This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

As Alice Sessions remembers it, the trouble began as soon as her husband, Bill, was named director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, years before the backstabbing and intrigue became public knowledge. In September 1987 she and Bill were flying first-class from San Antonio to Washington, D.C., where he would soon be sworn in. Bill said he felt ill and went to the lavatory in the front of the plane. Suddenly he vomited into the sink and fell back through the lavatory’s unlocked door into the aisle. Pandemonium ensued. A covey of FBI agents scurried to get to him. So did Alice. As agents and a doctor tended to him on the floor, flight attendants had to climb over seats to reach oxygen because a food cart blocked the way.

When Bill came to, Alice told the agents that her husband hadn’t been eating right, that there was nothing wrong with him that a bowl of soup and a decent night’s sleep wouldn’t cure. But they would not listen. When the plane touched down in Washington, Bill was whisked away to one FBI car and Alice was put in another. Agents took her to an apartment that was to be her temporary home, where she warmed a can of tomato soup, assuming Bill would soon arrive. Nearly half an hour passed. No one communicated with her. Finally she asked the agent stationed in her home where her husband was. The agent had no information, but a phone call established that Bill had been taken to a local hospital. She demanded to be taken there immediately. When she arrived, she was startled to see Bill, looking pale and lifeless, laid out on a gurney in the emergency room. “They told me he had a bleeding ulcer and had lost two pints of blood,” said Alice, “but I always suspected it was something else. I can’t shake the feeling they might have given him bad medicine.” From that moment on, the wife of the FBI director could not help but think that a few agents in the Bureau were out to get her husband.

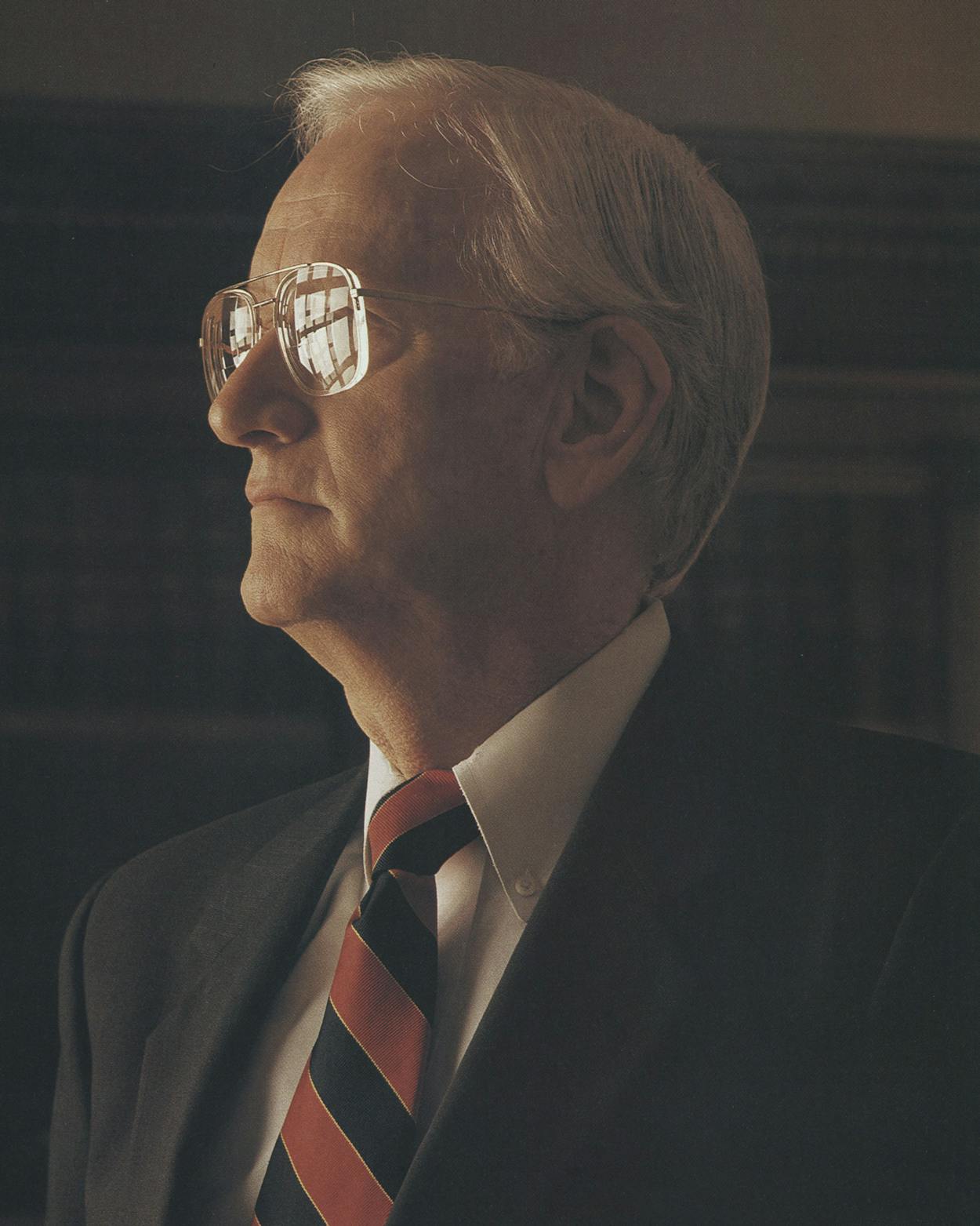

On the seventh floor of Washington’s J. Edgar Hoover Building, the imposing and impregnable headquarters of the FBI, William Steele Sessions stood alone in his spacious office and stared out a window. It was the first week in March, and Sessions had been fighting to hold on to his job for nearly two months, ever since outgoing U.S. attorney general William Barr issued a scathing memorandum reprimanding him for abusing the privileges of his position. Wearing a dark and unobtrusive pin-striped suit, with one hand tucked in the pocket of his jacket, Sessions had the alternately proud and aggrieved look of a man who believes in his own innocence but knows his destiny is in the hands of a power outside himself—in this case, the White House, the media, and enemies inside his own agency. “There’s Mother Justice,” sighed Sessions, pointing at the Department of Justice building across the street. “No matter what happens to me, I still believe in her.”

Sessions was a federal judge in San Antonio when he was named by Ronald Reagan to a ten-year tenure as FBI director. A moderate Republican, he was known as a straight arrow, and his appearance enhanced his reputation. On the bench, he never slouched; he kept his shoulders back, his back straight, and his chin held high. No one was allowed to chew gum or talk loudly in his courtroom. Sessions has always been such a stickler for the rules that Barr’s memo came as an utter surprise to all who knew him. Even though most of the charges seem petty when compared with scandals such as Iraqgate—many involve taking Alice with him on trips—the spectacle of an attorney general’s attacking the head of the FBI created a sensation. The Washington press corps smelled blood.

Sessions’ future is now in the hands of President Clinton and his new attorney general, Janet Reno. In late March many newspapers quoted unnamed sources saying that Clinton would replace Sessions as soon as the cult standoff in Waco ended. Massachusetts judge Richard Stearns was mentioned as a possible successor. The last weekend in March, Clinton himself joked about replacing Sessions at the Gridiron Club dinner in Washingon—while Sessions was in the audience. “I might have to pick an FBI director,” deadpanned Clinton, “and it’s going to be hard to fill J. Edgar Hoover’s pumps.”

Who would have thought that a sitting president would ever joke in public about the late FBI director’s rumored homosexuality? Then again, who could have anticipated the enormous amount of intrigue that has plagued the FBI since Hoover died 21 years ago? The Bureau still enjoys the heroic image it had under Hoover. Its motto—“Fidelity, Bravery, Integrity”—is chiseled on a statue in the courtyard of its headquarters in Washington, and guided tours of the building are one of the city’s biggest attractions. Yet the inner workings of the FBI are as much a mystery today as they were in Hoover’s day. It continues to be a closed shop, a hidden world of spooks and counterspooks. Five of the six directors since Hoover—including Sessions—have come from outside the FBI, and all five have encountered resistance from the small cadre of lifelong Bureau professionals who regard it as their fiefdom.

Sessions’ troubles provide a view of the FBI’s underbelly. His defenders—who include many critics of the Hoover regime—say the problem is not Sessions but the insular nature of the FBI itself. They wonder why the government has directed so much of its vast firepower at William Sessions, a man so honest that he brings paperclips back to the office.

According to his defenders—chief among them Democratic representative Don Edwards from California, the chairman of the House subcommittee that oversees the FBI, who says Sessions is the best director it has ever had—Sessions did three things to anger the Bureau’s old guard. First, he publicly befriended Coretta Scott King, the widow of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who himself was spied on and lied about by Hoover’s FBI. Second, he agreed to hire more black, Hispanic, and Asian agents as part of an out-of-court settlement of a discrimination lawsuit against the Bureau. Third, he publicly ordered the FBI to investigate the role of the Central Intelligence Agency and the Justice Department in Iraqgate.

In the end, we may never learn whether a rogue group within the FBI deliberately set out to destroy William Sessions, as he and Alice believe, or whether the entrenched culture of the FBI was too much for an outsider to handle—especially an outsider with a gabby wife. Of all the intrigue surrounding the FBI, the most fascinating involves the role played by Alice, who has worked behind the scenes to defend her husband, secretly telephoning reporters and Washington power brokers even when Bill didn’t want her help. The inside joke in Washington is that Alice Sessions is the first strong wife the FBI has had since Clyde Tolson, Hoover’s alleged homosexual lover. “No wonder so many of the old guard can’t stand me,” she said.

The sign posted on Alice Sessions’ refrigerator in the kitchen of her colonial-style brick home outside Washington reads, “Dull Women Have Immaculate Houses.” As if to underscore the point, Alice was wearing a floppy navy-blue sweat suit and maroon slippers. Her short wispy gray hair spiked in all directions. As she bent down to remove a sheet of just-baked sugar cookies from the oven, words tumbled from her mouth and her highly arched eyebrows moved furiously up and down across her brow, as if her body was rushing to keep up with the beat of her brain. “Remember what Chekhov said about playwriting,” said Alice. “Chekhov said if somebody is going to be shot in the last act of a play, then you have to see the gun in the first act.”

Alice walked toward the living room, carrying a plate of cookies and a pot of coffee. The 62-year-old first lady of the FBI settled herself on a pale blue couch. “When I saw Bill lying on the floor of the airplane and when they took him to the hospital was when I first saw the gun in our drama,” she said. “I realized then that the FBI was going to try and separate us, and under no circumstance could I allow that to happen. ”

Even before the plane trip, Alice had tangled with the agents who were sent to San Antonio to help ease Bill’s transition from the calm, sedate life of a federal judge to the faster, more dangerous track of an FBI director. The first dispute was over who would be invited to the swearing-in ceremony; Alice had her list, and the FBI had its own. She and Bill had been married for 35 years, and Alice had always micromanaged the details of his official life, whether he was a private lawyer in Waco or a U.S. attorney in San Antonio or a judge. “Bill Sessions is a person who has a set routine,” she explained. “He wakes up at seven, makes his own bed, has oatmeal and juice, and is out the door by seven-thirty. He needs this kind of routine to function well, and he needs three square meals a day. Almost from the beginning, the agents that came to San Antonio tried to make him run on their schedule. For a while, he was living on nothing but Coca-Colas and aspirin.”

Half a decade in the company of spooks has clearly taken its toll on Alice Sessions. In the eleven years that she and Bill lived in San Antonio, Alice was always arty and eccentric but never foolish or over the edge. She earned a master’s degree in theater, raised four children with no household help, and often telephoned the classical radio station when its disc jockeys mispronounced the names of composers. No one who knows her has ever accused her of being paranoid. Her conclusion that veteran FBI agents might be going to great lengths to force her husband out of his job reflects the stress of living within what is known as the security envelope. Sometimes, Alice Sessions has found, it is impossible to tell the good guys from the bad.

For instance, about a year after Bill was on the job, Alice came home one day and found Ron McCall, the chief of the director’s security detail, upstairs in her husband’s bedroom. Although she did not know what McCall was doing, Alice had the impression he was bugging the house. “The front door is right down the stairs,” she told him. “Get out.” The agent left without a word and has refused to comment on the incident. Later Alice clashed with McCall when she found out he had 25 keys to her house and planned to give them to other people in the Bureau. Six months later she had every lock in the house changed. “Early on, I realized the security people were trying to manage and contain us, not protect us,” said Alice.

If there is any single issue that illustrates how Bill and Alice Sessions got crosswise with the FBI’s veterans and with George Bush’s Department of Justice, it was the debate over how to replace a picket fence in their back yard. McCall and his boss, Floyd Clarke, who is Bill’s deputy, wanted an expensive eight-foot iron security fence that extended all around the property. Bill and Alice wanted a simple wooden fence around the back yard. Several meetings were held, and finally the wooden fence was built at a cost of nearly $10,000, far less than the iron fence would have cost. On January 12, when the Justice Department and the FBI issued their reports on Sessions, the trivial dispute about the fence merited 36 of 161 pages. The wrongdoing, Barr argued, was that the wooden fence was decorative rather than secure and thus constituted a private perk funded by the public.

Compared with John Sununu’s use of Air Force planes to jet around the country on ski trips, the sort of abuse Sessions was accused of was so penny-ante as to be ludicrous. For instance, Sessions was accused of using an FBI plane to haul firewood from New York City to Washington. As Sessions tells it, what happened was that after an official trip to New York, he brought back four sticks of aspen, which Alice later placed beside her fireplace for decoration.

The reports also accused Sessions of dodging his taxes. To avoid having his limousine rides to and from work considered a taxable benefit, Sessions put an unloaded gun in a suitcase in the trunk of the car. By carrying a gun, he was officially on duty. Barr called the action “a sham arrangement” designed to avoid paying taxes on the rides, and undoubtedly it was. Sessions says he was only following the advice of the FBI’s legal counsel. Maneuvering for a tax loophole might be enough to cost Sessions his straight-arrow reputation, but it is hardly scandalous enough to cost him his job.

Many of the other charges involved Alice’s role as official wife. For instance, news reports said that FBI personnel objected to Sessions’ giving Alice a badge granting her access to the high-security area within FBI headquarters where he had his office. It did not seem unreasonable to Sessions or his wife that she be allowed to visit her husband at work. Another charge was that Sessions allowed Alice to travel with him on FBI planes to 111 locations without compensating the Bureau for her travel. Sessions says that he only allowed Alice to go with him if there was space available on the airplane, and that all of her trips were approved by the Bureau’s legal counsel. He acknowledges that he and Alice mixed business and pleasure on out-of-town trips—he went to San Francisco, where their daughter lives, eleven times and once stopped in Fort Smith, Arkansas, on his father’s birthday—but he insists he did nothing illegal or unethical. “There are only a few officials in the government who are never outside of security,” said Sessions. “I can’t separate personal from business time.”

There was no way to ferret out the truth, of course, and as is always the case in Washington, the accusations drew more headlines than the explanations. By the time the government’s reports were released, unnamed agents were telling reporters that Sessions was nothing more than an “empty suit” and referring to him (because of his settlement with minority plaintiffs) as “Director Concessions.” The ancient ritual of smaller sharks’ gobbling up the bleeding big shark was well in progress.

Alice saw the pattern long before Bill did. Last October I got the first of several telephone calls from Alice, whom I had known briefly in San Antonio. “Bill’s in trouble,” she whispered. “There’s a coup under way in his office, and he won’t do anything about it. He’s being stabbed in the back. He’s incredibly naive.” It’s not every day that the wife of the FBI director calls to tell you someone is dropping a dime on her husband. Either she’s crazy, I thought, or the entire government is corrupt. The conversation gave me the willies. “I can’t talk now,” she told me. “I’ll call you later from a safer telephone.”

Over the course of the next few months, she called back several times, telling me in advance what I would later read in the newspapers. In October Sessions met with Barr and told him that the FBI would conduct its own investigation of Iraqgate. Relations between Barr and Sessions had never been good, and published reports offered two reasons why: First, Barr thought Sessions hadn’t been a strong enough supporter of the Bush administration crime bill, and second, Barr was an ally of Floyd Clarke’s, Sessions’ contentious deputy. “Floyd Clarke is orchestrating Bill’s demise,” Alice said. “Barr is listening to Floyd, not to Bill.”

In December Alice telephoned again and said that Clarke was now out to get Sarah Munford, a special assistant to Sessions. “Bill still doesn’t see what’s going on,” she said wearily. In early January Munford, who had worked for Sessions since 1980, was fired by the Department of Justice. “They fired me so they could get to him,” Munford told me. “The Bureau is a closed society. The old guard wanted a director from within.” Three months after Alice’s first call, the Justice Department issued its report against Sessions. “I told you,” she said when we next talked by phone. “I think even Bill is beginning to get it.”

By the time I visited Alice at her home in March, it was obvious that even though she and Bill Sessions publicly defend one another, the quarrel within the Bureau has driven a wedge between them. “Alice has always been a free spirit,” Bill told me. “I’ve never tried to control her, and I never will.” He sees her as a loose cannon; she sees him as naive.

“The whole investigation has been slightly to the right of the Star Chamber,” said Alice, leading me upstairs for a tour of the house. “Here’s Bill’s room,” she said. The remarkable thing about the bedroom of the director of the FBI was not the security features—not the motion detectors, not the safety locks—but how neat it was. The four corners of his bedspread were crisply tucked in. On the nightstand was exactly what you would expect an FBI director to read: Tom Clancy’s The Hunt for Red October. In one corner was a set of barbells. Standing in the room, I remembered that Bill’s father, a minister in the Disciples of Christ Church, had written the handbook for the Boy Scouts’ God and Country award. Perhaps that is Bill’s basic problem: In Washington, there is such a thing as being too much of a straight arrow, and Bill Sessions is—in his heart—a Boy Scout.

Alice’s seventeen-year-old cat, Julia, followed her across the hall. “This is my room,” she said, standing in the doorway of a room that was the exact opposite of her husband’s. Boxes of newspaper articles sat on the floor. Clothes had been tossed over chairs. The bed was unmade. All four walls were decorated with pictures and paintings of angels. “I collect them,” Alice told me. Perhaps they have helped her deal with the tragedies in her life. Alice’s father, who was also a minister, was killed in a car accident when she was only seventeen. In 1963 Bill and Alice had a son, Jonathan, who was born with a heart defect. He lived only three months. Years ago Alice talked to me about the death of her son. “Bill and I pulled together during the crisis,” she said, “but we did our grieving apart.” They appear to be following the same course in the current crisis with the FBI.

“Before Bill accepted the job as FBI director, ” said Alice, as tears streamed down her face, “he asked me if I would be willing to travel with him—to go everywhere with him and talk to the families of agents, to serve alongside him in an official capacity. I did what he asked me to do. Now I’ve got to watch his backside.”

Alice Sessions is not the only person who thinks her husband’s backside needs watching. In late March Curt Gentry, who has studied the FBI for eighteen years and is the author of J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets, sent Sessions a confidential six-page memo. Gentry explained why he believes career professionals within the FBI—the men he calls the Hooverites—have resisted four of its directors.

Gentry wrote Sessions that within hours after President Nixon nominated the first post-Hoover director, L. Patrick Gray, in May 1972, top officials of the Bureau began plotting his demise. “They lied to Gray, saying, for example, that there were no secret files,” Gentry wrote. “They hid things from him, first and foremost the vast amount of corruption in the Bureau’s administrative division. They spied on him, compiling daily reports on his activities, remarks and contacts, reports allegedly so detailed that they had to have come from taps, bugs and/or his personal security squad.” Gray resigned less than a year later, a casualty of the Watergate investigation (he admitted to destroying the contents of E. Howard Hunt’s safe). But Gentry maintained that Gray would have been forced out anyway by his enemies. “They were gunning for him and they got him,” he wrote.

Next came William Ruckelshaus, a former deputy attorney general also nominated by Nixon. Gentry told Sessions that when Ruckelshaus arrived for his first day at work, he discovered that the acting associate director, all the assistant directors, and all but one of the agents in charge of field offices had begged the president to choose Gray’s successor from within the FBI. Ruckelshaus had no law enforcement background and knew nothing of the Hoover traditions, Gentry said. He lasted only seventy days.

In June 1973 Nixon chose Clarence Kelley, a retired agent with 21 years of Bureau experience who was then serving as the chief of police in Kansas City, Missouri. Shortly after Kelley took over, the first solid information about illegal acts during Hoover’s tenure was made public. But long before the extent of Hoover-era theft, kickbacks, and fraud was fully understood, Kelley made the mistake of accepting small perks, including new valances for his apartment and two TV sets for his use there. Three years later, when the Department of Justice investigated abuses within the FBI, Kelley was forced to pay back the cost of the valances and return the TVs. Gentry’s point was that the FBI’s tactics (keeping files on Kelley’s activities while allowing or possibly even encouraging him to make mistakes) were exactly those used to set up Sessions for the Justice Department probe.

When Kelley retired in 1978, President Carter appointed William Webster, a federal judge brimming with integrity, to replace him. “Judge Webster had been forewarned of the insular nature of the Bureau and its attitude toward ‘outsiders,’ ” Gentry said, “and he restructured the high command, appointing not one associate director but three executive associate directors, none of whom were ‘Hooverites.’ ” Webster surrounded himself with agents who were younger and less resistant to change, people he could trust. The moves were naturally unpopular with those who had been replaced. According to Gentry, when Webster was tapped by President Reagan in 1987 to become the director of the CIA, the Hooverites openly vowed, “Never another judge.”

But another judge is exactly what they got in Sessions. Near the end of his memo, Gentry listed the mistakes Sessions had made since taking office: listening to the wrong people, not realizing he would always be the outsider within the organization, and most of all, failing to recognize that he was dealing with a “palace revolt, the attempt of a small cabal, numbering probably no more than a half dozen senior officials, to recapture control of the Bureau. ”

It is difficult to gauge the accuracy of Gentry’s perceptions. The FBI is like a hall of mirrors; it is impossible for outside observers to tell what is true and false, who is running it and who isn’t. Even if Gentry’s charges are true, however, so much heat has been generated around Sessions that he probably can’t survive as FBI director. All of his allies—Democrats on Capitol Hill, big-name defense lawyers such as F. Lee Bailey, and civil rights activists such as Coretta Scott King—are outside the Bureau. His enemies are inside. “The dirtiest legal engine in law enforcement is a bootstrap,” Bailey told me. “The Hooverites in the Bureau used a bootstrap on Sessions. First they lied about him; now they say he has to be thrown out because they lied about him. That’s the worst bootstrap you can do.”

On the fourth day of the standoff in Waco between David Koresh and the FBI, Sessions sat in his Washington office, looking a little besieged himself. His desk was clear of paper. The television was tuned to CNN, but the sound was muted. The look on his face was grim; he had the demeanor of a condemned man. “I am not naive about what’s going on around here,” he said. “This has been hard for me personally, but I am sticking with it because the FBI should not be politicized. Nor should it be run by a small group from within who has its own agenda. ”

All around him, members of the in-house mutiny sat in their offices behind closed doors. Across the street, the Justice Department awaited the arrival of Janet Reno. “I believe the president will decide I am not guilty of unethical conduct,” said Sessions. “The arrows to the problems here point down, not up. But if he decides to replace me, I’ll respect his judgment.” In the meantime, said Sessions, he and Alice will soldier on. A few hours later they made a grand entrance at the National Museum of Women in the Arts. Bill, the highest ranking government official in the room, looked bright and cheerful, happy to be plucked from the rebellion and set down in the infinitely more glittering sphere of art and culture. He pumped hands and concentrated intently on the small talk that buzzed in the room. Alice wore a pink dress that she had made herself. She too seemed freer, more graceful, as she moved through the crowd.

“Isn’t this fascinating?” Sessions asked, peering at one painting. “It’s a Japanese painting, but it’s done with Chinese ink.” But the small group of art patrons around him wanted only to talk about the standoff in Waco.

“What’s the latest?” one woman asked.

“Well, there are still forty-seven women, forty-three men, and twenty children in the compound,” Sessions replied. “Plus thirteen puppies.”

“I hear Koresh won’t come out until he hears something direct from God,” said the woman, still desperate for inside information.

“That’s right,” said the director of the FBI. Then he offered a glimpse of what she had been waiting for—only she never knew it.

“Maybe,” said Bill Sessions, “I should have him call Alice.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- San Antonio