For years, the tantalizing prospect of Texas becoming a “purple” battleground state has motivated Democrats—who have had their hopes dashed in election after election. However, the 2018 midterms showed cracks in the GOP’s hold on the state, with Democrats picking up congressional seats in districts that were drawn by Republican mapmakers to be easy holds. Now polling suggests that 2020 could see further gains by Democrats.

While all eyes are on the presidential campaign, and, er, some eyes are on the surprisingly low-profile Senate race between GOP incumbent John Cornyn and Democratic challenger MJ Hegar, the fiercest battles in Texas are over seats in the U.S. House of Representatives. Four years ago, the state had just one competitive congressional race; this year, there are a dozen races both parties are acting as if they’ve got a real shot at winning.

Today, we’re continuing our “Get to Know a Swing District” series with a look at Texas’s Third Congressional District.

The District

History

Many districts in Texas are gerrymandered. The Third Congressional District isn’t one of them. Even when Texas was a Democratic stronghold in the seventies and eighties, the district was a GOP seat. (It was held by Democrats for about a century before flipping in 1968.)

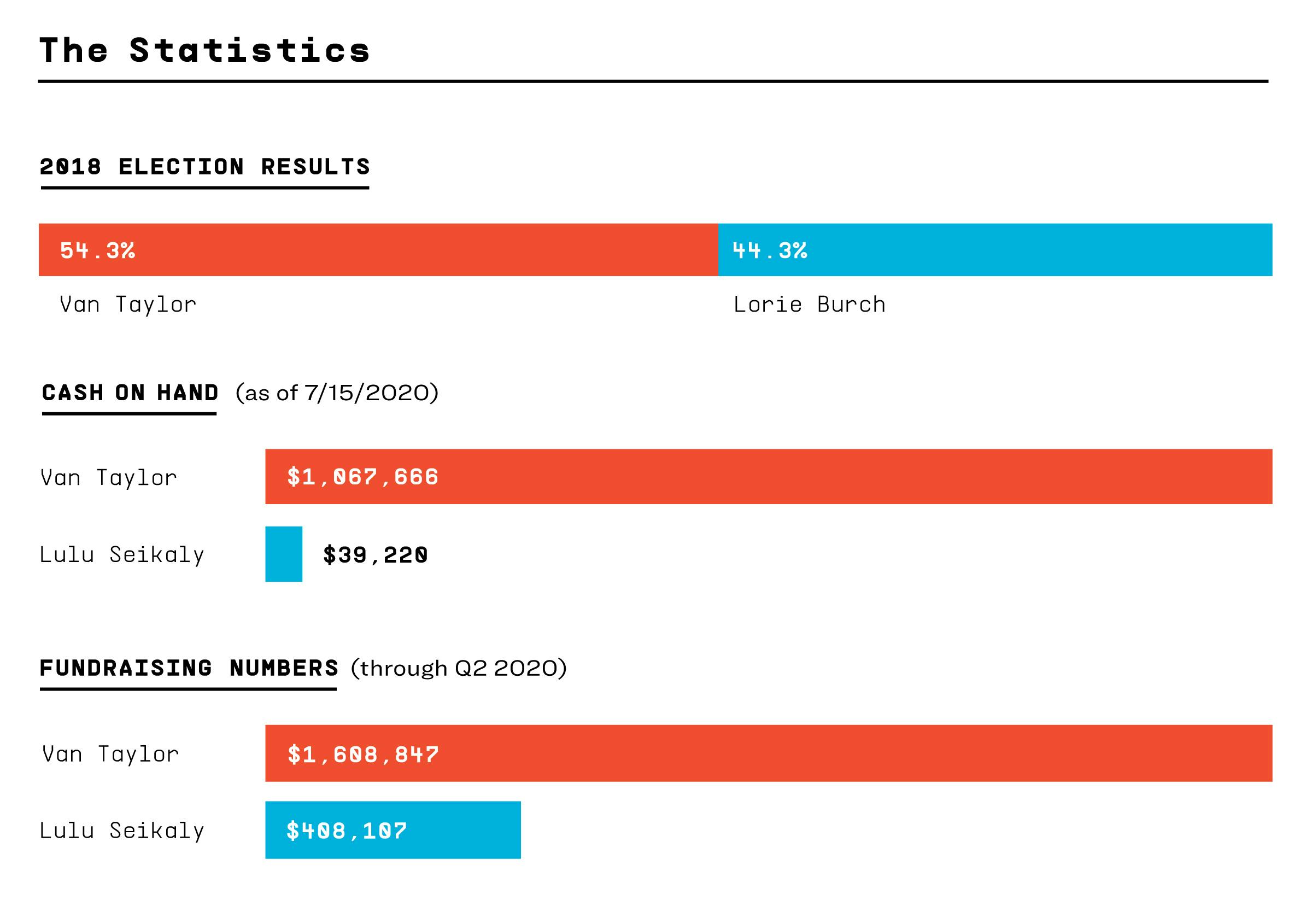

Republican Sam Johnson held the seat for fourteen terms, from 1991 until his retirement in 2019. During his time in Congress, Johnson never faced a competitive election. Indeed, in half of his campaigns he didn’t even face a Democratic challenger—and when he did, he sailed past him by 20 or more points. After Johnson’s retirement, Texas state senator Van Taylor won the seat. His campaign in 2018 wasn’t quite as dominant as his predecessor’s had been, however: the district went from one Johnson won by a 26-point margin in 2016 to one Taylor won by only 10 points.

What It’s Shaped Like

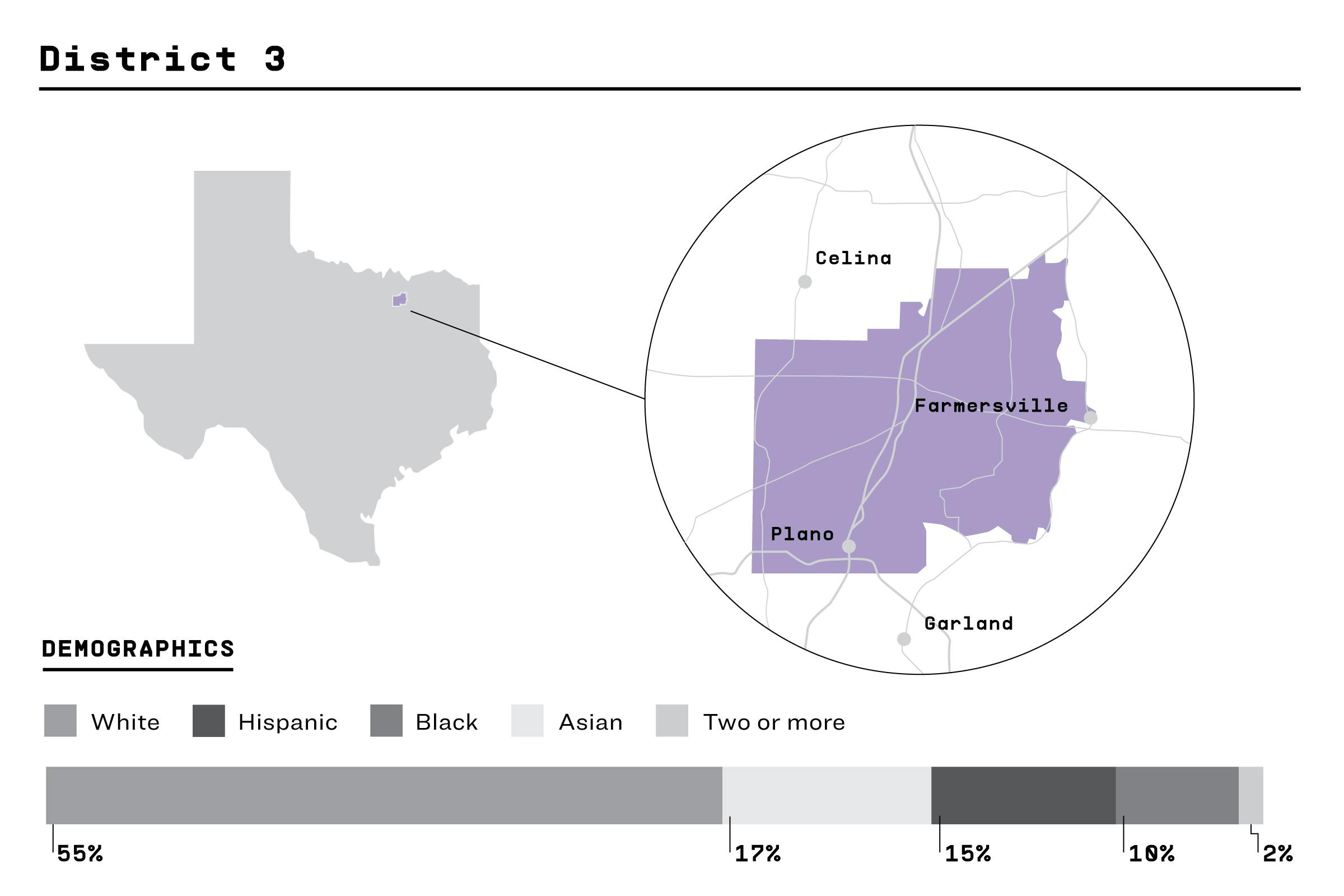

Believe it or not, TX-3 is shaped as you’d expect a congressional district to be in the absence of partisan engineering—it’s just a big ol’ chunk of Collin County, without wacky borders or cutouts, stretching three hundred miles to scoop in a swath of likely Democratic voters. If you squint, it looks like a dog’s head. It includes the northeast Dallas suburbs of Plano, Frisco, and McKinney. The Cowboys practice in Texas’s Third Congressional District (but they play their games in the Sixth).

The Candidates

Meet Van Taylor

An Iraq war veteran and real estate investor, Taylor entered the Texas House as part of the tea party movement in 2010, and spent two terms as a member of the lower chamber before seeking a promotion to the state senate. In 2015, he replaced current Texas attorney general Ken Paxton as the senator for Texas’s Eighth Senate District, which overlaps with the congressional seat he’s now seeking northeast of Dallas. He spent another two terms in the Lege before turning his eye to the U.S. House of Representatives.

Taylor’s campaign website touts his commitment to bipartisanship. While a 2019 Dallas Morning News profile highlighted his relationships with both Democratic and Republican representatives, his voting record places him in line with President Trump 95 percent of the time. (In the Texas House he gained a reputation for being difficult to work with, and earned a spot on Texas Monthly’s “worst legislators” list in 2013 after angering Republican and Democratic lawmakers alike with his contentious approach to legislating.)

Taylor’s 2020 campaign is built around the issues that Republicans have had success running on in Texas for decades. He’s for “market-based” health care, and his “economy and jobs” platform calls for a balanced budget amendment and cutting “red tape.” Taylor’s a well-funded candidate, and, through quarter two of 2020, he had raised more than $1.6 million, with more a million available as cash on hand.

Meet Lulu Seikaly

The daughter of Lebanese immigrants, Seikaly is a North Texas native and labor and employment lawyer. The 2020 campaign marks her first step into politics. She survived a close Democratic primary in March—when she took first place in a field of three by just 514 votes—before handily winning the two-candidate runoff election.

Seikaly’s campaign, similar to those of many suburban Democrats, stresses health care (she’s a “public option” Democrat rather than the Medicare for All variety), education (including support for universal pre-K), and “strong,” if unspecific, action on climate change (she told the Dallas Morning News that she doesn’t support the Green New Deal because she doesn’t like some of its economic provisions). She favors protecting abortion access, passing the DREAM Act to create a path to citizenship for undocumented residents of the U.S., and universal background checks for buyers of firearms as part of a gun control package. Her race only recently landed on the battleground radar—the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee added it to its list of targets in late August—which helps explain why her fund-raising numbers are a bit sluggish compared to some of her cohort of Texas Democrats seeking to flip districts. She’s raised $409,000, and has just under $40,000 in cash on hand.

The Upshot

Why It Could Flip

The story of Collin County is the story of Texas writ large, electorally: for years, it was so reliably conservative that Democrats saw no point in competing. But recently, there have been hints of a realignment. In 2018, Texas’s Thirty-second District, directly adjacent to TX-3 and similarly red since the Legislature redrew the congressional map in 2011, flipped blue—while the Third ended up closer than it had been in decades.

Seikaly is well positioned to take advantage of the shift. The district is increasingly diverse—white voters made up more than 59 percent of the district in 2015 but just 55 percent in 2019, a significant change over a short period of time. There haven’t been any recent nonpartisan polls in the race, but a July survey of registered voters from the DCCC and Seikaly’s campaign found the Democrat down by only six points, and a poll of likely voters from mid-September by the same groups showed her trailing by just one point.

Why It Probably Won’t

TX-3 may butt up against suburban parts of North Dallas and a sliver of Collin County that flipped blue in 2018, but Plano, Frisco, and McKinney are generally more conservative than the suburbs immediately to their south. Does that mean that Taylor will cruise to reelection the way that his predecessor did? Hardly, but he’s got a lot more money than his opponent, and an edge in polling. Seikaly’s internal poll may have the race within the margin of error, but it doesn’t show her winning, and Taylor’s internals show him with a thirteen-point lead. That’s close to the margin by which Trump won the district in 2016 (though a lot larger than the Ted Cruz’s three-point margin over Beto O’Rourke in TX-3 in 2018), so if those GOP voters come back to the party in 2020, Taylor would do well.

The Bottom Line

In the 2018 senate race, Texas’s Third Congressional District was more conservative than the state as a whole—but by less than half a point. This means the House race in TX-3 might be the best one to watch to see what happens statewide: As the New York Times’s election wiz Nate Cohn noted, if Democrats win TX-3, then they’ve probably also flipped the state for Biden, and potentially even for MJ Hegar. The Cook Political Report has the race as a “lean Republican,” meaning it’s more likely than not that Taylor wins.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Plano

- McKinney

- Frisco