One sunny afternoon in February 2014, Buck Birdsong heard a low cry echo across his Longview ranch. One of his cows, a recent mother, was wailing relentlessly, a slow beat of deep, frantic moans. He jumped in his beige F-250 to investigate, rumbling over the ranch’s winding dirt roads, through the pasture, and out toward the shallow, moss-covered pond that sits near the back of his land: 112 wide-open acres nestled amid the Piney Woods of East Texas and punctuated with a few clumps of elm trees, where his small herd of cattle often gathers in the shade.

As he approached the pond, Buck saw a single calf lying beneath a tree. He quickly realized why its mother had been bawling. The calf lay stiff and still, its dark, velvety coat cold to the touch. It had been dead for hours.

He grabbed the 250-pound calf by its legs and rolled it over, searching every inch of the animal for a possible cause of death. Buck had been raising cattle for a long time—this ranchland had been in his family for more than a century—and he was accustomed to losing the occasional animal, even the young. There are a lot of ways for a calf to die. It could be as complicated as a rare hereditary disease or as simple as nibbling on a few too many acorns or on a piece of toxic trash that had blown in from the road. But if the calf had been sick, Buck hadn’t noticed, and at first glance there was nothing obviously wrong with it besides streaks of dried scour (diarrhea) on its backside. He thought the animal might have been dehydrated, since it lay so close to the pond.

But then Buck saw what looked like a bullet hole on the calf’s back, and he surmised that maybe a stray shot had escaped from the woods of the hunting lease that borders about a third of his land. More likely, he knew, the hole was probably a peck mark from a crow or vulture. Erring on the side of caution, Buck called the Gregg County Sheriff’s Office and filed a report with the deputy who came out to the ranch. With no clear cause of death, the two men agreed, the dead calf was simply an anomaly. When the deputy left, Buck fired up his tractor with its front-end loader, dug four or five feet into the earth—just deep enough so varmints couldn’t reach the carcass—and rolled the calf into its grave.

A few days later, he heard the wailing of another cow. He rushed over to the pond and discovered a second calf, also dead, lying beneath the same elm tree. Buck rolled the animal over but couldn’t find a hole like the one he’d puzzled over on the first—though he did see streaks of scour. One dead calf could have been a freak occurrence, but two such similar deaths, so close together, surely meant that something was wrong. Buck loaded the lifeless animal into the bed of his truck and drove twenty minutes to the veterinarian’s office of Randall Spencer, in nearby Gilmer.

Wielding a pair of hedge clippers, Spencer opened the calf at the sternum, reached inside, and, one by one, pulled out the heart, the lungs, the kidneys, the liver, the intestines, and the spleen, slicing them up and carefully inspecting their contents. It wasn’t until later, when one of Spencer’s colleagues reached his hand into the last of the calf’s four stomachs, that they found something unusual. He pulled his hand out and spread his palm, revealing a small pile of a type of grain that can be toxic to cattle. Buck had never fed that particular grain to his herd, and when he returned home and searched his land, he found no trace of it anywhere. How, he wondered, had his calf ingested it?

Within a week of the vet visit, Buck heard yet another distress call coming from one of his cows. This time, the calf he found by the pond was close to death. It was wobbling unsteadily, as though it were drunk, and it had the same streaks of sickly gray scour running down its backside that he had noticed on the two dead calves. Buck loaded the calf into his blue gooseneck trailer, guiding it carefully through the chute, and raced to Spencer’s office, the tall pines that line Texas Highway 300 whipping by his window in a dark-green blur.

After examining the calf, the vet told Buck that it was possible the animal had licked a discarded car battery. Buck left the calf with Spencer and again searched his property, this time for a battery, but again he found nothing. A couple mornings later, he got a phone call from Spencer. The calf had died overnight—there was nothing he could have done to save it. Spencer had already performed a necropsy on the dead calf, and he told Buck that he’d found the same suspicious grain inside it.

Over the next four years, fifteen more of Buck’s calves would die. Investigators with the sheriff’s office, a Texas game warden, and even a special ranger with the Texas and Southwestern Cattle Raisers Association have worked the case, but so far, none have been able to identify any leads. The cause of death, however, is clear: the same toxic grain has been found inside each dead calf. Someone, it seems, is intentionally killing Buck Birdsong’s calves.

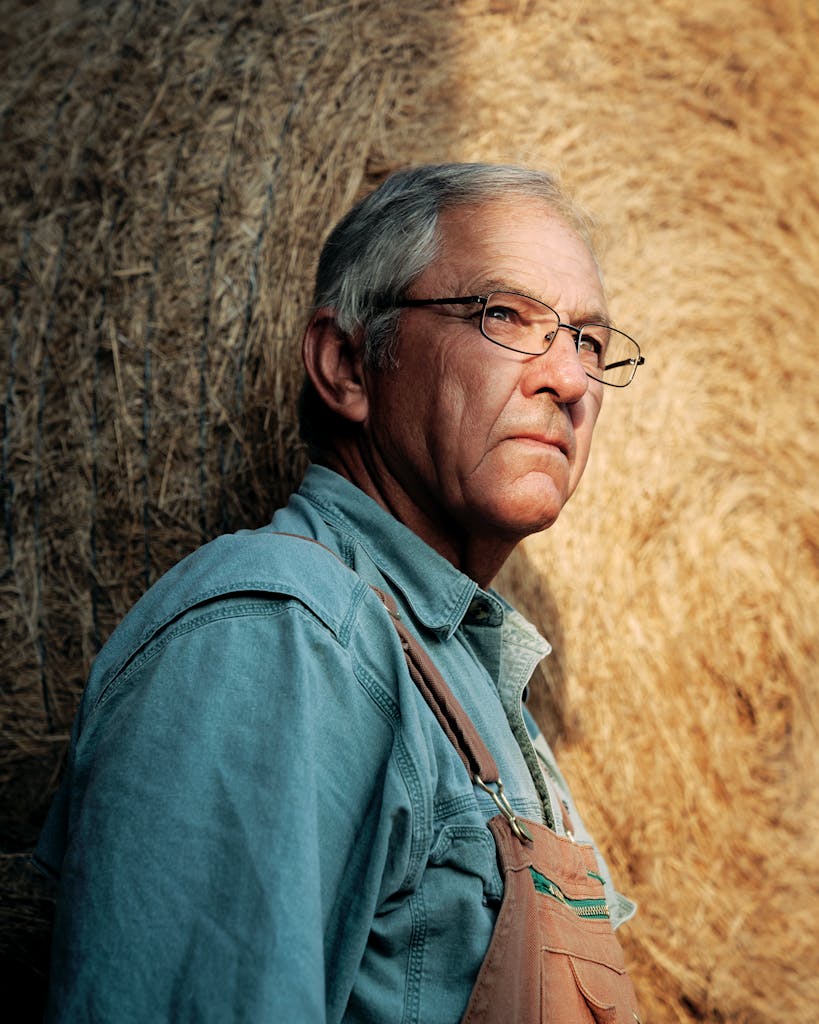

The Birdsong family name runs deep in Longview. Buck’s grandfather, great-grandfather, and uncles all owned cattle ranches in the area. Birdsong Street cuts through the southern part of town. Buck, who is 68, says one of his earliest memories is of his grandfather’s ranch just north in Pittsburg, where his father, who served for years as Gregg County clerk, frequently brought him as a little kid. Buck couldn’t have been more than three when his grandfather’s car got stuck in the muddy pasture one day. As his parents would later tell the story, Buck’s grandfather had to drive the tractor to pull it out, so he stood Buck, still in diapers, on the front seat of the car and told him to steer.

During the summertime when he was a teen, Buck would wake at three-thirty to milk the cows on one of his family’s ranches, go tend to the beef cattle on another family ranch during the day, and then return to milk the dairy cows once more. When he’d finally get home at six-thirty, sweaty and exhausted, he’d sit down for dinner and then go straight to bed, only to wake up early the next morning to do it all again. But he loved the life, and he knew from an early age that he would always want to be around cattle. He graduated from Texas A&M with degrees in journalism and animal science—his classmates called him the “animal evangelist”—and he almost took a job writing for a cattle industry trade magazine before he accepted one in public relations with Southwestern Electric Power Company in Longview. Even while he was raising three daughters with his wife, Becky, and working for SWEPCO, he’d return to the nearby ranch that his dad had bought from some cousins in the sixties, working in the mornings and coming back for more in the evening hours. When his father died, in 1986, Buck took over the ranch’s cattle operation for good.

Each morning at the ranch these days, Buck wakes at six, reads the newspaper, and then pulls on his grass-stained overalls and tucks them into his work boots. By seven, he’s heading out to check on his cows, his truck disappearing into the hazy morning light. The calves are Buck’s biggest source of income on the ranch—feedlots buy them and fatten them for slaughter—and if everything goes right, he can make a modest profit. But a cattle rancher’s future is as volatile as the East Texas sky. In contrast to the reliable drumbeat of his daily routines—mending fences; killing invasive plants; cutting and baling hay, should rain permit it to grow—Buck, like all independent cattle ranchers, is defenseless against the vagaries of what seem like a thousand forces beyond his control, from foreign trade wars to the weather.

A major drought has plagued some part of Texas at one point in every decade of the past century. When drought strikes, grass-fed cattle have no grass to eat, so ranchers like Buck have to either sell off most of their herd or spend more money on feed. And when demand for feed is high, so are prices. From 2010 to 2011, Texas experienced the driest twelve-month period on record, and the state’s farmers and ranchers posted a $7.62 billion loss, dropping the statewide cattle herd, the nation’s largest, by about 600,000 head.

Sometimes, of course, too much rain can fall. In 2008 Hurricane Ike killed up to five thousand Texas cattle and flooded coastal pastures with its saltwater storm surge. When it rains at Buck’s ranch, cars have a tendency to skid off the road bordering his land and career through the perimeter fence, one time even splashing into the pond. He had to replace one wooden corner fence post with a sturdy, crash-resistant metal bracket anchored in concrete.

Buck’s herd consists of about fifty adult cows and, after calving season each fall, an additional fifty babies, some of whom he’s had to pull out of their mothers by hand. Even for a small herd like his, the operating costs are enormous, and they have only increased over time. When he bought his first tractor in 1985, it cost him $12,000. When he needed to upgrade a few years ago, it set him back $63,000. It’s the same story with mowers, trailers, balers, rakes, feeders, and fertilizer.

Being an independent rancher is simply not financially attractive, and by 2012 there were 20,000 more Texas farmers age 70 or older than there were Texas farmers between the ages of 25 and 34. Aging ranchers are left with little control over what will happen to their land when they’re gone, since their sons or daughters are often uninterested in continuing the ranching tradition they’ve inherited. The land might be sold to become the latest tentacle of an encroaching suburb. Or it might be snapped up by larger farming corporations, which are slowly starting to squeeze out independent cattle ranchers like Buck—just as they already have done to poultry and hog farmers—in their march toward industry domination.

Buck’s done his best to keep cattle ranching in the bloodline. His daughters also have fond memories of spending time out in the pastures with the cows, and his grandchildren like to play with the animals and give the calves names. His favorite family photograph is of his grandkids propped up on golden bales of hay stacked in the barn. Each Christmas at the ranch, Buck gives his daughters packages of fresh beef.

If a terrible drought returns and stays for good or should the cattle market ultimately prove too costly for Buck’s ranching to survive, then that Christmas tradition might someday come to an end. And with the longevity of most small cattle ranches already in question, the dead calves have made Buck’s grip on the future all the more tenuous.

Buck is not one to let his emotions show, save for a quick smile or the slight furrow of his brow. A trucker hat usually covers his shock of gray hair, shielding his round cheeks and nose from the sunlight; his eyes are conditioned into a nearly permanent squint. He and Becky, a retired schoolteacher and university instructor, often sit at the dining table in the redbrick ranch house they built in 2000 and watch the late-evening skies darken slowly over their pasture. Sitting there one day this summer, Buck gazed out at a wall of gray thunderclouds that had appeared out of nowhere and spoke softly. “I’ll just wonder, you know,” he said. “I’ll look at thirty calves out there in the pasture and say, ‘Well, I wonder which ones will be next?’ ”

For four nights, he sat on a bucket behind the cover of the trees, staking out the pasture through his night vision goggles.

In more than two thousand investigations over a twenty-year career as a special ranger with the Texas and Southwestern Cattle Raisers Association, Scott Williamson, who now serves as the executive director of law enforcement and theft prevention, has never seen a case like Buck’s. “Typically, anything we saw was either small numbers or ended up tying back to more of a prussic acid poisoning, which is just a natural poisoning of grasses that come under awful [drought or frost] conditions and can kill cattle in a short period of time,” said Williamson. “It’s just an act of God through a natural process. But I have personally never worked a case of intentional poisoning.”

Investigators are sure it’s intentional. “Our team has looked at multiple possibilities,” Gregg County Sheriff’s Office spokesperson Joshua Tubb said. “At this point, they’ve been able to confidently say that they believe that this is being done by a person intentionally.” The one factor tying all of these dead animals together is the grain inside their stomachs, although investigators would rather not reveal the specific grain and the method they believe is being used to get it inside the calves, since it’s just about the only thing they have right now that bears any semblance to a lead.

About that grain: it can ferment in a cow and cause acidosis, a painful process that causes diarrhea and dehydrates the animal, just as happened to Buck’s calves. In large amounts, it can be deadly. But Spencer, the veterinarian, wasn’t sure the amount of grain he had found in the calves was enough to kill them on its own. So he and Buck tested for just about everything they could think of, sending tissue samples from the dead calves and the grain to the diagnostic lab at Texas A&M, hoping to find that the grain had been soaked in strychnine or warfarin or any other specific toxin that could spur investigators on a trail that might lead to the killer. Nothing came back positive, leaving only the grain. Invesigators continued to search Buck’s land, too, for other culprits, but found none. No residual contaminant from old oil wells, no feral hog poison, no lead.

There’s no pattern to the killings either. Their timing appears to be almost random. For almost a year, from 2015 to 2016, there were no calf deaths at all on the Birdsong ranch. Then they started up again. “The investigative value of the evidence and information we’ve been able to gain so far has been very, very, very limited,” Tubb said. “We don’t have it happening to other people in the area. We don’t have anyone coming forward that may have seen something out of the ordinary.”

“The unusual thing about this case is, Buck is a nice guy,” Spencer said in his office. “Usually, when you get into these deals where somebody is poisoning somebody else’s animals, they are not the cream of the crop people in the world.” Someone will get pissed off at a neighbor and use antifreeze or rat bait to kill their dog. “It is usually not somebody like Buck who is involved in something like that. He is an upstanding citizen, always has been.”

Buck has no ongoing feuds with family members and no disgruntled business partners, and he’s friendly with his neighbors. Like his father, he has upheld his family’s tradition of civic involvement, leading youth Bible study groups at his ranch and serving as chairman of the Good Shepherd Health System board. That’s earned him respect within his tight-knit rural community, but it hasn’t helped influence anyone to come forward with information about the crimes.

But even a good guy like Buck has likely stepped on a few toes over the years. Early in the investigation, detectives with the sheriff’s office asked him if he could think of anyone who might hold a grudge against him. No one came to mind immediately, but that night, he and Becky started brainstorming. The next day, Buck called and gave a detective three names: a man he’d had to fire when he was chairman of the hospital board; another man who was out on parole after he was caught breaking into Buck’s house years ago; and an acquaintance Buck had worked with in some community organizations and with whom he had a prickly relationship. Tubb said investigators followed up on the names, but they produced zero persons of interest.

The sheriff’s office then identified a group of teenage troublemakers as possible suspects, pranksters who might have been killing the cattle just for fun. But, according to Buck, the investigation into that group didn’t turn up any hard evidence, and the killings continued even after most of the teenagers moved out of town, virtually eliminating them as suspects.

At one point, Buck himself was a suspect. But when questioned, he told a detective that his calves aren’t insured or financed; there’s no monetary motive for him to kill them.

Buck’s land is extremely desirable—he said a neighbor recently sold his ranch for $40,000 an acre—but no one has pressured him to sell the ranch. There’s oil there, of course, and the Birdsong family has leased part of the land to a drilling operation called Dallas Production for years. There are oil workers and company contractors on the property all the time. Buck said Dallas Production has been cooperative throughout the investigation. One of the company’s workers even showed him footage from the dashcam on his truck after he spied a suspicious car lingering behind Buck’s property. When the worker drove toward the car, it peeled out and sped away. Buck said he turned the footage over to detectives but never heard about it again.

As the investigation dragged on without surfacing any leads, Buck began to take matters into his own hands. After the first few calf deaths, he bought motion-triggered game cameras and placed them across his ranch, setting them to capture about ten seconds of video if anything—or anyone—set them off. Buck would check the cameras once or twice a week, poring over the footage, but the only thing the cameras caught were oil workers passing through his property to the wells.

After a fourth calf died, in 2014, Buck took a pair of night vision goggles that Becky had bought him for Christmas and went out into the pasture after dark, hoping to catch the perpetrator in the act. For four nights, he sat on a bucket behind the cover of the trees along his fence line, so that he could see almost the entire pasture, staking out his land through the night with a cooler full of water and Gatorade beside him. He was alone with his thoughts, and all the possible scenarios and unanswered questions began running through his head again and again. But by the time the sun came up, he’d be no closer to catching the killer than he was the first day he heard the terrible wailing of the mother cow.

Last Christmas, Buck was on high alert. His daughters, their husbands, and his six grandkids had all gathered at the ranch, as they do every year for the holiday. The fall calving season had recently concluded, so Buck’s pastures were full of babies. He went out to patrol the ranch every few hours, driving the fence line. On Christmas Eve, he found one dead calf. The next morning, just before the family was going to open presents, Buck went out to the pasture for one more go-round, just in case. He found a calf on the ground, breathing slowly, with the dreaded gray-tinged scour streaking down its backside.

He called his daughters out to help him load the calf into his trailer, hoping to rush it to the vet. But the animal died before they even made it off the property. As his daughters cried, Buck walked off. “I’ll be back in a minute,” he told them. He drifted over to the shed by the ranch house and went inside, where he sat alone, seething with anger and frustration. When he emerged a few minutes later, he rejoined the family inside the house to open presents with the kids, trying with only limited success to hide his sadness. Later that night, after the grandkids were asleep, Buck slipped back out into the barren winter pasture and buried the dead calf in the dark.

“I think he just felt defeated,” his daughter Lori Aldredge said later. “It was like whoever was doing this got the upper hand on that day. They took something away from him on a day that was supposed to be so important. You know, they kind of . . . they got to him.”

After two more calves were killed that spring, Lori had had enough too. Grasping for something, anything, more to do, she turned to Facebook. “Anyone that knows me well knows that I’m a daddy’s girl,” she wrote. “I need HELP!” She wrote about the eighteen dead calves, as well as the complete lack of leads or suspects, and included a grisly photo of the latest calf corpse, which had to be pulled out of the pond where the animal had died.

The post went viral, piling up more than four thousand shares. Commenters largely expressed disbelief that the deaths could be murders. Many offered their self-proclaimed expertise as ranchers or vets, hoping they could provide the nugget of information they thought to be so foolishly overlooked by Buck and his family, the one that would finally close the case

Everyone had a theory or a quick fix. Put up game cameras, one suggested. (Buck had.) Was it blackleg? one commenter asked. (None of the calves exhibited symptoms of the fatal disease.) Leptospirosis? No. White snakeroot? Bad bull semen? Larkspur? Nightshade? Hemlock? No, no, no, no, and no. Get a Great Pyrenees guard dog. Get a Doberman. Buck has had dogs on his ranch, and they’ve never done much good. I’d sit out there all night with night vision goggles, someone said. Of course, Buck had done that too.

People were just trying to help, but as more folks shared the post, the theories became increasingly ugly. Don’t forget about immigrants in your area, one commenter said. They even shoot livestock thinking it’s funny. Several commenters suggested that animal rights activists were behind the killings. Another said someone must be dropping the toxic grain from a small airplane. One woman called Lori and claimed that a satanic cult was behind the deaths. Lori dismissed the idea at first, but the more she got to thinking, she figured maybe it wasn’t so crazy. After four years without any logical motives or leads, maybe it was time to consider that too.

Lori’s post spurred three local TV news stations to bring their crews to the ranch for the story. The Birdsongs waited hopefully for someone to call with a lead, but no one did.

“I’m preparing my mind that this is going to happen again,” Buck said recently at his dining table. “I’m hoping it doesn’t, but I’m preparing for it. I just wish they’d catch him and it would stop. I’m not so interested in prosecuting him and all that; I just want it to stop. Give us back our world.”

On a recent Thursday morning at the ranch, Buck drove out into the pasture, as he has so many times before, to see his cows. He hopped down from his truck and walked up to them, a hand extended to their muzzles. By this late in the summer, he had only two calves left unsold, so it was a rare stretch when he didn’t have much to worry about. Even the cattle seemed more at ease than they had in months. “Hey, mama,” he said to them softly, while they nuzzled their wet noses in his open palm. “Whatcha say, babies?”

With calving season again approaching, Buck knows that he’ll soon bring more babies into this world. He also knows that some of those babies likely won’t be long for it. He has considered giving up on ranching, and not just because of the streak of deaths visited upon his herd. He has already accepted that he’ll probably be the last in his family’s line of cattle raisers. His daughters already have careers and families of their own, and they likely won’t want to carry on their father’s business. But that’s a problem for a later time. Buck must first weather more immediate crises, like the dry spell currently choking his pasture or the ongoing trade war between the United States and China, which has prompted harsh tariffs on beef exports and could hurt profits for cattle ranchers.

Maybe he’ll just sell the whole herd, he thinks. Just plant pine trees out there. But he can’t bring himself to do it. “You can’t talk to pine trees,” Becky reminds him.

Back in the Birdsong kitchen, a low rumble rolled over the ranch. “Is that thunder?” Becky said. “Yep, I think so,” Buck replied. By this time of year, he’d usually be finished with his second cutting of hay and on his way to cutting a third. But he’d only cut once this year and was desperately hoping for a shower to replenish his pasture. “We need some rain,” Buck said. “We need some rain.”

Correction: This story has been updated to fix a spelling. The Texas town is Pittsburg, not Pittsburgh.