Texas officials are mourning the untimely passing of Chad Foster, the 63-year-old former mayor of Eagle Pass who stumped against the border fence. Foster died of cancer at a Houston hospital Saturday.

Foster became a familiar face at “countless hearings” in Washington, D.C., Austin, and along the border where he aired his concerns about the Secure Fence Act in his role as head of the Texas Border Coalition, according to the Rio Grande Guardian. (The Texas Border Coalition is a group concerned with “economic and development issues of towns along the Texas-Mexico border,” according to the AP.)

Foster, a realtor by trade who used his fluent Spanish to work with ease on both sides of the border, was elected mayor of Eagle Pass in 2004 and served three terms. The current treasurer of the Texas Border Coalition, Eddie Aldrete, told the AP he considered Foster to be a “giant.” “He was one of those rare people that truly loved the bilingual, bicultural essence of what makes South Texas,” Aldrete said.

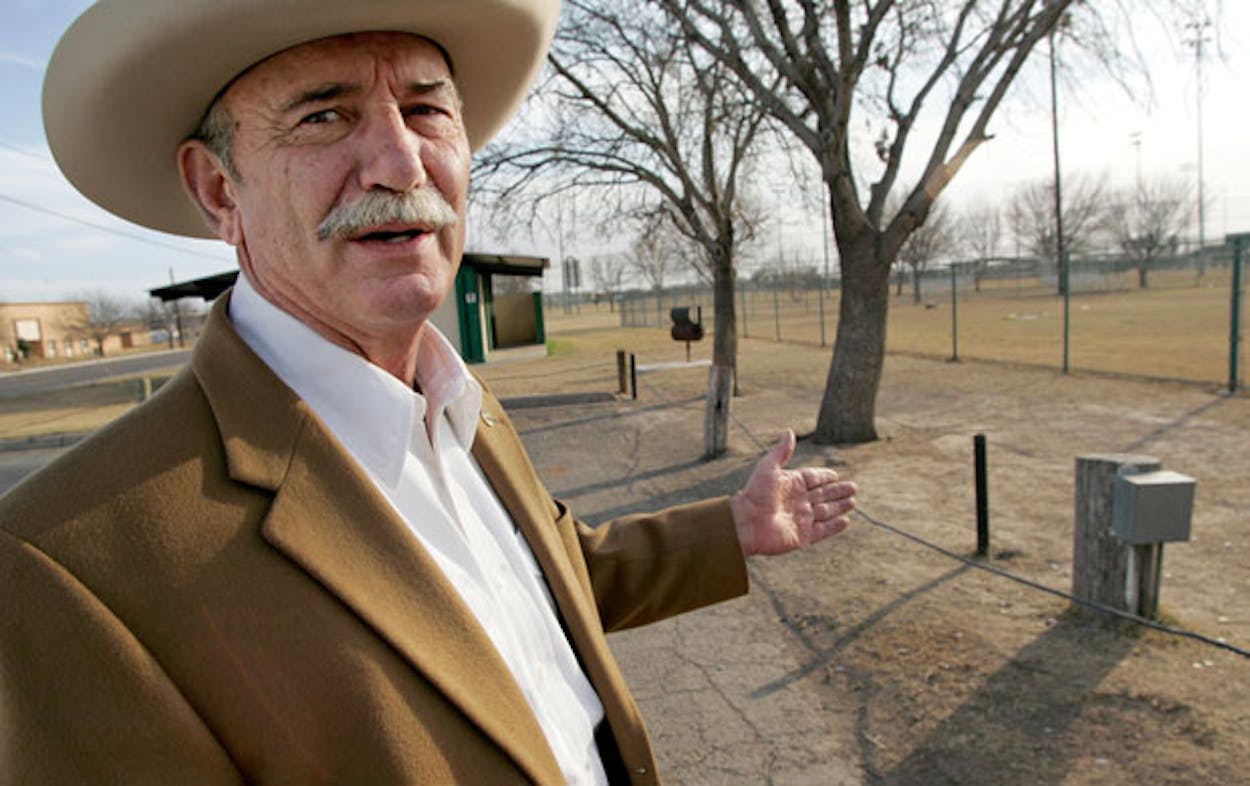

Foster, Aldrete reminisced, would always wear his tan cowboy hat (which he called his “Texas toupee”) even when appearing in front of Congressional committees. “That was part of his personality,” Aldrete said. “He wanted to convey a sense of uniqueness and pride in being a Texan.”

Former Laredo Mayor Betty Flores said Foster was always thoughtful about his stances. “He never shot from the hip. He knew what he was talking about and he stuck to it. He brought attention to the issues of the border. I mean, how many times has the United States turned its back on the border? Chad was a champion of the border,” she told the Guardian. “He always looked nice, he was always presentable. He was a gentleman first.”

For her November 2007 TEXAS MONTHLY story on the proposed border fence, Karen Olsson met with Foster in Eagle Pass and summarized his feelings on the border fence thusly:

From Laredo I had planned to go south to the Valley, but first I drove north to Eagle Pass, to meet with Chad Foster, that town’s mayor and the current head of the Texas Border Coalition. Foster told me that the way to reduce illegal activity is by improving visibility—rooting out the carrizo cane and salt cedar on the banks, installing more lights and surveillance cameras, and adding more agents. “We’ve learned to live with cameras. Why do we need physical barriers?”

Erecting a fence along the border would essentially split a community in half, he said, in reference to Eagle Pass and Piedras Negras, the town across the river. The DHS has maintained that a physical fence is most needed in urban areas, to slow an immigrant’s progress into a neighborhood or to a bus station, yet in urban areas the fence is especially despised, because of the ties between communities on either side of the border. (“Where Yee Haw Meets Olé” read a pamphlet Foster gave me touting the joint advantages of the two towns.)

Foster, who speaks Spanish, frequently attends events both informal and formal in Mexico, and he offered to take me over to Piedras Negras to show me the city. After driving for a while, we came to the Plaza de las Culturas, a swath of concrete where three small pyramids, along with a scattering of statues, commemorate the Mayan, Olmec, and Aztec civilizations. We walked inside one of the pyramids, where we encountered Fernando Purón Johnston, the director of the plaza. He offered to give us a sneak preview of an exhibit on prehistoric life in the region. Following him down a wide corridor, we viewed a human jaw, then a femur. Before long, discussion turned to the fence.

“People are very angry and very politicized here,” Johnston said. “Where’s it going to go? We have problems here, as at all borders, but a wall won’t contribute anything to get rid of these problems. The river doesn’t divide us, it unites us.” Foster nodded in emphasis. As we continued through the exhibit, the two kept speaking—each trading off languages—so that I learned little about prehistoric populations but plenty about the alliance between the two cities.

Outside we ran into a salty-looking man in boots and jeans and an old T-shirt. Apparently he had been a waiter at an event Foster had attended. “Chad Foster is more Mexican than the Mexicans!” he proclaimed. “Piedras Negras is very fortunate to have two great mayors.”

As we headed back to Eagle Pass, I asked Foster what he thought of the notion that he was in some sense Mexican. He replied without skipping a beat. “I’m a product of my environment,” he said, “and I love my environment.”

Foster was also among 82 visionary Texans who appeared in the May 2009 ideas issue of TEXAS MONTHLY. Foster advocated improving residential services in the colonias:

We must improve our colonias, the residential areas along the border that may lack necessities such as potable water and sewer systems, electricity, paved roads, and safe housing. Currently the state gives grant monies to counties to improve the colonias. But if improvements are not done to the specifications of nearby municipalities, it makes it more challenging for these municipalities to consider annexing a colonia, due to the additional expense of bringing it up to city standards. If these grant monies were given directly to city administrators, they could be invested by municipalities, with annexation as the goal.

U.S. Sen. John Cornyn, R-Texas, also marked Foster’s passing with a statement: “My thoughts and prayers are with the Foster family today,” Cornyn said, according to the Guardian. “Chad was a strong leader, a man of character, and a good friend to me. He will be sorely missed in South Texas.”

Memorial services for Foster will be held at 10:30 a.m. Wednesday at Our Lady of Refuge Church in Eagle Pass.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Obituaries

- Eagle Pass