This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

A flood is supposed to be an act of God, but the Great Trinity River Flood of 1990 was more an act of Man. This was a selective flood, inundating some while sparing others, acting not capriciously but in accordance with decisions made, over many years, by lawyers, developers, and politicians. Even before the waters reached their crest, the recriminations began. The poor who were wet blamed the rich who were dry. The downstream victims blamed the upstream interests. The people who lived on the river below the Lake Livingston dam—river rats, as they are called—blamed the Trinity River Authority for mismanaging the dam, and the TRA blamed the river rats for living too close to the river.

The flood began when the Dallas–Fort Worth area, which has an average annual rainfall of 29 inches, received 22 inches before May 1. Once that happened, the Trinity was certain to flood. But the amount of water in the river was multiplied by the works of Man: cities that covered the watershed and kept the ground from absorbing water, drainage pipes that rushed water into the river, levees that channeled the river and accelerated its current as it passed through. The worst flooding occurred not where the rain had fallen, but far downstream. Below Dallas, where the levees ended or gave way, the water spread out in great sheets, so wide in places that you could stand on one side and not see dry land on the other. Subdivisions near the river turned into deltas, with islands of rooftops surrounded by sloughs that used to be streets. On the Trinity River, the heavens brought the rain, but Man brought the ruin.

The long, mournful wail of a siren carried the bad news to the residents along the lower Trinity River seventy miles northeast of Houston. On top of the Lake Livingston dam a gray cogwheel started the process that would raise a steel floodgate and disgorge still more water from the lake into the surging brown sea that used to be the Trinity. When the wheel stopped turning on that warm morning in mid-May, the torrent of water cascading through the dam’s twelve gates exceeded 100,000 cubic feet per second, a rate that would fill a reservoir the size of Lake Houston—nineteen square miles—in just sixteen hours.

The crest of the flood was passing through the dam, but the river had been in and out of its banks all spring. The Trinity does not flash flood like the rivers in the drier part of the state; it tortures rather than kills, creeping over its broad floodplain and occupying it for days that can run into weeks. The part of the flood that made national news followed the upstream rains of late April and early May. The water roaring through the dam would soon saturate empty homes formerly occupied by six thousand people.

I could feel the dam pulse and shudder beneath my feet, and I was relieved to see that the dam inspector from the Texas Water Commission looked unconcerned as he peered over a railing. From deep inside the superstructure came muffled rumbles like thunder, caused by water smashing into the gates. Through a grate I could look down into the bowels of the spillway, where a violent whirlpool, so wide that its full extent escaped the eye, sucked water into floodgate number three.

On the downstream side of the dam the Trinity was in full boil. The released water was constrained between two concrete training walls, perpendicular to the dam and about five hundred feet apart, that extended a short distance downriver. The walls and the dam formed a three-sided basin within which everything was chaos. The water had no surface, only a patternless, frothy turbulence of waves, currents, backwashes, and geysers. Spray shot twenty feet into the air. This frenzied action is known as hydraulic jump. It is caused when water spewing from the dam crashes into submerged concrete blocks that rest on a concrete floor between the training walls. The object is to make the falling water expend its energy close to the dam, where the concrete apron can protect the river bottom. Without the blocks, churning currents would dig a hole in the muddy bottom beyond the basin, undermining the dam and causing it to slide in.

Behind the dam, the scene was entirely different. The lake was under control, still obedient to the engineers and lawyers who determined its maximum level long ago. The subdivisions along the lakeshore remained high and dry. But a quarter of a mile below the dam, waves lapped at second-story windows in a riverfront development, and at Liberty the Trinity was higher than it had ever been, breaking the record set in 1942 before the dam was built. The Lake Livingston dam—like more than a dozen others far to the north, like two hundred miles of levees along the river—has not been able to conquer the Trinity. Those devices have only shifted the misery downstream.

The Trinity River Basin is shaped like a dancer’s leg, with the foot arched and the toes pointing into Galveston Bay. The river is formed by three forks that merge west and east of Dallas, but the headwaters start a hundred miles west of Fort Worth and as far north as six miles from Oklahoma. Reservoirs large and small surround the Dallas–Fort Worth area, but below the confluence of the three forks, the river runs free, through gently rolling farmland to Lake Livingston. Here the Trinity River basin narrows—the leg’s ankle—and enters the East Texas forest. Below the dam the shoreline is punctuated with subdivisions, all the way to the flat rice-farming country below Liberty.

The Trinity has inspired more schemes and less love than any of the major Texas rivers. It cannot rival the Brazos, the Colorado, and the Guadalupe for beauty, nor the Rio Grande, the Nueces, and the Red for historical importance. Only as an organ of commerce has the Trinity compared favorably. Early settlers regarded it as our Mississippi—the river through the state’s heartland that could be made suitable for navigation, industry, farming, anything its masters determined. Nothing so clearly indicates the prevailing Texas attitude toward the Trinity as a short-lived project in the 1870’s to stock the river with . . . salmon.

The trouble with the Trinity was that it always seemed to have too much water or too little. It could flood for weeks in the spring and then go dry in the summer; and when it flooded, the water escaped over the flat prairies for miles. It was a fickle and deceitful river that never quite lived up to its promise. Not too many years passed before three very different cultures came into being along the river, three different ways of regarding the Trinity that persist even today. The builders were represented along the entire river, but nowhere were they as dominant as in Dallas. They were determined to make the river into a useful thing. But there were other people who knew the river and were willing to live with it as it was. They farmed the bottomland, but they knew better than to build their towns there; to this day there are no cities on the Trinity between Dallas and Liberty, a distance of 550 river miles. And finally there were those who were new to the river and didn’t know it at all.

The builders wanted the Trinity to be navigable year-round as far upstream as Dallas. The plan already had wide support in the basin by 1852, when a lieutenant from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers inspected the Trinity and proclaimed it the clearest and least obstructed river in Texas. But the people who had to live with the river knew better. “It is said to be the best stream in Texas for navigation,” an early farmer wrote in his journal, “but this I cannot agree to. It is at every place I have seen it entirely obstructed with timbers which are still and always will be falling in.” It was easy for a newcomer like the Army engineer to be fooled. Even Mirabeau B. Lamar, seeing a fertile prairie about four miles wide, thought of settling on the Trinity in 1835, but had the good sense to ask the locals first. “I found on inquiry that the whole tract was subject to inundation,” he noted in his journal, and moved on.

Because it was on the river, Dallas had the most to gain by changing the Trinity and, being flood-prone, the most to lose by not changing it. In 1902 the builders succeeded in getting Congress to approve turning the Trinity River into a canal. A few rudimentary locks were actually built before the project ran out of money. The builders had more success in doing something about the Trinity’s frequent floods. After the flood of 1908, with its 52-foot crest that still ranks as the highest in Dallas’ history, local officials turned to a city planner named George Kessler to tame the river. Kessler produced a plan to straighten the Trinity and to contain it within high levees. Skeptics claimed that the project cost too much and might not work, but Dallas was Dallas even then, and Kessler carried the day by saying, “You will never establish a city under the feeling that you can not do things.” When the work neared completion, the Dallas Morning News ran a front-page picture of the 1908 destruction with the caption, “Flood scenes such as this will shortly disappear.”

But they didn’t disappear; they just moved. Dallas grew southward, down the river, past Kessler’s levees. There the pent-up river found its release, regularly driving poor people, mostly blacks, from their homes in the unprotected floodplain. The builders put dams on each of the three forks, creating huge reservoirs that would not only contain floods but also provide drinking water so that the area could continue to grow. To no avail: The Trinity kept on flooding. The solution? More dams and more dams, until there were eighteen in all on the three forks and their tributaries—and still the river flooded. Every time a new dam held water out of the Trinity, growth put water right back in: With every foundation that was poured, with every street that was paved, with every drainage pipe that was laid, water that might have been absorbed by the ground ran off the impervious cover straight into the river. Northwest of downtown Dallas, developers remade the floodplain into an industrial district: one more place that the water couldn’t go. Where it did go was downriver. The Dallas George Kessler had saved was still safe, but downriver the Trinity was more vicious than ever.

Folks around here know the river,” Gene Reynolds said. ”It always has flooded and always will. Comes a big rain, water’s gonna get on ya.”

Reynolds was wearing jeans with a snakeskin belt and a white work shirt with a scene of a duck flying out of a marsh embroidered on the left pocket. We were standing on U.S. 287 between Corsicana and Palestine, two miles from the Trinity River bridge but two feet from the Trinity River. A dark watermark on the back of a yellow “Drive Friendly” sign showed that the river had gone down about two feet. At its crest, the flood had swept over a nearby oil-field dike, built to keep spills in rather than the river out; seven Texaco storage tanks were surrounded by water that could not escape. Reynolds looked at two fishermen seining for crawfish in an inundated ditch and shook his head. “Fishing’s no good in a flood,” he said. “The fish are off feeding in the fields. The best fishing is right after the river gets back in its banks.”

Reynolds embodies the attitude of the middle section of the Trinity, between the three forks and Lake Livingston, where the people most interested in the river are not the builders but serious fishermen like himself. No dams block the main channel; no reservoirs attract weekend boaters. Almost no one lives on the river itself, and there are local legends about those who have tried, only to see their houses swept into the river. The moral of such tales is that the river is better off being left alone.

In his late thirties, Reynolds lives in Fairfield, a town that is located a respectful distance from the river. He dropped out of law school to become a petroleum landman because he didn’t want to spend his life indoors. He has been drawn to the river ever since he can remember, but he has no romantic illusions about it. “You can’t take a fiberglass boat on this river,” he told me. “It’s full of hidden tree stumps. They’d tear it up in a minute. You can’t take a V-hull boat out there either. It can’t maneuver in the currents. About all you can use is a flat-bottom aluminum boat.

“At least there are fish in the river now. When I grew up, unless you just enjoyed going out in a boat, there wasn’t any use in going fishing because there weren’t any fish. Sewage from Dallas used up all the oxygen. I can still remember the stink. I used to think that was how a river was supposed to smell.”

Reynolds and I drove on high ground to the Richland-Chambers reservoir, formed by two creeks that empty into the Trinity. From the dam, Reynolds pointed to a small knob on the horizon that poked above the tree line. “That’s where my river house is,” he said. ”I was in Palestine at a meeting of folks interested in saving the river when a real estate agent told me about it. I got him to take me out there right away. As soon I saw it, I said, ‘Take it off the market.’ You don’t find high ground on the Trinity every day.”

At the height of the 1990 flood on the lower Trinity, the general manager of the Trinity River authority stood on the Lake Livingston dam and tried to explain his agency’s response to the flood. “We are trying to simulate the flow of the water as if the dam did not exist,” Danny Vance said. As if the dam did not exist? How could the officials responsible for the river ignore the only possible defense against the onrushing waters? The answer is that whatever chance the Lake Livingston dam had of controlling a major flood on the Trinity River had ended long before 1990—before, in fact, the dam was ever built.

Lake Livingston was the prize in the last big water-war in Texas, fought in the fifties between Dallas and Houston. Dallas wanted the proposed reservoir to help fulfill its old dream of a Trinity canal. The lake would ensure that there would always be enough water for navigation in the lower Trinity. Houston wanted the reservoir to be a future source of its drinking water. In 1959 the two cities filed rival requests with the Texas Water Commission to build the Lake Livingston dam. In a last-minute deal, Houston received the rights to 70 percent of the water in the reservoir. The other 30 percent belonged to an obscure governmental body just four years old—the Trinity River Authority.

River authorities are state agencies, but they are not what Lincoln called government of the people, by the people, for the people. They are old-fashioned political fiefdoms; their boardmembers are appointed by the governor, but otherwise they answer to no one. They build reservoirs and sell the water in them. The TRA also builds and operates sewage-treatment plants for cities in the basin. River authorities make their own money, set their own budgets, and do as they please. They have vast constituencies—more than four million people live in the Trinity basin—but the public has neither vote nor voice in the decision-making process, even over such crucial issues as how to operate a dam during a flood.

Flood control, however, was not the TRA’s reason for being. Prospects for the Trinity canal had taken a turn for the better in the fifties. In Washington, Senator Lyndon Johnson prodded Congress into declaring that the Trinity should be controlled from the source of its tributaries to its mouth. In Austin, the Legislature created the TRA to build the canal. In Dallas, a group called the Trinity Improvement Association, formed to promote the canal, publicized the fact that the region was the largest metropolitan area in the country without a port. Soon TIA boardmembers like Southland Life chairman Ben Carpenter won appointment to the TRA board as well.

Lake Livingston would help make the river navigable. But what kind of lake would it be? A flood-control reservoir requires extra storage capacity above the normal water level. Because so much additional land must be purchased, flood-control reservoirs typically have been funded by Congress. A smaller water-supply lake, however, could be financed by the TRA by issuing bonds and paying them off with water sales from the reservoir. All of the groups involved in Lake Livingston favored the second option. The canal backers in Dallas were interested in navigation, not flood control hundreds of miles downriver; in any case, they weren’t about to delay the project by waiting for federal funds that might never arrive. Houston, which wasn’t even in the Trinity basin, had no stake in flood control. Downstream rice farmers, who depended on a steady flow in the Trinity to prevent salt water from invading the river channel, wanted the reservoir built as soon as possible. Influential land speculators wanted a lake with a developable shoreline, not an empty space reserved for flood control. The TRA had been created to build, not to protect. The issue was settled. Lake Livingston would be a water-supply reservoir. It was never intended to be used for flood control—a fact unknown to thousands of people who bought downstream riverfront property.

The new lake’s elevation was set at 131 feet above sea level. The TRA bought a flood easement from lakeside property owners, giving the TRA the right to raise the lake to 134 feet. But that was all; Lake Livingston could go no higher. If it did, Houston and the TRA would be subject to lawsuits by landowners on the lake. Moreover, the dam itself, designed to top out at 145 feet, would be at risk.

The canal plan called for another dam upriver at Tennessee Colony, west of Palestine, that would provide flood control. But it was never built, even though in 1965 Congress finally approved making the Trinity navigable. The fate of Tennessee Colony foreshadowed the changes taking place in Texas politics—the decline of the all-powerful business establishment and the rise of the two-party system. The once-solid support for the Trinity canal had begun to erode as early as 1962, when the Republican candidate for governor against John Connally came out against the canal because of its cost. Later, an organization called COST—Citizens for a Sound Trinity—opposed the canal on environmental and fiscal grounds. For once the TRA couldn’t avoid an election. It had to ask voters along the river for the power to tax in order to pay for its share of the navigation project. In March 1973, 54 percent of the voters said no. The downriver counties split, but Dallas, the city that George Kessler had warned would never get anywhere with a can’t-do attitude, voted resoundingly against what a Republican critic called the “billion dollar ditch.” The TRA continued to press Congress to fund Tennessee Colony, but when the energy crisis drove up the price of buying out lignite operators at the proposed reservoir, the cost of the project far exceeded the benefit. In 1977 the Carter administration included Tennessee Colony on a hit list of water projects, and the last vestige of the canal was dead. The Trinity River still had no flood-control reservoir below the three forks. When the 1990 flood arrived at Lake Livingston, the dam was useless.

To cross the Trinity River bridge at Liberty, 43 miles below the dam, took an act of faith. The river had risen to within an inch or two of the bottom of the bridge. Small logs, barely more than sticks, couldn’t pass underneath. To the north I could see workers trying to repair a flaw in the railroad bridge that had halted traffic on the Southern Pacific main line. By my car’s odometer, the river was 3.7 miles wide.

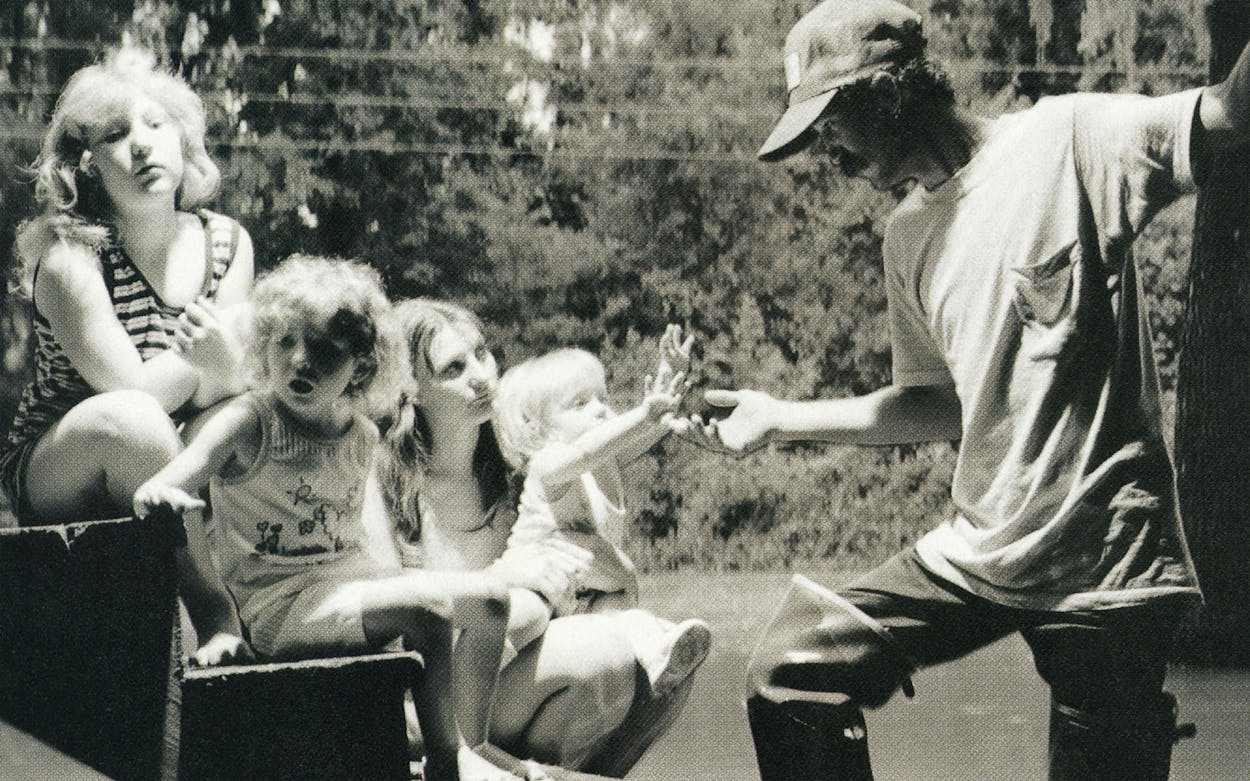

Liberty itself was dry; the problem was the subdivisions that stretched north of town all the way to the dam. Most of them were right on the river. They had names like Knight’s Forest, Horseshoe Bend, and Sam Houston Lake Estates, but they were not as elegant as their names suggested. Many of the homes had started out as makeshift weekend cabins that their owners had personally enlarged into permanent residences. There were mobile homes and small retirement cottages and a few places with real money in them. Around eight thousand people lived in the flooded subdivisions. Most residents had scattered across the area, staying with friends or relatives and returning occasionally by boat to check out their swamped houses. The roads leading into the subdivisions were lined with pickup trucks right up to the waterline. Neighbors sat on coolers, smoked cigarettes, drank beer, swatted gnats, and waited for the next boater to return with news.

The subdivisions began to appear in the early sixties, soon after the dam was announced. The king of the subdividers was the late Barney Wiggins, a county commissioner in upriver Polk County. “He bought every piece of river bottom he could get,” a veteran Liberty real estate agent named Bubba Van Deventer told me. “He sold the lots and put in substandard roads. Very few folks from around here bought. They knew better.” But people from Houston were lured by the promise of cheap land on the river. They knew nothing about the Trinity and its habitual flooding. (One lot buyer, according to local lore, plunked down his money after being told that a high watermark on a tree was really made by wild hogs scratching their backs.) Some buyers saw the land as a weekend getaway. Others saw it as a retirement site. Many purchased the land as an investment.

Now they are all stuck. The residents of the subdivisions, mostly blue-collar or retired, can’t afford to pick up and leave, nor can they afford to sell—Bubba Van Deventer told me about an FDIC foreclosure posting of a cabin and two lots for just $2,000. Most residents don’t want to move; they still love the river that regularly betrays them. What they really want is for the flooding to be held in check, and they are looking for someone to blame. That search quickly leads to the Trinity River Authority. “This is all preplanned,” a weathered, bearded river rat named John Allen told me. “They still want to build that canal, and they’ve got to get us out of here first.” His stepson, a redheaded boy of about twenty, joined in. “They’re flooding us so that the marinas up on the lake can have their bass tournaments,” he said. “We got a right to live on the river too.”

What the subdivision residents want is for the TRA to change the way it releases water from the dam. In calculating how much water to release, the TRA considers only what is happening on Lake Livingston itself: The lake level, the inflow from the river, the wind direction, and the rainfall on the lake during the calculation period determine the discharge rate. The formula is the same whether the river around Dallas is flooded or dry. If a flood is on its way, the subdivision residents say, why not release water in advance, lowering the lake level so that less has to be released later? A release of 20,000 cubic feet per second is the most that can be discharged without causing a flood; yet, in late April, with a massive flood on the way, the TRA was releasing less than 20,000 cfs. A prerelease of 40,000 cfs during that period—a moderate flood that would have closed most roads into subdivisions but would have allowed many residents to remain in their houses—would have taken around a fourth of the water out of Lake Livingston. That would not have prevented the flood. In the first three weeks of May, enough water passed through the dam to fill the entire lake. But it would have diminished the flood; it would have kept the railroad bridge open; it would have kept the river from inundating places that had never been flooded before. The TRA argues that a big rain during prerelease would cause a major flood. Perhaps, but so did the failure to prerelease.

The subdivision residents have found a supporter in Liberty County judge Dempsie Henley. Six and a half feet tall, with wavy hair and a moustache, Henley takes issue with the way the TRA releases water from the dam; it’s either too much or too little. “I was born and raised on the river,” the 66-year-old Henley said, “and it’s a different river now. Floods are a way of life here. People would move when the water came. But it never came like this.” Back in the sixties Henley owned some property on the Trinity. He sold part of it to a Florida developer and on the remainder put in a subdivision himself. “I thought people could live with the floods,” he said. ”I thought they’d put up rec homes and come for the weekend. They retired here instead.” He smiled ruefully. “To be honest with you, I thought I’d get in on some of that money.”

On April 26, as the flood headed down the Trinity toward Lake Livingston, Henley brought the TRA and around three hundred flood victims together in a Liberty meeting hall. Danny Vance presented statistics on rainfall and stream flow, but the subdivision residents weren’t persuaded. They had their own ideas about what the TRA should do—starting with having their boardmembers elected. In a memo to TRA boardmembers, Vance wrote, “You will not be surprised to learn that the public meeting in Liberty was about as pleasant as a root canal.”

The flood is off the newscasts now, but it isn’t over. The record crest has poured into Galveston Bay, making the mix of water in the estuary so fresh that there will be a meager oyster crop this year, but behind it, the Trinity remains out of its banks all the way upstream to the three forks. U.S. 287 reopened, then almost closed again in early June after heavy rains sent the river up. Farms and fields above Lake Livingston are still submerged. All of that excess water must eventually find its way into the lake and pass through the dam, where the release rate will continue above 30,000 cfs into midsummer. Subdivision residents will not be able to drive back to their homes until late June, if then. After all that water has made its way to the sea, a volume of water equivalent to Lake Livingston must be drained from the flood-control reservoirs around Dallas. The river will not return to normal flow until the fall. Then there will be a few brief months of tranquillity on the Trinity, a time to hunt and fish and watch the river flow by, until the cycle begins again, and the people along the river will cast a nervous eye to the sky and wonder when, not if, the river will flood again.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Flooding

- Houston

- Dallas