“I’ve got a photo of Burka in my office that I cherish,” said former state representative Steve Wolens in a recent phone call, referencing former Texas Monthly senior executive editor Paul Burka, the longtime, universally acknowledged dean of the Texas Capitol press corps. “He’s at his customary spot at the back rail in the House listening to Representative Garnet Coleman, kind of bent over his reporter’s notebook, just scribbling. Garnet’s there, telling him whatever he had to tell him, with a bunch of members huddled on the side, waiting for their time to talk to Paul. It’s such a great photograph, perfect for showing Paul’s influence in the Legislature.”

Those are the kinds of memories that came gushing from old pols in the days after Burka’s peaceful death on August 14 at age eighty. For nearly forty years, he was a fixture at the Capitol and the lead author of the magazine’s biennial Best and Worst Legislators list, his byline appearing on the franchise’s second edition in 1975 and continuing through his last session covering the Lege in 2013. From the start, he established himself as a fair-minded voice of authority—as someone who celebrated acts of true leadership but fired sharp darts at elected officials who pursued their own gain rather than Texas’s. Karen Hughes, a key adviser to George W. Bush when he was governor and president, was a political reporter for Fort Worth’s NBC affiliate, KXAS-TV, when she first got to the Capitol during Burka’s second session, in 1977, and she said he was already viewed as the guru. “Just by being there, by holding people accountable,” she added, “he made a generation of political leaders better than they otherwise would have been.”

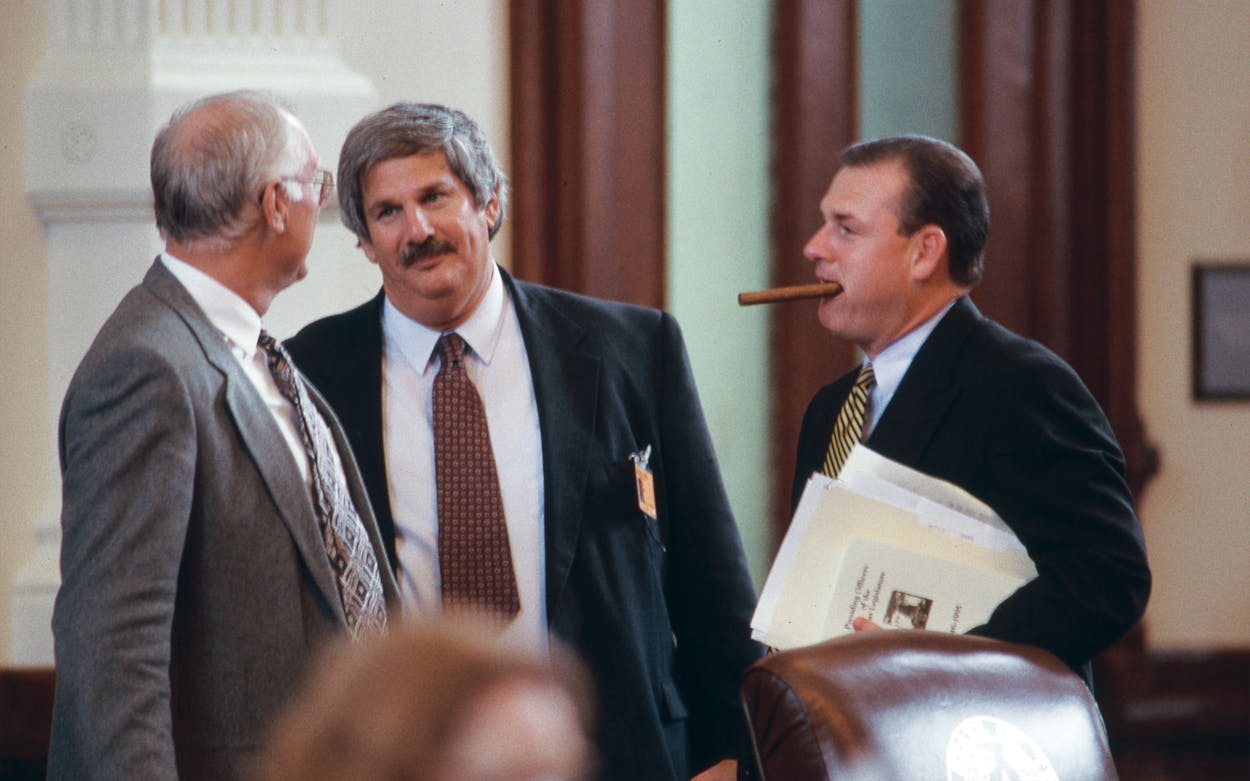

Former Republican governor Rick Perry, first elected to the House as a Democrat in 1984, described his initial impression of Burka. “I was a boy legislator, and he was bigger than life,” said Perry, a product of tiny Paint Creek, halfway between Lubbock and Fort Worth, who’d go on to run twice for president before serving three years as U.S. secretary of energy. “When he showed up in the back of the chamber, people would start straightening their ties and clearing their throats as they headed to the back mic. He was the ringmaster, really.”

“The Best [Legislators] list was the Academy Awards for the Lege,” recalled Bruce Gibson, a six-term Democratic representative from Cleburne who was later chief of staff to Lieutenant Governor David Dewhurst. “Some guys shaped their whole sessions to try to get on it.”

Those were the members who hoped to impress Burka. For legislators prone to wind up in his crosshairs, he was something else entirely, and other longtime observers referred to Burka’s effect on incompetents as a disinfectant, a yellow line not to be crossed. One said ineffective members needed to wear welding gloves when they tried to handle Burka. “When Paul walked on the floor, members sat up straighter,” recalled former House Speaker Joe Straus. “They’d ask questions that were a lot more intelligent than usual. It was like having the principal walk in.”

And if, by some misdeed, they found themselves on Burka’s Worst list, the impact was real. While there have always been members who swore that the distinction was a badge of honor, inclusion all but guaranteed an opponent in their next race, never a welcome development. Burka’s analysis was always evenhanded but often brutal—he once described a member as having “the spine of a chocolate éclair.” Three former House members independently relayed the same story of an old colleague whose wife left him because she was so embarrassed that he’d been deemed one of the Ten Worst legislators. One Texas Monthly staffer recalled a conversation overheard at an Austin eatery shortly after he joined the magazine in 1977. One of his neighboring diners had just been named to the Worst list. “The thing that really hurts,” said the legislator, “is that when I went back to Dallas this past weekend, my mom had taken my campaign sticker off her car.”

“The first time I met Burka, I asked him what it felt like to be an assassin,” said Cliff Johnson, who served two sessions in the House in the late eighties, before becoming senior adviser for Governors Bush and Perry. “And he replied, ‘I’m not an assassin; I’m a recorder of suicides.’”

Still, the respect paid Burka, be it affectionate or begrudging, reached to the highest levels of governance. “Paul was a thorough and knowledgeable journalist,” said George W. Bush in a written statement forwarded by his office. “He understood state government as well as any Texas reporter, and his voice will be missed.”

I grew up in Austin in the seventies and eighties, well aware that Paul Burka was someone who mattered. My family subscribed to Texas Monthly, and while I was years from being concerned by things like legislative efficacy, I was also accustomed to hearing dinner-table discussions about Burka’s “State Secrets” column—essentially a monthly one-sheet of Capitol scuttlebutt that ran on the magazine’s last page. In the view of my dad, a liberal Episcopal priest, Burka leaned to the right; for my mom, later to become a Fox News devotee, Burka was way too left.

Then, during my junior year in high school in 1983, I somehow wound up at a weekend lecture on state government at the University of Texas law school that was delivered by Burka, a notable nonpracticing alum. It was the first time I ever saw him. He was a large man but not remotely imposing, with a kind face, a soft mustache and mussed hair, and a humility in his eyes that camouflaged a fierce intellect. For an hour he spoke off the cuff, no notes, but in full paragraphs with strong punchlines. When he explained the state Senate’s two-thirds rule, the parliamentary standard that required at least twenty-one of the chamber’s thirty-one members to sign off on a bill before it could reach the floor, I’ll confess to being more informed than enthralled. When he recounted the unfortunate tale of Mike Martin—a former House member who once claimed to have been shot in the arm by devil worshippers, only to admit soon thereafter that he’d had his cousin do it as an ill-considered ruse to boost his reelection efforts—I and everyone else in the room hung on every word.

From then on, I sought out Burka’s byline, poring over iconic cover stories, such as his two-part, National Magazine Award–winning takedown of South Texas bidnessman Clinton Manges (“The Man in the Black Hat,” June and July 1984) and his valentine to Chevy Suburbans (“The National Car of Texas,” August 1986). In college, I actually got to watch him in action when I worked as an errand boy on the House floor for the sergeant at arms’s office during the 1989 session. I noticed that when Burka entered the chamber, the sea didn’t part so much as swallow him whole. Every member wanted his ear. From there, I retraced his footsteps to UT law. I wasn’t sure if I wanted to be a lawyer or a writer, but Burka was the example that proved law school was the right path for either. Then finally, after two-and-a-half unhappy years litigating, I decided that rather than follow Burka’s lead, I wanted to learn from him directly.

In late 1996, I applied to be his intern during the legislative session starting that January. He liked my résumé and references—one of whom was a former Best and Worst Legislators intern who went on to a Rhodes Scholarship—and he gave me the job. (Apparently, if you were a licensed attorney or on your way to Oxford, you made Burka’s cut—for what was an unpaid position at the time, by the way.) That was when I started learning what made Burka so great.

My first lesson that session was on cynicism—or rather, Burka’s utter lack of it. Just before session started, I’d asked another old Capitol reporter, a friend of a friend, for advice on covering politics. He grumpily instructed me to stay away from the Lege and journalism altogether. His exact quote was, “You sound depressed. Isn’t your daddy a clergyman? Surely, he knows someone you could talk to.” Burka, on the other hand, wasn’t skeptical at all. Whether it was in spite of Mike Martin and the varied éclairs or, more likely, because of them, Burka absolutely loved covering the Lege, with no concept of how anyone wouldn’t. His only question was would I like to help him cover the House.

The House, I would learn, was Burka’s domain. Wolens, a Dallas litigator and one of the members Burka most respected, was in his ninth session that year and chair of the powerful House State Affairs Committee. “Paul loved the House,” Wolens said last week, before continuing with the kind of line that made Burka love him as well. “The French philosopher Rousseau once said, ‘The good man is the athlete who delights in fighting naked.’ That’s the House. Members are unbridled in their remarks, aggressive in expressing themselves and their passions. It’s a food fight.” That fact stood the House in diametrical opposition to the Senate, where that two-thirds rule Burka had lectured on guaranteed that only winning bills would make it to the floor. In the House, even bills with huge support were subject to contentious floor amendments and points of order that could kill them instantly.

“The Senate was Kabuki theater,” explained Gibson, another Burka favorite, who was executive assistant to Lieutenant Governor Bob Bullock that session. “It was always the same people giving the same speeches, complimenting their staff, the committee members, and the good people back home. The senators all wore expensive business suits; House members wore bad, polyester blazers and jeans and cowboy boots. We used to look out on the floor and joke about how many polyesters had been killed to dress the membership.”

That was the scene Burka would explain from his favorite late-in-the-day vantage point, the upstairs House gallery, which he liked to call “the owner’s box.” He’d survey the floor, noting who was huddling with whom, which Republicans were twisting the arms of which Democrats, and who looked like they were about to throw punches. To mix the metaphor a little, but keep it to Burka’s beloved baseball, it was like sitting next to Vin Scully at a Dodgers game. “That’s Charlie Finnell,” he’d point and remark. “He’s not going to do anything. He’s furniture.” Or, “That guy holding the big binder is Wolens. He’s the best debater in the House. Anytime he gets near the back mic, especially if he has that binder, listen.”

The overarching value that emerged from his commentary was the primacy of process over outcome. In a twist of the old trope, Burka believed that the best way to ensure that the sausage was good was to detail the methods and motivation of the legislators making it. “He wanted to see a clear vision that could be implemented and skillful navigation of the process,” said Gibson. “He did have moral judgment, but it wasn’t that you be conservative or liberal. It was that you be respectful.”

Burka applied his philosophy to great effect that session, in which two major subplots emerged. The first came from Governor Bush’s office. Burka was a Bush fan; he admired the strong relationship the governor, a Republican, had forged with the Democrats leading the two chambers, Bullock and House Speaker Pete Laney. Bush was a budding national figure with tremendous political capital, and he charged the Legislature with tipping a sacred cow: he told them to retool school financing, asking for massive cuts to its historical source, property taxes, that would be offset by new and higher corporate taxes. Since tax bills must originate in the House, Laney created a special committee to get the job done. The committee, led by Representative Paul Sadler, comprised the brightest minds in the House; privately, Burka called them an all-star team. After months of contentious hearings with business leaders, Sadler presented a bill that won in the House. But through that period, the business lobby that opposed the effort had worked hard on the Senate. Sadler’s bill was dead on arrival.

The other subplot was the unexpected emergence of an extreme right wing of the growing Republican caucus. Early in the session, more moderate legislators deemed them “Shiite Republicans,” a term Burka adopted at the time but would presumably eschew now. Throughout the session, they fought bitterly in back rooms, in committee hearings, and on the House floor, culminating in a historically disastrous night just one week before the final stroke of the session’s clock, sine die. With the skies darkening on Memorial Day Monday, hard-core conservative Arlene Wohlgemuth, a second-term member from Burleson, took to the back mic. Infuriated by delays to a bill requiring parental notification before teenagers could receive abortions, she called a point of order that killed the rest of the calendar outright. All told, 52 bills died that night, 38 of them sponsored by her fellow Republicans, including a charter-schools bill pushed by Governor Bush. The House chamber, almost never a quiet place, looked suddenly like a pro-wrestling cage match.

Unsurprisingly, both Sadler and Wohlgemuth made it onto the Best and Worst Legislators list, albeit at opposite ends. Burka’s write-ups read like a mission statement. On Sadler, he wrote, “Every conceivable political interest was represented [on the select committee]—including ego: Seven of the eleven members chaired other committees. Instead of gridlock, Sadler achieved consensus. . . . He got his committee to agree to examine the state’s tax and school-finance systems from the ground up. They exposed every tax exemption and loophole to the light. The committee’s chemistry produced a level of candor, intelligence, and political acuity that ennobled the entire political process.” His description of Wohlgemuth was the flip side of that coin. “She broke the social contract that is the basis of all government: the agreement to give up the right to use brute force in exchange for the benefits of civility and order. That makes her the worst of the worst.”

The next great lesson of that session was taught not by Burka but about him. There was a joke at Texas Monthly in those days that you could tell what week the magazine’s production cycle was in by how mad the edit staff was at Burka. If an F-bomb preceded his name, the magazine was in week four—deadline week—and his story had yet to come in. The office shorthand for the phenomenon was death, taxes, and Burka; his procrastination was that reliable.

This was especially true of the Best and Worst Legislators lists. Legislative sessions always end just after the first of June, leaving barely two weeks before the July issue’s deadline. And as was evidenced by Wohlgemuth’s tantrum, the final word on a session could not be penned until the lawmaking was over, which left an unreasonably short window to write, edit, copy-edit, and fact-check a 10,000-word-plus beast of a story filled with dozens of moving parts, many of them controversial.

Though my internship ended with the final gavel of sine die, I wanted in on that chaos. As the write-ups trickled in, first from Burka’s trusted coauthor on the Senate, Patricia Kilday Hart, and then finally from Burka himself, I worked with the fact department to ensure accuracy. Luckily, Hart and Burka were first-rate reporters. Still, everything had to be independently verified, and in those ancient, pre-internet days there was no indexed, online archive of floor proceedings or committee meetings to speed up the process. So I spent my time in the legislative reference library at the Capitol, fast-forwarding through cassette tapes of hearing and floor testimony to find quoted bits of oratory to make sure the i’s were all dotted and t‘s all crossed. It was an exhilarating experience—especially once the story came out and the Texas political world erupted.

Some six weeks later, there was an opening in the fact department. At Burka’s insistence, I was the only candidate considered, which is how I got my career. I worked as a fact-checker for the next five years, grousing about Burka as much as anyone but also volunteering to take every one of his stories I could. Reverse-engineering a Burka piece—be it on politics, baseball, Aggies, Dennis Rodman, whatever—was a better way to learn how to do good journalism than any college course ever offered.

After he took over our monthly Behind the Lines op-ed column in 2000, it typically meant another mad dash at press time. With a drop-dead, gotta-send-it-to-the-printer deadline on Thursday morning, Burka’s drafts invariably came in early in the evening on Wednesday. They typically concerned some current hot-button political issue or scandal, and I couldn’t start making verification calls until nine or ten o’clock—or later. Each month I’d reach out to the kinds of people quoted above. Just as they all called back to talk about Burka after he died, they all took those eleventh-hour, Wednesday night calls. Sure, they necessarily had an interest in the subject matter. But I could tell from their tones that they also had absolute respect and even affection for Burka. Equally important, they knew the calls would be quick. Burka just didn’t make mistakes.

The last Best and Worst Legislators list I worked on before becoming a staff writer was in 2001, and it was a typically pointed Burka effort. He noted the rare week off given to the Lege so that members celebrating Bush’s rise to the White House could attend the inaugural festivities in Washington, D.C., then lamented the identity crisis suffered back home now that the bipartisan leader was gone. It was exactly the kind of analysis Burka always delivered.

There was one huge surprise though. Arlene Wohlgemuth, now an erstwhile nemesis of liberals, moderates, and even some conservatives, had followed her Memorial Day Massacre with a second appearance on the Worst list in 1999. But in 2001, she wound up among the Best. He crafted his write-up as a “Dear Arlene” open letter, leading off with an apology if his stamp of approval would hurt her street cred with what was now called the Black Helicopter Caucus. He went on to describe her session in that familiar informed, prescient voice. “By advocating things that government ought to do—including protect the rights of mobile homeowners, come to the rescue of financially troubled nursing homes, and require insurers to cover birth control prescriptions for women, as they do Viagra for men—you paved the way for the time, not far distant, when Republicans will take up the burden of running the House. Best of all, you didn’t try to kill the important bill that expanded Medicaid services, even though you warned that it could sink the state budget in future years, but instead negotiated a compromise to contain costs and supported it in floor debate. That’s leadership.”

He had applied the same standard as always, but where Wohlgemuth had previously offended it, this session she’d exceeded it. Burka put his faith in legislators who followed their hearts, but firmly believed they had to respect what was in other members’ hearts as well. To his mind, that was the only way to make Texas better, and making Texas better was the sole purpose of the Lege.

It was Burka’s primary purpose as well, and one that he pulled off. When I asked former Speaker Pete Laney to sum up Burka’s career, he offered up a line that, in terms of its economy, simplicity, and lack of even a hint at his own policy druthers, was all but Burka-esque: “He left the state better than he found it.”

- More About:

- Texas History

- Texas Legislature

- Paul Burka