While the most high profile POW from the Vietnam War may have been the late Republican Senator John McCain, there was another downed flyer and McCain cellmate for a time who has an equally extraordinary story of a military pilot turned captive turned lawmaker—Texas’s own Representative Sam Johnson, R-Plano.

Outside the public eye, Johnson and McCain were quite close and during their time in Congress tried to have breakfast together a least once a month. McCain was elected to the House in 1982 and the Senate in 1986. They had been cellmates for about 18 months—Johnson, an Air Force pilot who had flown in the Korean and Vietnam conflicts, was in the Hanoi Hilton for nearly seven years and McCain, a Navy flyer, for five and a half years. The 591 POWs held in Vietnam were released in early 1973.

After McCain died in August and was lying in state in the Capitol Rotunda, Johnson, who needs assistance getting around, usually a motorized scooter that he needs because of the injuries he sustained from his ejection when his plane went down, as well as from years of torture, was one of the first House members to arrive for the congressional ceremony. In an emotional moment, he rose from a wheelchair and approached his friend’s casket with the help of House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi, D-California.

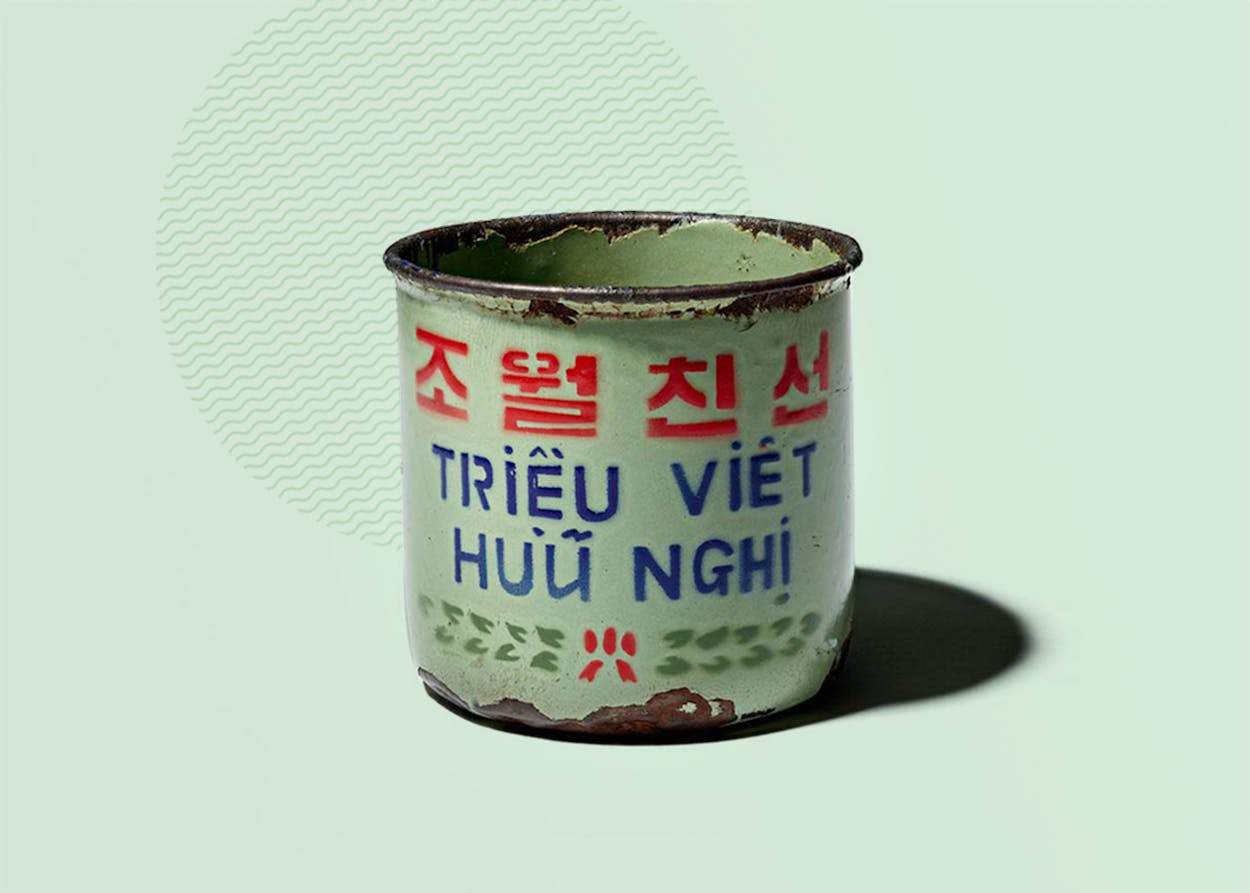

Johnson, 88, is retiring from Congress in January after nearly 28 years but before he leaves, the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History will honor him in December by including POW artifacts he donated this year, a tin cup and a tube of tooth paste, for an exhibit called, “The Price of Freedom: Americans at War.”

The self-effacing Johnson does not often talk about his exploits—like being a Top Gun instructor and lead member of the Air Force’s elite acrobatic flying team, the Thunderbirds, or his bravery in nearly seven years of captivity, including three in solitary confinement—but he said just ahead of Sunday’s Veteran’s Day commemoration that he wanted younger generations to know what veterans sacrificed for the country and what even two simple objects could mean for survival.

“When our captors told us to get ready to return home, I decided to smuggle out some items with me—my toothpaste and tin cup,” Johnson said when he donated the objects.

“I took these items for two reasons. The first reason was that I wanted to be prepared in case they had once again lied to us. These were my only possessions, and they were vital. But I also brought them as a future reminder.”

Both artifacts turned out to be much more than what they were intended to be—the cup a vital communication device used by tapping between, walls and the tube, which was made of lead and acted as a writing implement.

“The tin cup served many purposes, but most importantly it was a way for me and my fellow captives to communicate,” he said, when they were kept in solitary confinement in small concrete cells. “We would hold our cups against the wall, and it served as an amplifier to hear the tap code.”

How did it work?

The first flyers shot down were still together in a Hanoi prison early-on and one remembered “the tap code” that was a grid of 25 letters of the alphabet, minus the letter K, with taps and pauses for the listener to figure out the message.

“The tap code wasn’t too hard once you got the hang of it. It was set up like a grid: five letters across and five letters down,” Johnson said in a talk to constituents. The POWs would place the mouth of the cup against the wall and hold their ear against the cup’s bottom and tap against the wall.

“That’s how I learned French,” said Johnson. It was close friend, Bob Shumaker, a Navy flyer who would eventually be named a two star Rear Admiral, who was housed next door to Johnson and taught him French words.

“For three years we never saw each other,” said Shumaker in an interview. But when they did meet, said Shumaker, “His French was better than mine.”

The tooth paste tube was used as a pencil to draw figures on pieces of toilet paper that the POWs would then use to play chess on a mesh board.

“That tin cup was a lifeline for so many years,” said Johnson at the Smithsonian ceremony, “and it reminds me of God’s faithfulness to provide friendships that give you strength to survive through even the darkest times.”

Johnson has been one of the congressionally appointed members of the Smithsonian’s board of regents for many years. The American history museum anticipates, according to a spokesperson, that the Texan’s artifacts will be on display “by year-end.”

Johnson said that a quote that was etched on the Hanoi prison walls by another POW was something he’s never forgotten and was particularly appropriate for the exhibit that will be titled The Price of Freedom:

“Freedom has a taste to those who fight and almost die that the protected will never know.”

- More About:

- Texas History