This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Rex Pigmon had seen oil spills on his West Texas ranch before. But the one on January 24, 1989, was different. The 62-year-old Winkler County cattleman sat in his pickup for a long minute, watching the stream of smelly crude flow across his land toward the road. He thought about getting out for a closer look, but the danger of poisonous gases and explosion made him stay put. He watched the spill for a few more seconds, then in a torrent of dust and flying sand, he wheeled his truck around and sped toward the pipeline pump station, about a mile away.

Butch Higdon, Texaco’s pump station supervisor, was hurrying out the door when Pigmon pulled up. “I don’t have time to visit,” Higdon said impatiently, heading for his truck. “I’m looking for a pipeline leak.”

“You just follow me,” said the rancher. “I’ll take you right to it.”

Five minutes later, the two men were surveying the rapidly growing black river. “Looks like I better get busy,” Higdon said. With that, he jumped back in his truck and sped down the bumpy caliche road toward the town of Wink, five miles away. Within a few hours, three bulldozers, a herd of trucks, and two dozen men were at the site, scrambling to contain the thousands of gallons of crude draining out of the 20-inch-diameter Texaco pipeline. The bulldozers built levees to contain the gushing oil. As the dozers worked to wall in the spill, two vacuum trucks sucked up the heavy-smelling crude. As soon as one truck was full, it turned around and headed for the row of huge gray oil tanks at the pump station. But there just weren’t enough trucks to keep up with the rising oil. Soon the levees gave way and the sulfurous oil crept over the arid terrain. Before the oil stopped flowing, six acres of Pigmon’s land—an area the size of four and a half football fields—was covered with oil.

Twenty-four hours after Pigmon found the leak, the pipeline was still draining. The welders and pipe fitters waited and watched as the oil occupying twenty miles worth of pipe oozed out onto Pigmon’s property. Finally, around noon, the damaged pipe was empty. Backhoes dug out the buried pipe, and the ruptured section was cut out. Seventy-four feet of new pipe were laid in place, and by six o’clock that evening, the welders were gone. The dozers leveled the dikes. The oil that couldn’t be vacuumed up was covered over with dirt. That done, the remaining crew loaded the equipment and drove away—leaving a chunk of Pigmon’s land oil-soaked and sterile. But the rancher didn’t know how much oil had spilled. No one from Texaco called him. So he waited. And when he learned two months later that nearly one million gallons of crude had leaked onto his land and was beginning to contaminate his groundwater, he got mad. And when Texaco offered him $1,200 for damages, he got a lawyer.

Having polluted water, a good lawyer, and a pending lawsuit against a major oil company has become a tradition in West Texas; Pigmon is just one of dozens of landowners fighting oil companies, which seem impervious to lawsuits and regulations. But this is only a modern extension of an ancient fight between ranchers and oilmen, one that was immortalized in Edna Ferber’s novel Giant. Bick Benedict was the noble rancher who loved the land; Jett Rink was the low-life wildcatter who plundered the surface to get to what lay underneath. Ranchers still see themselves as caretakers of the land, and they still believe—with good cause—that oil operators regard the land only as something that stands in the way of their objective. Much of the work of finding oil in Texas has been performed by high-living, free-spirited roughnecks who were not the sort to worry about a little brine here or a little oil leak there. Huge patches of West Texas have become oil-field deserts, because for years the salt water that is a result of oil production was released to flow across the land, leaving it bare.

Eventually oil-field carelessness shows up in the groundwater. The upper reaches of the Colorado River are being polluted with salt water from abandoned oil wells. Groundwater near the Odessa Petrochemical Complex is contaminated with cancer-causing benzene. Texas Water Commission investigators believe a refinery in the complex is responsible for a six-foot layer of benzene that lies on top of the local groundwater supply. Children in the El Ranchito subdivision, a few hundreds yards east of the refinery, can’t bathe in the water because it causes skin rashes.

Chemicals used during the oil-well drilling process often contain highly toxic elements, such as barium, chromium, cadmium, and arsenic. Drilling muds, corrosion inhibitors, workover fluids, and other oil-field materials are often dumped into unlined earth pits, spread over large areas, or used on oil-field roads for “dust control.” These toxic chemicals, which would be highly regulated if they were produced by any other industry, are exempt from scrutiny in the oil patch. In 1988 the staff of the Environmental Protection Agency recommended that oil-field waste products be regulated as hazardous waste. However, the staff was overruled by two appointees of Ronald Reagan: administrator Lee Thomas and assistant administrator J. Winston Porter. EPA officials have said that it was Porter who made the decision on the oil-field waste designation. At the time the decision was made, Porter owned an interest in two oil and gas wells in New Mexico.

The EPA estimates that about one million tons of hazardous waste are generated in American oil fields every year. The EPA has put seven Texas sites that are directly related to the production and refining of oil and gas on the federal superfund list. (The Texas Water Commission has put eight other sites that are contaminated with oil and gas wastes on the state superfund list.)

The watchdog for the oil industry in Texas is the Texas Railroad Commission, an agency frequently scorned by ranchers such as Pigmon for its laissez-faire attitude toward the problem of groundwater contamination. After the discovery of oil in East Texas at Spindletop in 1901, pipelines were deemed a mode of interstate transportation just like the railroads; thus began the Railroad Commission’s entry into the business of regulating the oil industry. Over the years, the commission has developed a reputation for being more concerned about production of oil than protection of water. For decades it has looked the other way while oil companies have disposed of salt water and dangerous chemicals on roads, in waste pits, and in creeks that flow into the Gulf of Mexico. Recently the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service started prosecuting oil producers because the pits that many of them use to dispose of waste oil attract—and kill—hundreds of thousands of migratory birds every year. During the course of their crackdown, agents have found hundreds of pits that are being used to store and dispose of waste oil. This use of open pits was legal until 1969, when the Railroad Commission finally adopted the “no pit rule.”

Despite numerous complaints about the Railroad Commission’s lack of environmental concern, the agency remains the sole arbiter in cases in which water has been contaminated by oil-field activity. Numerous landowners have appealed to the Texas Water Commission for help, but if its tests determine the pollution is coming from oil-field activity, the Water Commission can only turn the case back to the Railroad Commission. And even if the Railroad Commission wanted to pursue each contamination case, it doesn’t have the resources to do it. In 1989, $11.5 million was allotted for enforcement of state laws that govern Texas’ second-largest industry—not just pollution laws but everything from drilling permits to oil-field trucking. The City of Austin spends more money each year on parks and recreation—about $16 million—than the Oil and Gas Division of the Railroad Commission spends regulating the oil industry in Texas. About 5 percent—$1.02 billion—of the $21 billion 1989 state budget came from taxes the state collects on oil and gas. However, the state spends only .0005 percent of its annual budget to police the oil industry—an industry that sold more than $17 billion worth of oil and gas in 1988. In effect, oil-field pollution is virtually unregulated.

Water has long been more valuable in West Texas than oil. During the thirties after a boom in the small town of McCamey, a barrel of water cost a dollar. A barrel of oil brought five cents. Last summer in Midland, before Iraq invaded Kuwait, water was still more expensive than oil. The price of 42 gallons of crude oil—one barrel—hovered around $17. The price of 42 gallons of groundwater, based on the prevailing cost of 50 cents a gallon, was $21.

Half of all Texans rely on groundwater. In West Texas the percentage is much higher. In Winkler County, where Rex Pigmon lives, over 90 percent of all residents use well water. But in dozens of groundwater contamination cases, Railroad Commission investigators from the Midland office have blamed improperly cased water wells, fertilizer runoff, and septic tank leaks for water pollution problems. They have seldom blamed oil production.

In 1988 T. G. Herring, a rancher in Andrews County, had a water well on his ranch go salty. Tests on his water performed by the Water Commission indicated high levels of chloride, sulfate, and sodium—compounds commonly found in oil-field brine. Chloride and sodium levels in the water were nearly 12,000 parts per million—48 times greater than federal drinking-water standards. The Water Commission deemed the contamination to be oil-field related and turned it over to the Railroad Commission. Despite the Water Commission’s findings, the Railroad Commission determined the water was contaminated by “natural causes.” In the report, the investigator blamed the high sulfate levels in the water on sulfur mining. The closest sulfur mine to Herring’s ranch was sixty miles away. The closest oil well was just six hundred feet north.

The methods used by Railroad Commission investigators are as suspect as their findings. While testing Glenda Kiker’s water in West Odessa, an investigator from the Midland office tied a string to a dirty coffee cup to sample the contaminated well for bacteria—despite the fact that sterile bailers and containers are essential for proper results. When she saw her well being tested with a coffee cup, Kiker became furious. “I could see the coffee grounds in the bottom of the cup. What were they going to find—that my water’s high in caffeine?”

How many cases of oil-field pollution has the Railroad Commission uncovered in the Permian Basin? Mark Ehrlich, the complaint coordinator from the Midland office, says, “I haven’t found one case where groundwater has been contaminated by oil and gas activity in this region.” As for his use of the coffee cup, Ehrlich says, “There is no difference between testing with a sterile bailer and testing with a coffee cup”—a claim that Water Commission investigators greeted with a chorus of derisive laughter.

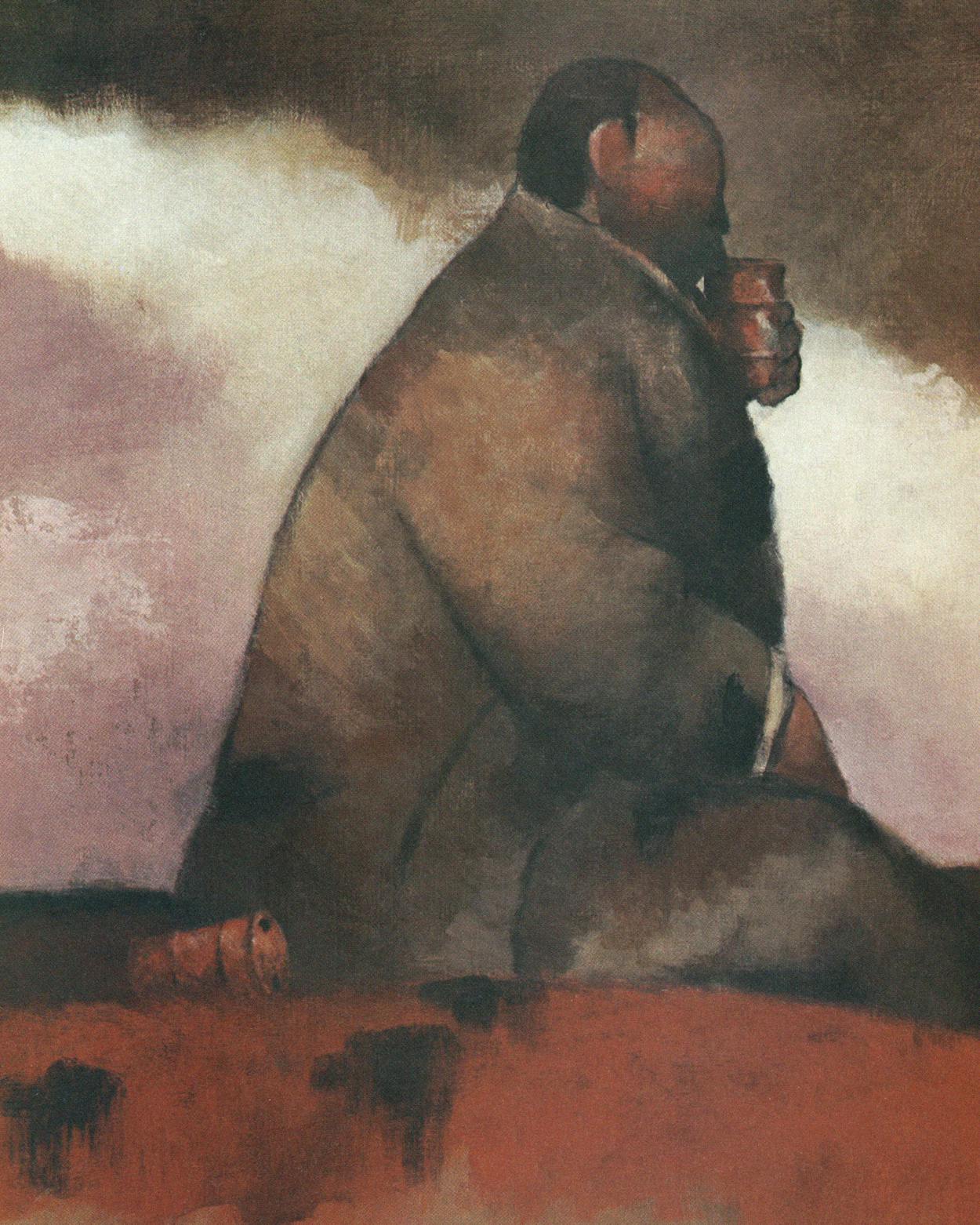

After about four years as a professional rodeo cowboy in the forties, Rex Pigmon returned to the ranch that was homesteaded a century ago by his grandfather Bill Vest. Decades of working long hours on horseback in the hot sun have left Pigmon’s arms and face a deep reddish-brown. A heavy-set, quiet man, Pigmon doesn’t waste words. He doesn’t like discussing the spill or dealing with the lawyers and engineers who are investigating the mess. If he had his druthers, he would just go quietly about his business, tending the eight hundred cattle that roam the sparse grassland. But Pigmon has seen the asphaltlike scars left by leaking tanks and pipelines. These leaks kill the soil and the grass. And in a dry region where each cow needs fifty or more acres of browse just to survive, every little bit counts.

Lying in the middle of the oil field that caused a boom in the town of Wink during the twenties, the 38-square-mile Vest Ranch has been explored for oil for six decades. Some four hundred active wells produce oil and gas on the ranch, and it bears the scars. Abandoned wells, barren drilling sites contaminated with toxic heavy metals, and rusting equipment litter the landscape. How much royalty income does Pigmon get from the oil pumped from beneath his land? Pigmon chuckles. “None,” he says. “My granddad sold all the minerals in 1918. We only get money for surface damage.”

Though he has worked around the oil industry all his life, none of his experiences prepared him for the trouble that began the day he discovered the Texaco pipeline break. Two months after the spill, when he hadn’t heard anything from Texaco Pipeline or the Railroad Commission, Pigmon decided to find out for himself what had happened. He looked up commission records, which indicated that on January 25, 1989—the day after the spill—Texaco Pipeline notified the Railroad Commission office in Midland that 3,200 barrels of oil had leaked from the pipeline and that 2,700 barrels had been recovered. Accepting Texaco’s version, the initial Railroad Commission report filed Monday, February 6, reads, “Operator cleaned up spill and replaced line. Oil spill affected about ¼ mile of land by 100 yards wide.” The following day, however, Wayne McClung, a field supervisor from the Midland office, went to the Vest Ranch. He surveyed the spill site and wrote, “Three feet of sand in low area oil soaked. Loss—23,534 barrels, Recovered—5,849, Net loss—17,685.” Neither report was even close to accurate. The leak Texaco had originally described as only 500 unrecovered barrels of oil turned out to be far worse. Nearly 20,000 barrels—about 750,000 gallons—of crude oil had soaked into the soil on Pigmon’s ranch and no one knew about it. None of the local papers carried the story. This was not like an oil slick at sea—no dead sea lions or oil-coated birds to be rescued—it was just a big greasy spot in the sandy West Texas soil. For six months after the spill, Railroad Commission investigators monitored how much oil had saturated the soil. They dug holes to see how much oil was flowing beneath the surface. When oil stopped flowing into the holes, they determined that the investigation was finished, filled in the holes, and closed the case.

The final field report on the spill was filed July 6 by Mark Ehrlich from the Midland office. Ehrlich’s report reads, “Mr. Pigmon stated that Texaco offered $100 an acre for the six acres damaged, and that for being such a cooperative guy they would pay him total of $1,200 for damage. Rex refused the offer to him, because he doesn’t know the long-term effect of the spill and that to him his land damage is about $250,000. . . . Texaco has not been very cooperative in contacting him about what is occurring on status of spill or the settlement. Rex would appreciate all the help we could offer to help him.”

Ehrlich was right. Pigmon needed help. But the Railroad Commission wasn’t going to give him any, and neither was Texaco. By July, Pigmon had found another commission report on the spill investigation. Dated June 28, it said, “On June 1, 1989, no more oil was seen within the monitor holes and it was decided that these holes should now be closed. Mr. Pigmon expressed satisfaction since there was no evidence of oil in the monitoring holes. The spill in question is underlaid by a very hard caliche layer and is not believed to be a threat to groundwater supplies. . . . As Mr. Pigmon appeared satisfied with the efforts, we believe no further action is necessary as this time.” Pigmon laughs when he reads the report. “I never expressed any satisfaction to these people,” he says. “They are just trying to weasel out of this thing.”

Contrary to the commission’s findings, the spill hadn’t gone away, and it was beginning to cause groundwater problems. A monitor well dug by Petro-Global Consultants, a Midland engineering firm, showed that two dangerous constituents of crude oil—benzene and toluene—were showing up in the shallow water table sixty feet below the surface. Petro-Global also gave Pigmon a rude shock when its consultants estimated that the cost of a complete cleanup on the site would be $9 million. The $1,200 offered by Texaco wouldn’t be enough to buy fuel for all the trucks and heavy equipment needed to remove the thousands of cubic yards of contaminated soil.

Two days after the spill, unknown to Pigmon, Chevron had hired Martin Water Labs in Midland to test a sample of fresh water drawn from one of Pigmon’s wells. The test wasn’t being done out of concern for Pigmon’s water resources; it was being done to determine if Chevron could use Pigmon’s fresh water for waterflooding an oil well on the Vest Ranch.

As oil wells get older and their productivity decreases, oil producers inject water under pressure to force more oil to the surface—an activity called secondary recovery. And though some companies use the salt water that is produced during oil production for waterflooding, many prefer to use fresh water. Unlike salt water, which is high in dissolved solids, fresh water doesn’t clog pipes and pumping equipment.

Nothing makes West Texas ranchers and farmers madder than the use of fresh water for waterflooding an oil well, and it doesn’t take them long to tell you why. Even if a farmer irrigates his crops on the hottest day of the year at high noon, the water stays in the weather system. If it evaporates, it later forms clouds and comes back in the form of rain. But if that same fresh water is injected into the ground for secondary recovery, it’s gone forever. Permanently polluted, it will stay in the oil cavity for eons, never to be useful again. In Texas in 1974, almost a billion barrels of fresh water were used for secondary recovery. In 1981, the last year for which accurate records are available, 600 million barrels of fresh water—enough to supply the city of San Angelo for nearly three and a half years—were flushed down oil wells. And while the Railroad Commission says it discourages the practice, ranchers like Pigmon are finding that oil producers are still using copious amounts of fresh water for secondary recovery.

Walter Bertsch has worked for the Soil Conservation Service in West Texas for 31 years and is now based in the small Gaines County oil-and-cotton town of Seminole, eighty miles southwest of Lubbock. He has seen hundreds of water wells drilled to provide fresh water for secondary recovery. In Gaines County alone, about 13 million barrels of fresh water a year are used for secondary recovery. More than 1,400 wells in eight West Texas counties—Winkler, Ward, Andrews, Gaines, Crane, Ector, Midland, and Martin—are currently using fresh water for secondary recovery. Three of the eight counties—Midland, Ward, and Winkler—have been designated critical water zones by the Texas Water Commission because of declines in the water table and subsequent shortages. Four more counties—Ector, Gaines, Andrews, and Crane—may soon be added to the critical water zone list. Despite declining freshwater resources, an antiquated law called right of capture governs groundwater usage in Texas. Based on English common law, it allows landowners to pump as much water as they want from under their land. Up until the twenties, the law also applied to oil underground. In those early days, oil wells were crowded close together and well owners competed to pump as much oil, as fast as they could, from the same pool. Since this depleted the reservoir needlessly, producers decided to apportion the production from a single oil field to the various owners. Unfortunately, this idea doesn’t apply to groundwater. Companies can buy land or water rights and pump as much as they like—regardless of the needs of neighboring ranchers and farmers who share the aquifer.

Bertsch thinks the use of fresh water for secondary recovery could be the death of agriculture in West Texas. “There will still be people wanting to live here after the oil is gone. And if there’s no fresh water, this area will dry up.”

Pigmon still fumes when he thinks about Chevron’s attempt to use fresh water for secondary recovery. The application Chevron filed with the Railroad Commission shows that the company planned to use 600 barrels of water a day to recover 37 barrels of oil. In other words, for each barrel of oil produced, 16 barrels of water would be permanently lost. Although Pigmon talked to Chevron representatives and was able to persuade them not to use the water, he is infuriated about the attempt—particularly because it happened so soon after Texaco’s pipeline spill.

“My uncle Earl Vest fought the oil companies all his life,” says Pigmon, “and I have fought them for most of my life too. These oil companies think us ranching people are kind of stupid country hicks that don’t know anything. But we put a stop to them using fresh water on that project damn quick. I wasn’t about to let them waste my fresh water.”

Pigmon figures more than a thousand oil and gas wells have been drilled on his ranch over the years. Some of them came in; most did not. Those operators who lost, Pigmon says, packed up their tools, threw their garbage down the deep, narrow hole that they thought would make them rich, and moved on.

Little did the old wildcatters know that the holes they were leaving across the state would cause so much concern today. Reaching thousands of feet into the earth, oil wells are essentially long vertical pipelines that allow oil to flow or be pumped to the surface. Very often, oil-bearing zones also have large saltwater formations in the vicinity. To prevent the deep salt water from traveling upward into freshwater aquifers near the surface, a well must be plugged with cement after it is shut down or if it contains no oil.

But of the 1.5 million oil wells drilled in Texas, approximately one million are left unplugged. Unplugged wells are particularly dangerous in the region around San Angelo because of the Coleman Junction, a highly pressurized saltwater formation that underlies the area. When oil wells are drilled through the Coleman Junction, the highly corrosive salt water begins to eat away at the steel pipe that lines the well. If the well isn’t properly plugged, the salt water eventually eats through the pipe and flows to the surface. One unplugged well, near the town of Rowena, northeast of San Angelo, spewed millions of gallons of salt water into the Colorado River for decades until it was plugged in the mid-sixties by the Railroad Commission.

A few miles east of Rowena, Runnels County farmer Ralph Hoelscher looks at the salt crystals lying atop the powdery soil that used to grow cotton and says, “My father-in-law worked this piece of land his whole life. And his father before him. This old soil is so salty now it won’t even grow grass.” Pointing to a nearby rise, the soft-spoken farmer explains, “There has to be an unplugged well right around here.”

Few people know more about unplugged oil wells in West Texas than Ralph Hoelscher. A self-educated expert on the problem, Hoelscher has been on a one-man crusade for ten years. He even ran for railroad commissioner a few years ago, losing narrowly to another Republican candidate, Jim Nugent, in the primary. When he is not tending his crops of milo and grain sorghum, Hoelscher is talking to other farmers and to anyone else who will listen about the danger of unplugged wells. In Runnels County alone, Hoelscher has found about one hundred unplugged wells. In neighboring Tom Green County, he has been working with Wayne Farrell, the director of the Tom Green County Health Department, to locate unplugged wells around San Angelo that are fouling the drinking-water supply. One was underneath the main street through town; two more were below O. C. Fisher Lake, which flows into the Colorado River.

Two reasons why so many wells in the state haven’t been plugged are the lack of enforcement by the Railroad Commission and carelessness on the part of the oil operators. Almost a century ago, the state Legislature mandated that abandoned wells be plugged. The Texas House of Representatives approved a rule in 1899 requiring operators abandoning a well to “securely fill such well with rock, sediment or with mortar composed of two parts sand and one part cement or other suitable material to the depth of two hundred feet above the top of the first oil and gas bearing rock.” In 1919 another law was passed that gave the Railroad Commission authority to enforce well-plugging. Despite these and other laws, thousands of operators simply left well holes open. Operators drilling on shoestring budgets had little incentive to spend more money on dry holes, especially when they knew that the Railroad Commission was unlikely to catch them. The penalties for not plugging wells were not severe and many operators declared bankruptcy to avoid liability. Compounding the problem of unplugged wells are inaccurate Railroad Commission records. Hoelscher and Tom Green County health inspector David Hale took me to numerous oil wells that had never been plugged—despite commission records that said they had been.

In late 1990 things began changing at the Texas Railroad Commission. New commissioner Bob Krueger ran television spots during the November election that emphasized the environment. Lena Guerrero, an Austin legislator appointed to the commission by Governor Ann Richards, has a history of environmental activism. The staff of the Oil and Gas Division has also been shaken up. Jim Morrow, the former head of the division, and Willis Steed, the former head of regulatory enforcement, have been replaced. After numerous complaints from the Martin County Underground Water Conservation District about an extensive saltwater leak that was ignored by the Railroad Commission, Ronald Strong, the director of the commission’s district office in Midland, was fired. Strong’s second in command, Hank Krusekopf, was demoted. Citing documents received under the Texas Open Records Act, Hank Murphy of the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal reported last summer that some of the workers in the Midland field office were accepting gratuities in the form of turkeys and hams from oil companies.

The new head of the Oil and Gas Division, David Garlick, told me that a new era of cooperation and vigilance has begun at the Railroad Commission. Even if Garlick can overhaul his division, the 101 field investigators spread among ten district offices face an industry of overwhelming size; 360,000 oil and gas wells are currently operating in the state—not to mention pipelines and abandoned wells—that should be checked periodically by commission investigators. The Midland office of the Railroad Commission may be the worst in terms of manpower. With more than 40,000 wells in the district, the office has only 9 full-time field inspectors.

The field offices are also responsible for regulating 364 natural-gas processing plants, thousands of miles of pipeline, and thousands of waste pits. Insiders at the Railroad Commission acknowledge that they are understaffed; one who requested anonymity said, “We could use five times as many field technicians as we have. And they would be busy all the time.” Garlick himself believes an increase of $5 to $10 million is needed to properly regulate the industry.

Former railroad commissioner Kent Hance agrees that the division needs more employees, but he believes a 10 percent increase in the budget will be enough. “I think we do a great job,” Hance said. “We could improve, but it becomes a question of money and whether the Legislature would give us that kind of money.” Fining operators that violate Railroad Commission rules could add money to the coffers, but the commissioners have shown extreme reluctance to levy large fines to get compliance from the industry. One of the highest fines ever levied by the Railroad Commission was $70,000 against Clinton Manges and the Duval County Ranch Corporation in 1984 for not plugging several abandoned wells. Compared to those of the Texas Water Commission, the Railroad Commission’s fines are minuscule. When the City of Houston violated wastewater regulations a few years ago, the Water Commission slapped the city with a fine of $500,000. Last spring the Water Commission levied a $244,000 fine against Formosa Plastics for wastewater violations at the company’s Point Comfort facility.

Despite personnel changes at the Railroad Commission, landowners—including Pigmon and Hoelscher—are still skeptical. And farmers and ranchers share a common sentiment: Having the commission watch over the oil industry is like having the fox guard the henhouse; landowners simply don’t trust the commission to do anything that will harm the most powerful industry in the state. While the oil industry has enriched the state treasury, the University of Texas, and many individual Texans, a legacy of the oil business—contaminated groundwater—will last long after the oil and the money have run out.

Pigmon’s white-faced Hereford cattle still drink the water brought up by windmills near the pipeline spill site. It is already too salty for humans to drink, and Pigmon figures even the cattle will soon quit. Wells that yielded fresh, clear water when he was a boy are now fouled with salt water and other oil by-products. To stay in the cattle business, Pigmon will have to drill a dozen new water wells, all of them at least 350 feet deep. At a cost of $10 a foot, the rancher figures he’ll have to spend $35,000 to reach the last remaining pocket of uncontaminated fresh water under his ranch. As for the lawsuit, Pigmon shrugs and says, “The lawyer told me he was going to take care of it, so I’m going to let him.”

Pigmon doesn’t have much to offer when asked how he would change the Railroad Commission or the oil industry. Taking off his hat, he wipes the sweat from his face. “You know, I don’t know. But something has got to change—that’s for damn sure. ’Cause without good water, I’m out of business.”

Robert Bryce is an Austin freelance writer who specializes in environmental issues.

- More About:

- Water

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- West Texas