In 2007, when I first met Jeff Pike, he had just finished an eleven-mile bicycle ride. He was wearing shorts, a T-shirt, and tennis shoes. We were at his two-story home that he had built on some secluded property five miles outside of Conroe, north of Houston. He was a good-looking guy, then 51 years old, and he wore his salt-and-pepper hair in a crew cut. As he handed me a bottled water, he gave me the most cheerful of grins. “Not what you expected, huh?” he asked.

Not exactly. At the time, I was told by law enforcement officers that Pike was Texas’s Tony Soprano, a ruthless criminal who led the Bandidos with an iron fist. One undercover agent with the Department of Public Safety warned me to be very careful around the Bandidos’ boss. “The last thing you want to do is get on his bad side,” he said.

Yet Pike simply shrugged as I asked him about the various allegations that had been thrown his way—including a recent report that he even had ordered the executions of some wayward Bandidos in Canada who hadn’t been following club rules. “It’s ridiculous,” he said.

Pike liked to describe himself as an ordinary guy: a divorced father whose two children attended the University of Texas. He said he got up early in the mornings, made the bed, walked the dogs, spent time restoring custom cars in a fabrication shop on his property, rode his bicycle to stay in shape, took his new girlfriend (a certified public accountant) to the movies, and occasionally participated in weekend “runs” (motorcycle trips) with his fellow Bandidos.

“Why can’t the feds just accept the fact that we are a bunch of bikers who love to get together and have some fun?” he said, tossing his empty bottled water into a trash can. “Why don’t they start chasing real criminals, like those kids in street gangs who scare the shit even out of me, instead of following us everywhere we go, tapping our phones, and trying to destroy us with a bunch of made-up charges?”

I have to admit, I enjoyed the heck out of him. When I later met him for dinner at Kirby’s, the upscale steak restaurant in the Woodlands, he roared up on a gleaming Harley Davidson and strolled into the restaurant wearing his “colors” (a dark, denim Bandidos vest). I felt like I was dining with a celebrity. People slowed past our table to get a good look at him. We talked about noncriminal matters—sports and politics—and after eating his steak and having one drink, he left at 9:30, telling me he had to get home because he liked going to bed by 10 p.m. “This man is a vicious killer?” I asked myself.

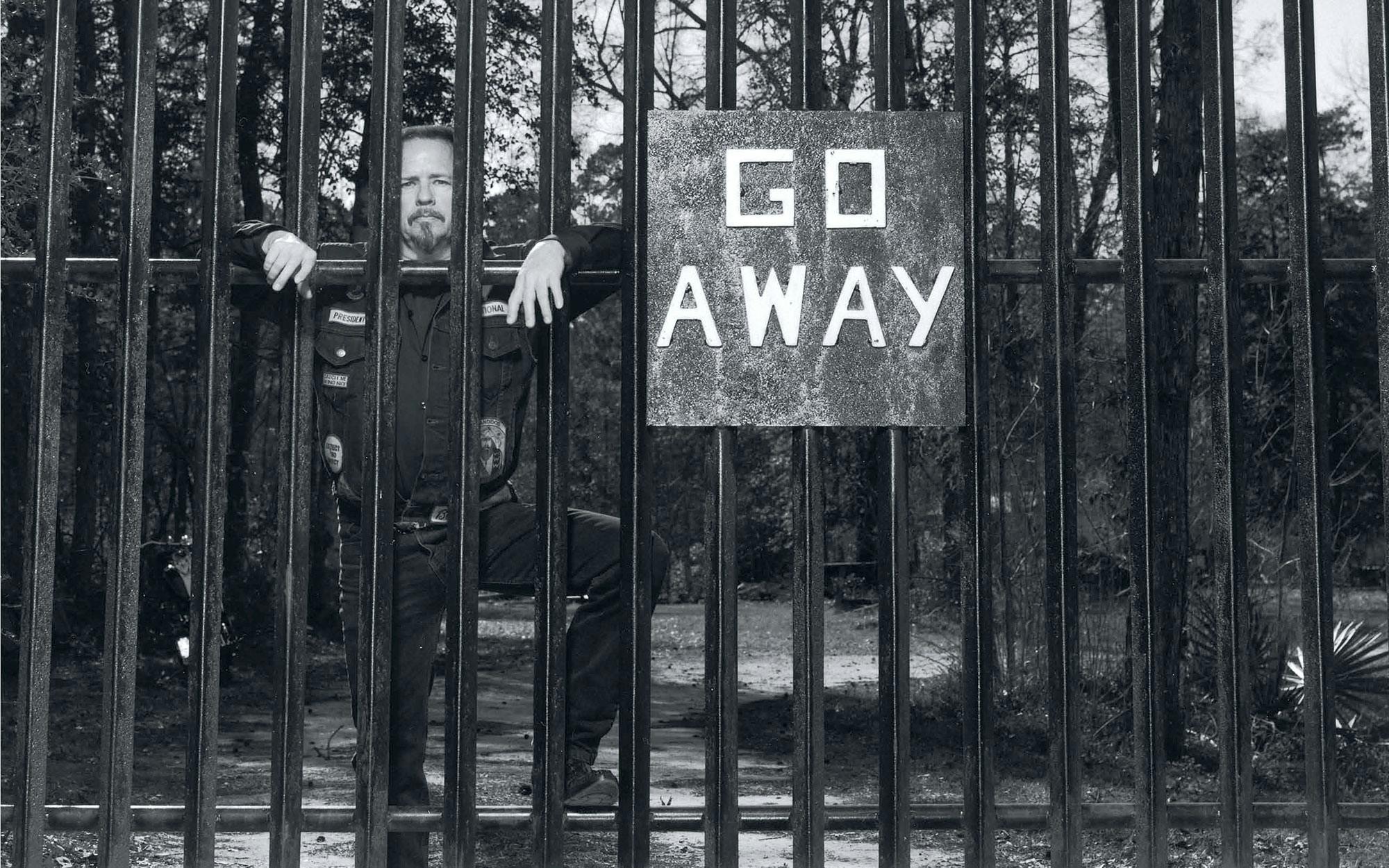

Over the next several years, I’d hear rumors that Pike was the subject of a federal investigation. But the stories were just that—nothing more than rumors. Pike seemed to be untouchable. Then, in January 2016, a couple of dozen federal officers drove up to Pike’s wrought-iron front gate (which had a Christmas wreath attached to it), stared at the security cameras mounted in trees, and ordered Pike through a loudspeaker to let them in. At the same time, other agents and officers arrived at the San Antonio home of the Bandidos’ national vice president, Jorge Portillo.

Pike and Portillo were arrested on racketeering and conspiracy charges. According to prosecutors from the U.S. attorney general’s office, Pike had issued secret orders to Portillo about assaults and murders he wanted carried out in order to maintain control of the club’s territory and profits, and Portillo, in turn, had ordered certain Bandidos to commit those crimes. In particular, the prosecutors said, Pike had ordered hits on bikers from other motorcycle clubs, including an Austin man who was trying to start a Texas chapter of the California-based Hells Angels motorcycle club, one of the Bandidos’ chief rivals. Pike also allegedly had authorized a war on the Cossacks, a smaller Texas-based motorcycle club that had dared to challenge the Bandidos’ reign. That war, of course, had culminated in the now-infamous May 17, 2015, gun battle involving Bandidos and Cossacks at a Twin Peaks restaurant in Waco. When the shooting finally stopped, nine bikers had been killed, seven of them Cossacks.

Dick DeGuerin, the well-known Houston defense attorney who represented Pike, dismissed the indictment as rubbish, declaring that prosecutors were trying to make Pike responsible for the behavior of some renegade Bandidos. Yes, DeGuerin acknowledged, there were Bandidos who had committed crimes while Pike was president, but he had no idea what they were doing. And he certainly hadn’t instructed anyone to break the law. “The Bandidos are not a criminal enterprise,” DeGuerin said. “They are about fellowship. Their primary purpose is that they love motorcycles and the freedom that motorcycles give a person.”

In the same vein, San Antonio attorney Mark Stevens portrayed his client Portillo as a family man who owned a small company that installed heating and air-conditioning units and who liked riding with the Bandidos on weekends to relax.

Nevertheless, prosecutors were confident they had the evidence to bring down Pike and Portillo. They not only had received a court order to tap Portillo’s cell phone, they also had persuaded eight Bandidos and former Bandidos to testify about the inner workings of the organization.

The trial began in late February in federal court in San Antonio. Every day, the jurors, whose names were kept secret, were bused to the courthouse from an unknown location, accompanied by armed guards. After they took their seats, they glanced at Pike, who’s now 62, and at Portillo, who’s 58. Pike always wore a nice dark suit, a white shirt, and a tie, and Portillo wore a dark shirt and a sports coat. At the defense table, the two Bandidos looked like harmless, aging businessmen meeting for lunch.

During my conversations with Pike, he often told me that he knew “the feds,” as he called FBI and DEA agents, were doing their best to put him behind bars. “I once had a cup of coffee with an FBI agent at a Denny’s and he said, ‘You know, Jeff, we’re looking at you.’ ”

“So why be president?” I asked him. “Why be a Bandido at all?”

He gave me a look, as if he sort of pitied me. “If you have to ask, then you’ll never understand,” he said.

The Bandidos were formed in 1966 by a former Vietnam veteran named Don Chambers, who was then 36 years old and working on the ship docks in Houston. Chambers had been a member of other Houston-area motorcycle clubs, but they had bored him. He told his friends that he was naming his club the Bandidos in honor of the Mexican bandits who refused to live by anyone’s rules but their own, and he made it clear that this was not going to be a club for anyone who belonged to what he called “polite society.”

Chambers recruited his first Bandidos not only out of Houston but out of the biker bars in Corpus Christi, Galveston, and San Antonio. Many of them were also restless young Vietnam veterans, and they loved the Bandidos. As I wrote in an April 2007 article, “The Gang’s All Here,” they had wild, unruly hair, scraggly beards, huge tattoos, and cigarettes sticking out of their mouths, and they went by such nicknames as Revolver, Pecker, Deadweight, Rawhide, Coonass, and Crankcase. One member was nicknamed Log Cabin because he loved drinking whiskey from a Log Cabin syrup bottle.

They quickly developed a reputation as Texas’s biggest badasses, self-proclaimed outlaws who loved the open road. They were arrested for dealing drugs, running prostitution rings, extorting money from the owners of roadhouses and strip joints—even operating illegal pit bull fights. They also ran roughshod over other biker clubs, telling them that they controlled Texas, going so far as to make the other clubs pay dues to ride the state’s highways. The Bandidos also made it clear to those clubs that only Bandidos had the right to wear a “Texas rocker”: a semicircular patch on the back of their vests that read “Texas.”

When Chambers went to prison in 1972—he was convicted of a double murder near El Paso for settling a score over a drug deal—he was replaced by his right-hand man, Ronnie Hodge, another former Houston dockworker who was the size of a grizzly bear. In 1988, Hodge and other Bandidos national officers were convicted in a federal trial for conspiring to bomb homes and automobiles belonging to members of the Banshees, an upstart Dallas motorcycle club. Hodge’s successor, Craig “Jaws” Johnston, was found guilty of conspiring to manufacture and sell as much as a thousand pounds of methamphetamine, and Johnston’s successor, George Weggers, went to prison on racketeering charges. In 2005, the Bandidos national officers picked Pike to be the club’s fifth president.

Pike grew up in California. He was an altar boy at a Catholic church until he realized he preferred hanging out at an arcade playing pinball. He came to Texas in 1973, when he was eighteen years old. (“I was told it was legal to drink beer in Texas at eighteen and I said, ‘I’m on my way.’ ”) He got a job in construction, bought a Harley in 1975, began hanging around some Bandidos, and was officially invited into the club in 1979. Pike told me, “When my best friend’s mother heard I had joined, she got real scared and said, ‘You’re not going to kill me, are you? I heard new Bandidos have to promise that they will be willing to kill their best friend’s mother.’ ”

Pike admitted that he did get into a few fights as a young Bandido. He once rode to Galveston with other Bandidos to beat up some rival bikers who were causing problems at a topless club that the Bandidos liked. In 1987 he paid an $800 fine after pleading guilty to a misdemeanor assault charge (he admitted stabbing a man who was arguing with him at a party), and in 1992 he received twenty months deferred adjudication after being charged with illegally wiring his house in order to steal electricity from the city of Houston.

But those were the only two crimes on his rap sheet. Compared to other unruly Bandidos, he was a clean-cut yuppie. Perhaps that’s why he was named president. Because he got along so well with polite society—one FBI agent would later say at a court hearing that he always found Pike to be “cordial” whenever they talked—the thinking was that he would be able to persuade the feds to stop snooping around.

Pike did instill some reforms. He demanded that his fellow Bandidos stop describing their girlfriends as “property.” He had some members kicked out for drug dealing and had other members kicked out for what he described as “bad conduct.” To avoid drawing attention to himself, he did away with the large “El Presidente” patch worn on the back of the national president’s vest and replaced it with a small patch over the front pocket that simply read “president.”

When Pike gave interviews to the press, he liked to say, “We are not your father’s Bandidos.” He described his members as men who steered clear of the law, worked good jobs, bought braces for their kids, and wore khakis and golf shirts when they weren’t riding their motorcycles. He always mentioned that he too was living a crime-free life. He had married his accountant girlfriend. They vacationed on cruise ships together and posted pictures on Facebook. At Christmas, he did toy runs with other Bandidos, delivering presents to needy children. “We are not a threat,” he once told me. “You leave us alone, and we’ll leave you alone.”

Under Pike, the Bandidos grew in size, becoming larger than the fabled Hells Angels. The group consisted of an estimated 2,000 members in sixteen states (about 600 in Texas alone) and another 1,400 members in Canada, Europe, and Australia. The feds, however, just chuckled at Pike’s talk about the club softening its tough-guy persona. They also suspected that Pike himself was up to some sort of no good. For one thing, he was extremely cautious about the people he allowed to get close to him. He seemed so anxious about undercover cops infiltrating the club that he had instilled a strict screening process requiring members who sponsored a new “prospect” to have known that person for at least five years.

The feds really got interested in Pike in 2006, when an Austin biker named Anthony Benesh III began displaying Hells Angels colors as he rode the streets. He was warned by Austin-based Bandidos to stop, but he ignored them. On a Saturday evening in March 2006, Benesh was shot in the head by a sniper’s rifle bullet as he was walking out of a restaurant with his girlfriend and his two sons. Surely, investigators said, a Bandido would not have carried out such a highly public hit on his own. Surely, Benesh’s murder had to have been sanctioned by the club’s boss.

But the investigation went nowhere. Then, in late 2013, word circulated through law enforcement circles that the Bandidos were going after the Cossacks, a younger Texas-based motorcycle club that, in the words of biker expert Donald Charles Davis (who blogs under the name the Aging Rebel), was “aiming to gain notoriety.” Some Cossacks had been seen wearing the “Texas rocker” on the back of their vests, which the Bandidos considered a deliberate provocation. To members of polite society, grown men feuding over a patch seems, well, comical. But in the biker world, being treated with respect is of paramount importance. And as far as the Bandidos were concerned, the Cossacks needed to be punished for their disrespect.

A number of clashes or confrontations between the two biker clubs soon broke out around the state. At a gas station in West Texas, about twenty Bandidos and their associates attacked a Cossack and took his vest. One Bandido beat the Cossack with a claw hammer, leaving deep gashes in his head. In Fort Worth, at least ten Bandidos stormed into a bar called Gator’s that was known as a Cossack hangout. The Bandidos were carrying clubs, large heavy flashlights, and at least one gun. A melee broke out and one biker, a member of a Cossack support club, was shot to death.

Agents from the DEA and FBI decided to make their move. They confronted Johnny “Downtown” Romo, a former national officer for the Bandidos who lived in San Antonio and was close to Portillo. They told Romo they were prepared to arrest him on drug trafficking charges, but they promised to drop the case if he would agree to wear a wire to his meetings with Portillo.

In the Bandido world, loyalty to the club is highly prized. (Some Bandidos have bumper stickers on their motorcycles that read “Shoot Informants Not Drugs” and “Snitches Are a Dying Breed.”) Members suspected of snitching are not only kicked out of the club—they are brutally beaten and their Bandidos tattoos are forcibly removed.

Incredibly, however, Romo decided to betray his fellow Bandidos. He put on the wire and agents listened in as Portillo told Romo, “We’re not going to f— around with them Cossacks, dude. It’s on. Our patch, our club, is at war with these f—ers.” During that same conversation, Portillo also said he planned to increase membership dues to help pay legal costs for Bandidos members who might end up in legal trouble for fighting the Cossacks. He then said that he had informed “the guy in Houston to turn his back from what I’m going to do.” Obviously, the feds believed, the guy in Houston was Pike. Portillo had informed Pike to turn his back so that Pike could claim ignorance of the plans to attack the Cossacks.

After the May 2015 Twin Peaks shoot-out, which was described in the Washington Post as “one of the worst eruptions of biker-gang violence in U.S. history,” I again interviewed Pike for a July 2015 story, “Gang Land.” He told me he knew nothing about what had taken place in Waco. He had been laid up in bed, he said, recovering from surgery. “Hell, no, I didn’t order any hit,” he said. “We don’t do shit like that. And we sure as hell wouldn’t do something like that in front of cops.”

At the time, what I didn’t know was that the feds had received a secret court order to wiretap the cell phones of Portillo and Justin Cole Forster, a national sergeant at arms in charge of enforcing the Bandidos’ rules and handling security at Bandidos gatherings and meetings. On top of that, the feds had begun putting the squeeze on a handful of Bandidos they had arrested for various crimes, offering them lighter sentences in return for their testimony about the way Pike and Portillo ran the club.

The stories eventually piled up. Portillo said those Bandidos who had cut deals acted as a buffer between Pike and the rest of the club, but Portillo definitely had let it be known that Pike was in charge. They said Portillo had told them that Pike had ordered the execution of Benesh, the Hells Angel in Austin, and that Pike had told Portillo to send Bandidos to intimidate and attack other rivals.

And there were rare occasions, they said, when they heard from Pike himself. Johnny “Downtown” Romo said that Pike had told him to deal with a recalcitrant chapter president of the Australian Bandidos. “I don’t care what you do,” Romo quoted Pike as saying. “Throw him in the ocean, do whatever the f— you gotta do.” Another Bandido, William “Big G” Ojemann, who was six feet three inches tall and weighed 420 pounds, said he had attended a meeting in 2011 at the Mason Jar restaurant in Houston in which Pike got angry at “Galveston John,” the Bandidos’ chapter president in Costa Rica, for openly disagreeing with him about an issue. Ojemann said as he rode with Pike back to his house, Pike was in a rage. “I remember him turning down the radio and saying he wanted Galveston John’s [the Costa Rica chapter president’s] ass,” Ojemann said. “He was pissed. He wanted Galveston John f—ed up.”

In truth, the feds had no direct evidence that Pike was involved in any crime, nor did they have him on a wiretap making incriminating statements. But under the federal racketeering statute (which has less strict hearsay rules than normal criminal cases), prosecutors from the U.S. attorney’s office were still able to make a case on Pike based almost entirely on the stories told by the Bandidos they had flipped.

At the trial, those Bandidos hesitantly made their way to the witness stand. They could barely look at Pike and Portillo. They knew the consequences they faced for their betrayal. One of them, in fact, testified that he had begged the federal prosecutors to place him in the witness protection program “because there’s no way I can live in San Antonio after this. What I did is unforgivable.” Asked what he did, he replied, “Snitching.”

Although Portillo did not testify in his defense, Pike gladly did. He said his goal as president had been to attract more mainstream and family-oriented members—“different, younger people; more settled, I guess you would say.”

He insisted he was unaware of any beatings or murders of rivals or of fellow Bandidos, and he was especially adamant that he didn’t sanction a “war” against the Cossacks. He said he went so far as to inform the Cossacks leaders that they could wear the Texas patch. “I like it when everybody gets along,” Pike said. “I don’t like drama.”

Pike held his ground during cross-examination, calmly answering questions from assistant U.S. attorney Eric Fuchs. The only moment when Pike almost lost his composure was when Fuchs asked him to define a snitch. Pike snidely replied that a snitch was “a witness who makes up stories to get himself out of trouble.”

In final arguments, DeGuerin told the jury that there was still no evidence connecting Pike to any assault or killing. Pike was a family man, said DeGuerin. He soon would be a grandfather. But Fuchs went on the attack. Under Pike and Portillo, he declared, the Bandidos were “the Mafia on two wheels.”

On Thursday, May 17, after two and a half months of testimony, the jurors came back with a verdict. Pike and Portillo, they said, were cold-blooded killers, guilty of all charges that had been levied against them. The judge said he would announce Pike’s and Portillo’s sentences later this fall, and then he gaveled the trial to a close. The two Bandidos remained stoic as they were handcuffed and led away.

DeGuerin, who rarely loses, seemed devastated by the jury’s decision. “I truly believe Jeff is innocent,” he told me. DeGuerin knows that under federal sentencing guidelines, Pike is most likely going to receive a life sentence without the possibility of parole. He’s never going to see the light of day again. “But here’s the thing about him,” DeGuerin said. “When we talked after the verdict, his biggest worry was about his wife Heather. They had stayed in his RV during the trial, and he was worried that she might have trouble driving it back to their home.”

There was a silence. “Think about that,” DeGuerin finally said. “Instead of worrying about his own future, he was worried about his wife’s safety. You have to admit that’s pretty remarkable.”

- More About:

- Crime

- The Woodlands