In the fall of 1969, I left my hometown in the Houston suburbs for Wharton County Junior College, about an hour’s drive southwest of the city. I was excited for classes in English literature and psychology, but my main focus was on making friends. On Friday nights, my roommate and I did cartwheels and cheered on the football team under the stadium lights. We often gathered under a large oak tree outside our dorm to listen to music, smoke joints, drink Boone’s Farm wine, and talk through the night. We debated whether the Rolling Stones or the Beatles were better; we heard a rumor that Paul McCartney was dead and listened to “Revolution 9” backward to find clues. Through a haze of smoke, we heard “Dead is Paul” and tearfully toasted him. It was an innocent time.

One day in early October, I looked in the mirror over my bureau and noticed I was getting a bit chubby. I chalked it up at first to my kolache habit, thanks to the local Czech bakery. A few days later, however, I grew worried and decided to make an appointment with the campus doctor for Friday afternoon, before driving home for the weekend. After the doctor performed an examination he looked me over with narrowed eyes from behind his thick black glasses. “You’re six months pregnant, young lady,” he told me. “Go home and tell your parents!” He brusquely showed me the door and I stumbled out, stunned with humiliation and shame.

It took an hour to drive home. I sobbed through tissue after tissue and even pulled over to cry. When I walked through the front door at home, I was enveloped by the comforting smell of the chicken soup that my mom was making. I told her I was pregnant, and Mom put down her spoon, walked over, and held me in her arms. I felt safe.

The atmosphere changed when my father came home. When my mother told him the news, he was furious and blamed me for intentionally getting pregnant “to hurt your mom.” I didn’t understand his logic. He continued to curse under his breath as he went to the garage to the beer refrigerator. I can still hear the sound of the can opening—never a good sound.

When he returned, my father threatened to kill the boy who “did this to you.” He knew who the boy was: my high school boyfriend, whom I had broken up with that summer before I left for college. As the star quarterback—tall, funny, blond, good-looking—he was cocky as hell and spoiled. We had both partied, downed beers, and looked for any private places—in barns, in the back seat of his powder-blue Corvair convertible, at the beach. It’s an old story. We weren’t careful; I wasn’t on birth control, and he wasn’t using condoms. In those days, there was no sex education. I thought pregnancy couldn’t happen to me.

My parents quickly decided it would be best not to tell my ex-boyfriend or his parents about my pregnancy. Marriage was never up for consideration: if we had wedded, everyone in town would have known why. As for other options, I knew I didn’t want to be dependent on my parents to help raise my child. And I’d never even heard the term “single mother.”

We built a scaffolding of lies to ensure that no one else knew I was pregnant. Men—my mother’s ob-gyn, our minister, my father, and my father’s boss—made all the decisions, and my mother and I just went along with them. I was to tell my professors and friends I had to drop out of college and go to work. (When I did, none of them asked me why I was leaving. I suspected they knew.) Then I was to go to a home for unwed mothers, give up my child for adoption, and resume my life, never telling anyone. I was told the time would go quickly.

Fifty years later, I’m now seventy and haven’t lived in Texas in decades. But reading about the state’s new abortion law, which effectively bans the procedure before many women even know they are pregnant, I’ve been thinking about my experience. The era before Roe v. Wade that Texas lawmakers seem to want to return to—a patriarchal time when women had no agency over decisions about their own bodies—is one we must not usher back in.

My family was a typical sixties Father Knows Best family. A working dad, a stay-at-home mom, three daughters, a dog, a station wagon, a welcoming home with a swimming pool. When my father and I were getting along, we bonded over food and tried Houston’s Jewish, Greek, and Lebanese delicatessens. My mom channeled her artistic energy into cooking à la Julia Child as well as oil painting and raising her daughters. We went on car trips, had pool and slumber parties, and ate sunrise breakfasts on the beach. All looked well on the outside. But my pregnancy peeled back the veneer of what seemed to be a perfectly functioning family and revealed truths we were unprepared to deal with.

When I told my family I was pregnant, no one asked me what I wanted. If they had, what would I have said? I had no voice. My father made arrangements, I packed a suitcase, and my parents drove me to the Methodist Mission Home for unwed mothers, in San Antonio. They made up stories to explain my absence to friends, family, and neighbors: I was either away on a trip, busy with my studies, or just gone. They didn’t confide my whereabouts even to my grandparents. It must have been agony for them to have to be dishonest.

On the drive to San Antonio I sat in the backseat, while Mom and Dad chain-smoked in silence up front. Peering out the window, I felt like I was watching my life roll by. After driving for four hours, we turned onto an unpaved road that curved through the Texas Hill Country. The Methodist Mission Home looked like a peaceful retreat, its landscape dotted with sage, scrub oak, and mesquite. But once we entered the main building, a dark cloister with heavy furniture, I felt suffocated. I could not think of a future for myself.

We were met by a petite social worker in a wheelchair who had short dark hair and brown eyes. We talked about rules and daily activities. She was kind but had strict boundaries. She never asked me how I felt, what I knew about giving birth, or if I was ready to give my child up for adoption.

After initial introductions, she asked me what name I’d like to be called while at MMH. She asked this as if it were a normal question, but it took me by surprise. I realized I had to be anonymous; the secrets would continue, even at this place where the truth of why I was there was obvious. Unprepared, the only name that came to mind was my younger sister’s, Janice, which has always felt to me an odd choice.

I was at MMH for almost three months, spending Thanksgiving, Christmas, and my birthday there. The days passed slowly. I was given a job in the front office filing and answering the phone. Other times, I helped in the kitchen, cooking and washing dishes. Responsibility and keeping busy made things feel normal.

Occasionally we were driven offsite. Every so often we’d head to a hospital in San Antonio for doctor’s appointments. The birth process was not mentioned there; details were deemed unnecessary since we were just vessels, not to be real mothers. Another time, a group of us were driven to the local mall to see a movie. I don’t recall which one, but I do remember how we appeared: a pod of visibly pregnant unwed teens, moving in unison through the mall to the theater, aware we were being stared at. I wanted to disappear.

In our free time, we were encouraged to work in the crafts room—sewing, knitting, making ceramics. The first month I was there I made a round turquoise-glazed dish with a lid. I still have it, after fifty years. Kitschy as it is, I can’t let it go. It became a talisman: I was there, I survived. I spent most of the rest of my time reading in my room or in the library practicing my typing skills. I became obsessed with Edna St. Vincent Millay’s poem “Renascence,” which she wrote in 1912, when she was nineteen. “All I could see from where I stood / Was three long mountains and a wood; / I turned and looked the other way, / And saw three islands in a bay.” I typed the 214-line poem, then read it silently and aloud. Millay’s lyrical language and imagery of birth, death, and rebirth felt symbolic of my state of mind.

As time wore on, I became more aware of movement, of kicking. I would take long, hot showers—where no one could hear me crying—holding my pregnant belly, rubbing gently. I watched the water flow down my swollen breasts, preparing to sustain a life. I was in awe of my body and felt a secret joy and peace from this child forming in my womb. I felt love.

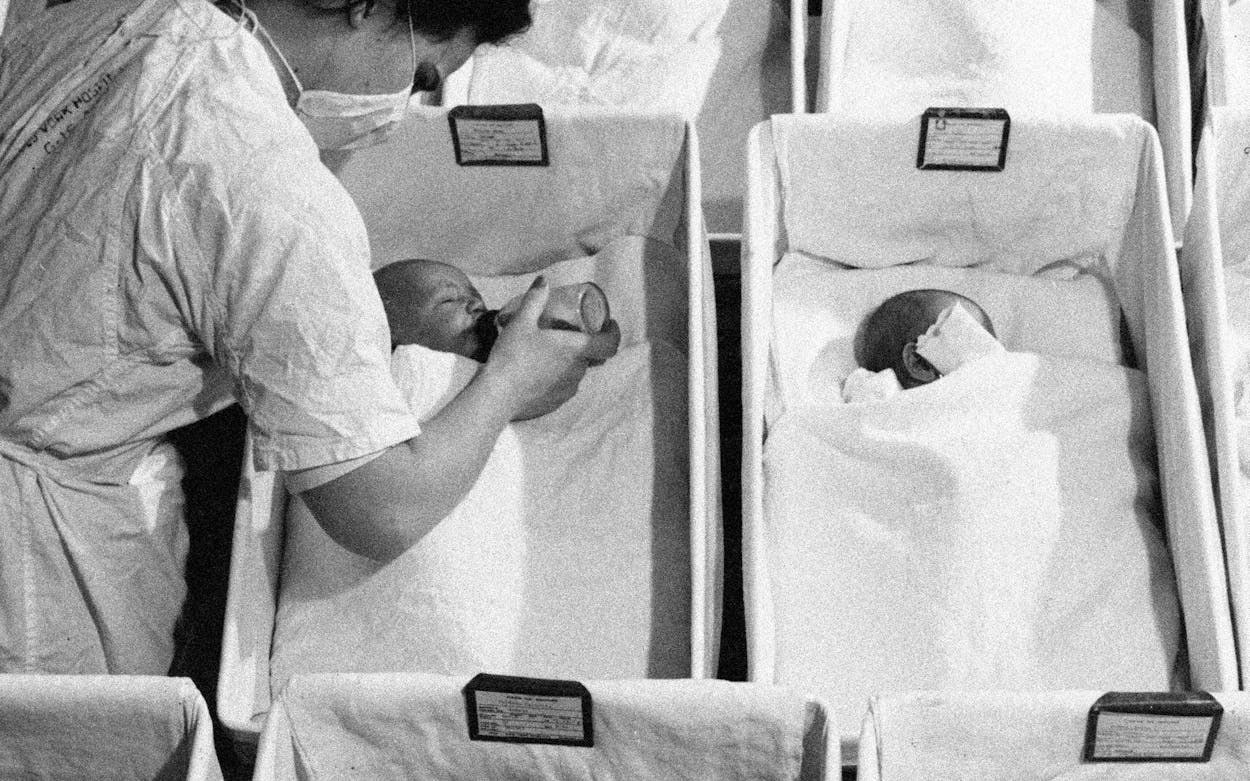

One morning in January, as my due date neared, I was told my labor would be induced on the doctor’s schedule. I packed a small suitcase and left for the hospital with a couple of other girls. Once there, I was prepped and given an enema, a shot of Pitocin to induce labor, and an anti-prolactin drug to dry up my breast milk. My water was forcefully broken. I was so heavily drugged—in “twilight sleep”—that while in labor my body felt completely out of control. I remember calling for my mother. As I slowly surfaced, I looked up and saw faces smiling down at me. Through the fog, I heard that I had given birth to a girl.

All I wanted was to see her. “Where is my baby?” I clamored. “Where is she?”

Nurses calmed me and told me my baby was healthy and in the nursery. I asked to hold her, starting to panic. A nurse told me it was for the best that I didn’t. I was blinded and felt helpless with a pain and grief I couldn’t define.

I was taken to a postpartum wing with the other girls. We were zombies, walking around in shock and crying from a sad brew of postpartum depression, loss, and trauma. A beautiful young girl from Mexico, who spoke only Spanish, cried in her bed. She must have felt so isolated and alone. I wanted to reach out to her but didn’t have the words.

Before they could give my baby to the couple who adopted her, I had to sign legal papers saying I was voluntarily relinquishing her and that it would be a “closed adoption” under which I could never contact the parents or the child. My hand shook so violently that I kept dropping the pen and could not sign the papers. After some time, my social worker brought in a tape recorder and had me read the legal script aloud.

On the day of the adoption, I kept asking if I could see my baby and was told, again and again, that it would be best for me—and her—if I didn’t. One nurse, however, whispered to me that I legally had the right to see and hold my baby. It was the first time during my whole pregnancy that I felt empowered to make my own decision. I could hear my baby crying in the next room, where her adoptive parents were holding her—and I insisted on seeing her. A nurse brought her to me. I’ve never regretted the decision. As soon as she was put in my arms, we both stopped crying. I quietly held and rocked her. I can still see her face. She was beautiful.

My parents picked me up at MMH a few days later, and we left San Antonio much as we had come. While we made small talk, I still felt disconnected. From the time I arrived home and for some years into the future, time held no meaning. Events happened, but I cannot tie most to the year they occurred.

After I returned home, I picked up my life, got a job, made new friends, and moved to Houston proper. I told my grandmother where I had been during my time away, and she said she had suspected the truth. She reached for my hand and looked at me with tears in her eyes and with so much love and understanding that no words were necessary. A few years later, I married a guy who made me laugh, and we moved to Austin. A few more years passed, and I got divorced and moved to Tucson with my dog and then, after a while, to Denver. I didn’t go back to college until I was 26. I never returned to Texas except for trips home to see family.

Growing up, I was fascinated with the parable of the mustard seed in the Gospel of Matthew, in which Jesus compares a small seed to the kingdom of heaven. I was captivated by how something so small could grow into something so large. Looking back on those years immediately after leaving MMH, I can see I was sowing my own mustard seed: a rage that would lie dormant for years.

After my pregnancy, I placed my trauma and grief in a box, securely wrapping them in brown paper with no bow. Only after years of avoiding the box and functioning with the help of drugs, alcohol, and an anger I couldn’t define did I find help. It finally felt safe to unwrap the box and slowly release the grief and pain that had been waiting patiently inside. The mustard seed had sprouted, and I had work to do. There are thousands of Texas women with stories like mine. We carry them quietly, but they’re always with us.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Abortion