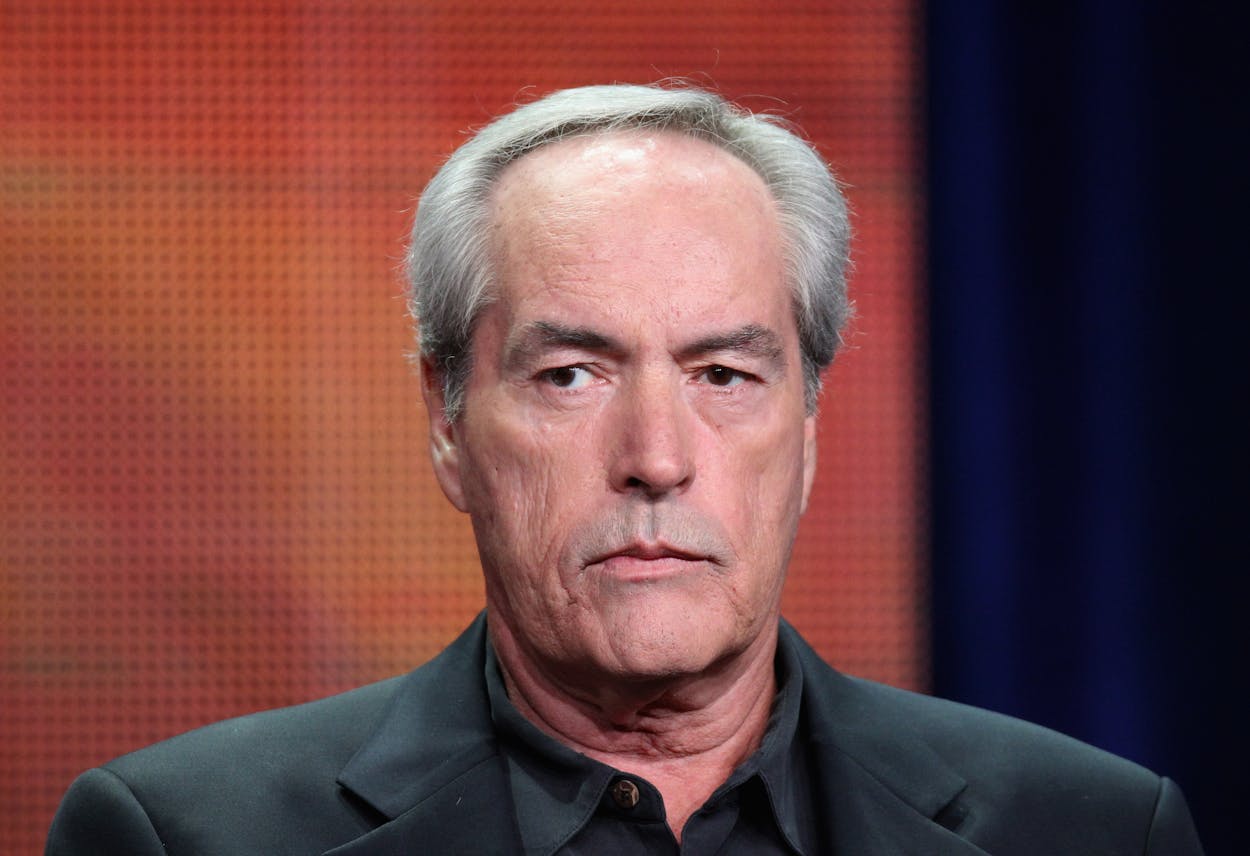

Quarterbacking a high-school football team is probably as close to nirvana as a West Texas adolescence gets, and that’s what Powers Boothe did—pretty well, too, apparently—at Snyder High School in the mid-1960s. Until, that is, his senior year, when he freaked everybody out by deciding he liked theater better. “Some of the coaches questioned my manhood,” he told Texas Monthly back in 1996, and let’s bet he was putting it mildly. But it didn’t hurt that Snyder had (and has) an unusually renowned drama program for a small-town high school. Today, it claims Boothe, who died on May 14 at age 68, as its most distinguished alum.

After getting his M.F.A. in drama at Southern Methodist University, he did an old-school apprenticeship in stage work, from a stint in the Oregon Shakespeare Festival’s rep company to his one Broadway appearance in a 1979 one-acter titled, appropriately enough, Lone Star. (In a role written with him in mind, he played a former Texas high-school football star newly returned from Vietnam—except for the Vietnam part, maybe as close to autobiography as he ever got.) But Boothe was made for screen acting, and the key to his particular memorability is that movies were the lesser showcase for his gifts.

He did just fine in film when he got the chance, from his gallivanting turn as an outlaw in the 1993 Western Tombstone to his taut Alexander Haig in Oliver Stone’s Nixon. But his acuity and gift for stillness were ideally tailored to TV, which most actors of his generation were wont to treat back then as an inferior, less nuanced and expressive medium. His career was a terrific education to viewers in the rich opportunities TV offered to an actor able to rescale his toolbox to fit the home screen’s closer observation and more measured, detail-accumulating tempo.

The distinction has largely eroded today, since most people now watch movies and TV series at home on the same screen. But back when people experienced movies—new ones, anyway—mainly in theaters, the big screen’s gigantism was friendlier to broad-strokes acting, while TV’s intimacy and serial format invited audiences to contemplate minutiae and subtly graduated behavioral tics. Boothe’s fellow Texan and near contemporary Tommy Lee Jones exemplifies the difference, since Jones thrives on film’s magnification of his performing style and TV always cramped him somewhat. Boothe, on the other hand, knew how to hold the TV audience’s attention by always seeming to leave something unstated even at his heartiest.

His breakthrough role was in 1980’s two-part miniseries Guyana Tragedy: The Story of Jim Jones. Rewatching the climactic monologue when Jonestown’s cult leader talks his followers into committing mass suicide, you’re struck by how, well, leisurely it is, because Boothe doesn’t make the mistake of pitching things high from the start and then having nothing new in reserve. These people are already under Jones’s sway, and he doesn’t need to rant at them; he just needs to wheedle them into seeing their imminent deaths as one more privileged experience that demonstrates they’re special. Boothe’s sinuous modulations from flickers of an inner hysteria Jones can’t betray to his flock to moments when his attention seems to wander as he succumbs to groggy tropical torpor are really extraordinary. Despite the scene’s urgency, Boothe won’t be rushed into hitting a false note or peaking too soon.

Guyana Tragedy won him an Emmy, but it didn’t turn him into a star. Maybe his Jim Jones had been a little too spooky for comfort, or maybe—no, I’m not kidding—his name had something to do with it. “Powers Boothe” would have just looked right for the third-billed actor in a 1930s comedy, but it had a faintly preposterous ring half a century later. He had the right good looks to be a leading man, but he lacked the temperament for it—which may not have bothered him one bit. Instead, he evolved into one of the handsomest character actors on TV, playing against his face’s attractiveness by dependably finding ways to indicate it was a facade.

Boothe was good in Philip Marlowe: Private Eye, based on Raymond Chandler’s short stories and the first dramatic series on the then relatively marginal HBO. Boothe deliberately isn’t playing the mythic Marlowe that Humphrey Bogart permanently glamorized. Less white knight than disgruntled pawn, his Marlowe is a faintly seedy, not altogether appetizing guy whose abrasive wisecracks don’t sound especially cocky or clever. They’re part of an act he’s got to sustain for professional reasons without enjoying it much, and Boothe’s wariness of how facile charm would only muddle this performance is very noticeable.

As the years went on, he also, inevitably, turned up in his share of shlock. It’s always easy to underestimate how vital it is for actors in his league to simply keep working, no matter the job; their sense of self depends on it. But if Boothe never became a star, he never declined into being a mere journeyman either. Even in roles that didn’t require much more of him than an authoritative camera presence and that forbidding, yet paradoxically seductive baritone—one of his great assets as he aged and his c.v. came to include lots of voice-over work in animated series—he could usually be counted on to add vagrant hints of labyrinths unknown to the audience, or for that matter the scriptwriters. And when a role came along that let the hints be less vagrant, his pleasure in exploring them was undimmed; he hadn’t let his sense of craftsmanship deteriorate.

Especially once he was in his fifties, he was often cast as men cynically at home with power: Vice President and then President Noah Daniels on 24, Senator Roark in both of Robert Rodriguez’s Sin City movies, Connie Britton’s tycoon father on Nashville. One reason he was so convincing in those roles was that, unlike the kind of actor who can’t resist editorializing by portraying the Dick Cheneys of this world as consciously—not to say gleefully—evil, Boothe always characterized them on their own terms: as hard-nosed success stories who don’t consider themselves malevolent, just wised-up and shrewdly pragmatic. As a result, the ideal Boothe part became defined as someone who’s fundamentally hollow at the core—but doesn’t mind, or anyhow doesn’t feel as uneasy about it as he’s been informed he ought to. Since he was equally at home in Westerns and contemporary pieces, it’s tempting to imagine a then-and-now mash-up of his movies that turns this distinctively American type—a man who’s empty and fulfilled at once—into an eternally recurring aspect of our national character.

No wonder his last great part was as the smoothie frontier entrepreneur Cy Tolliver in the brilliantly revisionist HBO Western Deadwood. When Tolliver arrives on the scene, Ian McShane’s Al Swearingen is the town’s crude business kingpin, but Tolliver knows that won’t last. Counting on his ruthlessness and coarse savagery to keep him on top, Swearingen is a primitive without any real capitalist guile, something his more sophisticated rival has in spades. Boothe plays Cy with a bluff geniality whose drollness is both blatantly calculated and masks a whole other level of calculation; his eyes are never colder than when they’re twinkling. But Swearingen doesn’t even realize he’s being sized up as a chump. On his end, Tolliver is so sure he’ll come out the winner that he can afford to bide his time. In a way, that could be true of the actor who’s playing him as well.