In the fall of 2017, seventeen-year-old India Landry was expelled from Windfern High School in Cy-Fair, outside of Houston. She’d been in trouble at the school that year, but not for her grades or disciplinary issues. Rather, she was in the principal’s office after being kicked out of English class five times already that semester for her refusal to stand during the pledge of allegiance. When the pledge came over the intercom that morning, she again stayed seated, while the principal and a school secretary stood. The principal asked her to stand, she told KHOU. “I said I wouldn’t, and she said, ‘Well, you’re kicked out of here,'” Landry told reporters.

Landry had refused to stand for the anthem for a year and a half, according to a New York Times story from last fall, before she was expelled. After the case received media attention, principal Martha Strother reversed course and allowed Landry to resume classes. The lawsuit Landry filed in response to her initial expulsion, though, remains in court, challenging the constitutionality of a Texas law that requires students to have written parental permission in order to decline to stand for the pledge of allegiance.

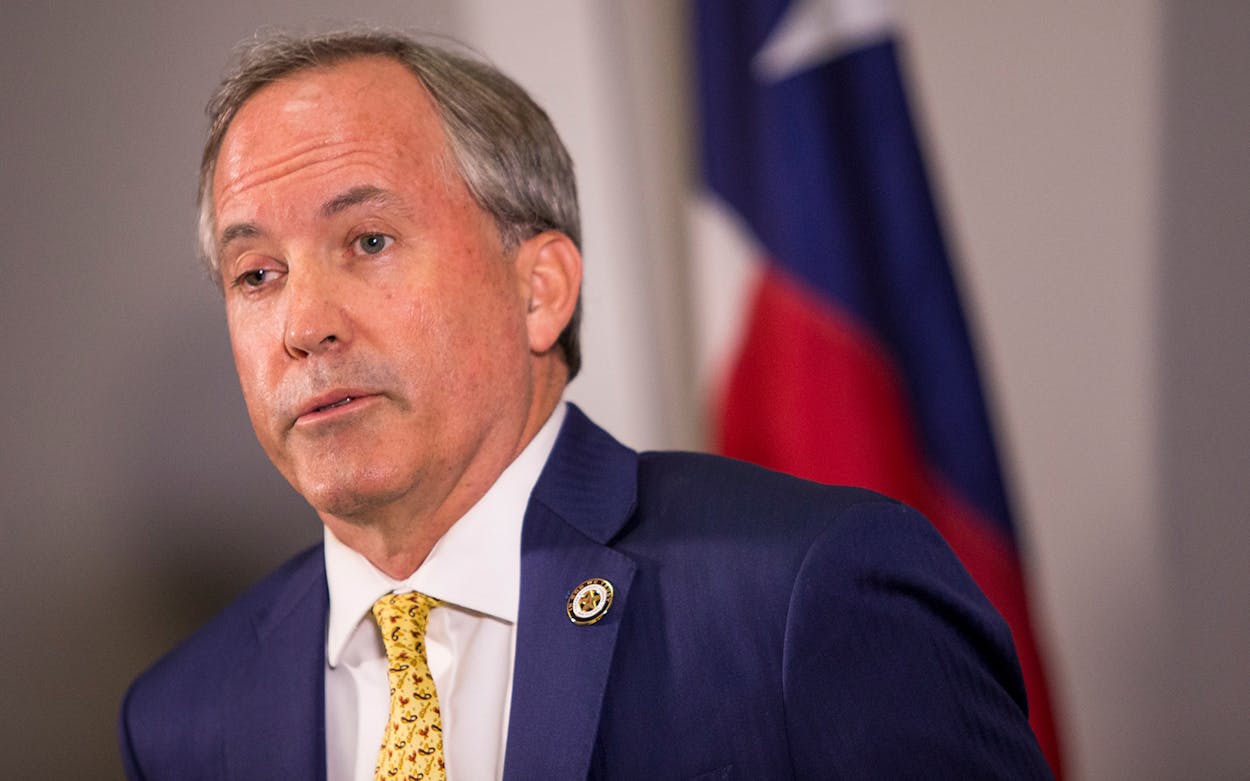

Texas law requires students to recite the pledge (under the statute, standing isn’t required) with the caveat that “On written request from a student’s parent or guardian, a school district or open-enrollment charter school shall excuse the student from reciting a pledge of allegiance.” This week, Attorney General Ken Paxton announced that he’d be using his office to attempt to ensure that section of the Texas Education Code remains in place amid the legal challenge.

The suit—and Paxton’s response—raise a few questions. Paxton’s motion to intervene argues that the state has an interest in ensuring that the daily recitation of the pledge of allegiance is included as part of the educational experience of every Texan, and states that the parental opt-out offers an appropriate remedy to families concerned that the forced recitation of the pledge goes against their values. Landry’s suit argues that students have free speech rights irrespective of their parents, and that those rights are violated by the statute in question.

The debate is made more fraught because of the current conversation around patriotism and the NFL. The question of whether kneeling during the national anthem disrespects the flag is one that’s been asked countless times since Colin Kaepernick began demonstrating against police brutality during the anthem at the start of the 2016 NFL season. The disagreements around that have been heated: Kaepernick is still out of the NFL, but he’s the current face of Nike; Donald Trump’s tweets and rants about kneeling NFL players have enflamed tensions around the country; the question has somehow become one of the standout differences between Beto O’Rourke and Ted Cruz in the Texas senate race—and the issues around the pledge clearly mirror those around the anthem.

The pledge of allegiance has been part of the education of American schoolchildren for more than a century—its author, Francis Bellamy, wrote that since penning the pledge in 1892, most American children have uttered his 23 words. (In 1954, President Eisenhower signed a bill adding two more words—”under God”—in the second half of the pledge).

Writing about his reasons for crafting the pledge, Bellamy referred the post-Civil War era in which it was written. “‘Allegiance’ was the great word of the Civil War period,” he wrote, and pledging allegiance to the Union flag instilled in the children who would recite it the notion that America was a single, unified country. “The flag stands for the Republic. And what does that vast thing, the Republic, mean? It is the concise political word for the Nation, the One Nation which the Civil War was fought to prove. To make that One Nation idea clearer, we must specify that it is indivisible, as Webster and Lincoln used to repeat in their great speeches.”

Many generations after the Civil War, we’re once again a deeply divided nation. The pledge was intended to instill a sense of pride, patriotism, and loyalty among American children, but it’s clear from Landry’s lawsuit that young people today are questioning whether the ideals of liberty and justice for all (which Bellamy chose over “liberty, equality, fraternity,” believing those to be “too many thousands of years off in realization”) are represented by the flag. The courts will decide whether continuing to mandate the recitation of the oath for those students honors the ideals of liberty and justice for all—but at the moment, we know where the Texas Attorney General’s office stands on the question.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Ken Paxton