Late on a muggy Friday night in July 1993, 25-year-old Edward Ates sat at the kitchen table of his grandmother’s house, talking with her about the dead woman next door. Ed’s brother, Kelvin, was there too, along with a friend. They lived in rural New Chapel Hill, just east of Tyler. That evening had been a terrible one. A few hours earlier, Ed’s grandmother Maggie Dews had discovered the body of a neighbor, Elnora Griffin, in her trailer. Griffin was naked and facedown on the floor, her throat slit to the bone. An investigator would later say that she had almost been beheaded.

Ed hadn’t known Griffin very well. She was 47, a dainty, energetic woman who stood four feet four inches tall and barely weighed one hundred pounds. She had recently moved to tiny New Chapel Hill from Dallas; Ed had returned home from Oklahoma a few months earlier. Since then he’d made his living as a handyman and landscaper, taking care of several properties in the neighborhood, including Griffin’s. Sitting at the table, Ed recalled how he’d gone to her trailer the week before to see about clearing out a wasp’s nest in the back and had talked with her again just a day prior about doing some weed-trimming in the yard.

Earlier in the evening, the Ates brothers and their grandmother had been questioned by various deputies from the Smith County sheriff’s office, who, after analyzing the crime scene, concluded that Griffin had been killed the night before. The investigators took statements from them, as well as from other neighbors, drawn by the lights and sirens, but nobody seemed to know anything—until a deputy talked with a friend of Griffin’s named Cubia Jackson, who said that she’d called Griffin the previous night, between 9:30 and 10:30, and asked what she was doing.

“Well, I’m sitting here talking to Edward,” Griffin had said. Edward who? “Ms. Dews’s grandson.”

Now, sitting at the kitchen table, Ed heard a knock on the door. He opened it to find three deputies, led by Detective Dale Hukill, who said they had some more questions for Ed. Would he mind coming down to the sheriff’s office? Ed said he would go, but first he wanted to talk to his mother, Margie Jackson, who lived nearby and had just phoned to say she was headed over. Margie was a boisterous woman; addicted to cocaine, she had plenty of experience with local authorities. When she arrived, she insisted on accompanying her son.

They arrived at the sheriff’s office in Tyler around 11 p.m. Ed had been questioned by law enforcement before; indeed, he had spent time behind bars. He was by nature a calm person, and that evening he’d also had a few beers. Now he told the deputies he didn’t think he needed a lawyer, even after Hukill told him what Cubia had said. Ed denied being in Griffin’s trailer that night.

The deputies asked Ed to take off his shirt, and they checked him for scratches or blood; they checked his fingernails too, then asked him to take off his shoes. They found no blood, but when Hukill examined the sole of the left shoe, he noticed a trace of something stuck in its tread; he smelled it, then scraped it off and put it in a baggie. He told Ed he was doing this because deputies had found what they thought was feces in Griffin’s trailer, including a clump in the kitchen that appeared to have been stepped in. They believed she had probably been sexually assaulted or strangled, either of which could have led to her losing control of her bowels.

At some point Ed went to the restroom. He often carried a few Jolly Rancher candies in his pockets, and now he ate one and threw the wrapper in the garbage can. Back in the interrogation room, he again denied having been in Griffin’s trailer that night and said he’d been at the apartment of his girlfriend, Monica Bush. She had come by to pick him up between 9:30 and 10 p.m., he said, and they’d sat around talking for a few hours. Hukill dispatched a deputy to call Bush and check out the alibi, but Bush contradicted Ed, saying he’d shown up on his own. Armed with this, Hukill confronted Ed again, certain that almost everything coming out of his mouth was a lie.

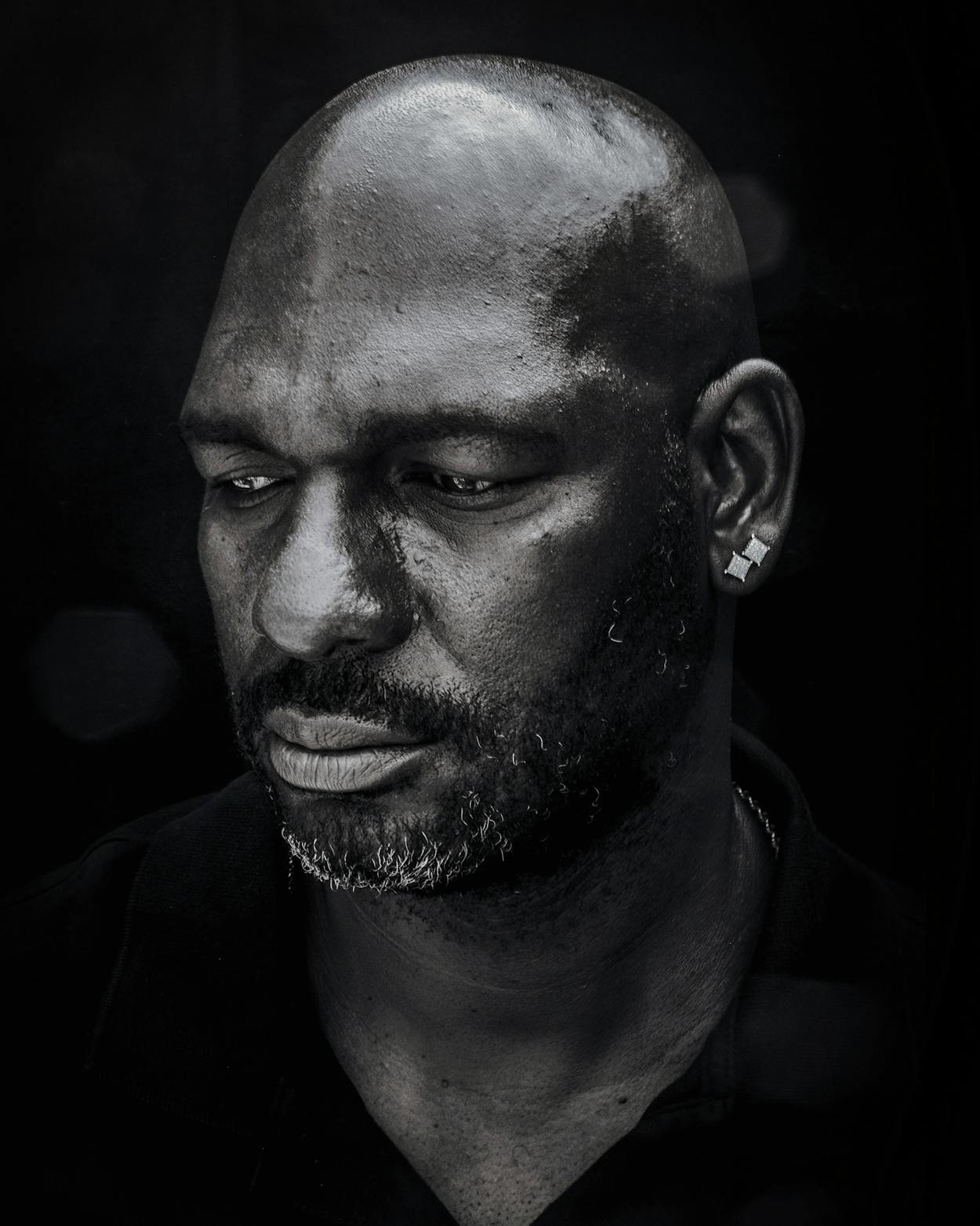

What he’d wanted to do was play basketball. Ed was a muscular six feet seven inches tall, and with his size and strength, he had dominated games at Chapel Hill High School and the outdoor courts where he and his friends played. “He was a beast,” remembered Kelvin. Ed idolized Michael Jordan—his grace as well as his confidence on the court—and even resembled him. He wore only Air Jordans and dreamed of getting a scholarship to Jordan’s alma mater, the University of North Carolina, then joining the NBA.

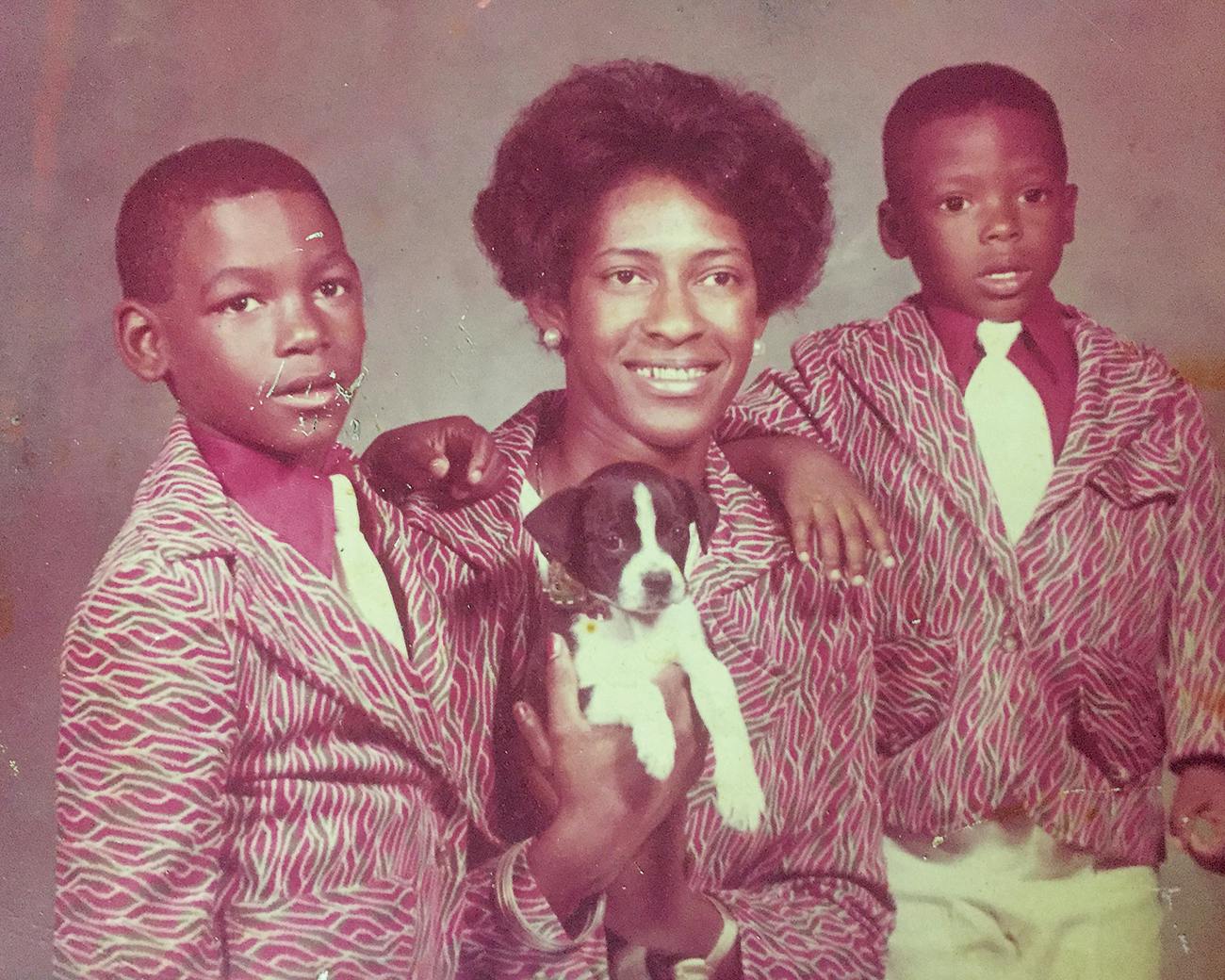

Ed’s parents had split up when he was young, and at first, he and Kelvin, two years younger, lived with their mom, who worked a variety of jobs in Tyler, including as a seamstress and solderer. But then she married a jealous and violent man who regularly beat her (Margie would later shoot him after he broke her jaw; he survived). He didn’t want Ed and Kelvin around, so they moved in with their father, Emerson, a reserved man who ran a nightclub (Margie had shot him once too).

While still in elementary school, the boys began spending more and more time in New Chapel Hill with Dews, Margie’s mom. Eventually they moved in, and Ed became close to her, helping her take care of her garden and cook large dinners for family gatherings. He and Kelvin loved living in the country, where the pine trees hugged the roads and the land sloped down into the brush and creek bottoms. They fished often in those creeks, and they started working at a young age for a nearby rancher who had a couple hundred cattle. By age fourteen, Ed was baling hay, grooming horses, and riding four-wheelers through the meadows looking for stray calves. He was a hands-on kid, stoic like his father; if there was a job that needed to be done, he could do it.

School, though, was another story. Ed wasn’t a good student and often got in trouble; he was suspended twice, once for fighting a white kid who called him a racial slur. He dropped out his senior year and joined the Gary Job Corps, a government job training program that took him to San Marcos. He returned to New Chapel Hill, got his GED, and played basketball in city leagues, entering tournaments and traveling to Houston, Dallas, and Austin. Sometimes he and his friends engaged in petty thievery—of candy or gasoline—and other times they bought new Nikes and Guess jeans from hustlers on the street.

It was past 1 a.m., and Hukill briefed Waller on his conversation with Ed. They began piecing together what they believed to be possible clues.

One afternoon at the courts, Ed’s old high school coach saw him and said that he could probably get a basketball scholarship at Western Oklahoma State College, in Altus, a small town in the southwestern part of that state. So in the fall of 1989 he drove to Oklahoma with two friends from Chapel Hill High who became his roommates.

Far from home, Ed soon found himself in trouble again. As they had done in Tyler, he and his two roommates would buy stolen Calvin Klein shirts as well as toilet paper and deodorant. One day that October, Ed and one of his roommates were busted for concealing stolen property. Ed was also charged with stealing from a clothing store that had, strangely enough, been set on fire. Ed was charged with arson. He admitted to possessing stolen clothes but denied everything else.

The local DA offered Ed’s lawyer a plea bargain: if Ed pleaded guilty to arson, burglary, and concealing stolen property, he would be sentenced to ten years but get out in two if he behaved himself. Ed mistakenly thought he was getting probation and took the deal. He was sent to a succession of reformatories and work camps, then was arrested again for trying to escape from one of them—another felony—though Ed insisted he and his fellow inmates had just gone across the street to play basketball. He finally wound up at a halfway house in Oklahoma City, from which he was released in the spring of 1993. He had spent almost four years in Oklahoma, most of them incarcerated. Now he had four felonies on his record.

After interviewing Ed, Detective Hukill returned to the crime scene, where homicide detective Jason Waller and other deputies had been collecting hair, blood, and cigarette butts. It was past 1 a.m., and Hukill briefed Waller on his conversation with Ed. They began piecing together what they believed to be possible clues. There was a Jolly Rancher candy wrapper in Griffin’s bathroom garbage can. A pink bath towel was covering her front door window, and they discovered a large handprint on it, as if a big man had hung it there. Griffin’s white Mercury hatchback was parked closer to the trailer than a neighbor said she usually parked it, as if someone else had left it there. Inside the car, deputies found, the seat had been pushed all the way back, as if it had been driven by a tall man. The radio station was tuned to KZEY, which played rap music; Griffin, a religious woman, listened to gospel.

Later that Saturday, Hukill and Waller were joined at the crime scene by a man named David Dobbs, the first assistant in the Smith County district attorney’s office and a rising star there. A boyish 31-year-old with curly, dirty-blond hair and piercing, pale green eyes, he would actively work with the deputies in the investigation, meeting Hukill at Bush’s apartment complex, where they found two men who said they recognized Griffin’s car from a photo and said it had been parked there the night she was killed. Ed, Hukill wrote later, must have driven it there.

At least initially, Hukill had another suspect too, a man named Leonard Moseley, who’d been romantically involved with Griffin but lived with a woman, Angela Walker, with whom he’d had a baby. Moseley still saw Griffin for a regular late-night Thursday date, but he told Hukill he’d been at work on the night of the murder, then gone home. Walker backed up his alibi. During an interview with Moseley four days after the body was found, Hukill said he believed him. “I’ve got one particular person who told me where he was, what he was doing, and his story ain’t checking out,” the deputy told Moseley. “I don’t think you did it. I really don’t. Not at this point, especially because this other boy, this other thing is just, like, slapping us in the face right now.”

That particular person was Ed, who was arrested on August 26 and charged with murder. A Tyler newspaper noted that Smith County had had seven murders so far in 1993, and arrests had now been made in each of them. Sitting in jail, Ed was confident that he wouldn’t actually be tried for the crime and felt all the more sure when investigators concluded their blood-typing, fingerprinting, and hair analyses. No physical evidence tied him to the scene. By contrast, though the medical examiner found that Griffin had in fact not been sexually assaulted, the second suspect, Moseley, couldn’t be ruled out by blood type as a “possible donor” of a semen stain found on a comforter. One of Ed’s court-appointed lawyers, Clifton Roberson, told him that the state didn’t have a case. Ed rejected a plea bargain of forty years.

Judges and DAs in conservative Tyler were elected on promises to wage war on crime. Prosecutors plowed through cases, and they were particularly relentless with murders.

It took Ed’s family another eight months to get him out on bond, but once free, he felt like his life might actually be turning around. He enrolled in trucking school—he liked the freedom of the road—and upon graduation got a job with a Tyler waste-management company. He bought himself a new pickup. And in October 1994 he went to a Halloween party and met a pretty young woman from Dallas named Kim Miller. Ed liked her immediately: she was smart and independent, a sociology student at the University of Texas at Tyler. In turn, Kim thought the soft-spoken basketball player looked a lot like Michael Jordan. The day after the party, he called her seven times.

She thought he was joking when he said he had been indicted for murder. Ed would forget about it sometimes himself, especially since his trial date kept getting pushed back (both the prosecutors and the defense lawyers, busy with other murder cases, asked for postponements). The couple dated for a few months, and Kim got pregnant. She graduated in May 1995, and in October their daughter, Kyra, was born. Ed loved holding her before heading out to drive his truck. Kim eventually convinced him to move to Dallas, where her parents lived and where there were more opportunities for a college graduate.

Ed landed a job driving a garbage truck. Meanwhile he was getting more and more notices to appear in court. He talked to his boss about taking some time off, and in July 1996 Ed went on trial for murder.

For years, Smith County had been one of the most stringently law-and-order communities in Texas. Judges and DAs in conservative Tyler were elected on promises to wage war on crime, which meant punishing those they thought were guilty, protecting victims, and keeping the streets safe. Prosecutors plowed through cases, and they were particularly relentless with murders. In one notable example, beginning in 1978, they tried Tyler-area resident Kerry Max Cook three times for the same murder over the course of sixteen years; one attempt ended in a mistrial, the other two in guilty verdicts that were thrown out by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals.

Even without any physical evidence tying Ed to the scene, prosecutors felt they had a good case, especially with the charismatic Dobbs at the helm. One of Ed’s lawyers, Tom McClain, had worked in the DA’s office with Dobbs and knew what he was up against. “Dobbs tried a case as hard as anyone I’ve ever seen,” said McClain. “And he’s really smart.”

At trial, Dobbs theorized that Ed killed Griffin, stepped in her feces, drove her car to his girlfriend’s, and returned home after midnight. The state offered no motive and indeed no proof that the debris on the bottom of Ed’s shoe or the clumps in her trailer were human feces. An FBI expert could determine only that the smudge on Ed’s shoe was “protein of human origin,” which could have been anything from sweat to spit. Although Ed had been in trouble with the law—besides his trouble in Oklahoma, he’d also been busted several times in Tyler for misdemeanor theft as well as for forging a check—he had no history of violence. The jury, which included two African Americans, couldn’t reach a unanimous decision and after two days was deadlocked at 8 to 4 for guilt. Finally, on the third day, Judge Louis Gohmert declared a mistrial.

Ed thought that he had finally put his troubles in Smith County behind him. He asked Kim to marry him on Christmas Day. At their wedding the following April, Ed, a towering figure in a white tuxedo, danced with Kim to “For You I Will,” a soaring love ballad. “I will stand beside you,” sang R&B star Monica, “right or wrong.”

Yet one hundred miles away in Tyler, the DA’s office was working in earnest to try him again. After the mistrial, Gohmert had scheduled a hearing for a second trial, and investigators, hoping to find Ed’s DNA profile at the crime scene, had conducted DNA testing for the first time on some crime scene hairs. None, though, proved to belong to him. Then, two weeks after Ed’s wedding, on a day he was supposed to appear in Gohmert’s courtroom for another pretrial hearing, he was instead waiting in the Dallas County jail, having been mistakenly arrested on a warrant for one of the old Smith County misdemeanor theft cases that had already been disposed of. Gohmert revoked Ed’s bond and had him transferred to Tyler and put behind bars.

Sitting in a crowded cell, Ed met a man named Kenneth Snow, an ex-con and professional boxer who was charged with two robberies, including one in which he was accused of beating up a man. Snow had once been a contender for the middleweight crown, and he still had dreams of climbing back into the ring. The two jailmates became friends, playing Spades and sharing the Kools that Ed’s grandmother had bought him. After Ed bonded out, Snow, still in jail, would even call him at home. By then Ed and Kim had purchased a small brick house in a new subdivision in southeast Dallas.

When Ed went on trial again, in August 1998, his lawyers still thought the state didn’t have much of a case. Kim, five months pregnant with their second child, initially didn’t even join Ed in Tyler, but when he told her there were no black jurors (Dobbs had struck six African Americans from the jury pool, in a city where one in four people were black), she became worried. She took time off from work, left Kyra with her parents, and drove to the Tyler courthouse. This time prosecutors had a secret weapon: Ed’s new friend Kenny Snow, who was still awaiting trial for the robberies. Ed stared in disbelief as Snow, who had a reputation as a snitch, testified that Ed had tried to get him to lie on the stand and point the finger at someone else. Snow swore that Ed had paid him to tell authorities that he’d overheard another inmate, a man named Frances Johnson (an acquaintance of Ed’s who had dated Griffin), confess to attacking her. Snow said Ed had even written out a script for Snow. “He gave it to me to memorize it,” Snow testified. Instead, Snow sent the script to the DA, and a handwriting expert verified that it was written by Ed. On the witness stand, Snow denied that he’d been promised anything by prosecutors for his testimony.

Although the state couldn’t put Ed at the crime scene forensically, Dobbs and a fellow assistant DA presented Ed’s lie about his alibi and investigators’ observations regarding the handprint on the towel, the position of the car seat, and the candy wrappers. The prosecutors hit Ed hardest when it came to the alleged feces. Despite the FBI agent’s conclusion that the smudge on Ed’s shoe was merely “protein of human origin,” Dobbs used the term “human feces” six times in closing arguments alone. “Liar sitting over there with human feces on his shoe and no explanation for it,” he declared.

Ed’s lawyers tried to show that Snow was an untrustworthy jailhouse snitch, making him read a letter he had written Dobbs from jail. “I think I could be the best informant that ever come out of Tyler, Texas,” he’d proclaimed. They emphasized that none of the hundred-plus hairs, blood, semen, fingerprints, or cigarette butts tied Ed to the crime scene—they also pointed out that he had no scratches or blood on him or any motive to kill Griffin. Moseley was a much better suspect, they said. Again, the jury took a long time and was deadlocked 10 to 2 after two days, in favor of guilt. Again, Ed was offered a plea bargain, and again he turned it down. But on the morning of the third day, August 13, 1998, the two holdouts changed their minds, and the jury found Ed guilty. According to a local paper, when the verdict was read, “A cry went up” from Ed. He was sentenced to 99 years. Kim, weeping, watched as her husband was handcuffed and taken away.

At the H. H. Coffield Unit, near the town of Tennessee Colony, Ed spent much of his free time doing what he did best: playing basketball. One day a friend confronted him. “All you do is play basketball,” he said. “Get your ass up—we’re going to the law library.” His friend showed Ed how to search for his case, and in mid-2000, Ed saw that his appeal had been denied earlier that year. He began spending every day in the library, researching, and after Texas passed a law giving inmates the right to petition for DNA testing of evidence, Ed did so, asking that everything at the crime scene be tested, not just the hairs.

He fell into a routine, getting up at 5 a.m., working on a road crew. Later he served as a cook and a groundskeeper. He learned to keep his emotions in check, to not show any weakness. He avoided trouble and developed a reputation for toughness on the prison basketball courts, living up to his new nickname: Big E.

Back in Dallas, Kim was struggling to raise Kyra and the new baby, Zach, by herself. She sold their home and moved in with her parents and would bring Kyra and Zach to visit their dad every two weeks. On the long drive to Tennessee Colony, she would tell them how their dad was in prison for something he didn’t do. When they arrived at the prison, the kids toddled to Ed, who got to hold them for an hour or two. But it crushed him when he had to return to his cell. The kids didn’t understand why their father couldn’t come home with them, and as the years crept by, the visits became harder for all of them. Zach, especially, started getting resentful. Like his father, Zach was passionate about basketball, playing every day. But unlike his friends’ dads, Ed never came to his games or his birthday parties. “When are you coming home?” he would ask over and over. Kim finally stopped talking about Daddy—it was too sensitive a topic—which made her even more depressed.

The kids didn’t understand why their father couldn’t come home with them, and as the years crept by, the visits became harder for all of them.

Kelvin visited Ed for a while too but couldn’t bear to hear his brother called “convict.” He hated seeing the grimace on Ed’s face when he would head back to his cell after a visit. So Kelvin stopped making the trip.

Ed never heard from the attorney assigned to him for his DNA claim, and in 2006 his grandmother hired two Houston lawyers, father and son Randy and Josh Schaffer. Randy had a long history of freeing the wrongly convicted, and to him, Ed’s case had all the earmarks of a bad conviction: an entirely circumstantial case, no DNA, no eyewitnesses, no confession. What had sent Ed to prison, it seemed to the Schaffers, was Snow’s testimony.

And now the lawyers had a secret weapon of their own. Snow had been released from jail three months after Ed’s trial, but he eventually fled the state and was arrested for violating his probation and brought back; in 2004 he was sentenced to forty years. While in prison, Snow got a message to Ed’s new lawyers: he had lied on the stand.

Snow’s betrayal of Ed, as he swore in an affidavit, was especially treacherous. Snow said that, while in jail, he had overheard a conversation between Ed and Frances Johnson, the man who’d dated Griffin, in which Johnson admitted to being in her trailer the night of her murder. Johnson said he grabbed a knife and “wore her ass out.” Ed asked Snow to help him out, and Snow agreed to recount the conversation to Ed’s lawyers, who then informed the trial judge about the new witness at a pretrial hearing. But two weeks later, Snow claimed in the affidavit, prosecutor Dobbs visited him in jail. “Dobbs told me that if I testified for Ates, the state would not help me with my cases,” Snow said. “They told me that I would never box again unless I helped them convict Ates.”

After Ed was convicted, Snow pleaded guilty and was given ten years’ probation—even though with his record he would have likely received 25 years to life in law-and-order Smith County. (Indeed, the judge told him she had never granted probation in a case like his, “where there is violence and kind of an anger that is of some concern to me.”)

This, Josh Schaffer thought, was a classic case of a favorable deal with a jailhouse snitch that was hidden from defense lawyers, violating a long-established constitutional rule that the prosecution must disclose everything that is favorable to the defendant, including evidence that demonstrated that a witness might not be credible or honest. In 2010 Josh filed a writ of habeas corpus—an appeal asserting a constitutional violation—with affidavits from Snow and his lawyer. Tyler judge Kerry Russell ordered a hearing. Ed was as optimistic as he had been in years. Kim showed up for the hearing, along with their children and her parents; all of them thought this was the answer to their prayers.

At the hearing, lawyers battled over whether prosecutors had promised Snow a lighter sentence in exchange for his testimony against Ed. Snow’s attorney testified that there had been just such a deal, even if it wasn’t in writing and hadn’t been called a plea bargain: a violent habitual offender had received probation in Smith County after testifying for the prosecution, so, logically, some kind of agreement had been made. Dobbs maintained that there hadn’t been any kind of deal—not even a gentleman’s agreement—and denied everything else Snow had said.

To Ed’s shock, Judge Russell sided with the state, finding “no credible evidence that the State had any agreement, unwritten or otherwise” and turning down his writ.

Ed had one more shot. All around him at the Coffield Unit, men were being freed by post-conviction DNA testing. Ed felt certain that if all of the evidence in his case were tested, he would be exonerated. Though he had never received any help when he had asked for it before, he tried again, filing another motion for DNA testing with the court.

Once again, he got no response. The months drifted into years, and Ed fell deeper into a pit of despair, angry at everybody. Every single thing that could have gone wrong in his life had gone wrong, he thought. He finally resigned himself to spending the rest of his days in prison. He wrote Kim and told her that maybe it was time she divorced him and moved on with her life. Bring the kids every once in a while, he asked, and make sure they see his mom and grandmother.

Big E had shifted into survival mode, cutting off all hope. Only in his cell, behind an iron door, was he still Ed. He’d lie in the darkness and dream of his family: Kim, Kyra, and the son he barely knew.

A thousand miles to the north, in rural southwestern Michigan, a tall, bearded fireman named Bob Ruff had troubles of his own. His marriage had fallen apart, and he was fighting for custody of his two kids. In his downtime, Ruff, 32, began listening to a comedy podcast, whose host would eventually recommend a true-crime podcast called Serial, a deep dive into a flawed murder investigation. In the fall of 2014, Serial had become one of the most popular podcasts ever, and Ruff decided to check it out. He loved the show and soon became obsessed with it, listening to episodes over and over, taking notes. He decided to start his own podcast, called The Serial Dynasty, and recorded it in a garden shed behind his house. It was, he would say, like a book club for Serial fanatics. Ruff was fascinated with the whole idea of solving crimes, and he invited listeners to email their theories. He also interviewed a former FBI profiler and a false confessions expert about the case. Ruff, who has a loud, resonant voice, was not a nuanced host; he didn’t use a script, just notes, and the result was emotional and fiery. He began picking up thousands of new listeners drawn by his passionate observations. After episodes, fans would visit his Facebook page and chime in.

“I believe you’re an innocent man,” Ruff told him. Finally, Ed began to tell Ruff his story.

In October 2015 Ruff renamed his podcast Truth & Justice, set up a GoFundMe account, and raised enough money for an actual studio. Soon he had more than 100,000 subscribers, whom he called the Truth & Justice Army. With a boom in true-crime podcasting, Ruff decided to change careers. He quit his job and became a full-time podcaster, selling ads to pay his salary. By then he had two new tattoos, large ones on his forearms: on his left, “Veritas,” Latin for “truth”; on his right, “Aequitas,” for “justice.” Now he just needed a case to investigate, and one of his listeners emailed about her uncle in Texas, a former boxer whom she said had been falsely convicted of two robberies.

His name: Kenneth Snow.

Ruff began investigating and thought there might be something to the case, so he traveled to Tyler to get court documents. He also spoke by phone to Snow, who told him he’d been released back in 1998 after he had testified at the trial of a man named Ed Ates. Snow claimed that, earlier that year, Dobbs and an FBI agent had visited him in jail and told him they were going to put him in a cell with Ed. If Snow didn’t get a confession, he’d get 99 years for the robberies; if he helped, he’d get probation. So Snow helped. Snow couldn’t be certain that Ed was innocent, he told Ruff, but he reaffirmed what he’d said in the affidavit: that he’d heard Frances Johnson say that he attacked Griffin.

Ruff soon found his enthusiasm for Snow’s case dimming. Some of the things the inmate told him didn’t pan out, others couldn’t be checked, and ultimately there wasn’t a lot Ruff could do for Snow, who had pleaded guilty.

But Ed was another matter. In January 2016, Ruff, still searching for a worthy case, sent him a letter. “My name is Bob Ruff,” he wrote. “I have a podcast, and I think I can help you.”

By this point Big E was almost completely isolated from the free world. He’d had half his life taken—and all of his family. His father had died early in Ed’s time in prison, his grandmother had followed in 2014, and he hadn’t talked with his mother or his brother in a couple of years. Ever since Ed had urged Kim to divorce him, she had retreated from him as well. She had stopped writing letters and gone ahead and filed divorce papers. She visited only once a year, on Father’s Day, bringing Kyra. Zach, by then a moody adolescent, had ceased coming altogether.

Ed had been scammed once before by someone who offered to help get him out of prison, and he didn’t trust anyone on the outside anyway. He threw Ruff’s letter into the trash.

Ruff mailed Ed another letter saying he just wanted to talk, and he put money in Ed’s commissary account so the inmate could phone him. Ed called but nervously hung up before Ruff could answer. Then he called back. “I believe you’re an innocent man,” Ruff told him. Finally, Ed began to tell Ruff his story.

Ruff liked Ed immediately. He spoke with an East Texas drawl and was laid-back and restrained, carefully keeping his anger in check. The two chatted again a week later, and Ruff recorded the conversation. In the next episode of Ruff’s podcast, titled “Hope,” he played the interview, immediately followed by Adele’s heart-tugging ballad “Hello,” performed by a Zimbabwean singer. Then listeners heard a conversation Ruff had had with Snow. “I would like to tell Mr. Ates that I’m sorry for what happened,” Snow said. “If I can help in any way I can, I will be at peace with myself.” Ruff alternated the soaring, sentimental music with the apology. It was maudlin, over-the-top. Listeners loved it.

Soon Ed was calling Ruff every Tuesday morning at ten, giving more details of his life and his time in prison. He began to feel comfortable enough to reveal his festering anger. “Fuck Kenny Snow!” he’d say when Ruff brought him up. “David Dobbs can go to hell!” An energized Ruff contacted Mike Ware, the executive director of the Innocence Project of Texas. Ware said he’d be happy to look into Ed’s case but that he needed trial transcripts. So in April, Ruff returned to Tyler, armed with a portable scanner given to him by a listener. It took him five days to make copies of 27 volumes. He shared many of the documents, as well as crime scene photos, on his website.

He made more trips to Texas, learning the basics of the criminal justice system and researching other wrongful conviction cases from Smith County, including that of Kerry Max Cook, the Tyler man tried multiple times for murder, who spent almost twenty years on death row before being freed, in 1997. The more Ruff researched, the more he learned about Ed, this supposedly brutal killer. For example, Chris Scott, a fellow inmate who was later exonerated, told Ruff, “He’s friendly, he don’t want to fight nobody, he don’t want to be a part of nothing physical.”

Ruff was basically crowdsourcing an investigation—“Two hundred thousand minds are better than one,” he said in an episode—and doing so in real time, week after week, asking listeners for help. He did this by posting on Twitter and Facebook, where the podcast fan page had 6,500 active users leaving 20,000 comments a week. A serologist examined data from a 1993 report on blood found under Griffin’s fingernails and said she thought there were two different types. Amateur photo enthusiasts tried to discern a footprint in the alleged feces clump in the kitchen. When Ruff needed help figuring out who had a certain unlisted phone number, a listener volunteered to go to the Kilgore city library and pore over old phone directories.

Ed explained to Ruff two of his case’s biggest mysteries. Yes, he had lied about how he got to Bush’s apartment: he had taken his grandmother’s car that night to visit his girlfriend, something he wasn’t supposed to do and didn’t want his mother (who was sitting next to him in his interview) to know. Ed wasn’t scared of the deputies or worried what they would think, since he had nothing to do with the murder. He was scared of his mom, a cocaine addict who had shot her two former husbands—and would later, during a drug-fueled argument, shoot Kelvin in both legs. Also, Ed told Ruff that the “script” Snow testified about was actually a page of notes Ed had written to send to his lawyers after his conversation with Johnson. It later vanished from the cell, and he eventually figured out that Snow had taken it.

Ruff relentlessly attacked the state’s case. He described how Hukill had homed in on Ed from the start, while failing to follow up on other suspects. In addition to Moseley, Griffin had been dating Johnson and a third man, and neither was ever interviewed. Hukill never checked Moseley for scratches or blood, as he did Ed. Waller and the other investigators never measured the large handprint on the towel. No one ever photographed the position of the car seat. Though the car radio was tuned to KZEY, which played hip-hop, the station also played gospel music.

Ruff became increasingly incensed about the Smith County criminal justice system. He recorded several episodes on Cook’s case and implied that Dobbs (who had also prosecuted Cook) was a psychopath. “I will not rest until you are behind bars for your crimes against humanity,” Ruff intoned. He suggested that Hukill and Waller weren’t just incompetent—they had framed Ed. “The Smith County justice system has destroyed countless lives,” he thundered.

In May 2016 the Innocence Project of Texas agreed to take the case, and Ed got a new lawyer, Allison Clayton, who began visiting and writing him. Usually the lawyers at IPTX have to spend hundreds of hours doing tedious legwork—getting transcripts, doing interviews, asking experts how a test works, checking out possible leads—but Ruff and his army had already done much of it. IPTX also typically has to scrape together funding for its investigations, but the army helped there too. When Ruff put out a request for help to pay for possible DNA testing, listeners ponied up $7,000. So many of IPTX’s clients were lost in the prison system. Though Ed had once been forgotten himself, he was now one of the lucky few.

While Ruff was investigating Ed’s case, he also got in touch with Kim, who by then hadn’t seen or spoken with her husband in a year. Like Ed, she was initially skeptical. She had no idea what a podcast was, but when Ruff told her, “I believe your husband is innocent,” she burst into tears. This was the first time she’d heard anyone outside her family and Ed’s lawyers say that.

For years Kim had been imprisoned in her own dark place, raising two kids while working full-time. She never thought her husband was guilty; he was a gentle giant, she’d say. She wished he would smile more, but he was no killer. In some ways she loved him now more than ever—he was the father of her children, and her whole life was built around Kyra and Zach. But she also thought he was never coming home. Kim, who smiles easily, rarely told anyone of her inner struggles. Sometimes the despair would get so heavy that she would steal away to the restroom at work to cry in one of the stalls.

Kim felt terrible about not visiting, even though he had urged her to stay away. Her first question to her husband was “Can you forgive me?” Of course, Ed replied.

She had tried to move on, and even though she had filed divorce papers, because of an error, she hadn’t received a notice to appear in court. She could have followed through to nail down a court date, but she never did.

Now she thought God had been guiding her hand all along. A week after Ruff called, she went to visit Ed and found a different man. He was no longer alone in his fight; besides talking with Ruff every week, he had been getting letters from the podcast’s listeners, sometimes as many as ten a day. And he was really happy to see her. She felt terrible about not visiting, even though he had urged her to stay away. Her first question to her husband was “Can you forgive me?” Of course, Ed replied. He wanted his family back.

They began talking more, and they broached the concept of his actually coming home one day, which until then they hadn’t allowed themselves to even imagine. “What do you want to do?” Kim asked. “I just want to go to work, come home, sit on the couch, and be with my family,” Ed answered. He started making lists of resolutions, just in case he ever got out:

Stop using cuss words.

Smile.

Get my driver’s license.

Take care of my wife and kids.

Have a conversation with my son and daughter, make sure they aren’t upset at me.

Tell my family I love them.

At night Ed would pull out his lists and go over them, memorizing and planning. After a summer visit from Kim, Ed told Ruff he hadn’t felt so good in years. Though deep down he was still angry—sometimes he would gripe to Kim when she said, “I know what you’re going through”—he was tired of being that way. He wanted to change.

Ed had gone up for parole twice but was denied both times. To be released, an inmate must usually show remorse for his crime and take responsibility for it, but Ed wouldn’t cop to something he didn’t do. He became eligible again in March 2018, and Ruff and Clayton set out to make sure this time would be different.

Ruff asked listeners to send letters, and they flooded him with hundreds. He winnowed the stack to fifty and sent them to Clayton, who passed them on to the Board of Pardons and Paroles. Ruff sent his own letter about Ed, as did Kim. “After twenty years apart, I still love my husband, and I’ve built a home for him to come home to,” she wrote. “The kids and I want him here, and we will support and encourage him every step of the way.”

Ultimately, Ed needed the approval of two out of three commissioners in the parole board office in nearby Palestine. Clayton asked for help from experienced parole lawyer Roger Nichols, who, working pro bono, presented the case to one of the commissioners on March 27. Another commissioner interviewed Ed the next day. Toward the end of that meeting, Ed would later recall, the man said, “What I’m getting is, you didn’t do this.” Usually it takes two to three weeks for the board to make their decision public, but Ed was granted parole the next day. When Clayton heard, she immediately called Kim, who was at work. “Ed made parole,” she said through tears. Kim had to excuse herself and walk outside, where she started crying and hollering, “I knew he was coming home!”

On a muggy morning in early September 2018, Kim drove her kids to Huntsville, where Ed had been transferred prior to his release from prison. She wished she could’ve brought Margie too, but Ed’s mother, suffering from Alzheimer’s, had killed herself the previous summer. By the time the Ates family arrived, there was a crowd of fifty people standing vigil, waiting for Ed. Many were women from East Texas, though one had traveled from California, another from Arkansas. Most of them were strangers, but they had seen one another’s photos on the Truth & Justice Facebook fan page. They couldn’t believe that Ed was getting out—and that they were going to witness it. A few carried hand-lettered posters that read “We stand with Ed” and “Welcome home, Ed. Love, the T & J Army.”

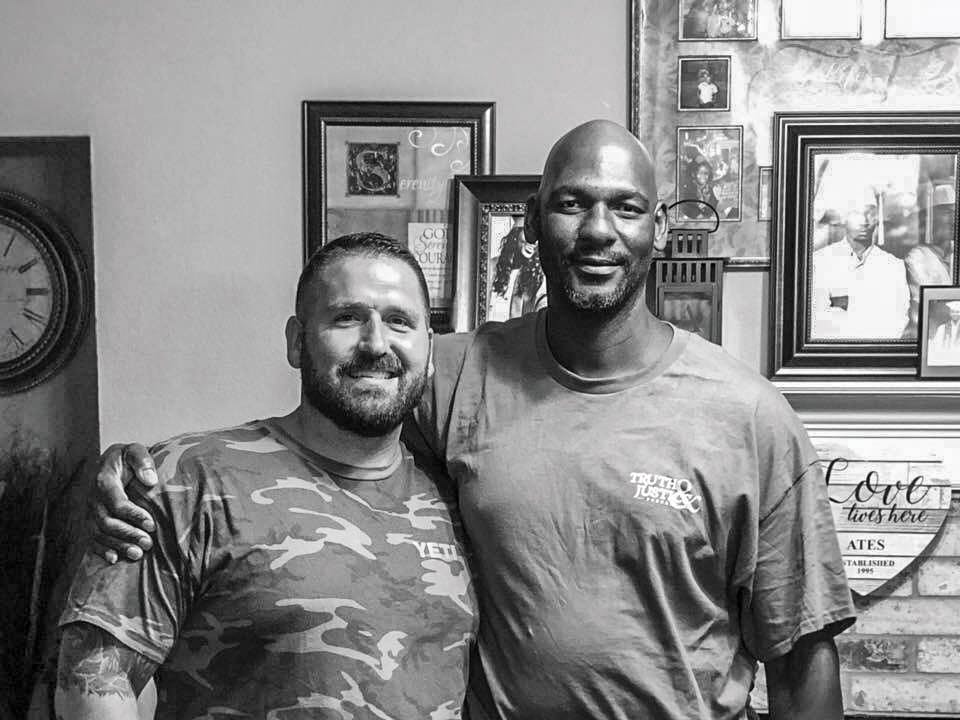

Ruff was there, and he greeted Kim, Kyra, and Zach with hugs and tears. This was a huge day for Ruff, the end of a remarkable campaign. Podcasts had barely existed ten years before, and Ruff knew, as did everyone else in the crowd, that Ed would still be stuck behind bars if Ruff hadn’t started one and found an army of followers. Like a few other podcasts—Serial, Empire on Blood, In the Dark—his had successfully drawn attention to a questionable conviction and actually helped free someone. In addition, Ruff had raised more than $35,000 from listeners to help Ed get back on his feet.

Kim looked around at the crowd. “I don’t think he’s ready for this,” she said. More than anything, she was concerned about how her reserved husband would deal with the world—in particular his family. She was desperate for him to feel at home. “You have to communicate with us,” she had told Ed. “Especially me.” She knew she could be pushy, but that was the only way her family had survived for this long. She also knew Ed was still angry and that she would have to help guide him, to find a way to not let his bitterness consume him.

Kim watched her kids talk to members of the crowd. Kyra, 23, is like her mother, expressive and quick with a hug, and was laughing with total strangers. Zach, three years younger, is like Ed, reserved and stoic. He stood alone, nervous about reuniting with his father, whom he had never seen outside prison walls.

Finally, a little past noon, someone called out, “I think I just heard the gate open,” and everyone stood up and looked across the street. A tall, bald man was walking down the sidewalk. A few people cheered. Ed, wearing a large plaid shirt, baggy pants, and black Crocs, ambled across the street, some yellow envelopes in his right hand, his left arm swinging wildly. His head shone in the sun.

He looked nervous, and as he hit the other side, Zach emerged from the crowd and walked toward his father. Ed seemed about to shake his son’s hand, but Zach opened his arms, and the two men fell into each other, son burying his head in his father’s shoulder. The crowd sniffled in the heat. “Don’t leave me again,” whispered Zach. “I won’t,” his dad responded. When Ed unwound himself from Zach, he went to Kim and held her for a long time. Then he hugged Kyra, who was crying openly.

After that, Ruff approached. “Hey, brother,” he said, and the two men embraced. He was followed by a succession of pen pals and total strangers. Ed, who wore a half smile, seemed happy but overwhelmed. “I love you, sweetheart,” said one as she hugged him. “I’ve been praying for you,” said another. All Ed could do was say, “Thank you,” occasionally adding, “It means a lot.”

Kim drove the family back to Dallas, with Ed in the passenger seat. They held hands most of the way. Ed often turned to look back at Kyra watching TV on her laptop and Zach playing with his smartphone. Now fifty, he had seen modern technology like that only on the prison TV, in shows and commercials where kids sat in backseats glued to their devices while the parents sat up front—and now he was living it. They stopped for gas at a Buc-ee’s, and Ed was dumbfounded at the rows of automatic toilets and faucets in the men’s room.

When Ed walked into the Cedar Hill home that Kim had bought in 2006, he couldn’t believe the high ceilings, the luxurious brown couch, the big-screen TV. Kim had assured him that it was his home too, but he was having a hard time accepting it. There were photos of her and the kids everywhere; he was present in only a couple of prints, from their wedding.

The first thing he wanted to do was take a shower and put on his own clothes—Kim had recently gone shopping for him—then eat a seafood platter. Since parole restrictions barred him from going to a restaurant, Kyra fried a plate of catfish filets. Other family members and friends began arriving—a cousin from Tyler with her kids, a cousin from Dallas, Kelvin and his son, and Ruff. Ed ate nine filets.

The next morning, he woke up at 5:30 and opened Zach’s door. “Zach,” he said, “what are you doing?” Zach, who had been sound asleep, sat up groggily. “Nothing. What are you doing?” His father replied, “I just came to check on you.” Ed checked on Kyra too, waking her up. Soon everyone was in the kitchen making breakfast. Later that day he walked from room to room, as if making sure everything was real.

Kim drove him to check in with his parole officer. He had to report every Tuesday morning and submit to a weekly urinalysis (he’s not allowed to drink). He wore a GPS monitor, which went off if he ventured beyond the property lines at an unscheduled time. He had to clear every move in advance, whether it was going to church or going shopping with Kim.

Ruff stuck around for a few days. “I ain’t never had a lot of friends,” said Ed. But the two had an easy rapport and sat on the couch talking like old Army buddies, watching TV, discussing football. They stayed up late one night preparing a slab of ribs; the next day they smoked them and had a cookout. Ed found himself touching Kim and the kids all the time. He also kept asking Kim for permission—to get some water, to turn on the TV. “This is your home,” she’d reply. “You don’t have to ask.”

When they all went to church for the first time, Kim dressed them in varying shades of purple. Worshipping together was a dream of hers, something she had wanted to do for years. “We are a family,” she said. “We are one.”

In Ed’s first weeks home, he established a new routine: rise at 5:30, brew coffee in his new Keurig machine, and putter around the house and backyard. On Saturday mornings he washed the family’s cars, going over every inch. He watched football and walked Charlie, the family’s Yorkshire terrier. If a picture needed hanging, Ed fetched the hammer. “He’d been dying to be a husband and a father for twenty years,” said Ruff, who talked with Ed weekly. “He finally had the chance.” Ed and Kim hosted several get-togethers for family and friends, where Ed did the cooking, as his grandmother did in the old days.

“I’m never going to get those years back. I’m going to live for today, make every day count.”

Kim had told him he could relax and take his time finding a job, but Ed didn’t want to sit around. Three weeks after his release, he was loading trucks at a UPS warehouse, and in November he was hired by the City of Dallas water department. By early 2019 he was part of a three-man crew inspecting sewer lines all over the city. He loved the work: driving the truck, maneuvering a robot, watching the monitor, reporting the results.

In the months since, he has grown a light beard, which came in salt-and-pepper, and started wearing two square diamond earrings that Kim bought him. The family created a new photo wall in the house, adding pictures of all four of them—at church, at Christmas.

Sometimes, though, Ed still finds himself eaten up by anger—that he didn’t get to see his grandmother and mother before they died, that he didn’t get to see his kids grow up. There were times in prison when he had trouble remembering the faces of his kids. It was terrifying and infuriating then—and is still. He knows that some freed prisoners have a hard time letting go of their bitterness. “I don’t want to live like that,” he says. “I’ve been mad enough.” He’s learning firsthand that freedom isn’t going to solve all of his problems.

Ed had worried about bonding with his kids, mostly Zach. While Kyra sings in the church choir and is planning on going to medical school, Zach is very much his father’s son. He rarely smiles, and one of Ed’s hardest tasks since getting out has been establishing a rapport with him. It started off well: in September Zach took Ed to his driver’s test and, after he passed, asked whether he wanted to drive home. “I don’t know,” said Ed. “You can do it,” replied his son, and threw him the keys. When Ed mowed the grass, Zach, who never did yard work, brought out the Weed eater and joined him.

But Zach, like many other twenty-year-old men, is still trying to figure out his relationship with his father, and the two sometimes butt heads. Ed is anxious that his son, who is so much like him, might make some of the same mistakes he did—or even get in some terrible trouble that isn’t his fault. In March Zach moved out and got a place with a cousin. Ed worried, but Kelvin reassured his brother. “He was raised right,” said Kelvin. “All you can do is let him go.” To Ed’s relief, six weeks later Zach moved back in.

Recently Ed pulled out some of his prison lists and read them over. He’s been able to check off most of his goals. Some, such as getting a driver’s license, were easy. Others, like smiling, he’s had to work at. The thing Ed wants the most, though, isn’t on any of his lists. “I want my name back,” he had said in 2018, while still behind bars. “I want this mark off me, this stripe off me. I want to be able to talk to people without them saying, ‘That’s the guy in prison for killing that lady.’ ”

Exonerations take a long time, even when backed by an army of Innocence Project lawyers and well-intentioned podcast listeners. Clayton began the process in 2016 and eventually convinced the Smith County DA’s office to join her in filing a motion in 2017 for DNA testing of twenty crime scene items, including scrapings from underneath Griffin’s fingernails, rape kit swabs, and the substance from Ed’s shoe. Unfortunately for Ed, most of the biological samples were so old and degraded that they revealed only one full profile: Griffin’s. The exception was the semen stain, which unquestionably came from Moseley.

And the shoe debris—the substance that 26 years ago led investigators to believe Ed had been inside the trailer the night of the murder? DNA testing revealed that it belonged to an unidentified male. Not only was the tiny trace never proven to have been human feces, it had nothing to do with Elnora Griffin.

Clayton is now trying to track down the crime scene fingerprints so they can be analyzed using modern software and then plugged into a current database. She is also planning to challenge Ed’s conviction under a 2013 state law that allows a court to grant relief in cases based on faulty forensic science. Clayton would like to debunk the state’s feces theory once and for all—and exonerate Ed while doing so.

She’s had offers of assistance from an unlikely source: David Dobbs. In 2016 Dobbs received an email from Ruff laying out his reasons for believing Ed is innocent and asking for an interview. Dobbs responded, “Is this the Bob Ruff who called me a psychopath?”

Dobbs, who left the DA’s office in 2000 and now has his own personal injury practice, told Ruff to give him some time to look into the case. If Ed was innocent, he said, he wanted to help, possibly by assisting the current DA in tracking down and questioning Moseley, Walker, and Johnson.

“I’m open to the possibility that he may be innocent,” Dobbs said in June. “Anytime you have a circumstantial case without any conclusive forensic evidence, there’s that possibility. But this is not a clear case of ‘He’s innocent.’ We have work to do to investigate that. I feel a responsibility to do what I can.”

Ed is skeptical of Dobbs’s intentions. He knows there are many reasons that people get sent to prison for something they didn’t do. In his case, as in most wrongful convictions, it began with a deeply flawed investigation, with deputies focusing on one suspect to the exclusion of others. (Neither Hukill nor Waller responded to multiple interview requests.) But Ed thinks that the main reason he spent twenty years in prison is the prosecutor who sent him there. “Once Dobbs saw that none of the evidence pointed to me, he should have left it alone. Then he came over to the jail and talked to Kenny Snow, who was a known snitch. And they believed what he said!”

Ed’s not the only one who thinks Dobbs was trying to win his case at all costs. During Ed’s second trial, Victor Sirls, an old friend of Ed’s who had also been in the jail cell with Snow, was subpoenaed by Ed’s team to testify. The day before his scheduled testimony, Sirls said that Dobbs summoned him to a vacant jury room. “He said if I testified for Ates, they’d get me,” Sirls recalled. “Dobbs said if I fucked this case up, he’d fuck my case up—those were his exact words.” (Dobbs denied this.)

Many others have complained about Tyler prosecutors over the years. In 2000 the Houston Chronicle ran a front-page story on the Smith County justice system, in which defense attorneys claimed that the DA’s office would do anything to win a case. “It’s simply a pattern of lying, cheating and violations of the law by Smith County prosecutors that wouldn’t be tolerated in Harris or Dallas County or any of the other, larger offices in the state,” said Houston attorney Paul Nugent, who represented Kerry Max Cook. A principal tactic, critics charged, was making secret or implicit deals with jailhouse informants like Snow, which are required by law to be revealed to the defense. Dobbs, quoted in the story, denied all allegations.

Dobbs recently contended that you can’t look at Ed’s case—or any other from that era—in isolation. In a conservative, pro-law-enforcement community, he said, he was doing the job voters expected of him. “It was the nineties, the war on crime. We were doing cases on the fly.” That decade saw Texas send more people to prison than any other state—and Smith County contributed its fair share. In the months before Ed’s second trial, Dobbs was juggling three other murder cases. In his twelve years, he would try at least fifteen death penalty cases and win all but one. “As a DA,” he said, “you’re like Mel Gibson in Braveheart, swinging your sword all the time. You can’t stop and look closely at a tree. You’re always under siege.”

It wasn’t a war to Ed, at least not at first. To Ed, it was a bunch of men with badges who seemed determined to prove he was a brutal killer. “They didn’t care about anything,” he said recently, “as long as there was a conviction.”

He spoke on a Sunday in late May, as he and his family were preparing to go to a Memorial Day crawfish boil at a cousin’s house.

“They had their minds made up as soon as they heard I had been in prison in Oklahoma. All they had to do was look at it a little closer, do a little more investigation, and it would’ve made a big difference.”

He paused. “I’m never going to get those years back. I’m going to live for today, make every day count.” At the party, he would see family members he hadn’t seen in decades, and he was eager to get going. “I’ll never get those years back,” he said again, “and I’m not going to even try.”

This article originally appeared in the August 2019 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Crowdsourcing Justice.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Longreads