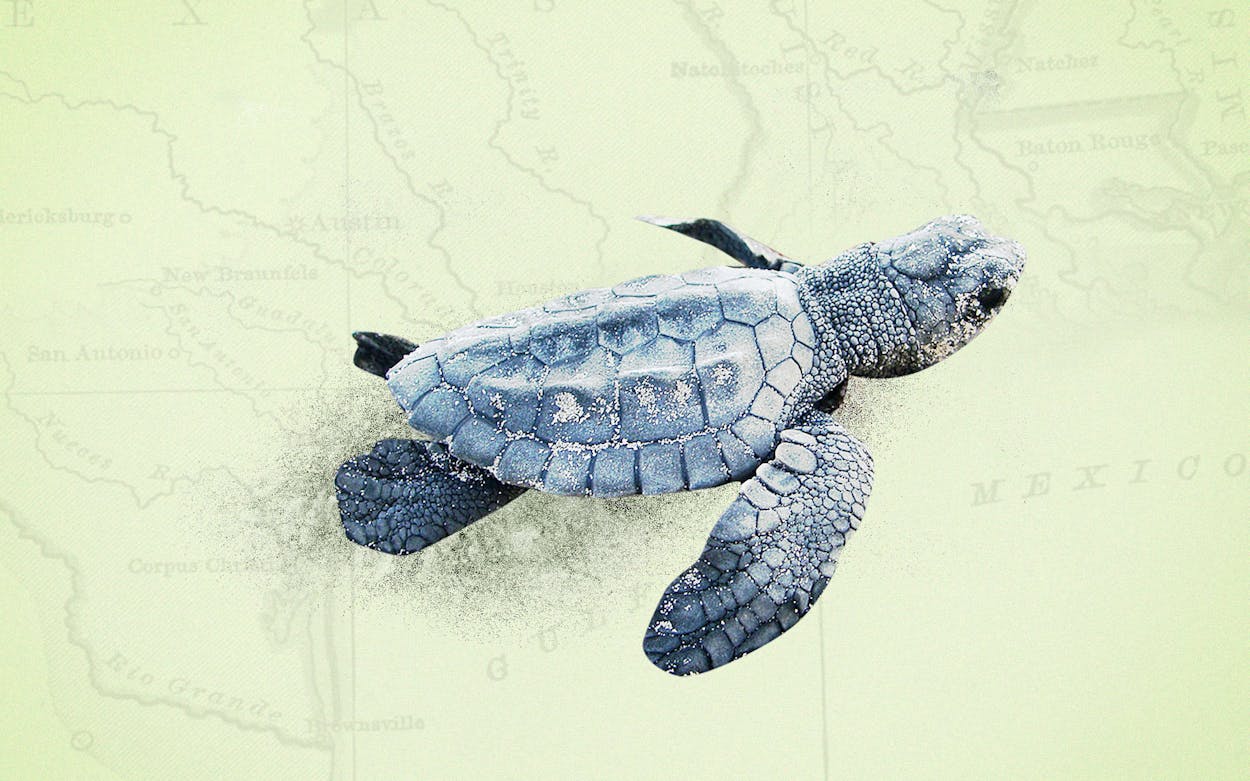

The Kemp’s ridley sea turtles begin arriving at Padre Island National Seashore in April, waves breaking against their olive-colored shells, salt spraying from their nostrils as they haul themselves up the sandy beach to nest. Every year, volunteers and park staff led by Dr. Donna Shaver—head of the National Park Service’s (NPS) Division of Sea Turtle Science and Recovery—are waiting for them. Both parties fall into a well-established rhythm: dozens of female turtles, in mass nesting events known as “arribadas,” or arrivals, work together to dig deep pits in the beach with their flippers. Then they deposit their eggs—often more than one hundred per female—and return to the sea. (The turtles may return to lay eggs one or two more times between April and August.) After each group of turtles has departed, the humans sweep in, moving the eggs to protected areas and incubators, carefully raising the next generation for release back into the Gulf of Mexico.

The Kemp’s ridley is the smallest (about two feet across) and most critically endangered sea turtle in the world, its numbers devastated by more than a half-century of individuals getting perilously tangled in fishing nets, lobster traps, and dredges. The species is also threatened by foragers who collect the eggs, kill the adults for their meat and shells, and disturb the beaches where the animals nest. More than 90 percent of Kemp’s ridley turtles nest in Mexico, with most returning to one beach near Rancho Nuevo, about two hundred miles south of Brownsville. In Mexico, the eggs are prized for food and also because some consider them an aphrodisiac.

Shaver’s program is a crucial partner in a forty-year international conservation effort meant to help the turtles recover. The one-of-a-kind program funds scientific research and knits together a constellation of private citizens, universities, and state and federal agencies; Shaver has garnered international acclaim as a leader in the field. The Kemp’s ridley is now a rare conservation success story: the number of Kemp’s nests found in Texas rebounded from just 6 in 1996 to 353 in 2017, and North Padre Island is their single biggest nesting site in the U.S., with smaller ones found in the Florida Panhandle and nearby Alabama.

Despite these impressive results, in a report published in June, regional NPS officials—none of whom appear to have worked in Texas—pushed to cut funding from the program. They also recommended a sharp decrease in the number of beach patrols to find turtle nests, fewer relocations of turtle eggs, a rollback of the hugely popular hatchling releases, and a limit on research or conservation activities conducted outside the park. Since the report’s publication, NPS officials have stripped away thousands of dollars of grant money from the program and forbidden Shaver from speaking to the media—including to Texas Monthly for this story.

In response, lawyers with the Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER), a Maryland-based nonprofit group that represents whistleblowers, filed a 28-page administrative complaint on Shaver’s behalf, alleging that the NPS’ recommendations, if carried through, are in violation of the federal Endangered Species Act—and that the report “suffers from a lack of integrity, accuracy, completeness, and reliability.” “We view this as an attempt to roll Dr. Shaver’s program back in and eliminate its programmatic identity,” says Jeff Ruch, PEER’s Pacific field director.

The Kemp’s ridley sea turtle spent much of its history as an enigma. Found primarily in the western Gulf of Mexico, its nesting habits were a mystery to scientists: some speculated that it was a hybrid between green and loggerhead turtles, not a distinct species. But in the sixties, a researcher turned up amateur footage shot at Rancho Nuevo, Mexico, in 1947. While most sea turtles nest individually under cover of darkness, the grainy film—shot by architect Andres Herrera—showed an estimated 40,000 Kemp’s ridleys nesting on the shore in broad daylight. It also recorded crowds of local residents harvesting both eggs and mothers. Researchers later estimated that more than 90 percent of the eggs in the film vanished the day they were laid.

According to Christopher Marshall, director of the Gulf Center for Sea Turtle Research at Texas A&M University–Galveston, the combination of decades of overharvesting and the expansion of commercial shrimping—which often drowned turtles in nets—devastated the Kemp’s ridley. Despite conservation efforts by the Mexican government in the sixties and a formal listing under the Endangered Species Act in 1973, turtle numbers continued to plummet. By 1976, fewer than a thousand were left. Finally, a coalition of Mexican and American researchers decided to try to build a second nesting site at Padre Island—the world’s longest undeveloped barrier island—to boost the population size and serve as insurance against any disaster that might strike Rancho Nuevo. The plan gambled on a then-unproven theory, Marshall says: that baby sea turtles imprinted on the beaches where they were born, with each female eventually returning, at about age fifteen, to lay eggs in that same spot.

From 1978 to 1988, thousands of eggs were transferred from Rancho Nuevo to Padre Island. Conservationists—including Shaver, who joined the park in 1981 and was leading the sea turtle program by 1986—incubated eggs, gathered hatchlings, and raised them at facilities in Galveston for the first year of their lives. (In the wild, 90 percent of baby turtles die before their second birthday.) Then workers released tagged yearlings on the beach at Padre Island and crossed their fingers. In 1996, turtles that had been tagged in the early eighties began returning to the island to nest.

Despite occasional setbacks, says Tom Shearer, a retired sea turtle conservation worker with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the program has been a resounding success: a network of volunteers, staff, and partners patrol local beaches, track down and relocate nests, rescue and rehabilitate injured turtles, and participate in popular hatchling releases. More than 15,000 visitors flock to the park annually to watch baby turtles crawl into the ocean—making the animals a vital part of the region’s tourism economy. “Back in 2000, we had nothing. Very few sea turtle nests,” Shearer says. “Now we’re up to 250 in Texas, and that’s mostly due to the work of people like Donna Shaver.”

While the report offered some praise for Shaver’s work, it took aim at the sea turtle program’s budget, calling it “disproportionately high compared … to the percentage of the turtle population being addressed,” and warning of possible budget shortfalls. The reviewers recommended limiting scientific research to the boundaries of the park and stripping the program of special project funding. In response to the report’s recommendations, Ruch says, regional NPS staff canceled two federal grants Shaver had won—a total of $300,000—for research on green sea turtles (a species more numerous than Kemp’s ridley turtles, but still classified as endangered), and forbade her from applying for more. (In a statement, the park insists that the program’s base funding is not being cut. Park superintendent Eric Brunnemann did not respond to an interview request from Texas Monthly.)

Critics describe the NPS’s actions as indicative of deeper institutional problems. A dearth of oversight over the past decade, Ruch says, has led to the formation of administrative fiefdoms, such as the one led by Michael Reynolds, who signed off on the review. Reynolds is director of three separate regions and more than eighty parks, spanning a swath of states from Texas to California and Wyoming. The NPS still lacks a director; the Trump administration has been in no hurry to appoint one, and its most recent acting director abruptly retired this month. The National Park Service has long been stretched thin financially, and perhaps never more so than under President Trump: his latest budget proposal called for the agency to lose 17 percent of its funding and eliminate nearly one thousand jobs. In such an environment, employees engaged in long-term work to sustain wildlife in places such as Yellowstone and the Grand Canyon are increasingly facing institutional blowback, and—as in Shaver’s case—may be pressured to focus less on scientific research and more on basic operations.

“One of the points of the review is that they don’t think the research is valuable, so it should be de-emphasized or done away with,” Ruch says. “And that to me is sort of a dangerous trend that bodes ill for the long-term intellectual health of the National Park Service,” particularly when it comes to supporting important scientific and conservation work.

Researchers outside the NPS—including some interviewed by the reviewers, such as Marshall of Texas A&M—are also concerned that the review doesn’t seem to reflect the facts on the ground. One of the review’s recommendations involves simply leaving the sea turtle nests on the beach, where they are vulnerable to high tides and predators such as coyotes and raccoons. In a healthy population, Marshall explains, such losses are natural—but they’re a serious problem when you’re trying to rebuild a small population.

“People on the East Coast feel that [removing eggs for incubation] is an extreme conservation measure,” Marshall says. “I think they’re right, it is pretty extreme—if you can avoid it, you would like to, but we’re in an extreme situation here. When you’re putting eggs in an incubator, you’ve got around 90 percent hatching success, versus 60 percent on the beach. We have to save every egg that we can.”

The other problem with leaving turtle nests on the beach? Beach driving, which is legal in Texas, can wreak havoc on nests. The report suggests simply closing the beach during the nesting season—which lasts from April until August—or charging for more expensive permits for beach driving. Both are political nonstarters, Shearer says, and would lead to a serious fight with local communities and the state’s General Land Office. “There were a lot of things in there that they didn’t seem to have researched very well,” Shearer says. “And some comments that just—to me—didn’t reflect someone who understood the Texas coast.”

Since PEER raised its legal objection to the review on July 16, the NPS has sixty days to decide what to do. If the agency rejects the complaint, PEER plans to appeal, which will require the NPS to convene an independent panel to review the dispute. The crucial point, Ruch says, is that implementing any serious changes to the Kemp’s ridley management program without inviting and considering public commentary is a violation of the law—and as yet, the NPS has offered no such transparency.

In a statement delivered after PEER’s complaint was made public, the NPS acknowledged that some of the review’s recommendations required “careful study and public feedback” before they could be implemented. “Indeed, no changes to the park’s nest management program have been implemented,” the statement went on. “Doing so would require further review as mandated by the Endangered Species Act.” NPS leaders declined our requests for interviews.

Initial reactions on Padre Island suggest that any public forum is going to result in the park service getting an earful. Nick Meyer, president of the Breakaway Tackle store in Corpus Christi, has been fishing the Padre Island National Seashore since 1995. He’d previously butted heads with Shaver over a speed limit for beach drivers. But now, Meyer is rallying support against the suggestions in the review—particularly the suggestion around limiting beach access. “My business is based on shore fishing,” he told Texas Monthly. “If you close that beach for three or four months a year, that’s gone. It would take a third of my business away … We have fought the National Park Service before, and we’ve got lawyers who give us their services to make sure we put up the best fight we can.”

The suggestion to decrease the public hatchling releases—an adorable spectacle of tiny, big-eyed black hatchlings flailing down the sand toward the water—hasn’t gone over well either. The report recommends cutting the public releases from their current 25 a year to 1 per year. The hatchling releases are a vital part of the local tourism industry and draw in visitors from all over Texas, Meyer says—visitors who book hotel rooms, dine in local restaurants, and spend money at other nearby attractions, such as the Texas State Aquarium.

“They brought three people in from out of state, did this report, didn’t even speak to Donna [Shaver], certainly never spoke to any of the fishermen, and then slung that report out,” Meyer says. “It was wrong and it should be withdrawn.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Critters