This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

On September 3 retired superspy Bobby Ray Inman surprised the directors of Microelectronics and Computer Technology Corporation (MCC) by revealing that he would leave his position as chief executive officer of the Austin high-tech consortium at year’s end. Ever since, there have been two consuming questions: Why did Inman leave? What does his departure mean for MCC?

It has been less than four years since Inman announced that MCC would set up shop in Texas. Austin lured the research facility after a high-profile bidding war among 57 cities in 27 states. Texas’ multimillion-dollar package of inducements to MCC—a joint venture of billion-dollar U.S. corporations—included the use of a Learjet, a $2-a-year lease on a new 200,000-square-foot office building, and cut-rate home mortgages for MCC researchers. But MCC’s promise seemed worth the price. With the consortium as a magnet, went the scenario, Austin would become a kind of Silicon Valley with spurs. Neal Spelce, a public relations executive who helped court MCC, compared the announcement’s impact with that of the decisions to locate the University of Texas and the state government in Austin.

These days the words to the high-tech tune have changed. “Hype, hype, hype,” says Austin Chamber of Commerce president Lee Cooke about the forecasts that microchips would transform Austin. “If we learn anything from Silicon Valley, we ought to learn how not to do what they did. It created tremendous toxic problems, tremendous traffic problems, tremendous cost-of-living problems. I don’t think high tech will ever be our savior.”

Inman leaves with MCC up and running but its lofty promise unfulfilled. The central purpose for the consortium—to produce cutting-edge technology to help the companies compete with Japan—remains well short of fruition in MCC’s long-term research program. The $23.5 million private fundraising effort to cover a part of the inducements remains millions short of its goal. And the spin-off effects so widely anticipated have yet to materialize. The magic about MCC has faded and reality has set in, revealing the research facility as it has always been: a fragile, high-risk venture whose value will not be known until the nineties. And with the departure of Inman—a charismatic force in business and politics—MCC’s public influence will diminish. Inman’s departure certifies the end of the Austin high-tech boom, a phenomenon that was always more illusion than reality anyway.

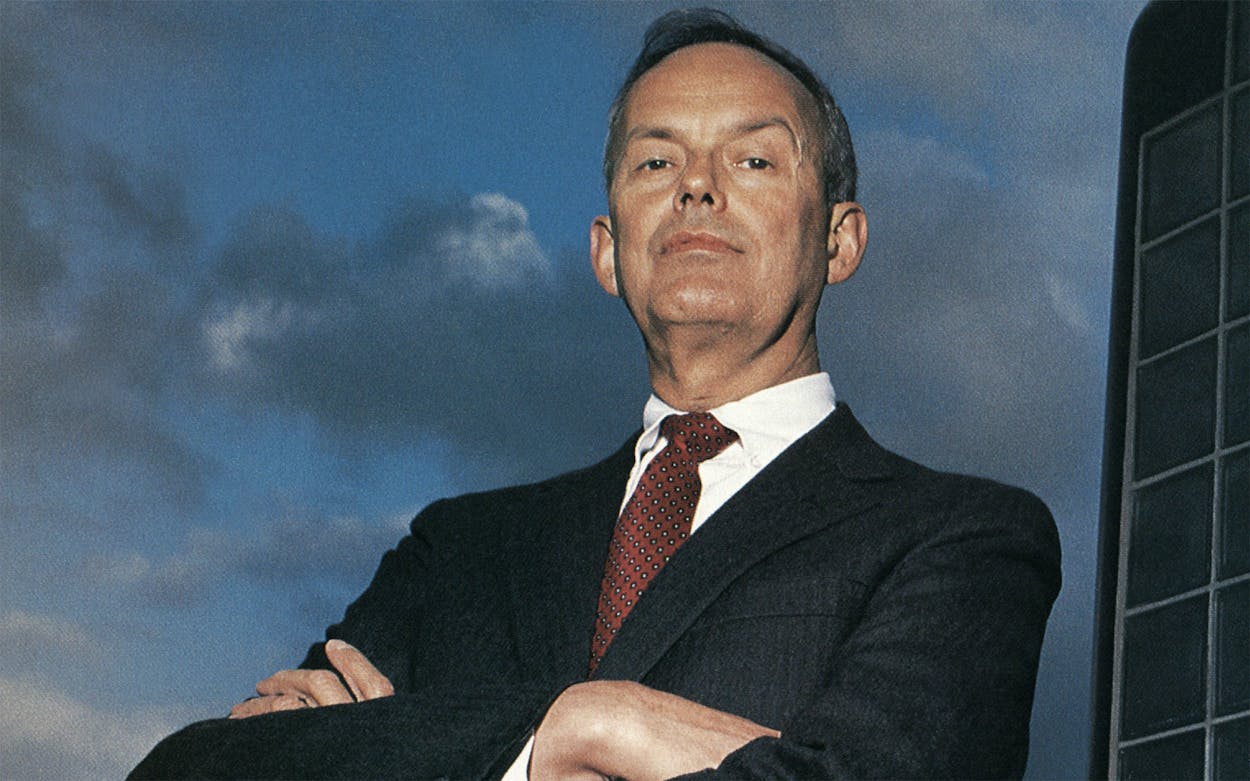

MCC drew massive attention partly because it was the first such U.S. consortium—others have followed—but largely because of Inman. The MCC chief brought to Texas a rare trait for a business executive: star quality. A retired four-star admiral, 55-year-old Inman had previously served as director of the National Security Agency and as deputy director of the CIA. Inman’s eloquence, expertise, and willingness to speak his mind on everything from national defense to Texas culture made him a media darling. He appeared frequently on ABC’s Nightline, and in Texas he seemed ubiquitous. There was Inman in Austin, lamenting the poor ranking of the Texas public education system. There was Inman in Salado, speaking at a conference on Texas myths. There was Inman at the Megatrend Cities in the Eighties conference in Austin, defending the maligned developer. It was Inman again, before the Austin chapter of the Association of Industrial and Office Parks, speaking out for the small businessman by bemoaning the recent eviction notice issued to the four-chair barbershop where he had his hair cut.

The Texas establishment embraced Inman instantly. Lieutenant Governor William P. Hobby, Jr., invited him to address the Texas Senate. He became a director of Fluor, Texas Eastern, Tracor, Southwestern Bell, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, while UT named a $1 million professorship for him. Inman wielded influence in state politics, particularly on higher education. To lure the consortium, UT added millions to its budget for computer science. When higher education cuts were contemplated in 1985, Inman calculatedly told the Dallas Morning News that he would have to “think very carefully” about whether to recommend Texas if MCC were choosing its site at that time. The remark prompted a meeting in the Governor’s Mansion, where Mark White and Hobby accepted Inman’s advice to alter the way state science research grants are distributed. Hobby says that Inman personally drafted the bill rider that instituted the change.

While MCC was influential, it could not fulfill the expectations that it would attract thousands of high-paying high-tech jobs. The research consortium is credited with drawing a handful of new companies to Austin and encouraging the expansion of a few more already there. But because of a slump in the electronics industry, others have cut back their Austin operations or left town altogether. High tech today employs but 8 per cent of Austin’s work force. By one measure, says chamber of commerce chief economist Angelos Angelou, the percentage of the region’s jobs represented by high tech has dropped since MCC’s announcement.

In the short term for Austin, in fact, MCC has been as much a curse as a blessing. The May 1983 announcement spurred a frenzy of real estate speculation that inevitably collapsed, driving developers out of business, damaging banks, and inflating Austin’s housing costs. When MCC chose Austin, the city was already absorbing as much growth as it could handle. “We were running at ninety per cent open,” says Cooke. “MCC put us over the top. It accelerated our problems.”

Lost in the hoopla over MCC’s arrival was its conception as a long-term enterprise. MCC’s research programs all have timetables of six to ten years. The company takes on extraordinarily complex problems relating to computer speed and flexibility, artificial intelligence, software development, and integrated circuits—problems they may never solve. “The great overhype, the great overreaction, was the expectation of instant results,” says Inman.

And though the consortium is now running well, its future is in no way assured. Companies are free to drop out with one year’s notice, and while MCC’s membership has grown from 10 in 1983 to 21 in 1986, the lineup has shifted. One company, BMC Industries, is leaving at the end of the year after encountering financial trouble and falling behind on its payments to the consortium. Mergers and industry money woes have resulted in other withdrawals and will remain a constant threat to MCC’s existence.

Indeed, it is to Inman’s credit that he has taken MCC this far. Brought together by the fear of Japanese competition, its shareholder companies are usually bitter competitors, wary of sharing information. Setting up ground rules for MCC’s operations required, as Inman puts it, “some tough head-knocking sessions.” Inman’s negotiating skills, media savvy, and political contacts made him the perfect man to start MCC. He leaves partly because that job is finished and because he fits less well into the job that lies ahead. Thus his departure is an example of masterful timing. Inman, who had originally committed to MCC for only three years, leaves amid much praise for having established a top-flight research organization—but before MCC must make good on its two most difficult tasks: producing revolutionary technology and persuading the shareholder companies to use it.

Despite the long-shot nature of MCC’s projects, Inman is confident that the consortium will produce dramatic breakthroughs. “Lots of exciting things are already bubbling up,” he says. He is less certain that the shareholders will transfer the technology from the lab to the production line. American companies are fabled for their adherence to the N.I.H. (“not invented here”) syndrome, a reluctance to make use of research developed elsewhere. “The real concern I have is, will the companies gear up to use the technology?” says Inman. “I’m not sure all of them are preparing aggressively to receive what’s coming. My worry from the outset has been that we’d be producing technology two or three years ahead of the marketplace, ahead of the Japanese, and we’d all show up in the marketplace at the same time.” If MCC’s new technology never pays off for the shareholders—who will invest $75 million in MCC in 1987—the consortium will be considered a failure. MCC can do no more than to encourage the companies to use the technology, and that fact frustrates Inman. He says he is leaving MCC in part so he can operate from “that side of the fence.”

Inman plans to become chairman of Westmark Systems, which is a new Texas-based private holding company established to purchase defense-industry electronics firms. Controlled by Mason Best Company, the merchant banking firm started by former InterFirst Bank chairman Elvis Mason and Houston entrepreneur Randy Best, Westmark will seek to acquire companies that will develop “leading-edge” technology, according to Inman. The board of the privately held corporation Inman will run reflects the powerful circles in which he travels. It includes former Secretary of Transportation Drew Lewis, former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, and former Democratic National Committee chairman Robert Strauss. Though Inman will certainly be courted by both political parties, he denies any plans to seek public office. He says he will remain in Austin, where he has bought land on which to build a new home.

Who will succeed Inman? Several MCC directors, anxious for the consortium to start producing major developments in the next two or three years, say they hope to find a chief executive with more technical expertise (despite his years in intelligence work, Inman has no formal technological training; his only degree is a bachelor’s in history from UT). “I don’t think his departure at this stage is that crucial,” says Irwin Dorros, executive vice president of Bell Communications Research, who believes that “somebody closer to the technology who will have a firsthand feel for its impact is a stronger need.” Says Gerald Dinneen, corporate vice president of Honeywell, “We can look for somebody who has different skills. We need someone who has a good understanding of industrial research and development and of the markets in which the shareholders work, so they can structure the program to meet their needs. The time has come to focus in on set programs and to carry them out.”

Inman’s departure and his probable replacement with a lower-profile technical figure will inevitably reduce MCC’s clout. It was the retired admiral, not the computer consortium, that was the influential force. “As far as I’m concerned, the institution is Bobby Inman,” says Hobby. “I don’t know a single other person who is connected with it.”

So MCC will continue quietly into an uncertain future, under diminished—if more realistic—expectations. “We never had any expectation that this was a special elite thing that was going to be the panacea for all our problems with Japan,” says Dorros. “This is yet another step. It’s a good step.” Similarly, the expectation that MCC would magically make Texas competitive with Silicon Valley and Boston’s Route 128 was always unrealistic, particularly given Texas’ comparatively weak university system. MCC is a start, but it is up to Texas’ business and government leaders to do the rest. “Austin still has the potential for being one of the significant emerging high-tech areas in the United States. An MCC can get you great national attention worth a megamillion-dollar advertising campaign,” says Inman. “But you’ve got to do a lot of other things to sustain that.”

- More About:

- Business

- TM Classics

- Austin