A lot has happened since October 1, 1974, my first day of employment at Texas Monthly. I remember the unbridled joy I felt joining the magazine and leaving behind the Texas Senate after several years of working as a staffer. No more bills to draft, no more reports to write, free at last. The magazine’s original offices, at Fifteenth and Guadalupe, in downtown Austin, were located up a flight of stairs, above a finance company. A dental lab sat across a tiled vestibule from our quarters. In the back, above an alley, a laundry belched the aroma of ammonia through an open window into our meager work space. All of us owed our employment to our publisher, Michael R. Levy, whose father, a plumber who had emigrated from Poland, had helped him start Texas Monthly the previous year. The staff was small but close-knit. Several, like me, were escapees from the Legislature—Levy, Griffin Smith Jr., and Richard West. Smith and I, along with the magazine’s first editor, William Broyles, and another writer/editor, Gregory Curtis, had all been friends at Rice University and had written for the Rice Thresher, which was not, it is fair to say, the apotheosis of collegiate journalism.

We loved Texas, and we loved what we were doing, and the entire state was our beat. Texas was a very different place back then: I once described it as an urban state with a rural soul. No one was looking at our institutions with much skepticism—the newspapers were mostly terrible—and so we had nearly unlimited chances to try to define and shape the future. I never imagined, of course, that I had found my life’s calling, or that my career would extend for forty years. All I knew was that my colleagues and I were embarking on a grand adventure.

We didn’t really know how to put out a magazine, but we knew a good story when we found one, and we knew how to put words and paragraphs together. In fact, Texas Monthly won a coveted National Magazine Award its first year out. My debut was a story about Clark Field, the iconic baseball park where the Texas Longhorns once played their home games. The team was great in those years, before college baseball became a major sport, but what made the ballpark truly memorable was a sheer rock cliff that had been blasted out of center field and flattened out on top. Outfielders had to scale the cliff like goats in order to reach the ball. The legend of Clark Field is that when Lou Gehrig and the Yankees came for an exhibition game, in 1929, Gehrig hit what the Los Angeles Times would describe as “without a shadow of a doubt, the longest home run ever hit by man in the history of baseball.” It landed on the lawn of a fraternity house and was estimated by the Times to have traveled nearly six hundred feet. For writing about this venue, I received my first check from Texas Monthly—$75 for a story aptly headlined “At Play in the Fields of the Lord.” I could call myself a writer.

But, soon enough, I found myself back at the Legislature. I just couldn’t tear myself away. It was true then that the Lege represented much that was good about Texas and, sadly, much that wasn’t. That remains true today. Politics has always been more about personalities than the details of public policy, and these characters were irresistible. Smith, Broyles, West, and I wanted to write about the way they shaped our state, for good and for ill. The question was how to do it. And so was born the Best and Worst Legislators story, which has been a staple of Texas political journalism ever since. Other magazines had done “Worst Members of Congress” lists, but it was Broyles who had the wisdom to include a Ten Best list along with a list for Ten Worst.

In those early days, virtually the entire membership of the Legislature was made up of conservative Democrats. There were three “parties”: liberal Democrats, conservative Democrats, and Republicans. The R’s then were few in number, stayed on the sidelines, and watched the two groups of Democrats fight, just as mainstream and conservative Republicans battle it out these days.

Among my favorites were feisty A. R. “Babe” Schwartz, for whom I had written those turgid reports in the Senate, and Ray Farabee, an all-time great senator renowned for evenhandedness. There were also folks like A. M. Aikin Jr., chairman of the Senate Finance Committee and an author of the Gilmer-Aikin Laws, which funded public schools; the august Barbara Jordan, at the top of her game; and “Timber Charlie” Wilson, a world-class playboy who protected the Big Thicket before he started supplying Afghan freedom fighters with Stinger missiles to drive the Russians out of Afghanistan. All of these lawmakers are gone now, except Schwartz, who survived a stroke but had to have part of his brain removed in the late eighties. Afterward, Schwartz would go around telling folks, “My doctor said I didn’t have enough of my brain left to practice law, but it was all right to lobby.” (He’s 88 now and still going strong.)

But it wasn’t just our coverage of the Legislature that changed journalism in Texas. Broyles authored the history of the King Ranch. Smith wrote about the “Big Three” Houston law firms and their associated banks that dominated the city’s business and financial life. Prudence Mackintosh revealed the secrets of sorority life at the University of Texas, and those of her own family, endearing herself to readers forever. Gary Cartwright wrote an amazing story about the hard life of an aging, down-and-out cedar chopper and his family, who lived in their station wagon for the better part of two months, waiting for their welfare check to arrive. There are many other Texas Monthly writers who deserve similar accolades, such as the late Bill Porterfield, who wrote, in his “Farewell to LBJ,” of the president’s funeral, “The way we stood in concentric circles reminded me of the circles of life in a fallen oak, with the dead man as our common core.”

Texas Monthly has always been the kind of place where everyone pitched in, and I often did double duty as an editor. Editing requires a different skill set: the skepticism of an attorney and the patience of a diplomat. I may not have always demonstrated those abilities, but it was fulfilling to help young writers like Mimi Swartz, Jan Jarboe Russell, and Patricia Kilday Hart (who wrote our first profile of George W. Bush), and then later Pamela Colloff, John Spong, and Katy Vine. I was particularly honored when Greg Curtis, the magazine’s second editor, asked me to take charge of the issue that celebrated the state’s sesquicentennial, in 1986. The magazine we produced went well beyond the tired Texas myths to present a social history that was deeper and truer than much of what had gone before. Every great Texas writer was in that book, from the Barthelme brothers to Larry McMurtry to Molly Ivins, and if you have trouble locating a copy, you can find it listed forevermore in the Library of Congress.

My career took a new turn in 2006. Our editor at the time, Evan Smith, decreed that my job description would be expanded to include blogging. My initial reaction was that I had been demoted. In fact, my new assignment would open the digital world to this old-school Luddite. I had some trepidation in the beginning, but then I realized that I had a fantastic platform: I could be critic and audience of Texas politics, engaging in debates with my readers and responding to their criticism of my work (of which there was plenty). And I could do it all in a twinkling; when I heard that UT president Bill Powers was in danger of being fired, I could post that scoop in seconds, instead of waiting for the next monthly issue.

Still, it’s the print stories I will remember most, and not necessarily the reporting I did on tough customers like Oscar Wyatt, Arthur Temple, and Clinton Manges. My biggest coup was getting the first interview with Laura Bush after she became first lady, in 2001. We met in the Map Room of the White House, where FDR had followed the progress of World War II in Europe. She was warm but reserved, revealing just enough of herself to tug at the readers’ heartstrings. “The hardest part for me,” she said near the end of our interview, “is that the children [her daughters, then away at college] don’t think of Washington as home. . . . I hope they realize how much their mother misses them.” At that moment, she wasn’t Laura Bush, first lady, but Laura Bush, empty nester.

Alas, time does not stand still, and I have decided to move on. This issue marks my last as a full-time staff member, though I will still help cover the Legislature this session. I wish I could say in parting that the twenty-first century has been good for Texas politics, but I can’t. If Texas politics once produced giants, our time seems more like the dark ages. There are no John Connallys or Ann Richardses or Bob Bullocks. These were people who loved Texas and, because of that love, knew how to reach across the aisle, set their egos aside, and put the best interests of the state first.

But then came fourteen years of Rick Perry, a governor who seldom exhibited much interest in government. In Rick Perry’s Texas, everything was about Rick Perry. He lived like a king, traveling around the country (and for that matter, the world) with a retinue of DPS troopers. He double-dipped on his salary, combining it with his pension. He cared more about handing out favors to his friends than making Texas a better place. What did he do for us? His main contribution was using state money to lure businesses to Texas. I don’t fault him for that, but many folks, myself included, thought Perry used the deal-closing Texas Enterprise Fund, as it was known, as a slush fund.

His biggest humanitarian act in office may have been to welcome the refugees from Hurricane Katrina. But more often he could be found hurting Texas’s most vulnerable people: cutting thousands of kids from working-class families from the Children’s Health Insurance Program so he could balance the budget in 2003, for instance. Just a few years ago he refused to expand Medicaid, which will in due course cost the state billions in federal funds. He should also have to answer for assembling the worst UT System Board of Regents in recent memory, and for doing everything possible to wreck UT-Austin’s reputation and financial stability.

Perry is not to blame for all the state’s problems, but I do hold him responsible for the ugly political culture that exists today, one that is more like the angry, polarized Washington, D.C., he claims to loathe. Who is there to defend the Texas I used to know? At this point, I would welcome the return of former governor Bill Clements, an archconservative, yes, but one who looks like Winston Churchill by comparison.

I am reminded of an aphorism that former state legislator Bob Eckhardt, who held office back in the fifties, liked to say about Texas politics: “The Capitol was built for giants but is inhabited by pygmies.” That remains the perfect epitaph for the Legislature today. The pygmies are in control.

A long time ago, around the arrival of the twentieth century, folks in Texas put to song a cowboy doggerel about the unwanted changes that were taking place in the state.

I’m going to leave old Texas now.

They’ve got no use for the Longhorn cow;

They’ve plowed and fenced my cattle range,

And the people there are all so strange.

Sorry to say, the same applies today.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

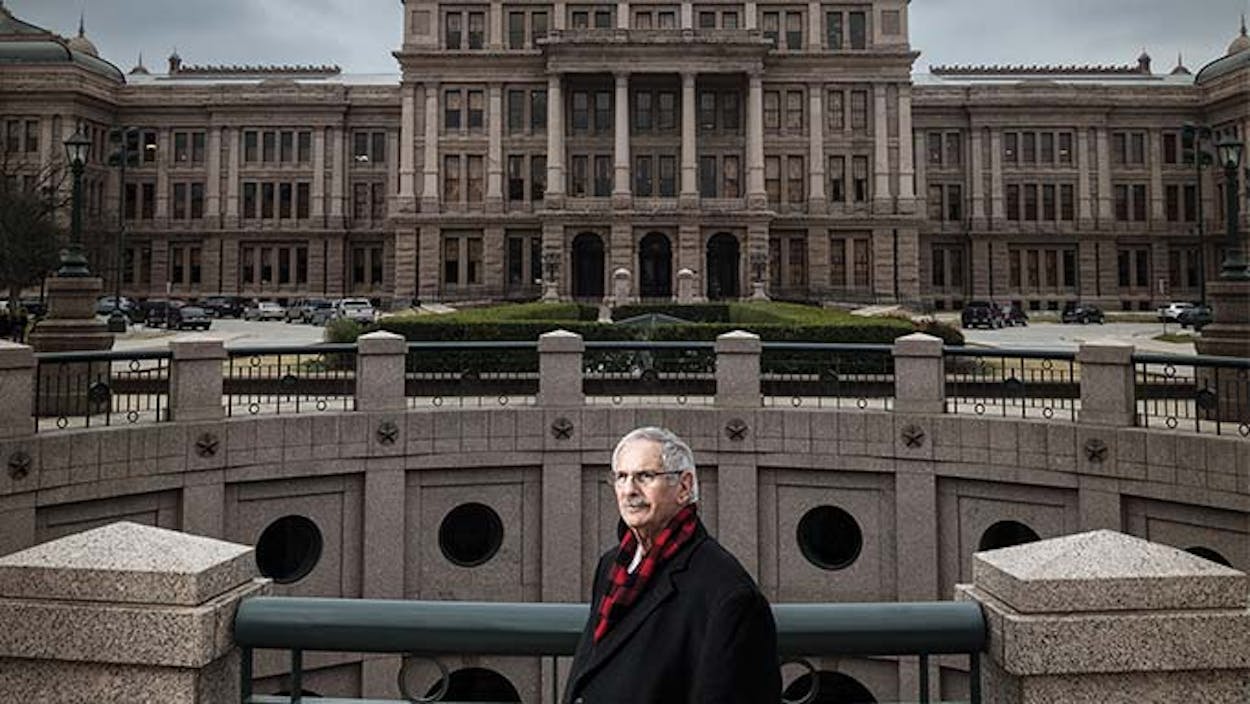

- Paul Burka