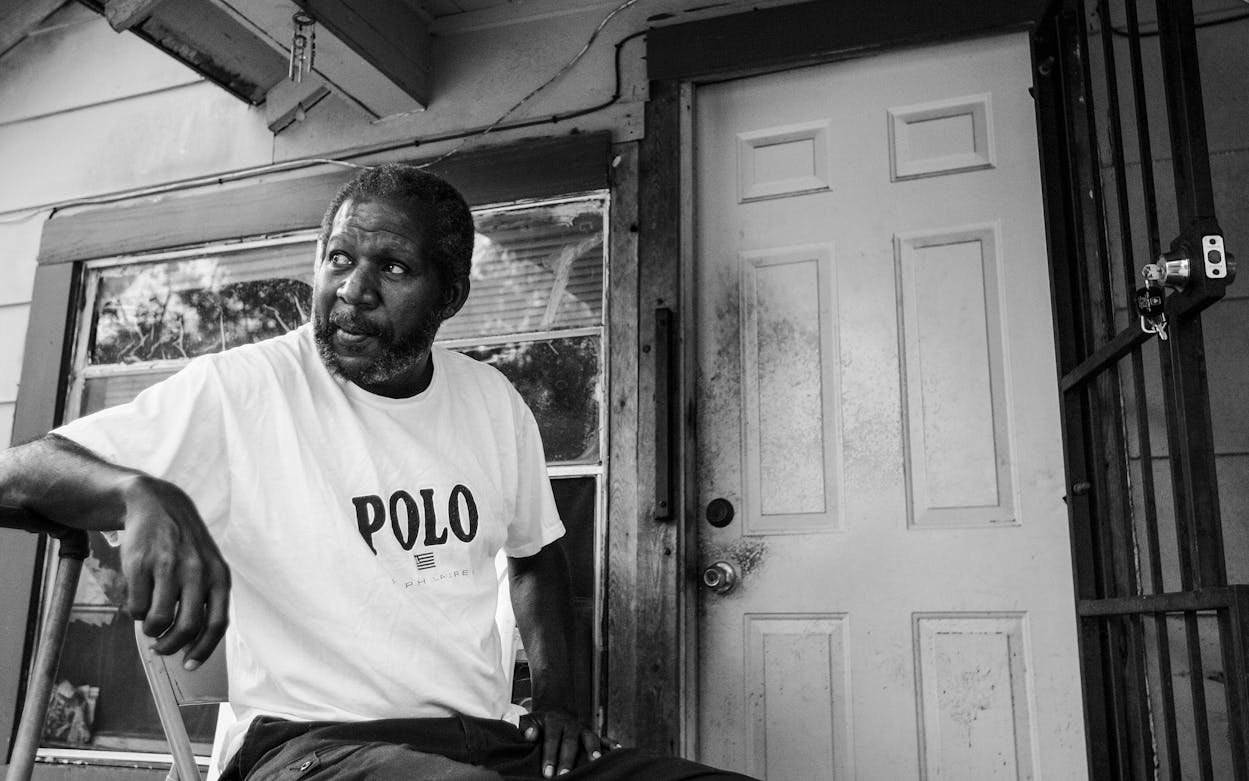

Clarence Brandley, who escaped death in the Texas execution chamber, died from pneumonia on September 2, 2018, in his home near Conroe. He was 66. Brandley was one of the first men to be released alive from Texas’s death row, back in 1990. Exonerations of the wrongly convicted occur regularly now, but 1990 was a very different time. “This was a rare event,” says Jim McCloskey, who was instrumental in Brandley’s release. “An innocent man on death row was a huge story.”

Brandley, a black man, was a quiet and reserved janitor supervisor at Conroe High School in 1980, when a sixteen-year-old girl was raped and strangled at the school during a volleyball game. Though no physical evidence linked Brandley to the crime (and he passed a polygraph test), the Vietnam War veteran was put on trial primarily on the word of four white janitors, who all reconstructed a version of events that positioned Brandley with the murdered girl at the time of her death. While the other janitors gave alibis for each other, Brandley didn’t have one.

He was first tried before an all-white jury in 1980, but they couldn’t reach a verdict, and the judge declared a mistrial. He was tried again the next year, again in front of an all-white jury—and this time he was convicted. After his appeals ran out, Brandley was assigned an execution date of March 26, 1987.

He would almost certainly have been executed if not for the intercession of Jim McCloskey, a man from New Jersey who had founded an organization in Princeton called Centurion Ministries, which worked to free the wrongly convicted. Centurion had helped exonerate three men so far, but none from death row.

McCloskey came to Texas in February 1987 and, working with Brandley’s appellate lawyers, convinced one of the janitors, John Henry Sessum, to tell the truth about what he saw that day: it was another man, Sessum said, who had killed the girl, not Brandley. A second witness followed suit, and with the new evidence, the lawyers were able to get a judge to stay the execution, which at that point was only five days away. McCloskey also convinced Sessum to tell his story on 60 Minutes, giving the case credibility and taking it to a national audience. (Texas Monthly did a story on Brandley in September 1987, when he was still on death row.)

After an evidentiary hearing, a judge ordered a new trial, saying that in his thirty-year career, “no case has presented a more shocking scenario of the effects of racial prejudice, perjured testimony, witness intimidation [and] an investigation the outcome of which was predetermined.” Brandley was freed on January 23, 1990, walking out of the Ellis Unit (near Huntsville) accompanied by McCloskey and attorney Mike DeGeurin.

Eventually the D.A.’s office dropped charges against Brandley, even as prosecutors insisted he was still guilty. Brandley was never granted a pardon and so was never compensated for his ten years on death row. He became a Baptist minister and set up his own storefront church in Houston but eventually gave it up and moved back to Montgomery County, where he lived with his girlfriend in a rural area near Conroe.

“He never got an apology, never got any satisfaction from anyone,” says McCloskey, a veteran of 62 exonerations who still remembers walking out of the Ellis Unit with Brandley as the most gratifying moment of his life. “Clarence Brandley was one of the bravest men I’ve ever known. Even when he had that execution date five days away, he was sitting there so calm and strong. He was religious, no question. He knew he was an innocent man. I can’t say he believed we’d succeed, all he’d say was he was deeply appreciative of what we were doing. ‘Keep it up,’ he’d say. ‘Maybe something will break, and if it doesn’t, I know you’ve done your best.’ He knew he’d go to his maker with a clear conscience.”

- More About:

- Death Row