This week, and for the rest of the early voting period for this fall’s off-year election, Texas voters will be casting ballots on a subject that sounds like one of the weightier considerations a citizen can be asked to make: whether or not to approve eight new amendments to the Texas constitution. However, as off-year-voting enthusiasts already know, while the issues that are presented before voters are often a priority to someone, somewhere, they’re not exactly hot-button issues of the day.

This year, for example, the first proposition on the ballot concerns rodeo raffles. Shall the right of rodeo organizers to hold raffles at their events without fear of being prosecuted for illegal gambling be enshrined into the foundational document of this great state, ratified in 1876? If you’re wondering why you (undoubtedly one of those dedicated voters) are being tasked with making that decision, the answer is, like so many things in the Lone Star State, both surprisingly complicated and downright quirky. Let’s take a spin through the ol’ Texas constitution and learn what’s going on with the living document that begins with the majestic words “That the general, great and essential principles of liberty and free government may be recognized and established, we declare,” and ends with the rather less inspiring “This temporary provision expires January 1, 2022.”

The Stakes

The eight amendments before voters right now largely serve what we, without any judgment, would describe as niche interests. For example: Proposition 1 would allow rodeos to hold raffles. This is very important to you if you are a cash-strapped rodeo organizer! But it’s less so for those of us who are not. Most of the rest are similarly narrow in scope: Proposition 8, which would create a homestead tax exemption for the surviving spouse of a military member killed while serving in a noncombat capacity, such as a car crash, would affect fewer than ten families per year. The amendment with perhaps the broadest impact, Proposition 3, would prevent government officials from limiting access to religious services. That’s a response to the stay-at-home orders from local officials in some parts of the state in the early weeks of the pandemic—not something that many Texans have given a great deal of consideration to, at least outside of a narrow stretch of time during the unprecedented events of last year.

Why are you—as someone who presumably has not given much thought to rodeo raffles or homestead tax exemptions or precisely how much discretion local officials need during a crisis—being asked to weigh in directly? The answer lies in the weird history of our state constitution.

The History

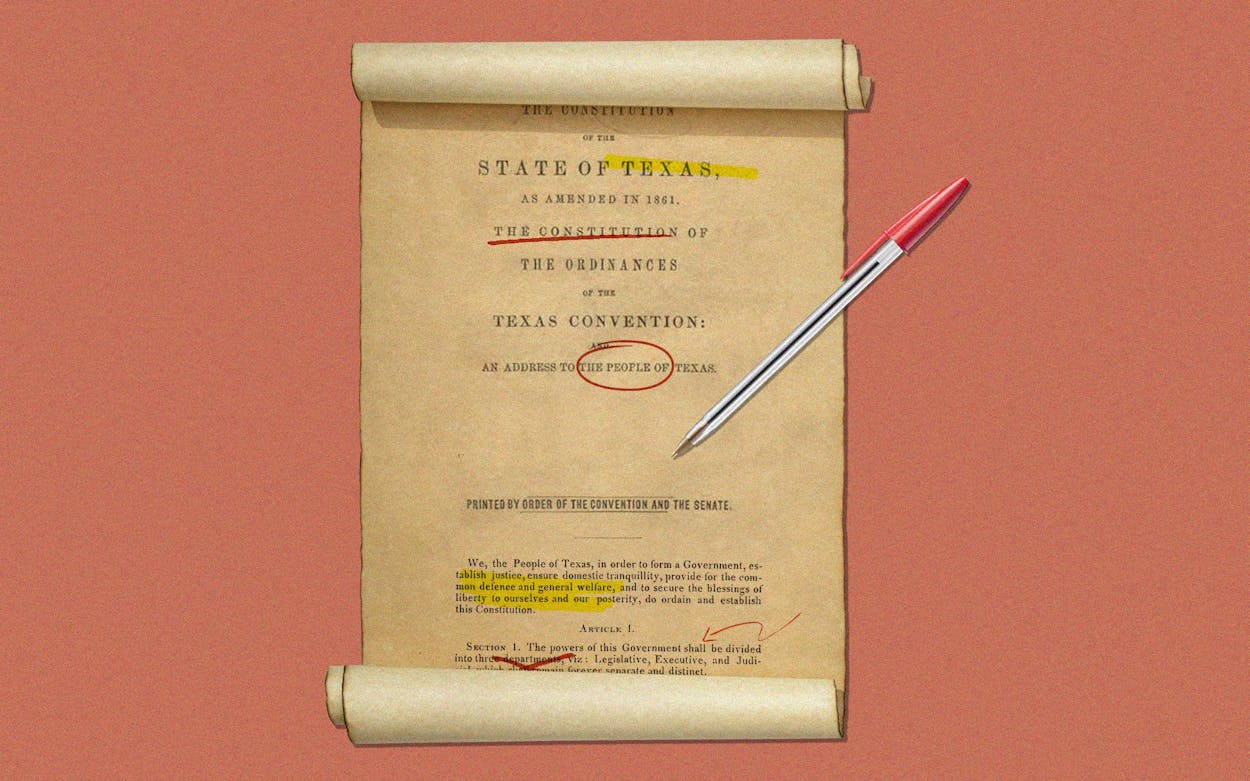

The Texas constitution is the seventh foundational governing document that the state has used. The first—the 1827 constitution of the state of Coahuila y Tejas—was adopted while Texas was still part of Mexico, while the second, the 1836 constitution of the Republic of Texas, was written pre-annexation. The 1861 constitution of the State of Texas, meanwhile, was written while Texas was part of the Confederacy. The document was then rewritten (and rewritten, and rewritten) for a few reasons. The 1866 constitution was designed to be consistent with that of the United States, which Texas was rejoining; the 1869 constitution was written under the orders of federal military officers, and begins on a note of forced humility—“that the heresies of nullification and secession, which brought the country to grief, may be eliminated from future political discussion”—while the 1876 constitution was written to more accurately reflect the popular sentiment in Texas at the time. And then, once Texas decided to stay put in the U.S. for the next century and a half (and counting?), there was less need to throw the whole document out and start over.

If you’re curious what all of these documents look like, by the way, UT’s Tarlton Law Library has a gallery of digital images. These are mostly what you are probably imagining when you think of a constitution: forty pages or so, outlining some values that the authors believe Texas’s government should aspire toward.

However, one provision in the Texas constitution that has been in effect from 1876 until today is the reason why you’re voting on whether the rodeo can hold a raffle: the state only has powers that are explicit in the document. Does the Legislature have the authority to grant rodeo administrators the right to raffle off an F-150? Not unless and until voters add Proposition 1 to the constitution. The U.S. Constitution, whose Article I, Section 8, grants Congress the power “to make all laws which shall be necessary and proper” is the reason the federal government doesn’t have to jump through similar hurdles. But it’s not unusual among states: there are 24 whose constitutions have been amended more than 100 times, while others have hardly been touched (West Virginia’s, for example, has been amended only 20 times since 1872, compared with Texas’s 507 since 1876).

The Context

The Texas constitution, in its latest 2019 form, is 100,388 words long, or just a smidge longer than El Paso literary giant Cormac McCarthy’s misunderstood masterpiece All the Pretty Horses. By contrast, the U.S. Constitution is a breezy 7,500 words. While there’s plenty of aspirational language to be found in the state constitution (“All political power is inherent in the people, and all free governments are founded on their authority,” is a good one), there’s also just an absurd amount of housekeeping in the document. Does the word “football” appear in the Texas constitution? Absolutely it does. (So does “NASCAR”! They both appear in Article III, Section 47, which was amended in 2015 and 2017 to allow certain sporting event organizers to hold raffles—a provision that, alas, neglected to specifically include rodeos.) What about “horse”? You know it, buddy. (Article III, Section 52l, added in 2019 to allow law enforcement agencies to donate a retired animal to its handler.) “Cocoa”? Oh yeah. (Article VIII, Sec. 1n, 2001, exempted from sales tax in its raw form.)

If all eight amendments pass this fall, we still won’t hold the national record: California’s constitution, to pick just one random example, has been amended 516 times as of 2020, narrowly edging us out. But nobody can compete with Alabama: Its constitution has been amended 977 times and runs 388,000 words long, making it 20,000 words longer than Lonesome Dove.

What It Means

In the short term, it means that you, the Texas voter, will weigh in on stuff that probably does not really feel like it’s any of your business. It also means that bereaved military families in need of property tax relief, among others, are dependent on the goodwill of voters to have their needs met. Luckily for them, the weirdness of putting this all up to a vote means that proposed amendments usually tend to pass. Since 1876, three quarters of proposed amendments to the Texas constitution have made it into the august document. Partly that’s because off-year elections tend to be low-turnout elections in which voters who do have a strong interest in what’s an otherwise niche issue can have a disproportionate say, and it’s probably also because most voters look at a question like “should rodeo organizers have the right to hold raffles” and think, “Sure, no skin off my nose.”

In the last five constitutional amendment elections, there have been 34 proposed amendments, and 33 of them have passed. (A 2019 measure that would have allowed a person to hold more than one office as a municipal judge at the same time failed by 31 points.) Some years are better for the proposed amendments than others—in 2011, three of the ten on the ballot failed. Sometimes the failed amendments come about because of the statewide nature of the process—for instance, one of the 2011 amendments was narrowly tailored to allow El Paso County to issue bonds to pay for the development and maintenance of parks. Voters around the state rejected the initiative by fewer than three points, despite El Paso voters approving of it by a 7-point margin.

Could a similar defeat happen here? It’s certainly possible! Proposition 3—which would permit church services to carry on despite public-health perils—is opposed by most newspaper editorial boards in the state. And according to Ballotpedia, no one has spent any money trying to persuade voters to pass it—or any other amendment, for that matter. But history tells us that in an election for which only a tiny handful of voters is expected to turn out (a safe guess might be around 10 percent of registered voters), and only a handful of the measures are likely to prove controversial, the odds are that all or most will pass. Is that good or bad for Texas, or its rodeo organizers, or the other assorted folks who will benefit or suffer depending on what happens? For better or worse, that’s up to you.