remembered for having his Supreme Court nomination fail in the Senate, believed judges should exercise restraint by deferring to lawmakers as much as possible.

Sanford Levinson, a left-leaning professor of law and government at the University of Texas School of Law, observes that Bork believed the courts generally should “leave it up to the political process to make decisions about … contentious subjects.”

That’s a very different view than the one espoused by Ho, Oldham, and Willett. The 54-year-old Willett, in particular, has become associated with the concept of “judicial engagement,” which envisions a much more active—some would say activist—role for judges. The best example of this is an opinion Willett wrote in 2015, when he served on the Texas Supreme Court. In Patel v. Texas Department of Licensing & Regulation, a majority of the court struck down a state law requiring eyebrow threaders to complete 750 hours of training to obtain a license, finding that the rule violated the Texas Constitution’s “due course of law” provision because a substantial portion of the training was unrelated to health and safety concerns.

But in his concurring opinion, Willett was much more expansive, waxing rhapsodic on the subject of economic liberty. “This case is fundamentally about the American Dream and the unalienable human right to pursue happiness without curtsying to government on bended knee,” he wrote. Willett even took aim at Supreme Court chief justice John Roberts’s famous baseball analogy. “Some observers liken judges to baseball umpires, calling legal balls and strikes, but when it comes to restrictive licensing laws, just how generous is the constitutional strike zone?” Willett asked. “Must courts rubber-stamp even the most nonsensical encroachments on occupational freedom?”

Willett’s concurrence won rave reviews in certain conservative legal circles, and may have helped earn him his seat on the Fifth Circuit. “Is This the Most Libertarian Legal Opinion Ever Written?” gushed Reason magazine. Previously, Willett had been best known for his prolific tweeting; overnight, he became a libertarian icon for his willingness to strike down laws purportedly infringing upon economic freedom. On the Fifth Circuit, he has continued pursuing his agenda of judicial engagement, ruling in Collins v. Mnuchin (2018) that the president can, without cause, fire the head of the formerly independent Federal Housing Finance Agency, established by Congress during the 2008 financial crisis to prop up the U.S. mortgage market. Willett, joined by the five other Trump appointees, went even further in a partial dissent, arguing that the entire agency was unconstitutional. Critics cite the decision as evidence that Willett and the other Trump-appointed judges are “trying to repeal the New Deal.”

Though Willett’s primary area of concern appears to be economic liberty, James Ho, 47, has attracted the most attention for his cultural conservatism and his role in the war on terror. During his Senate confirmation hearing, Ho, a Taiwanese-born immigrant and naturalized American citizen, faced questions about his time in the George W. Bush administration’s Office of Legal Counsel, where he worked on the infamous 2002 “Bybee memo” authorizing the use of torture against detainees. Since joining the Fifth Circuit, Ho has ruled against restrictions on campaign contributions and firearms, while supporting restrictions on abortion, which he has called a “moral tragedy.” In 2019, when the Fifth Circuit ruled that a wrongful death lawsuit against police officers in Kaufman County could proceed, Ho issued a scathing dissent defending the police. “If we want to stop mass shootings,” he wrote in the first line, “we should stop punishing police officers who put their lives on the line to prevent them.”

Andrew Oldham, 42, is the most recent Texan to have been placed on the Fifth Circuit by Trump. Like Willett and Ho, Oldham served under George W. Bush and Abbott, working in the Bush administration’s Office of Legal Counsel before moving to Texas in 2012 to serve as deputy solicitor general under then–attorney general Abbott. When Abbott ascended to the Governor’s Mansion in 2015, he brought Oldham along, installing him in the office of general counsel, where he rose to the top position before his 2018 nomination to the Fifth Circuit. Oldham came under fire during his Senate hearing when he declined to say whether Brown v. Board of Education, which ended school segregation, was correctly decided. (He did allow that the ruling “corrected an egregious legal error.”) Partly as a result, his confirmation vote was the narrowest of the three Texas judges at 50–49.

Among the major cases heard by the court since Oldham joined it was an October lawsuit over whether Texas election officials were obliged to notify voters whose ballots were rejected because of a signature mismatch. According to the lawsuit, more than five thousand Texas voters had their ballots rejected during the 2016 and 2018 elections because of signatures that were alleged to be mismatched; under Texas law, those voters didn’t have to be notified until ten days after the election, too late for them to prove their ballots were legitimate. Oldham was part of a three-judge panel that ruled the voters need not be notified, and that the signature-checking was necessary to prevent voter fraud. “Texas’s strong interest in safeguarding the integrity of its elections from voter fraud outweighs any burden the state’s voting procedures place on the right to vote,” the ruling stated.

Since circuit court appointments are for life, we’ll likely be hearing about Ho, Oldham, and Willett for decades to come. Had Trump won a second term, he might even have nominated one of them to the Supreme Court—Willett and Ho were included on Trump’s announced lists of potential Supreme Court picks. Under the Biden administration, we can expect further shakeups, said Blackman, the conservative legal scholar. “There are going to be a lot of Democratic judges who will decide to retire” so that they can be replaced by a Democratic president, he predicted.

Thanks to the confirmation of Justice Amy Coney Barrett, the Supreme Court now has a 6–3 conservative majority. If, as many observers expect, the court overturns or guts Roe v. Wade, it wouldn’t be a surprise if it did so by hearing an abortion case appealed from the Fifth Circuit. The same goes for the constitutionality of DACA, the Obama executive action that allowed young undocumented immigrants to remain in the United States, and whether the census must count undocumented immigrants. Ho, Oldham, and Willett are in the front ranks of an activist conservative legal revolution now poised on the threshold of victory. How far they decide to push that revolution, and whether they harbor any doubts about its consequences, will become evident in the years, and decades, to come.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy