This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The first and last person to claim sole ownership of Texas was Charles V, who ruled Spain from 1516 to 1556, and even he might have changed his mind if he had ever gotten closer than six thousand miles. For the first three hundred years after its discovery the expanse of land now called Texas was pretty much available for the asking. Other regions had more minerals, more fresh water, better weather, deeper ports, prettier scenery. All Texas had was land—millions of acres, mostly drab and dry, with plenty of Plains Indians to guard it. But now that same land represents one of the best investments in the world, and on the roster of Texas’ owners are international moneymen ranging from Venezuelan ranchers to the wealthiest royal families of the Middle East. Most of the largest owners, though, don’t answer to any nationality but “Texan”; they are descendants of the nineteenth-century pioneers who took a flyer on the vast emptiness south of the Red River. A single acre of this state, which sold for a nickel more than 150 years ago, today has a median value of $600.

A lot happened between those two prices. What made Texas special in the early nineteenth century was that it had more available cheap land than any other place in the world. Monotonous land, perhaps, but it was for sale. A single Texan could accumulate a million acres and more by buying up railroad lands, failed ranches, school lands, and old Spanish land grants and by asking all his employees and friends and relatives to apply for homesteads. In a pinch, he would send the hands out to fence public rangeland, tending to the deeds later.

You could call it greed, but it wasn’t exactly that. It was contagion. With the invention of barbed wire and the closing of Western frontiers by about 1875, the attention of the world turned to the young state of Texas, where 60 million acres remained to be given away—nearly two Alabamas. Britishers and Belgians and Yankees arrived by the Pullman-load to claim the open range, oblivious of traditional range rights. Land fever had struck, and the Legislature rejoiced. “The sooner the public domain is gone, the better,” said one state senator.

The Legislature got what it wanted. Land is nothing without people to settle and develop it, and if cheap land was what it took to bring them, that was fine. By 1898 the Texas Supreme Court had to call a halt to the rush; the Legislature had signed away 146 million acres.

Just what did the Legislature get for all this land? It got 10 million acres’ worth of soldiers; it got cash for the schools; it got canals, steamboats, roads, wells, and 32 million acres’ worth of railroads. For 3 million acres, it got a state capitol nearly as high as the one in Washington. The University of Texas, which is now second only to Harvard in the size of its permanent endowment, owes that position to oil-soaked West Texas land deeded to it in the last century. Most of all, though, the promise of land unlimited brought settlers, so many that even the unflinching Comanches and Kiowas had to fall back.

Land has been the source of all the great family fortunes in Texas—whether the money came from cotton, cattle, or oil—but its power is wielded in silence. The Klebergs of the King Ranch are notoriously tight-lipped about their South Texas ranching empire, one of the world’s largest. The R. L. White family, owner of the largest ranch in Bexar County, is virtually unknown in San Antonio real estate circles. And few owners keep a lower profile than former governor Dolph Briscoe. These remnants of a once-flamboyant landed gentry represent only a tiny fraction of the state’s owners. Most of Texas—about 80 per cent of its 169 million acres—is now checkerboarded with small farms and ranches that average less than 1000 acres. Generations of inheritance taxes, squabbles over wills, and creeping urban development have sapped the strength of most old ranching empires, drawing the land away. But Texas is still one of the few places in the world where five families can own an entire mountain range (the Sierra Diablo) and one man can own a peak like Mount Livermore, the state’s fourth highest. We may even see multimillion-acre land empires rise again, but the owners will be the new strongmen of our society—corporations, trusts, and untaxed religions.

Who owns Texas today? To find out, I spent two months on the road, tracking land ownership (which I defined as fee title to the surface of dry land) through county records, real estate sources, and the heirs to the state’s largest ranches. I found the top fifteen owners of rural land and the largest owners of that precious property in and around Dallas, Fort Worth, Houston, and San Antonio. The largest holders of rural lands fall into three groups—government, timber companies, and a few ranching families that have held their property into the fourth or fifth generation. Of these, the first two are more or less steadily expanding their holdings, while the third is barely holding its own. There is something sad in this, the passing of the big-ranch era. The individual owners, heirs of self-made men, feel threatened by more than the familiar risks of drouth, disease, and poor prices for cattle. They fear government interference with their property—or their “country,” as it is known in West Texas —and that interference is not limited to taxation. It goes to the heart of the question of how the land is used. It springs from a growing public opinion that there is no resource more limited than land, that we are all trustees of the good and fragile earth.

It will be a long time before the last independent landholders relinquish control over their inheritance, though. In the vast unpeopled prairies of West Texas, ranchers with rifles still chase off General Land Office employees seeking to inspect land leased from the state, and they still build their property-line fences straight up the sides of cliffs so as not to give up a single acre out of a quarter-million. All things considered, I can’t think of a more territorial people.

Ranchlands: Railroading Kings and Cowboys

| Owners | Acres |

| Texas Pacific Land Trust – West Texas | 1,274,000 |

| King Ranch – South Texas | 825,000 |

| Waggoner estate – Central Texas | 500,000 |

| W. B. Blakemore II & family – West Texas | 455,000 |

| Burnett Ranches – Central Texas | 451,000 |

| Kenedy Ranch – South Texas | 450,000 |

| Dolph Briscoe & family – Southwest Texas | 414,000 |

One of the more curious remnants of the Texas Legislature’s great land giveaways, the Texas Pacific Land Trust, was formed in 1888 by the scheming financiers from the East who held the state’s railroads in thrall. Texas was so eager to get railroads—any railroads, going anywhere —that the Legislature offered sixteen square miles of free land for every mile of track constructed. Result: Thomas Scott, representing the Andrew Carnegie interests, and Jay Gould, the Mephistopheles of Wall Street, took control of the Texas & Pacific and built more than a thousand miles of rickety track out to El Paso. That much track entitled the railroad to an awesome 10 million acres of land. The route went unused, and to no one’s great surprise, the railroad went bankrupt in 1887. During the 1888 reorganization the Texas Pacific Land Trust was formed in a thinly disguised legal maneuver around the state law requiring railroads to sell off their land grants within twelve years. The trust started with 3.4 million acres (the railroad had been entitled to 7 million more but couldn’t wrench it out of the Legislature), and almost a century later it is still the largest private landowner in Texas. And at the rate the trust is liquidating its holdings—15,000 acres per year—it will be around for another 85 years to come.

The trust is administered by an agent named James McCaul, who represents some 3500 shareholders out of his Dallas office. The three men who control the land, as Texas Pacific trustees, are Maurice Meyer, Jr., an investor who lives in Elberon, New Jersey; George Fraser III, a consulting geologist in Abilene; and George A. Wilson, now the honorary chairman of Lone Star Steel in Dallas. Most of the land is in West Texas, and practically all of it is leased to cattlemen for grazing.

The King Ranch, on the other hand, is a family corporation that has maintained an unbroken chain of Texan ownership and management ever since 1853, the year a steamboat captain named Richard King purchased 15,500 acres southwest of Corpus Christi. Today King Ranch, Inc., holds title to 825,000 acres in four ranches between Corpus Christi and Brownsville. The shareholders number forty or so descendants of King’s daughter Alice and her husband, Robert Kleberg.

The Waggoner Ranch, also known as the Three D (for its distinctive reverse triple-D brand), is less famous than the King Ranch but just as old and almost as big. Founded in 1851 by a genuine cowboy named Daniel Waggoner, it once ranged over more than a million acres in northern Central Texas, and today it remains the largest single piece of privately owned land in the state. A half-million-acre spread south of Vernon, the ranch was diminished by estate taxes and by division among Waggoner’s three grandchildren in 1909, but it was rescued by oil production beginning in 1911. All the property was merged into the Waggoner estate in 1923, and after the death of Waggoner’s son, W. T. Waggoner, in 1934, the management of the estate was left to a trustee and board of directors. Today Electra Waggoner Biggs, her two daughters, and Bucky Wharton—who are all descendants of the founder—are beneficiaries of the trust.

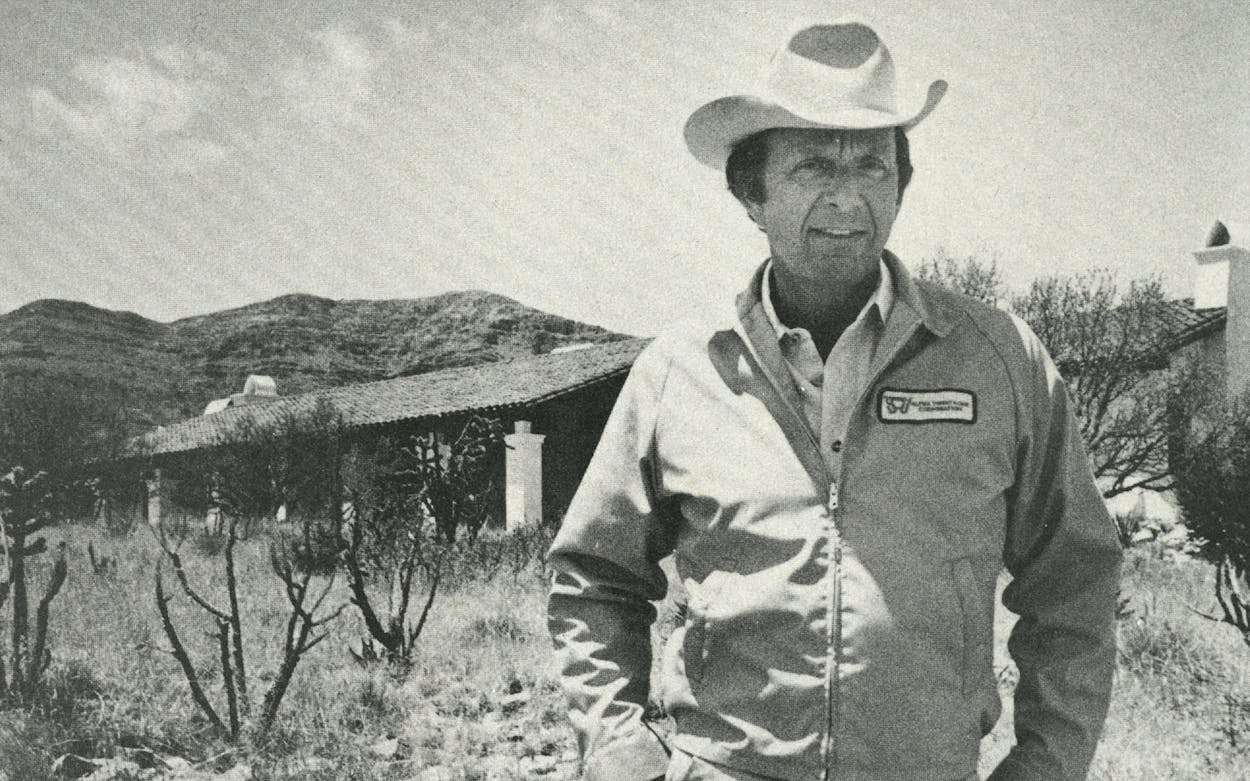

The third largest ranching group is the family of William B. Blakemore II, a laconic West Texas businessman who operates out of a plush Midland office under the corporate name Alpha-21. Like many of the older ranching families, Blakemore and his five children are discreet about their holdings, but my research turned up more than 455,000 acres in five West Texas counties, most of it listed in the names of family members or under a company called Longfellow Corporation.

In the early part of this century, Houston lumberman J. M. West began acquiring ranchland in the rugged West Texas wilderness, ultimately accumulating more than 100,000 acres. Later he struck oil on enough of them to become a millionaire. The land passed to his son, Jim “Silver Dollar” West, who had a daughter named Marian, and therein hangs a Blakemore family legend.

The young heiress, a delicate woman who spent most of her life enduring various illnesses, married William B. Blakemore II. Blakemore was totally devoted to her, so much so that he built for her a fabulous house, La Primavera—which covers a half-acre of land in the Glass Mountains. When she died, he buried her on the most beautiful of all the family ranches, the Iron Mountain, just north of Marathon in Brewster County. The chapel near her grave is visible from La Primavera.

Blakemore is also notable for being one of the few large ranchers who are still actively adding to their holdings. Since the preparation of the 1979 tax rolls, the family has acquired a 14,700-acre ranch near Marfa.

In many ways the four ranches of the Burnett estate, spread across four counties at the base of the Panhandle, demonstrate that ranching empires can survive a century of wills and property taxes. The 6666 Ranch was founded by a cattle driver named Samuel Burk Burnett in 1875, and his legacy has survived for two reasons: lots of oil and very few children. When Burnett died in 1922, the oil revenues from his four Texas ranches and others in Oklahoma and New Mexico were sufficient to preserve the empire intact for his family after all estate taxes were paid. He bypassed his only son, Tom, to leave most of the ranch in the hands of his only granddaughter, Anne Valliant Burnett (the late Mrs. Charles Tandy of Fort Worth), who passed it along to her only daughter, born of her second of four marriages, Anne Windfohr Phillips. Most of the original empire is still in her hands, and it will presumably be inherited by her only daughter, Windi Phillips. Meanwhile, the oil wells are still pumping away and paying off the inheritance taxes.

Slightly smaller than the Burnett holdings is the Kenedy Ranch, in the midst of the four divisions of the King Ranch in far South Texas. While the ownership of the King Ranch is shared among dozens of relatives, the Kenedy Ranch is still concentrated. Half is owned by the widow of John J. Kenedy, Jr., the founder’s grandson. The other half, the estate of Sarita K. East, his granddaughter, has been tied up in court since 1961, when she left it to a family foundation, choosing as executor a Trappist monk.

Finally, we have former governor Dolph Briscoe, whose family corporations hold at least 414,000 acres in nine southwestern counties. Despite the insistent rumors that Briscoe owns more than a million acres, most of his cattle operations are on leased land. Briscoe is adding to his holdings, though, usually by buying up virtually worthless mesquite-choked range and spending thousands of dollars for brush clearing.

East Texas Timberlands: Money Growing on Trees

| Owners | Acres |

| Temple-EasTex, Inc. | 1,067,000 |

| Kirby Forest Industries | 585,000 |

| St. Regis Paper Company | 570,000 |

| Champion International | 490,000 |

| International Paper Company | 429,000 |

Just as the flatlands of West Texas fostered the world’s greatest ranches, the Piney Woods of East Texas was once considered one of the nation’s premier timber regions. The harvesting of timber has actually been on the decline since 1907, the year Texas ranked third behind Washington and Louisiana in lumber production. The timber industry turned another corner in 1978, when for the first time since the early 1900s the Texas pine harvest exceeded the year’s growth.

The attractiveness of the East Texas pine persuaded Time, Inc., the New York publishing conglomerate, to become the second largest private landowner in Texas in 1973, the year it purchased Temple Industries from Arthur Temple of Diboll in exchange for a huge block of Time, Inc., stock. The resulting subsidiary, Temple-EasTex, now owns more than a million acres in 26 East Texas counties—or 30 per cent of all commercial forest in Texas.

The other major corporate owners are the Santa Fe Railroad, which owns Kirby Forest Industries of Houston, and St. Regis Paper, which recently bought up Southland Mills and all its landholdings.

Foreign-owned Lands: Petty Sheikdoms

Every few months the xenophobes come out of their caves to declaim against the coming onslaught of Arabs and other rich outlanders who are trying to seize control of Texas farmland and mortgage us all to OPEC. As a matter of fact, foreigners owned much more of Texas a hundred years ago than they do today. The latest figures released by the U.S. Department of Agriculture show the percentage of foreign ownership at a minuscule 0.4 per cent.

Nevertheless, there are good business reasons for Arabs and Europeans to invest in Texas real estate, especially whenever the dollar is declining. In fact, the state encourages foreign investment by offering tax advantages on agricultural land that are available in few other places in the world. Thanks to the passage of the federal Agricultural Foreign Investment Disclosure Act of 1978, which requires nonresident aliens to reveal their holdings, we have more or less accurate figures. The latest tabulations, released in April, show foreign ownership at 527,719 rural acres, indicating a rate of purchase that should turn the state over to foreigners sometime around the dawn of the 26th century.

Mexicans and Europeans account for the bulk of the acreage, and Arabs appear hardly at all. (That doesn’t necessarily mean much, since the Arabs are noted for channeling funds through Canadian corporations and Caribbean tax havens.) Most of the foreign money is concentrated in the state’s most fertile area, the Rio Grande Valley.

Hidalgo County, which produced more crop value than any other county in Texas last year, has a rate of foreign ownership twenty times the state average. About one ninth of the county is owned overseas or in Mexico. In the country around McAllen, you can meet people from all over the world but especially from West Germany, Hong Kong, Namibia, Liechtenstein, Canada, and Austria. Many of the companies listed on the tax rolls have addresses in the Netherlands Antilles or the Bahamas, which are tax havens, and almost all of them are absentee owners.

The next largest concentration of foreign ownership occurs several hundred miles away in the Trans-Pecos region. Out in Hudspeth County (which is twice the size of Delaware but has a population of only 3000) and three other West Texas counties, a pair of Greek shipping magnates named Vardis and Theodore Vardinoyannis recently purchased 54,000 acres of ranchland. What they plan to do with it is anybody’s guess, since they have no offices in the United States and manage the land through a Panamanian corporation called Lado Compania Naviera. The rumor is that the Vardinoyannis brothers are currently looking at another spread of 102,000 acres in Hudspeth County that includes Sierra Blanca Peak, among other things. The only individual owner in a league with them is Franz Josef II, a gentleman farmer who is also prince of Liechtenstein, and whose Texas holdings are larger than the nation he rules.

Most of the other big foreign owners hold urban acreage. Canadians, for example, own 10,700 acres in the Dallas–Fort Worth area. Cadillac Fairview of Toronto owns half of the Houston Center project. Carma Development of Canada has 1400 acres in Harris County. Houston’s foreign-owned buildings include Pennzoil Place (Deutsche Bank AG), portions of both Shell plazas (Grundbesitzverwaltungsgesellschaft MBH Company), and the Meridien Hotel (Air France).

Public Lands: Selling Uncle Sam Short

| Owners | Acres |

| State of Texas | 6,400,000 |

| U.S.A. | 3,293,000 |

| University of Texas System | 2,100,000 |

The state government, never known to underestimate what it owns, actually claims about 19.5 million acres, but 5 million are underwater and about 8.1 million involve mineral rights only. Those 6.4 million dry-land acres are a far cry from the 216 million acres of land claimed on March 2, 1836, when Texas declared independence. About two thirds of the 6.4 million acres are temporary holdings of the Veterans Land Board program, whereby the state purchases small tracts for retired soldiers and holds the land for them until they’ve made their last payments. The largest land empire within state government is the Department of Highways and Public Transportation, which holds 1,039,000 acres in rights-of-way. (Highway rights-of-way were not considered in totaling urban figures, as there is no reliable way to separate the ownership between the governments.)

Unlike most of the Western states, which had to fork over their public lands as the price of statehood, Texas kept its public domain and made the feds pay for every last square foot of their acquisitions. Consequently, while the U.S. owns 90 per cent of Alaska and a majority of four other Western states, it has a mere 2 per cent of Texas, most of which is operated by the National Park Service, the Forest Service, and the Army Corps of Engineers.

Finally, the University of Texas System owns both surface and mineral rights to parts of seventeen West Texas counties, a region so hot, dry, and dusty that it was an embarrassment to the state—and a symbol of our neglect of higher education—for several decades. But the Legislature’s folly was turned into wisdom on May 28, 1923, the day Santa Rita No. 1 blew in on university land in Reagan County, bringing in the first of more than a billion dollars in oil and gas royalties, and making UT the richest state university system in the nation. Overseeing the grazing leases is the province of UT land manager Billy Carr, whose office is in Midland.

Harris County: A Developing Tiger

| Owners | Acres |

| Exxon Corporation & subsidiaries | 29,300 |

| U.S.A. | 28,100 |

| City of Houston | 18,000 |

| John Warren estate | 7,968 |

| L. M. Josey & family | 7,800 |

| Champion International | 7,100 |

| Harris County | 6,800 |

| H. J. Longenbaugh estate | 6,440 |

| Roy Seaberg & family | 6,170 |

Not too surprisingly, since it is now the nation’s largest corporation, Exxon owns 3 per cent of Harris County, the world’s energy capital. It is surprising, though, to learn that aside from the land it uses for tank farms and its Baytown refinery complex, much of the Exxon land is being developed strictly as real estate. The tiger, as it were, is going from your tank to your back yard. Friendswood Development Company, an Exxon subsidiary, is Houston’s largest developer, with 15,000 acres of land (much of it jointly owned with the King Ranch). Exxon’s real estate ventures include the exclusive enclaves of Kingwood, Copperfield, and Woodlake, as well as a 2000-acre industrial park just southwest of the city.

Aside from the federal government, which owns the Johnson Space Center in Clear Lake City and the Addicks Barker flood-control reservoirs, and the City of Houston, with its parks and Navigation District, the third largest public landowner is Harris County, with 58 parks and a number of landfills.

The rest of the large landholders in Harris County are part of a vanishing breed—ranchers and farmers who are far enough away from the urban sprawl to resist the temptation to sell. L. M. Josey, in the northwest, the H. J. Longenbaugh and John Warren estates, also in the northwest, and the Roy Seaberg family in the northeast hold land an average of twenty miles from the central business district. That may not be far enough, though; Friendswood’s Copperfield development is opening up just three miles from the Josey Ranch.

Smaller in quantity but greater in value is the land held by the estate of legendary Houston developer R. E. “Bob” Smith. Smith started buying dozens of parcels of prime land after World War II and at one time owned about 11,000 acres; his estate presently holds about a third of that.

Near the Seaberg farms, northeast of Houston, are the lands of Champion International, a paper company that is converting most of its acreage into real estate subdivisions.

Inside the central business district itself, which has the highest land values in the state, the owners of the most land are Texas Eastern Transmission Corporation (a giant utility) and Cadillac Fairview of Canada. The two companies are co-owners of the 47-acre Houston Center project, 33 blocks of downtown real estate that were put together with a secrecy usually reserved for international espionage. George R. Brown of Brown & Root fame, who is handling the project for Texas Eastern, plans both office and residential development, all of it to be connected by above-the-street walkways.

The other major owners of prime land are Gerald Hines Interests—developers of 360 floors of Houston office and retail space—and Kenneth Schnitzer’s Century Development. Schnitzer is currently completing more than $600 million worth of real estate projects, including Greenway Plaza, Summit Tower, and Allen Center, with its new 50-story Capital National Bank Plaza.

Dallas and Tarrant Counties: The Speculator’s Paradise

| Owners | Acres |

| City of Dallas | 33,900 |

| City of Fort Worth | 15,200 |

| U.S.A. | 11,800 |

| Las Colinas Corporation | 10,000 |

| H. L. Hunt family | 8,000–9,000 |

Any attempt to name the largest individual landowners in Dallas or Tarrant counties is fraught with peril, since the market changes so fast that a map more than six months old is suspect. The leaders are easy: Dallas, with its extensive and enviable park system, owns much more land than most cities its size, and more than twice as much as its sibling rival, Fort Worth, which shares ownership of the Dallas–Fort Worth Regional Airport. But the largest private owner is in neither Dallas nor Fort Worth but between the two in Irving, on a 10,000-acre spread just east of DFW. In fact, the Las Colinas Corporation, with all its partners and joint venturers, holds one of the single largest blocks of undeveloped land to be found in any metropolitan area in the country. (A 2200-acre ranch was just acquired in February.) Once developed, Las Colinas will be a futuristic planned community that will include everything from houses to condominiums to offices to light industry, and many of the buildings will be connected by a Venice-like system of canals. Ben H. Carpenter and Dan Williams of Southland Financial Corporation (not the Seven-Eleven Southland) are the creators of Las Colinas, which got under way about 1973.

After Las Colinas in size are the various speculative properties of the inscrutable Hunt brothers. Some of the acreage is owned by the silver bugs, Nelson Bunker and William Herbert, and some is owned by Ray Hunt through his Woodbine Development Corporation. Woodbine is the outfit that developed the Reunion complex—hotel, tower, restaurants, and sports arena—on the western edge of downtown, and that is presently developing prime land near the Quorum retail area in the northwest. The family is also speculating on high-rise office buildings in both Dallas and Fort Worth.

The largest developer of top-value land in the Metroplex is undoubtedly Trammell Crow, who is first and foremost a builder and lessor of warehouse space. Among his glamour projects are the Dallas Market Center (including the Apparel Mart), the posh Loew’s Anatole Hotel, Caruth Plaza, 2001 Bryan Tower, the new Diamond Shamrock Building, and 23 acres of the Quorum (office and retail).

Bexar County: A Mighty Fortress

| Owners | Acres |

| U.S.A. | 46,000 |

| Ellison Industries | 12,000–14,000 |

| R. L. White family | 9,200 |

| City of San Antonio | 8,600 |

| San Antonio Ranch, Ltd. | 7,900 |

| Mrs. V. H. McNutt | 5,000 |

Thanks to the flat terrain and perennially good flying weather, the federal government has long looked to San Antonio as one of its favorite sites for military flight training. Hence the city’s six major military installations make Uncle Sam its most important employer and its largest landholder by far.

The largest private landowner, Ellison Industries, has acreage on all sides of the city but principally in the north and northwest, where its subsidiary, Ray Ellison Homes, has been busily building residences for the past several years. Similarly, the San Antonio Ranch, Ltd., is no longer a ranch at all but a real estate development just getting started, with about 500 acres of an 8400-acre tract developed and sold.

The other two private owners are both ranchers. The heirs of R. L. White hold 9200 acres in the northwestern part of the county but are so secretive that not even the local chamber of commerce knows much about them. The Whites also own Uvalde Mines, a rock asphalt operation based in San Antonio. As gregarious and outgoing as the Whites are reserved, Mrs. V. H. McNutt is the owner and sole proprietor of the 10,000-acre Gallagher Ranch (only half of it is in Bexar County), which has survived intact from the 1850s. Mrs. McNutt, now a grandmother, bought the property 53 years ago and continues to run about 260 head of cattle with the help of her four ranch hands.

San Antonio has no counterpart to Houston’s Gerald Hines or Dallas’s Trammell Crow, but the largest owners of prime downtown real estate are National Bank of Commerce, Frost Bank, and Alamo National Bank, which is both restoring old space and building new.

Vacancies: Fortunes for the Asking

In the hustle and bustle of distributing all that land, the state made some mistakes. Some persist to this day; the most important are called vacancies. Ray Wisdom, retired director of surveying for the General Land Office, defines a vacancy as “a piece of land surrounded by oil wells.”

Many large land grants came in the form of certificates for a given number of acres to be selected from a certain location. As certificate holders chose their property, county maps filled with scattered blocks of surveyed land. As these blocks began to nudge up against one another, surveyors uncertain of their ground often left strips of vacant land in between, figuring that there was lots to go around and, in any case, it was better than causing feuds decades later between landowners whose properties overlapped. This state of affairs suited everyone until oil was discovered. By 1920 people called vacancy hunters were scouring the land records to find such unappropriated strips—in an oil field if they were lucky. Then they would hurry to file a claim for purchase of the land from the state at a bargain price.

In 1927 Fred Turner, Jr., found one such strip in the middle of the fabulous Yates Field in eastern Pecos County. He had to spend six years in court to get it, but that land made his fortune. To date, his 560 acres has produced over 22 million barrels of oil, and it won’t run dry until the middle of the next century. Less successful was Walter C. Atchley, who spent nine years trying to claim an immense 12,000-acre vacancy lying across the oil fields of San Patricio County. At stake was $1 billion in oil revenues. He lost in every court and finally conceded defeat in 1974 after failing to pin a conflict-of-interest charge on the Texas Supreme Court.

There could be other court fights in the future. “I’m sure there are vacancies left, yes,” says John Foshee, legal counsel for the General Land Office. “There’s too much land in Texas for there not to be.” The vacancy statutes are less generous now than in the days of Fred Yates, but oil and gas royalties are still available to people who find one in the right place.

How Big Is Texas?

In 1842 the sober gentlemen of the Texas Congress took a vote on how big Texas was. They claimed everything we know as Texas today, plus all of Utah, California, Nevada, Arizona, and New Mexico, plus all or part of eight states in Mexico (about one third of that country), plus large parts of Wyoming, Colorado, and Kansas. Various claim jumpers took most of that away from us, so what we have left today is a mere 801 miles from north to south, 773 east to west.

You might think that after 130 years of statehood we could at least agree on exactly how much area those boundaries enclose. Think again. The United States Department of Commerce, for example, estimates that area at 167,797,952 acres. Meanwhile, the experts over at the General Land Office think Texas is 169,356,000 acres in size. That’s a disagreement of over 1.5 million acres, or about two and half average Texas counties. Four other state and federal agencies report differing figures that fall somewhere between those two extremes. The Bureau of Land Management and the U.S. Department of Agriculture win the award for almost agreeing.

How big is Texas? As big as we want to make it.

- More About:

- Business

- TM Classics

- Longreads