Consider, for a moment, Texas through the eyes of an outsider. On January 13, 2013, just two months after President Barack Obama won reelection, the White House formally declined an online petition signed by more than 125,000 people that would have allowed Texas to secede. The government of Belarus weighed in, expressing its concern that Texas independence was being suppressed. When Obama nominated John Kerry for secretary of state, three senators voted against confirming their colleague from Massachusetts: John Cornyn, the senior senator from Texas; Ted Cruz, the junior senator from Texas; and James Inhofe (nice try, Oklahoma). Meanwhile, state attorney general Greg Abbott took out an ad on the website of the New York Times directed at gun owners in the Empire State: if they were concerned about stricter gun control in the wake of the school shooting in Newtown, Connecticut, they should move to Texas, where they wouldn’t have to worry. A few weeks later, Rick Perry went to California on a hunting trip—job huntin’, that is.

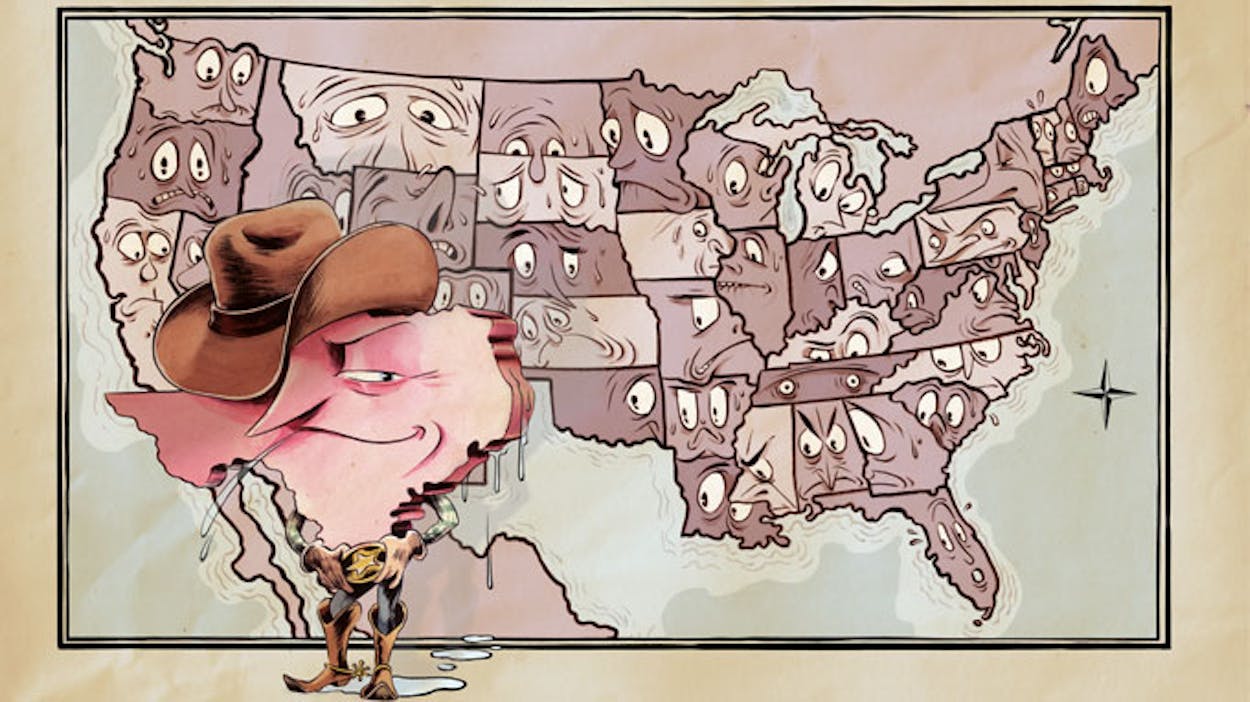

Perhaps, then, it’s no wonder that around the country there has always been a widespread impression that Texas is corrupt, callous, racist, theocratic, ignorant, and belligerent. Even worse, many Americans think Texas is dangerous: all the terrible stuff this state does creeps into the rest of the nation through the underhanded strategies of textbook distribution and national elections.

That notion is mean. It’s wrong. And it’s easy to see how it’s reinforced by stories like the ones mentioned above. On the other hand, those events make the headlines because Americans are wary of Texas in the first place. So this raises the question, Why would people be scared of a state?

The mutual suspicions between Texas and the United States have been around so long that it’s impossible to say when they started. We could go all the way back to the annexation debate of 1836–1845, when the Republic of Texas’s bid to join the Union caused so much consternation in Washington that some historians consider it the proximate cause of the Civil War. Or we could go to the Civil War itself, a conflict in which Texas was on the wrong side of history, morality, and the American Constitution. Clearly the United States had some trouble with Texas even before that November day in Dallas that horrified the world—and that left the nation with a new president, who struggled to redeem his home state’s reputation.

But this isn’t the only state that was part of the Confederacy. It’s not the only state that has been the home to a national tragedy. So if Texas is more controversial than any other state, maybe something else is afoot. Refer yourself to J.R. from Dallas or Rich Texan from The Simpsons (“Without oil, you wouldn’t have four-wheel drive!”). Think of Tex Richman, the villain in the most recent installment of The Muppets, who buys the Muppets’ old theater because he wants to get at the oil underneath. Or consider This Is Texas, part of a sixties-era children’s series by Czech illustrator Miroslav Sasek that includes This Is Paris and This Is New York. “Leonard’s Subway, the only privately owned subway in the world, takes you from the parking lot to Leonard’s Department Store,” Sasek writes. “No charge. It is also the only subway in Texas where passengers might drown in oil.”

The first gusher in Texas was discovered in 1901, at Spindletop. Thirty years later, the state’s oil industry became even bigger with the discovery of gargantuan reservoirs in East Texas. Before oil, Texas didn’t have enough wealth or power to influence the country. After oil, it did. The state could no longer be dismissed as merely eccentric. In other words, Texas became a problem for the rest of the country when Texans started to get rich. Oil created a clutch of super-empowered businessmen—super-empowered economically and politically. Rich Texans weren’t shy about using their newfound wealth to push for favors, and they were successful enough at doing so that the nation started to pay attention. As early as 1933, when Franklin D. Roosevelt was president, national politicians were trying to close the loopholes that were helping this crop of wildcatters become wealthier than seemed reasonable. The politicians didn’t succeed. Over the decades, as the special treatment for the oil industry continued, the nation’s resentment of it, and Texas, only strengthened.

To make matters worse, after the oil industry brought wealth and influence to Texas, its residents started getting ambitious about other things. In 1982 Ronald Reagan signed a bill that briefly made life easier for America’s savings and loan institutions by implementing regulations that were modeled after Texas’s freewheeling rules on the subject. Some years before, the state had loosened up its restrictions by reducing the amount of deposits S&L’s were required to keep on hand and allowing the thrifts to lend money for commercial real estate projects. At the time, financial deregulation seemed to be working. Greater access to capital had given more Texans a chance to hunt for oil. Others focused on real estate development: all those people who were getting into oil would surely want to buy swanky condos and office towers.

What happened after the nation followed suit could probably have been predicted, in retrospect. Interest rates were relatively high in the early eighties, so investors were saving more money than usual. The S&L’s, being flush with cash and having more discretion as a result of Reagan’s new rules, lent more money than usual. When interest rates came back down, however, investors wanted to move their money elsewhere. Hundreds of America’s savings and loans institutions, having lent out most of their deposits, abruptly failed.

In 1989 George H. W. Bush—who had been elected president the previous year after serving as Reagan’s vice president—signed what was, at that point, the largest federal bailout in U.S. history (it was exceeded when his son George W. signed the Troubled Asset Relief Program, in 2008). According to ProPublica, an investigative journalism group, the final tab worked out to about $220 billion. Texas was home to many of the failed institutions and came in for more of the bailout funds than other states. That really rankled the rest of America, because the wealthy Texans who had had the bright idea to deregulate in the first place had spent much of the seventies lolling around on piles of oil money, building skyscrapers and drinking rivers of wine with names they couldn’t pronounce as their fellow citizens in other states shivered through the winters because oil prices were so high that no one wanted to turn up the heat. Adding insult to injury was the fact that Texas got to keep all its new buildings.

The result was a very low point for U.S.-Texas relations. In 1990 Seth Kantor, a reporter for the Austin American-Statesman, summarized the mood in Congress as one of “mouth-foaming distemper over Texas.” He quoted Frank Lautenberg, a Democratic senator from New Jersey: “This massive theft of New Jerseyans’ pocketbooks was not some random bolt of lightning from God. It was largely the result of conscious, calculated decisions made by Texas itself.”

Kantor also pointed to a withering complaint by the Chicago Tribune’s editorial board, who wrote, “The Midwest will get no direct benefit in return for exporting its wealth to the Southwest. In fact, we’ll have to work that much harder to keep our own economies growing. Meantime, our dollars will help keep Texas oilmen in rattleskin boots and fancy cars.”

Yet time has shown that even a groundswell of popular enmity can’t chasten Texas plutocrats. In fact, to judge from their public statements, they actually think people ought to show them more respect. “What I find interesting about the U.S. relative to other countries is in most every other country where we operate, people really like us,” said Rex Tillerson, the CEO of Irving-based ExxonMobil, in an interview with Fortune’s Brian O’Keefe last year. “And they’re really glad we’re there. And governments really like us. And it’s not just ExxonMobil. They admire our industry because of what we can do. They almost are in awe of what we’re able to do. And in this country, you can flip it around 180 degrees. I don’t understand why that is, but it just is.” If he’s really perplexed, of course, it shouldn’t be that hard to find someone who’d be happy to offer him an explanation.

TO FOCUS ON THE EXCESSES of Texas businessmen, however, is to ignore all the other things Americans dislike about Texas. When they’re not castigating Texans for plutocracy, moral hazard, and corruption, critics often protest that the state leads the nation in theocracy. This is, after all, a state whose highways are studded with billboards featuring babies who say, via thought bubbles, that they could dream before they were born, and there are occasional roadside clusters of white crosses, graveyards for the victims of abortion. In October traditional haunted houses jostle for space alongside Christian “hell houses”—passion plays about the terrible things that will happen to young people who drink or have sex. The actors are typically local high school students. Most coveted is the role of the girl who, having lost her virginity, screams her way through an abortion as Satan exults from a corner of the tableau.

Texas is the only large state where the religious right has enough power to push the policy agenda. It’s a relatively recent development, and even today, Christian conservatives generally don’t take priority over business interests, but their presence is noticed. “Where did this idea come from that everybody deserves free education, free medical care, free whatever?” wondered Debbie Riddle, a Republican state representative, in 2003. “It comes from Moscow, from Russia. It comes straight out of the pit of hell.”

Yet critics also say Texas has a morally degrading influence on the rest of the country, given its apparent fondness for executions, its expansive prison system, and its proclivity for firearms. No aspect of criminal justice in Texas excites more national and international criticism than the death penalty. Since the U.S. Supreme Court reinstituted capital punishment, in 1976, Texas has executed more people than any other state—493 as of February 2013. That’s more than four times as many as Virginia, the state with the second-largest number of executions, which has put 110 people to death in that time. If Texas were, indeed, a whole other country, it would almost lead the world.

All of Texas’s executions take place in Huntsville—the final resting place of Sam Houston and home to a public university that bears his name. Up the road from the penitentiary, the Texas Prison Museum features several exhibits that celebrate the city’s history, including photos of the old prison rodeos and the electric chair named Ol’ Sparky. Sometimes on execution days a handful of protesters turn up outside the facility. One such group included a pair of black-clad Europeans who had somehow brought the piano John Lennon used while composing “Imagine”; it was sitting next to them on the sidewalk.

Around dusk everyone heads to the building that contains the execution chamber. The front offices feel like a portal to 1960. There’s a picture of John Wayne on the wood-paneled wall. At the appointed hour prison officials, the relatives of the victim and of the offender, and journalists file into a viewing area, where the condemned inmate, dressed for a trip to the hospital and draped in a white sheet, is already laid out on a bed. The victim’s relatives watch from a window on one side of the execution chamber; the offender’s relatives are on the other side. In 2007, when convicted murderer James Clark was asked for his last words, he seemed confused, if not mentally handicapped. “I didn’t know anybody was there,” he said. “Howdy.” There was only one witness on his side of the chamber, an elderly man with spatters of dried paint on his fingernails and a comb’s tooth marks in his hair. The man was crying but trying not to, so that he could smile and wave at Clark as he died.

The process is grim and grotesque. But while polls tell us that Texans are pretty similar to other Americans on most issues, the death penalty is one where we stand apart. According to a November 2011 poll from the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, 62 percent of Americans support the death penalty for people convicted of murder and 31 percent are opposed. A May 2012 University of Texas/Texas Tribune poll, by contrast, found that 73 percent of Texans were either “strongly” or “somewhat” in favor of the death penalty, with just 21 percent opposed.

An outsider could easily get the impression that Texas’s use of the death penalty is in keeping with a generally punitive approach to crime. The state’s prison population is dropping slightly—in August 2012 there were about 154,000 people behind bars, down from 156,500 a year before—but Texas nonetheless has the largest prison population of any state and the fourth-highest incarceration rate in the country. Prison conditions are often overcrowded and unpleasant, and occasionally abusive. Most of the state’s prisons have no air-conditioning, for example; there have been inmate deaths attributed to heat, leading to ongoing lawsuits against the state.

The state’s disproportionate prison population is partly due to disproportionate crime. In several major categories, Texas’s crime rates exceed the national average. But that is also due to the state’s historically draconian approach. Texas drug laws, for example, have been notorious not only for their severity but also for their use in neutralizing people suspected of socially disruptive behavior—that is to say, political types. The most famous case is that of Lee Otis Johnson, a black activist and organizer from Houston who, in 1968, received a thirty-year prison sentence after passing a joint to an undercover cop (he served four years before being freed on appeal). “Criminal mischief” has been another catchall charge used to crack down on perceived troublemakers, usually black or Hispanic ones. That supposed crime, which generally refers to property damage or vandalism, can carry a sentence of up to twenty years.

Not surprisingly, Texans are big on the right to bear arms. They always have been: a grievance that triggered the revolution was that Mexico didn’t want the settlers to be armed. Democrat Ann Richards was one of the few modern governors to be skeptical of Texas’s gun culture. She was tough on crime—she built new prisons and made it much harder to be released on parole—but she also vetoed a concealed-carry bill in 1993, even after advocates tried to persuade her that the law would help women in particular to ensure their personal safety. “Well, I’m not a sexist,” she responded, “but there is not a woman in this state who could find a gun in her handbag, much less a lipstick.” That was during her campaign against George W. Bush, who promised that he would sign the bill. He won, and he did.

MOST TEXANS AREN’T BOTHERED by the state’s strong Second Amendment stance. And many would point out that Texas has actually pursued a number of criminal justice reforms in recent years. But it’s an uphill battle when so many people think your state is, well, dumb. That’s another problem people have with Texas. Never was that clearer than when George W. Bush emerged on the national stage, speaking English the way he does.

“Such frank boobery would seem to represent a culmination of the long, strange history of anti-intellectualism in America,” wrote Mark Crispin Miller, who was moved to write a whole book on the subject of Bush 43’s syntax and diction. “Certainly George W. Bush has always postured as a good ole boy, who don’t go in fer usin’ them five-dollar words like ‘snippy’ and ‘insurance.’ ” In Miller’s view, Bush was a step down from presidents such as Franklin Pierce, who was “fluent in Greek and Latin, like so many of his peers.” Yes, the heady days of antebellum America—black people were held as slaves, women couldn’t vote, and the American buffalo was on the verge of extinction, but at least the affluent white men of America’s political elite spoke Greek so that we didn’t have to be so ashamed of our boobery.

Complicating matters is that Texans themselves seem to go out of their way to offend everyone as much as possible—and if anyone gets upset, they act like it’s the funniest thing they’ve ever heard. Remember that one about secession? It was April 15, 2009, a bright, sunny day in Austin. Governor Perry was at city hall addressing a rally for people who were against the stimulus package, one of the nation’s proto–tea party events. As the governor was leaving, Kelley Shannon, a reporter with the Associated Press, asked him what he thought about the idea that Texas could secede. Somebody in the crowd had shouted something to that effect, and Perry was known to be a big proponent of states’ rights.

“Oh, I think there’s a lot of different scenarios,” Perry replied. “Texas is a unique place. When we came in the Union in 1845, one of the issues was that we would be able to leave if we decided to do that. You know, my hope is that America, and Washington in particular, pays attention,” he continued. “We’ve got a great Union. There is absolutely no reason to dissolve it. But if Washington continues to thumb their nose at the American people, you know, who knows what may come out of that? So. But Texas is a very unique place, and we’re a pretty independent lot to boot.”

In Texas, the comments were greeted with a snort: it was just Perry running his mouth. People in other parts of the country, however, were shocked, maybe because they’re not used to hearing their governors allude to secession or sovereignty. After Perry joined the presidential race two years later, the episode was revived to much fanfare. How could the Texas governor offer himself as a candidate for the president of the very country he was on record as saying that his state was thinking about leaving?

I am a product of Texas public schools, so it’s possible that my reading skills are just stunted. Still, I didn’t see Perry’s comments as a call for secession. “We’ve got a great Union” is the first clue. “There is absolutely no reason to dissolve it” is the second. When pressed for clarification, Perry has repeatedly said that he wasn’t suggesting secession. He’s also indicated that he finds all the hand-wringing to be slightly hysterical, in both senses of the word. PolitiFact Texas, a nonpartisan organization that rates the accuracy of various political statements, has repeatedly sided with the governor on this. There is no serious separatist movement in Texas. The most coherent separatist movement in the United States, as it happens, can be found in Vermont, which likes to think of itself as also having once been an independent republic (it wasn’t).

To be fair, there are a lot of Texans, including the governor, who seem to think that Texas could leave the Union if it wanted to, although it can’t. (There’s a consensus among constitutional scholars that the Civil War put that question to rest.) A 2009

Rasmussen survey found that 31 percent of Texans believed their state had the right to secede. More ominously, 18 percent said they wanted to leave the Union.

That might look like evidence of a rabid revolutionary movement. As it turns out, however, it’s not just Texans who think their state can secede. A June 2012 Rasmussen poll found that 24 percent of Americans think any state has the right to come and go freely. All of these polling results should, of course, be taken with a grain of salt; there’s no penalty for mouthing off to a pollster. But as for those Texans who told Rasmussen that they wanted to leave the country? A Research 2000 poll, taken in 2009 for the liberal politics site Daily Kos, showed that about 80 percent of Americans said their state would be better off as part of the Union. The South was the outlying region in that survey: only 61 percent of Southerners were sure they wanted to stay, and 9 percent thought their state would be better off as an independent country. The rest, 30 percent, weren’t sure, which sounds about right. A Republic of Alabama would have some problems. Texans are more confident about their ability to go it alone, even if they’re nonetheless pro-Union.

Still, the belief that Perry was calling for secession has been incredibly persistent. At times it even seems as if some Democrats are trying to gin up controversy for political purposes. In June 2012 Martin O’Malley, the governor of Maryland, told reporters that Republican governors were threatening to secede in response to the Supreme Court’s decision to uphold the health care reform bill. “Some of our colleagues would like to get out of being members of the Union,” O’Malley said, according to Politico. “And by that, I mean the United States. So I think, who can predict what some of the ewoks on their side of the aisle will choose? I don’t know.” He didn’t call Perry out by name, but he might as well have. Perry’s press secretary had said that the governor had “absolutely no interest in accelerating the implementation of Obamacare.” By the going evidentiary standards, that’s basically proof that Perry was holed up in the Capitol jumping on his desk and firing pistols in the air.

THE IDEA THAT TEXAS wants to secede is apparently ingrained—that’s why the online petition got so much attention. In reality, there was nothing unusual about it. Hundreds of thousands of disgruntled Americans in other states had signed similar petitions; every state had one. Texas was bound to have more signatures than most states. The reason is obvious, and it’s the same reason that Obama got more votes in Texas than he did in deep-blue Massachusetts or his home state of Illinois: there are a lot of people in Texas. And by the way, a genuine secessionist would scoff at the idea of signing an online petition on a White House website.

There’s a sad irony in the situation, which is that all the talk about secession ignores the fact that Texans have, at times, been more committed to the Union than anyone else. Last year, for example, New York Times columnist Gail Collins published a book about Texas that includes an account of the April day described earlier. In it, she mentions that Perry quoted Sam Houston: “Texas has yet to learn submission to any oppression, come from what source it may.” For Collins, this was evidence that Texans might actually be in favor of secession. “When Houston made that remark,” she writes, “he was definitely attempting to break away from the country to which Texas was then attached.”

Actually, Houston made that claim in a speech to the U.S. Senate about the U.S. Army’s occupation of Santa Fe, in the New Mexico territory, following the Mexican-American War. The borders of Texas were a catch-as-catch-can affair at that point. Houston thought part of the New Mexico territory should go to Texas, but his main point was that Texas’s concerns should be addressed before, say, California’s. Texas had been annexed earlier and had been waiting to settle its borders for several years. In other words, Houston wasn’t threatening to break away from the United States; he was arguing that Texas had rights because it was part of the United States.

As the speech went on (and on), Houston shifted gears to address issues closer to home for the assembled senators. This was July 1850, and the month before, delegates from nine slaveholding states had met in Nashville to try to figure out what they would do if the federal government decided to ban slavery in the new Western territories. The Nashville Convention, Houston said, was unconstitutional. States weren’t allowed to make deals among themselves without congressional approval, so the whole thing was “ridiculous flummery.” For his part, he added, he was committed to the Union, and Texans felt the same way: “Think you, sir, that after all the difficulties they have encountered to get into the Union, that you can ever whip them out of it? No, sir. . . . We shed our blood to get into it, and we have now no arms to turn against it.”

It’s easy to see how this particular misunderstanding could arise. There’s no reason a person from Ohio or Oregon would have a sideline in this particular subject, and Texas did secede from the Union once, despite the efforts of leaders like Houston (who eventually resigned his post as the governor of Texas rather than serve as a governor in the Confederacy).

This brings us to the crux of the issue. The state seems to induce a sort of collective confusion, like a political version of body dysmorphic disorder, that isn’t doing either the state or the country any favors. Let’s go ahead and say that we, as Texans, are primarily responsible for our own reputation. Why not? Maybe it’s true. We do, after all, have a high tolerance for bragging and bluster. Sometimes we even take pleasure in it as a sort of sport. “It’s a long-held theory of mine that politicians should provide public entertainment,” wrote Molly Ivins in Shrub, her book about George W. Bush, and she gave him high marks in that respect at least. Other public figures provide similarly good value. In 2012 Drake, a Canadian rapper, shared a personal experience on Twitter: “The first million is the hardest.” He was summarily retweeted by T. Boone Pickens, the oilman from Amarillo, who appended his rejoinder: “The first billion is a helluva lot harder.”

For that matter, Texans sometimes scold other people for being overly polite or chicken. Here’s Perry again, on the 2010 sinking of the South Korean ship Cheonan: “The United Nations responded with its characteristic force, passing yet another resolution expressing displeasure.”

At the same time, Texans occasionally go so far that even Texans are offended. In 1990 Ann Richards famously got a boost in her bid to become governor after the Republican nominee, oilman Clayton Williams, compared rape to bad weather: “If it’s inevitable, just relax and enjoy it.” That wasn’t a flippant response to a question about sexual violence, by the way. He had some reporters out to his ranch, and it was fixing to rain, which reminded him of his favorite rape joke. Richards herself was no knuckle-dragger, but she did have a sharp tongue that sometimes got her into trouble. Her jabs about the Bushes—she famously said that H.W. was “born with a silver foot in his mouth”—were treasured by Democrats. When the comparatively mild W. beat her in the 1994 gubernatorial election, however, some observers admitted that the ridicule might have been a factor in turning voters off.

So if Texas pols manage to offend Texans, it’s no surprise that national audiences might be turned off. In 2011, while running for the Republican presidential nomination, Perry said that if Ben Bernanke came to Texas, he would be treated “pretty ugly.” Some pundits took the remark as a threat to lynch Bernanke. That seemed like a real non sequitur, not to mention somewhat unfair to Perry, who had signed a hate-crimes law in 2001 and who managed, in any case, to leave Bernanke in peace after that. Still, it was a boorish thing to say, and silly; whatever your feelings about quantitative easing and monetary policy, neither was “almost treasonous,” as Perry put it.

Outsiders often have a hard time discerning the cultural factors behind Texan behavior, but Texans can’t necessarily see what outsiders are seeing either. Here’s a quick quiz: When Texans talk about leaving the Union, what historical experience are they fondly evoking? If you said “the Republic of Texas,” congratulations, you’re a Texan. When Texans talk about secession, or being independent, or not needing Washington, we’re referring to the Republic of Texas. That’s obvious to most of us.

What’s not obvious is that other people don’t see it that way. At least, it wasn’t obvious to me until a couple of years ago, when I was asked to write an article for a Washington-based publication about Perry’s rhetoric. When I got the edits back, I saw that the editor wanted to add a parenthetical about how the governor’s comments were clearly a callback to Texas’s years in the Confederacy.

In other words, citizens from California to Maine seem to have the impression that this is a state full of gun-toting Bible-thumpers and crypto-Confederates who have their oily fingerprints all over American politics and policy. That’s why they don’t always seem neighborly, why sometimes they even exult when Texans stumble. In 2011, when wildfires destroyed hundreds of homes in Central Texas, lots of people thought of the same joke: Texans should have prayed harder for rain. When Enron imploded, you could have cut the schadenfreude with a bowie knife—the weapon described by one early visitor, from Great Britain, as “the tenant of every Texan’s bosom, and which should be deposited (dripping, as it is, with human blood) in the museums of Europe, and placed by the side of the weapons of the benighted Indian of the desert as an emblem of the savage barbarism of the Anglo-American race.”

Goodness. How often are Floridians scolded for the fact that their state single-handedly screwed up the 2000 presidential election? Do Iowans feel guilty over the agricultural subsidies that exacerbate hunger around the world? And just think about all those people who are living in New Jersey and getting off scot-free.

Texans, however, are routinely asked to account for guns, the death penalty, the prison-industrial complex, the savings and loan crisis, George W. Bush, Karl Rove, Enron, Halliburton, Tom DeLay, Rick Perry, the Confederacy, the Republican party, the religious right, the war in Iraq, the war in Afghanistan, war in general, stupidity in general, and the fact that Texans ride horses to school.

Yes, this is unfair. What’s worse is that it’s not productive. Texas might not be a role model for every state, but a lot of places could use a little more of our spirit, drive, and determination. The United States isn’t doing itself any good by keeping its scrappiest state at arm’s length, and we can’t say it’s their loss; Texans are Americans, and so it’s ours. If our friends across the country are determined to be suspicious, the right thing to do would be to respond to their concerns with courage and with love. There are, of course, bragging rights at stake.

Apapted from Big, Hot, Cheap, and Right: What America Can Learn From The Strange Genius Of Texas, to be published by Public Afffairs. ©2013 By Erica Grieder.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Rick Perry