It was dark when James Fulton climbed into his white Dodge Ram 1500 pickup on the evening of May 14, 2016. He and his friends Mark Warren and Dave Monicatti had played eighteen holes that afternoon at the Cascades Golf and Country Club and then met up with Warren’s wife for dinner and drinks at On the Border, a favorite Tex-Mex restaurant in Tyler. James had lived in the East Texas city for fourteen years before moving to San Antonio, in 2013, but he always looked forward to catching up with his buddies when he returned every month or so.

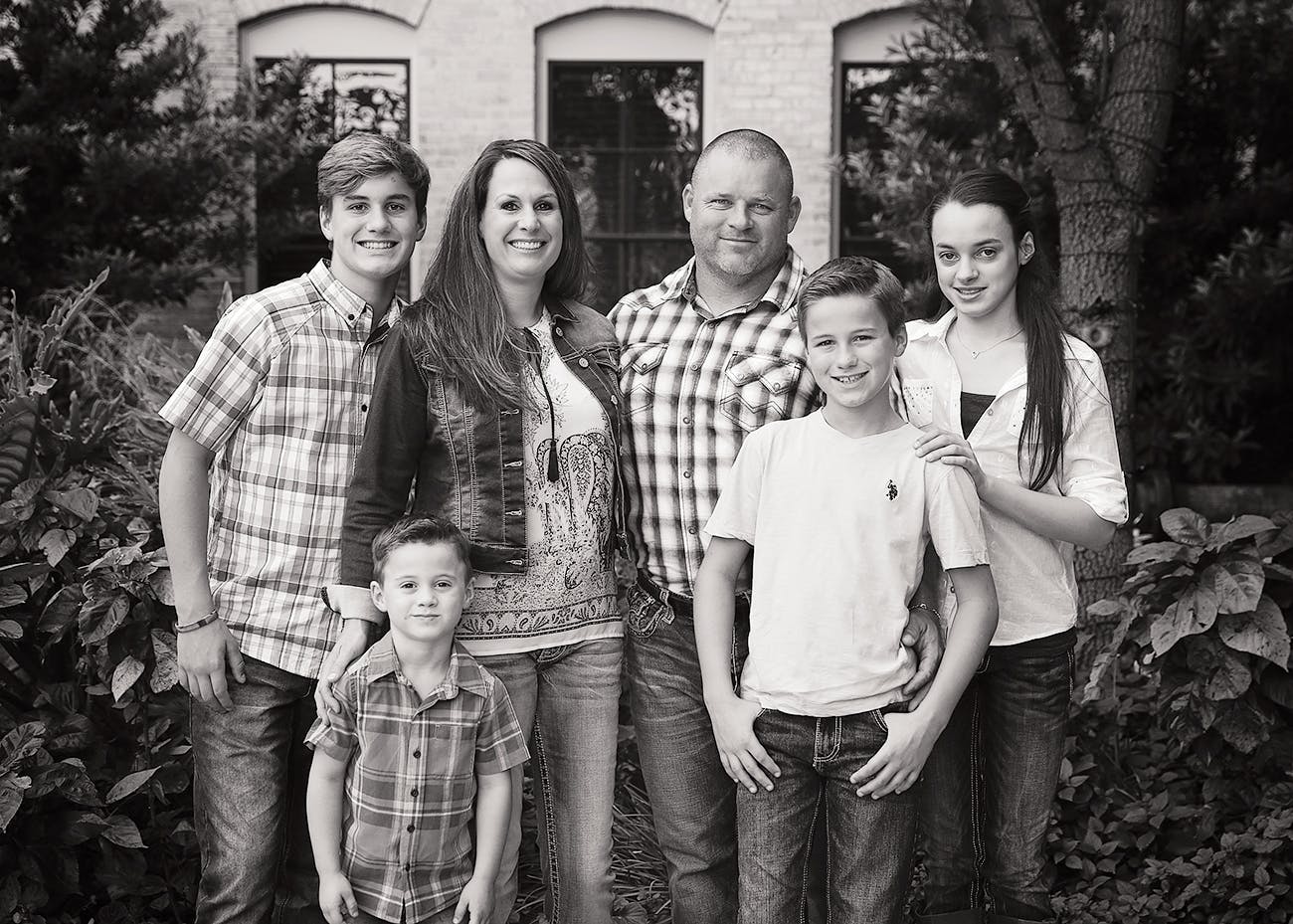

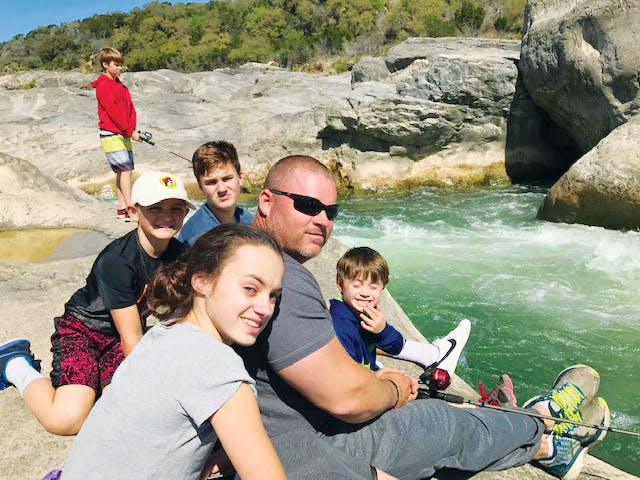

Though he was forty years old, James maintained a densely muscular frame. He had played fullback on his high school football team in Oklahoma, and at five foot nine and 230 pounds, he still looked the part. He was an outgoing guy; he and his wife, Audrey, a radiation therapist, and their four children had been longtime fixtures in the community. Tyler is a buckle of the Bible Belt, a city with a conservative culture, and the Fultons had loved living there. James taught for a decade at one of the city’s elementary schools and coached his kids’ football and baseball teams. Every Sunday, the family attended Green Acres Baptist Church.

In 2001, James, who is prone to restlessness, started a power-washing business on the side. He enjoyed the extra income, and it offered an excuse to spend more time outdoors. Then, in 2010, he seized on an opportunity in the booming oil and gas fields of East and South Texas. He left his teaching job to launch Fulton Oil and Gas Services, which specialized in cleaning pipelines. Soon, business was thriving, particularly in South Texas. At its peak, the company employed fifty people and maintained a fleet of fifteen trucks at a facility in Gonzales. James found himself spending more time on the road, away from his family. And so, in 2013, the Fultons headed south and settled in San Antonio to cut down on his drive time.

A year later, a sudden downturn in the oil economy gutted the business. James had to fire all of his employees, and by the spring of 2016, he had shut his company down and begun discussions with a bankruptcy lawyer. He was able to help keep his family afloat by starting other, less lucrative businesses—painting, welding, building decks—but it felt like things couldn’t get any worse.

In May he took the trip to Tyler for a business meeting, joined his friends for the golf game, and then headed over to On the Border. Just after 9:30 p.m. he eased out of the restaurant’s parking lot and onto busy Broadway Avenue to head home. He estimated he’d had seven or eight Miller Lites over the previous seven hours—he finished the bulk of them on the golf course and then had a couple of 19.5-ounce glasses of beer during dinner—but he later said that he didn’t feel impaired.

He made a right turn onto Grande Boulevard, a five-lane east-west thoroughfare that stretches across southern Tyler. From there he planned to hit Texas 155 toward San Antonio. James had made the six-hour trip many times—occasionally, he’d stop halfway to take a nap—so he knew the route well. He’d always been drawn to the natural beauty of East Texas, and he enjoyed the drive, even under cover of darkness. On his left, he passed the Hollytree Country Club, a course he’d played several times, and settled in for the long journey home.

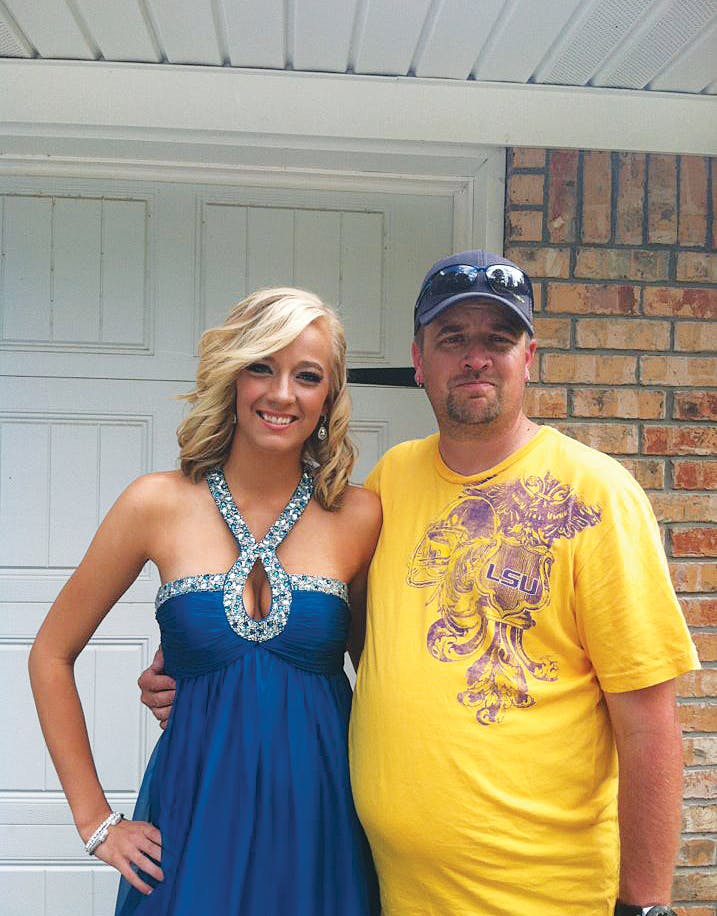

Less than a mile to the west, on the same boulevard, Haile Beasley idled at a stoplight in her black Ford Focus, on her way to a friend’s house for a late dinner. A lanky five foot ten, Haile was an ebullient twenty-year-old with long blond hair. Her mother, Jennifer Whittmore, said that many people joked that Haile looked like a baby giraffe. Self-deprecating, with a goofy streak, Haile made friends easily, and she was adored by her younger siblings. She would spend hours doing makeup with her sister, Ashley, and she attended almost all of her brother Sean’s baseball games, sometimes driving forty miles to sit in the stands and cheer for him. She had recently completed a dental hygienist degree from Tyler Junior College and was eager to begin her career. She also dreamed of settling down, getting married, and having kids.

According to a witness who was in the lane to her left, Haile was looking at her phone while waiting at the stoplight. When the light turned green, Haile continued east on Grande and approached an S-curve in the road, a stretch notorious for the many car wrecks that have occurred there over the years, as drivers misjudged their speed or simply missed the curve. The witness, a young woman named Kirsten Woodard, had continued driving on Grande, and she would later testify that she was checking a text message when her car was abruptly flooded with light. She looked up, honked her horn, braked hard, veered left into the center lane, and looked over at the black Focus just as a white pickup crossed two lanes of traffic and into a third, slamming into the Focus head-on. The two vehicles careered across the pavement, over a sidewalk, and into the grass, where the truck flipped onto its passenger side before coming to a halt.

The next thing James knew, a police officer named Donald Schick was peering through his window and asking if he was okay. “I don’t need any help,” James responded.

He was discombobulated, utterly confused as to what had happened. He had suffered a bruised nose and a few scratches on his hands, but he otherwise appeared fine. Another officer helped him crawl out of the truck, and that’s when James noticed the black car, its front end a twisted mass of steel. He watched police officers and firefighters scramble to extract the driver, and when Schick told him that the woman inside was dead, killed on impact, James started sobbing.

He couldn’t remember anything about the collision. “Something caught my eye, I looked left, and I’m rolling,” he said. (An hour later, he said that it was a deer he’d seen.) When questioned by Schick, James admitted to having had a couple of beers with dinner, so Schick escorted him to a nearby parking lot and conducted three field sobriety tests. James passed them all.

Around that time, Gregg Roberts, a detective with almost thirty years of experience, arrived and took over the investigation. He asked James if he would consent to a blood draw for a blood alcohol test. James had always heard that it was a bad idea to give a sample—there’s nothing to gain and everything to lose—so he refused. Roberts could have secured a search warrant for the blood draw if he felt there was probable cause that James was intoxicated, but he decided against it. James’s eyes weren’t glassy, nor was he slurring his speech. And so, a little after midnight, Schick wrote James a ticket for failure to maintain a single lane, and he let him go.

Detective Roberts wrapped up his investigation around 1:30 a.m. Then he steeled himself for the most dreaded part of the night. Accompanied by a chaplain, he drove less than a mile away to the modest brick home where Haile’s mom lived (she and Haile’s dad, Brian Beasley, had divorced in 2012). When Jennifer came to the door, she suspected that Roberts wanted to discuss a close friend of hers who was involved with an abusive partner.

“There was a terrible wreck tonight,” Roberts quietly explained. “Haile didn’t make it.”

Jennifer fell to her knees, her face pressed to the floor, screaming.

The morning after the crash, James posted on Facebook: “Last night I was involved in a fatal car accident. The young lady I hit did not survive. The family that lost their daughter their sister their niece needs your prayers. I don’t even know the feelings I’m feeling the sadness the agony for her and her family. I wish it had been me and not her.”

Later that day, James drove home to San Antonio. When he walked inside, Audrey and the children rushed over to hug him, and he started crying. In the days to come, James didn’t talk much about the wreck. He told Audrey he was haunted by the fact that the victim shared the name of their only daughter. Sometimes, he said, he would experience visions of Haile Beasley when he looked at Hailey Fulton.

Haile’s parents, meanwhile, seesawed between feelings of despair and frustration. The day after the wreck, Brian posted on Facebook: “I lost my baby girl yesterday she is no longer here. I do not know what I will do.” With tears in his eyes, he told a TV reporter, “You go through being angry, sad. No one sets out to kill someone. I understand, but my daughter’s dead and nothing can bring her back, and if justice needs to be done, it will be. If not, then that’s in somebody else’s hands.”

The local media flocked to the tragic story of the bright young woman whose life had been cut short. Their reports often featured the same photo of Haile, a selfie in which she grinned broadly, her eyebrows arched playfully over a pair of aviator shades, the very image of the promise of youth. The community response was impassioned. Neither of Haile’s parents had much disposable income, and Jennifer was worried there wouldn’t be enough flowers at the funeral. Yet when she walked into the Stewart Family Funeral Home for Haile’s visitation, “there were flowers everywhere,” she said. So many people showed up, many of them strangers, that the visitation stretched from two to four hours. Hundreds came to say goodbye to Haile.

The outpouring offered temporary comfort to her family, but Jennifer and Brian were confounded by the cops’ response to the wreck. There was no reason James would have crossed over two lanes of a road he knew well, they thought, unless he was doing something reckless. And James had admitted to drinking. Why hadn’t the cops ordered a blood draw? Why wasn’t James in jail?

Texas leads the nation in traffic fatalities. In 2017 alone, 3,721 people died on the state’s roads and highways, a number that has risen significantly during the past decade. A similar trend has played out across the country; nationally, road deaths have increased 34 percent since 2010. Many experts attribute this escalation to the fact that we live in an era of hyperdistraction. “People are paying more attention to smartphones and fancy dashboards than to the road,” said James Lynch, a vice president at the Insurance Information Institute.

Most car accidents are considered exactly that—accidents—and the drivers at fault are subject to civil liability for negligence, which means they didn’t use the care that an ordinary person would have used in the same situation. A driver can be charged with the much more severe act of criminal negligence when, according to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, “the seriousness of the negligence would be known by any reasonable person sharing the community’s sense of right and wrong.” When a death is involved, a driver can be charged with criminally negligent homicide. To make that charge stick, prosecutors must first convince a jury that the accused should have known that his behavior was putting someone’s life at risk. And they must also prove that the failure to perceive it was a “gross deviation” from what an ordinary person would have perceived.

In many negligence cases, there’s an awful lot of gray area. What an ordinary or reasonable person would do in any situation can vary drastically, and there’s no objective rubric for a juror to determine what counts as a “gross deviation.” When alcohol is involved in a fatal car wreck, these calculations become even muddier. In Texas, it’s illegal to drive with a blood alcohol concentration of .08 or above. But drivers can be held criminally responsible for a wreck even if they test below that level; by law, “intoxication” means “not having the normal use of mental or physical faculties” because of alcohol or any other substance, even noncontrolled substances, such as caffeine. It’s not illegal to drive with the mildest of buzzes, but if you get into an accident, that small amount of substance can get you into big trouble.

Ultimately, it’s not always easy to figure out if a crime has been committed. Such determinations can even change from one community to another. “The lines we rely on to identify criminals and figure out how the law applies to people’s actions are surprisingly indeterminate, particularly with homicides,” said Jennifer Laurin, a professor of law at the University of Texas at Austin. “We rely heavily on the idea that the police, prosecutors, and jurors can accurately figure out from external evidence what’s going on inside someone’s head. We depend on them to make subjective and nuanced judgments about, say, whether the defendant is taking a criminal or a noncriminal risk.”

In other words, as the families of James Fulton and Haile Beasley were discovering, justice is sometimes in the eye of the beholder.

Two months after the crash, Detective Roberts concluded his investigation by confirming his initial findings at the scene. “This case does not appear to meet the threshold for a criminal prosecution,” he wrote in a July 20 report. Roberts reviewed the original case file, which cited interviews with James’s golf and dinner partners as well as James’s server at the restaurant; all of them said James had shown no signs of intoxication. In addition, Roberts evaluated the data from the computers of the two cars and found that James’s speed wasn’t excessive (51 mph in a 45 zone, though the report did note that there was a yellow caution sign suggesting 35 mph) and that in the moments before impact, he hadn’t braked or swerved. James was inarguably at fault, Roberts made clear, and “driver inattention” was a contributing factor. But according to the evidence, his actions didn’t add up to a criminal offense. Roberts’s supervisor agreed with his findings, and the case was closed.

James was relieved. Haile’s family was confused and angry. Jennifer and Brian believed Roberts’s investigation was fundamentally flawed. They thought that James’s friends were not reliable witnesses, and they believed that James had driven straight into oncoming traffic because he was drunk or looking at a phone screen. Determined to see James held responsible for his actions, the two hired a local lawyer named Chad Parker and filed a wrongful-death civil suit.

In late August, James agreed to give a deposition. He told Parker that he was at fault and also that he had consumed seven or eight beers that day. In addition, he admitted that in the past he had driven away from On the Border intoxicated. At the end of the interview, Parker asked James, “You understand that you still run the risk of a criminal prosecution, maybe even more so, based on your testimony today?”

Yes, James answered. He wasn’t concerned, because he was certain the crash was an accident.

A month later, the two parties settled the civil suit for $1 million, the amount of liability insurance James carried through his businesses.

For Jennifer and Brian, the victory was hollow. It wasn’t James suffering the consequences—it was his insurance company. They had come to believe that James was the worst kind of driver, one who drank and drove and always got away with it, at least until he killed their daughter. They took James’s deposition to the office of Smith County district attorney Matt Bingham. By law, DAs have broad discretion over whom to charge with a criminal offense, and Bingham, who had worked in the district attorney’s office for 21 years, had a reputation as a man who was tough on crime and criminals—and very effective at putting them in prison. In 2015 his office managed a 94 percent conviction rate in the local district courts, 11 percentage points higher than the statewide average. Bingham also worked hard, as a supporter in a 2014 campaign ad said, to “aggressively represent the rights of victims.”

He had learned his job from his former boss Jack Skeen, who had been DA from 1983 to 2003, when he left to become a district judge and Bingham took over. Skeen was a legend as both DA and judge. “Skeen believes in law and order, and he sees himself as a protector of victims,” said a local attorney who didn’t wish to be named.

For a third of a century, Skeen and Bingham had led the Smith County justice system. On more than one occasion, though, their philosophy had led to unjust results. In one of the most notorious examples, Bingham and his assistants prosecuted the so-called Mineola Swingers Club cases, all in front of Judge Skeen, beginning in 2005. The cases involved allegations from a group of young children claiming they’d been forced to attend a “sex kindergarten” and perform erotic dances at a swingers club. There was no physical evidence, and the Mineola police found nothing credible in the outlandish stories, so they dropped the case. Then the foster mother of three of the children involved took the case to Bingham’s office, which indicted seven local adults. Four of them were eventually convicted and sentenced to life in prison.

By 2010, though, two of the verdicts had been overturned by a higher court, and a year later Bingham released all but one of the adults—including three who were still in jail awaiting trial—after they pleaded guilty to a lesser crime, arguably a tacit acknowledgment of their innocence. (Texas Monthly has covered these cases extensively.)

At the DA’s office, Jennifer and Brian met with Bingham and assistant prosecutor Kenneth Biggs. Please make this right, they implored. “If it is what you’re telling me it is,” Bingham said, “I’ll do everything I can to try and bring justice to your baby girl.”

Several weeks passed. Biggs checked in on occasion, telling Brian and Jennifer that the more he learned, the more he came to believe that James had indeed committed a crime. Then one day Bingham called and asked them to meet him at his office. Jennifer brought along her father, and Brian arrived with his wife. Bingham sat them down and explained that his office believed that the police were mistaken on that terrible night; they had had probable cause to take James’s blood. Then he informed them that he was going to present the case to a grand jury.

The four broke down in tears. Finally, they thought, Haile would get justice.

On November 28, 2017, James walked into Judge Skeen’s Tyler courtroom wearing jeans, boots, and a new long-sleeved plaid shirt Audrey had bought for the occasion. He was still baffled that prosecutors had charged him with criminally negligent homicide and accused him of using his truck as a deadly weapon. But he was optimistic about his chances. He and Audrey had left their four children under the care of a neighbor, assuming they would all be home together soon. In fact, James had turned down several offers from the DA’s office: in exchange for pleading guilty, he could have received five years probation. But he refused to plead guilty for something he felt wasn’t a crime, and he didn’t want to have a felony on his record.

Inside the courtroom, Audrey was wedged between her mother and sister, just behind James and his lawyer, James Huggler. On the opposite side of the small room huddled Haile’s family. There were clearly tensions between the two clans. Haile’s family felt that James had failed to show remorse commensurate with the tragedy, and Brian had aired many of his grievances on Facebook. The Fultons thought that such accusations were a gross mischaracterization and felt threatened.

From his opening statement, Huggler emphasized one salient point. “Is Haile’s death a tragedy?” he asked. “Yes, it is. Is it criminally negligent homicide? No.” The wreck was an accident, he explained, urging the jury to concentrate on the three seconds leading up to the collision, when James was distracted—focusing, as drivers often do, on things inside and outside their cars. “This case is going to be about those three seconds,” Huggler said.

The prosecutors, on the other hand, steered jurors’ attention away from that brief interval (the span, they claimed, was closer to five seconds) and homed in on what came before: James’s drinking. “Alcohol contributes to a person’s inability to handle distraction,” Bingham declared in his opening statement. The focus on alcohol only intensified throughout the three-day trial, as Bingham frequently found ways to bring up James’s drinking habits. He reckoned that James had downed 48 ounces at the restaurant, and he called as witnesses three law enforcement officers, none of whom had been at the scene, who claimed that alcohol would have affected his decision-making. “Any introduction of alcohol would impair somebody,” said trooper Barry Evans.

James didn’t have to be drunk to be found guilty of criminally negligent homicide, Bingham explained to the jury—although, since the police didn’t do a blood draw, “he might have been.” (Given James’s size and the amount of Miller Lite he drank with dinner, his blood alcohol concentration was almost certainly below the legal limit; a state’s witness estimated it to have been .04.) What mattered, Bingham argued, was that James had driven into oncoming traffic. “I don’t care if there’s a deer there,” he said. “Could be looking at a fairy-dust unicorn, for all I care. The fact of the matter is, he took his eyes off the road, and he crossed over pretty much the whole Grande extension and he hit a girl and killed her, didn’t he?”

Bingham played heavily to jurors’ emotions, constantly evoking Haile, the twenty-year-old victim who had “her whole life ahead of her.” At one point, he became emotional himself, explaining that he had become very close to the family. “I have an eighteen-year-old daughter named Haylee, and sometimes this case hits a little bit close to home.”

Jennifer was impressed by Bingham’s performance. She also felt that James was living up to her impression of him. He wore casual attire, which assistant prosecutor James Bullock mocked as “his drinking clothes,” and he did little to endear himself to the jury. In fact, his only display of emotion came on-screen: he was shown crying on a dashcam video captured the night of the accident. But later, in the same video, he referred to Haile as “the dead woman.” Many in the courtroom gasped audibly.

As the trial progressed, Audrey sensed that everything was going horribly wrong. She was unprepared for the state to place so much emphasis on James’s drinking, which felt like character assassination. It also seemed to her that Judge Skeen took the state’s side far more often than not, constantly sustaining his former assistant’s objections while overruling Huggler’s. It didn’t seem fair to her that Skeen hadn’t allowed Huggler to bring before the jury certain witnesses, such as the city’s custodian of records, who would have discussed the high rate of citations issued on Grande for driving into the opposing lane. Skeen also disallowed the testimony of a firefighter who would have described the many wrecks he’d been called to at that same S-curve. (Skeen declared the testimony of both witnesses irrelevant.) The judge had also refused to let Huggler question Detective Roberts about his recommendation that no criminal charges be filed. (Bingham noted that “there’s a constitutional discretion for the district attorney’s office to decide whether to or whether not to charge a criminal offense in Smith County, Texas.”)

By the time the trial wrapped, Audrey was panicked. She had never considered that James would actually go to prison, but as the jurors filed out of the room for deliberation, she feared the worst. When they returned an hour later, her fears were confirmed. Not only did the jury find James guilty of criminally negligent homicide, it ruled he had used his vehicle as a deadly weapon, which raised the possible maximum penalty from two to ten years.

She still held out hope that James, who had no prior criminal record, would receive probation. But the following day, during the punishment phase of the trial, the state called as its first witness Kirsten Woodard, the young woman who had been driving in the car next to Haile. After the crash, she told the jury, she was working as a bartender at the Cascades country club—the course James had played the afternoon of the crash—and on the stand she made a devastating allegation. James, she said, had returned to the Cascades about six or eight weeks after the crash to drink with friends. Woodard claimed he’d used his own credit card and that she had recognized his face from local media coverage.

For the next couple of hours, as a series of defense witnesses were called to speak about James’s compassion and selflessness—for example, Audrey’s sister Jamie declared, “His heart is pure”—Bingham repeatedly referred to Woodard’s damning accusation. “Where’s the regret?” he asked Jamie during her cross-examination. “Where’s the ‘I’m so sorry’ . . . if you’re back out at the Cascades after you killed her, doing the same thing you did when you killed her?” The tactic seemed to work. In his concluding statement, Bingham asked jurors to give James seven years. But when the twelve men and women retired and came back an hour or so later, they surprised even Bingham. James would be going away for the maximum: ten years.

“My heart is full of joy,” Brian posted on Facebook later that day. “We finally have JUSTICE FOR Haile Beasley.”

As Audrey lay awake that night at her parents’ house in Tyler, replaying key moments from the trial in her mind, the thing that stuck with her the most was Woodard’s testimony. It just didn’t add up.

James had told her that he had stayed away from Tyler after the accident, an assertion he repeated to Texas Monthly. And he wasn’t a member of the Cascades country club; his only access was through his friend Mark Warren. The statement about the credit card was confounding too; because of their bankruptcy proceedings, Audrey and James had agreed with their attorney to use cash only. And Audrey wondered how Woodard could have recognized James from the media, when, to the best of her knowledge, news reports didn’t actually show pictures of him until after the November indictment.

Audrey called Warren, who told her he had not gone back to the club with James. The next day he contacted the country club’s general manager, who told him there was no record of James ever using his credit card there, something the manager claimed she already knew because the DA’s office had subpoenaed those records a month before—and the club had emailed them a letter saying so.

When Warren reported his findings to Audrey, she was furious. The state had evidence that contradicted its star witness, yet prosecutors still allowed her to testify. They also failed to turn over the club’s letter to the defense, as they were obligated to do.

She was certain she could spring James with this new evidence. Huggler filed a motion for a new trial, alleging the state had withheld exculpatory evidence from the defense, which is known as a Brady violation. A month later, in February 2018, Judge Skeen held a hearing to look into the matter. By then Audrey had fired Huggler and hired John Hodges, a San Antonio attorney she and James had met at church. In court, assistant prosecutor Biggs admitted that he had not turned over the documents to Huggler, but he insisted it was an oversight. More importantly, he claimed he had told Huggler on two separate occasions that Woodard was going to make the allegation that James had returned to the Cascades. When Huggler, who was called as a witness, confirmed Biggs’s assertion, Skeen ruled in the state’s favor. There had been no Brady violation. There would be no new trial.

Despondent, Audrey drove home, uncertain what to do next. The following day she received an anonymous message on Facebook. “What happened this week on your husband’s case is a tragedy to the entire legal system,” the person wrote. “If I were you I would HIGHLY recommend filing a grievance with the State Bar of Texas on all 3 of the prosecutors.”

Successful grievances against prosecutors are rare, especially in East Texas. One local lawyer, who recently served for six years on a grievance committee that oversees Smith County, said that during his tenure he never received a single grievance against a local prosecutor. Statewide, between 2013 and 2018, only 24 complaints against prosecutors sent to the Texas Bar went to the litigation phase; just 13 of those cases led to sanctions. (By contrast, during the past two years alone, the State Bar has sanctioned 332 private attorneys.)

Hodges told Audrey it was probably a waste of time, but she was desperate, so she filed a grievance that accused Bingham, Biggs, and Bullock of withholding key evidence. She also filed grievances against Huggler and Skeen.

Then she began exploring other ways to free James. A friend at church suggested she write her state representatives, so she reached out to Donna Campbell and Kyle Biedermann, who replied that they couldn’t do anything since it was a local matter. She emailed Governor Greg Abbott, and a staffer replied that he couldn’t get involved until after the appeals. The Texas Rangers told her it was an issue for the appellate courts, and a staffer with the attorney general referred her to the local district attorney, the very person she had accused in her grievance. She wrote U.S. representative Lamar Smith, who didn’t reply; Senator John Cornyn, who did (it was a local matter, he said); and Senator Ted Cruz, who recommended she try Campbell and Biedermann. She called the sheriff, who didn’t call back, and the Innocence Project of Texas, which said it would look into the case after the appeals process.

In a matter of weeks, Audrey found herself attacking not just James’s conviction but the entire Smith County justice system. She created a website called JusticeForJames.org. “We have never been face to face with Evil as we have seen in Smith County Courthouse,” she wrote.

Soon, almost every surface of the Fultons’ living room was littered with documents relating to James’s case, from trial transcripts to a report from investigators hired by Hodges, which bolstered her low opinion of Woodard’s trustworthiness by expressing “extreme doubt” about her “veracity and credibility.” Woodard, Audrey learned, had gotten in trouble with the law numerous times, getting arrested for marijuana possession, “assault causes bodily injury family violence,” and driving with an invalid license. All of those charges were dismissed, but five weeks after James was convicted, Woodard was arrested for possession of methamphetamines and later pleaded guilty to a lesser charge. While Audrey knew that Woodard’s legal troubles didn’t mean she was a liar, they raised even more questions about her reliability as a witness.

Audrey developed a new nightly routine: after putting the kids to bed, she would hunker down at her computer, researching and composing posts for the website. Her youngest child would sometimes call out to her from his room. “Mom,” five-year-old Owen would yell, “could you just come to bed?”

The stress took a toll on everyone. Hailey, sixteen, suffered from insomnia. Her two eldest sons, Reid and Ayden, fourteen and eleven, each went into counseling. Ayden was eventually hospitalized with severe acid reflux that doctors attributed to high stress.

In her research, Audrey discovered newspaper and magazine stories detailing the long history of overzealous Smith County DAs and judges. She read about the Mineola Swingers Club cases, in which a high court determined that Skeen had “adopted ad hoc evidentiary rules that operated to assist the State in proving its case, while impeding appellant’s ability to defend himself.” She found a 2000 Houston Chronicle story in which an attorney accused Smith County prosecutors of “a pattern of lying, cheating, and violations of the law.” The story noted something Audrey already knew about: how harsh Tyler juries could be. One man, convicted of stealing a candy bar, got sixteen years.

Audrey’s grievances against Huggler and Skeen were rejected, but in March the State Bar decided that the allegations against the prosecutors had passed the initial threshold. A formal complaint would determine if there was “just cause” of “Professional Misconduct.” The Smith County prosecutors responded by claiming that the issue had already been settled at the hearing. Audrey countered by amplifying her accusations of misconduct, concluding, “The state has lied, concealed, cheated, and done anything necessary to seek a conviction in this case rather than to do their job and SEEK JUSTICE.”

Six months later, the State Bar surprised longtime observers of the Texas criminal justice system when it formally decided to go ahead with the grievance. Bingham, Biggs, and Bullock would be taken to the litigation phase and tried for professional misconduct. “The State Bar taking this to litigation even after the trial judge said there was no misconduct—that is very unusual,” said a veteran appellate lawyer who asked not to be named. “I think it’s a big deal.” A hearing was set for March 7 of this year.

To this day, members of Haile’s family refuse to use the word “accident” to describe what happened that night. They call it a “wreck”; Brian calls it “murder.” Almost three years later, they struggle to even talk about it. “I still can’t get any peace,” Brian said. “I celebrate her birthday in a chair at the cemetery. She didn’t choose that. I didn’t choose that.” James was the one who made the choice, he thinks. Brian and Jennifer believe you have to pay for your mistakes. It doesn’t matter that everyone drinks beer with their Tex-Mex and drives home. Not everyone kills someone.

“I don’t think James Fulton is a horrible person,” said Jennifer. “I think he made a horrible mistake and it cost my daughter her life. The Fulton children having to see grief counselors, being hospitalized—they don’t deserve that. But their dad did something he has to be held accountable for. Their grief doesn’t compare to the agony my children live through every day.”

Brian and Jennifer bristled at the grievance, which they considered a desperate attempt to secure a new punishment hearing. And they’re angry about Audrey’s allegations against the district attorney’s office. “It hurts to hear Matt Bingham attacked,” said Jennifer. “The man I consider my hero is having to suffer because he did the right thing for me and my daughter. I thank him for restoring some faith in the justice system.” (Bingham retired as DA in January.)

But any sort of lasting solace is elusive.

“People don’t understand what can happen when you get behind the wheel,” said Jennifer. “It’s not okay to be distracted. I don’t care if it’s alcohol or getting something out of the glove box. It’s so senseless, so pointless.”

Last fall, Audrey decided to put away the stacks of documents that had overtaken her living room. She felt it was time to put the case in God’s hands as well as those of James’s appellate attorneys, who filed an appeal in which they attacked the legal basis for trying James in the first place. They drew parallels with a 2017 case involving a fatal traffic accident in which the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals found the driver’s actions were careless but not “criminally culpable risk-creating conduct.” According to Hodges, criminally negligent homicide wasn’t designed for cases like James’s. “Turning your head for a few seconds is not enough. If it were, billboards would cause criminal negligence daily, and mothers would be potential criminals when they turn to police their children in the backseat. Turning your head creates an elevated degree of risk, but it’s an ordinary degree of risk.”

Audrey also knew she needed to spend more time with her kids. Now the tables of her house are once again crammed with puzzle pieces, toys, and schoolwork. But there’s one thing she’s refused to stash away: the family Christmas tree, which has been up since James went to prison in December 2017. She and the kids decided to keep it standing until he goes free.

Audrey and the kids visit James every month. For the first year, he was imprisoned at the Gurney Unit, just west of Palestine, where he helped the chaplain organize a series of Bible classes for hundreds of inmates. Audrey said that preaching in prison had given him a sense of purpose. But in December, they got a nasty surprise when he was transferred to the Price Daniel Unit, an hour from Abilene, where he hasn’t been able to preach at all.

Audrey got another unpleasant surprise in early February, when she was notified that the State Bar had dismissed her grievance. Such a dismissal isn’t unheard of; according to Audrey, the Commission for Lawyer Discipline (which oversees the investigators) agreed with the state’s point that the core issue had already been ruled upon by Judge Skeen. She was crushed.

The prosecutors, of course, were relieved. Biggs, who is now in private practice and had failed to hand over the country club’s letter to the defense, probably had the most to lose. “I felt I was under attack for doing what I thought was the right thing,” he said. He believes Woodard was telling the truth about James returning to the Cascades.

The whole experience made Audrey even more determined to free James, who won’t be eligible for parole for another four years. Recently, she stood up in front of four hundred congregants at the family’s church and reflected on her struggle to free James. She nervously read from prepared notes, pausing occasionally to dab tears. “I really need Him to move mountains,” she said. “It’s in my prayers and my children’s prayers daily.”

Three crosses sit in the grass on the south side of the S-curve on Grande Boulevard in Tyler. One is adorned with photos of twenty-year-old Rian Finkie, who died after losing control of his motorcycle and colliding with oncoming traffic on December 22, 2017, less than a month after James was convicted. Another simply reads “RDK,” planted for Rodney Kolac, a seventy-year-old who died just two weeks after that; he lost control of his Corvette and slammed into a truck. The third is decorated with eight photos of Haile Beasley. In each of them, she smiles irrepressibly.

Last spring, the city installed a series of bright yellow plastic poles in the center lane of the S-curve, a temporary measure until a concrete barrier can be installed. Many citizens felt the measure was a long time coming. The S-curve has for years been a place where the human capacity for error was greatly amplified.

Jennifer still visits the curve routinely to maintain Haile’s cross, swapping out pictures and adorning it with fresh flowers and, come Christmastime, decorating it with a small tree.

Brian doesn’t want to encounter the site of his daughter’s death, so he avoids the curve altogether.

Audrey drives this part of Grande often, since her parents still live in Tyler. The kids sometimes ask her to point it out when the family drives into town. As they lean into the curve, they all say a series of prayers: for Haile’s family, for the other families who have lost loved ones there, and for James to come home soon.

This article originally appeared in the March 2019 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Was It an Accident? Or a Crime?” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Longreads

- Crime

- East Texas