George Herbert Walker Bush—Texan by choice, oilman by trade, and forty-first President of the United States by popular vote—died in Houston late Friday at the age of 94, the oldest living president in the history of this country. His death follows by nearly eight months that of his wife, Barbara Bush, who died April 17. George and Barbara also hold the record for the longest married presidential couple at 73 years in January. The second longest married presidential couple was John and Abigail Adams, at 54 years, who are also the only other couple in U.S. history whose son also became president.

Bush was the living patriarch of one of the great American political dynasties. His father was a U.S. senator, and Bush had one son who had been governor of Texas and forty-third president, another who had been governor of Florida, and a grandson, George P. Bush, who is the current land commissioner of Texas. While the Bushes never rivaled the Kennedys or the Roosevelts for glamour, they were unequaled for pragmatic conservative politics.

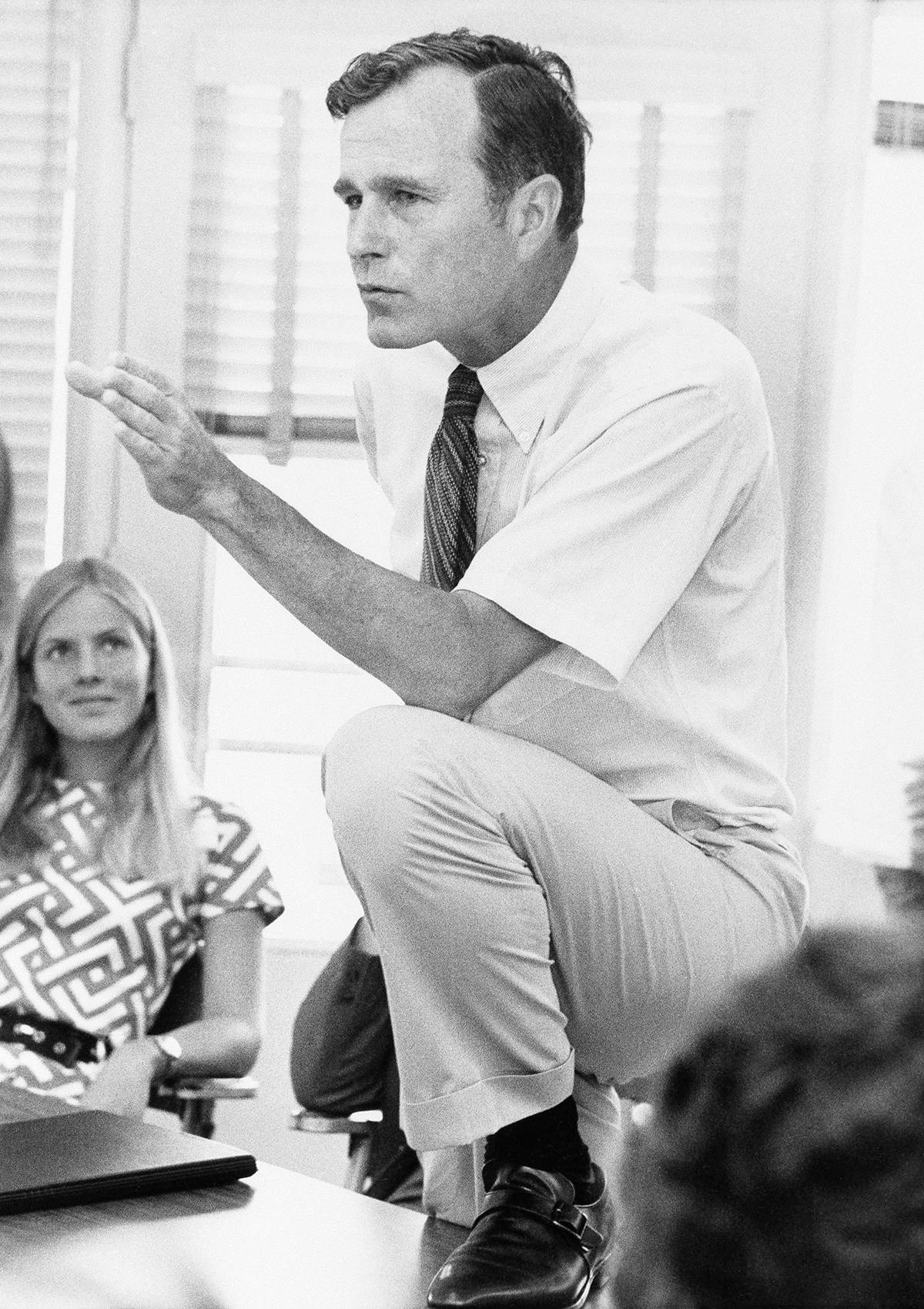

The future president first appeared in the pages of Texas Monthly in 1974 as part of a profile of the Texans who were heading the Democratic and Republican national committees. As writer Al Reinert said of Bush:

He has what political oddsmakers like to call “magnetism,” that being a kind of aura about him that falls just a notch below actual “charisma.” He gives the impression of being taller than he is, which is tall enough anyway, his features not so much handsome as strong, his gestures emphatic yet relaxed (not nervously exaggerated, like Nixon’s), his voice firm and authoritative, sentences crisply articulate. He seems like a man predestined to stand behind podiums and give speeches.

Yet there are less stately touches: His hair keeps falling in his face, he laughs easily, is casually witty, self-mocking. That’s something politicians carefully cultivate, that seeming naturalness (the easier for us stumbling voters to identify with them), but on Bush it still seems, well, natural.

As they say in Vegas: He’s a Class Act.

Few things say Texan more than moving here and adopting the Lone Star State as your home for life. A New England Yankee from Yale, Bush arrived in 1948 and made a fortune in the oil fields of the Permian Basin and through offshore oil drilling. In Houston, he was a pioneer of the Republican Party and served that city in Congress. Over the next quarter century, he was the ambassador to the United Nations and China, chairman of the Republican National Committee, and director of the Central Intelligence Agency before terms as vice president and as the forty-first president of the United States. And all the while, Texas was home, even if it was just a mailing address at the Houstonian Hotel. When he was done with his remarkable career, he returned home.

In Houston—it was Houston every other weekend, no matter the effort required—the office ladies adored George Bush. Sometimes, if things got slow, Bush would exit his inner office in a flying ballet leap, just to make les gals giggle. Late one day, a little woman came by. She was a mousy sort, no makeup, poor dress—probably a hard-luck case. She wanted to see Mr. Bush. But the ladies had no time to tell him before he flew into the office in a twisting tour jeté. Then he saw the woman. He froze—on the ball of one foot, with his arms outstretched—and blushed crimson to the roots of his hair.

Bush was the son of Prescott Bush and his wife, Dorothy. He was named after his mother’s father, George Herbert Walker, who was known as Pop. The future president was first nicknamed Little Pop, but it soon became Poppy. Prescott Bush would serve Connecticut in the United States Senate. He was the treasurer of the first fund-raising drive for Planned Parenthood and was a key ally of President Eisenhower in the passage of the Interstate Highway System.

During World War II, Bush became a Navy pilot, and on September 24, 1944, was shot down by anti-aircraft fire while bombing a Japanese radio station. He bailed out and was rescued by a U.S. submarine, but his two crewmen were killed—one of whom had been a friend at Yale. After the war, Bush moved his family to the Permian Basin and founded an oil exploration company. They moved to Houston after he began specializing in offshore drilling. By 1964, he was deeply involved in Republican politics. He represented Houston’s Seventh District in the U.S. House and ran a traumatic and unsuccessful race for the U.S. Senate in 1970, losing to Democrat Lloyd Bentsen.

On election night, family and friends gathered at the old Shamrock Hotel. Bush knew it would be tight—his last polls showed the race even. But he knew he could win: Good things happen to good people. He had to believe. The family was in a suite, upstairs from the big ballroom with the band, balloons, and streamers. George and Bar were on a couch with their children—George’s arms around Doro and Marvin, Bar holding Neil and Jebbie. They turned on the TV . . . and it was over. Twelve minutes into the broadcast, after two years of work (seven years since he started for that seat), Walter Cronkite said his computers called the race for Bentsen . . . The one who didn’t cry was George Bush. He went around the suite, telling everyone what a great job they’d done. Then he was on the phone. “Well,” he’d say, “back to the drawing board.”

Bush ran for president in 1980 but lost to Ronald Reagan, whose outreach to moderate Republicans was to name Bush as his running mate. As Paul Burka wrote:

It has been a long and often frustrating journey since that first senatorial campaign. At 55, Bush is no longer the Whiz Kid of the Republican party but seems to have become its Good Soldier instead. The new role has not been without its rewards—by speaking up for the party during its darkest days, Bush built up the contacts and the IOUs that have enabled him to assemble a national organization—but it also has its downside. A Good Soldier doing his duty is something less than a charismatic figure. Indeed, one of the essential elements of charisma is the presence of a tragic flaw—a potential, however slight, for malevolence. The very effort of overcoming it can make a Lyndon Johnson seem larger than life. Bush never seems to take on such expanded dimensions. Though his spirit seems remarkably undaunted by a career of near-misses, the disappointments and defeats have changed him. He is different from politicians with virgin egos: reflective rather than glib, restrained rather than dramatic. The difference shows up in small ways. En route to the airport that post-Thanksgiving Sunday afternoon, Bush tempered his damning assessment of Jimmy Carter—“He’s just not up to the job”—by adding, in an almost musing tone, “You know, I really thought he’d be a good president. I briefed him on national security and I was impressed with his grasp of it.” Most politicians would never give a rival that much credit, much less admit misjudging someone.

For two terms, Bush served Reagan as his vice president before winning the White House himself. Burka told the state not to expect favoritism from the new president: “George Bush has never been a pork-barrel politician. He started out in politics at a time when most Texas conservatives became Democrats to preserve the state’s considerable influence in Washington; the rationale for being a Texas Republican was not ideology but clean government. Nothing in his two terms as vice president indicated that he had changed.”

As a presidential candidate, Bush had promised, “Read my lips, no new taxes.” But in the midst of a recession, he took responsibility for keeping the federal government operating by raising taxes. This angered his conservative base. He also successfully built a coalition to drive Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi army out of Kuwait, but many conservatives believed he had not finished the job by leaving the dictator in charge in Iraq. Then Dallas technology billionaire Ross Perot joined the 1992 election as an independent candidate because of his opposition to the North American Free Trade Agreement. Bush lost his reelection bid to Democrat Bill Clinton. Burka, again, in 1997:

Almost five years have passed since George Bush was president, enough time and distance for the debate over his role in history to begin. And so it has: This summer economist Robert Reischauer, the former head of the Congressional Budget Office, credited the much-disparaged tax bill of 1990, agreed to by Bush despite his “Read my lips: no new taxes” pledge during the 1988 campaign, with helping produce the prolonged economic expansion of the Clinton years. Others have read Bush’s parachute jump last spring, at the age of 72, as an attempt to eradicate the “wimp” label that had dogged him in the latter part of his career. On November 6 the George Bush Presidential Library and Museum at A&M will be dedicated. Advance copies of the first biography of Bush that covers his presidential years, Herbert S. Parmet’s George Bush: Life of a Lone Star Yankee, are already out. The likelihood that George W. Bush will be a candidate for president in 2000 will no doubt lead to still more scrutiny, so that the sins and triumphs of the father can be visited upon the son. All history, it is said, is contemporary history, and that is certainly the case with the presidency of George Bush.

In 2003 Bush sat down with former Texas Monthly editor Evan Smith for an interview. Bush’s eldest son, George W. Bush, was president. Another son, John Ellis “Jeb” Bush Sr., was the Florida governor. Smith asked the elder Bush how he filled his days as the Former Leader of the Free World.

Truman wrote a book, a chapter of which was called “What to Do With Former Presidents,” where he suggested they be honorary members of Congress with no right to vote, but they could sit in on stuff. That has no appeal for me. Of course, with the new president, and before that, with both George and Jeb running for office, I was disinclined to get out there and take positions and write op-ed pieces, and it’s just verboten now, because some enterprising reporter would say, “Look at this. Don’t I detect an iota of difference here between this president and number forty-three?” It’s better just to stay out of the limelight, sit on the sidelines, and go about my life. At times I miss making important decisions. At times I miss seeing my views out there. But it’s unimportant to Barbara and me when compared with the well-being and progress of our two sons in politics.

What’s interesting, I think, is that the press takes your silence as an indication of differences between you and the president. The fact that you’re not speaking out supposedly says something. When a friend of mine like Jimmy Baker or Brent Scowcroft says, “Well, we ought to do more about the Middle East,” the press says, “It looks to us like they’re reflecting what president number forty-one really feels but doesn’t want to say,” which is all bullshit, if you’ll excuse the expression.