It’s close to 10 p.m. on a Sunday, and a Rice University senior named Thomas Herring is hunched over a laptop in the Oshman Engineering Design Kitchen, on the north side of campus. To his right, a black notebook full of scribblings, its pages covered with extraterrestrial-like symbols you’d expect to find inside an Iowa crop circle, sits open on a table. Just some “calculus and kinematics,” the friendly 22-year-old coolly explains with a shrug.

In the past, the electrical engineering major has worked on largely theoretical robotics and artificial intelligence projects that might be unveiled years from now. Tonight, Herring and five other engineers are rushing to finish a project that is arguably among the most consequential in the world at the moment, one that could be deployed to the public as early as next week: a $300 3D-printable automated ventilator.

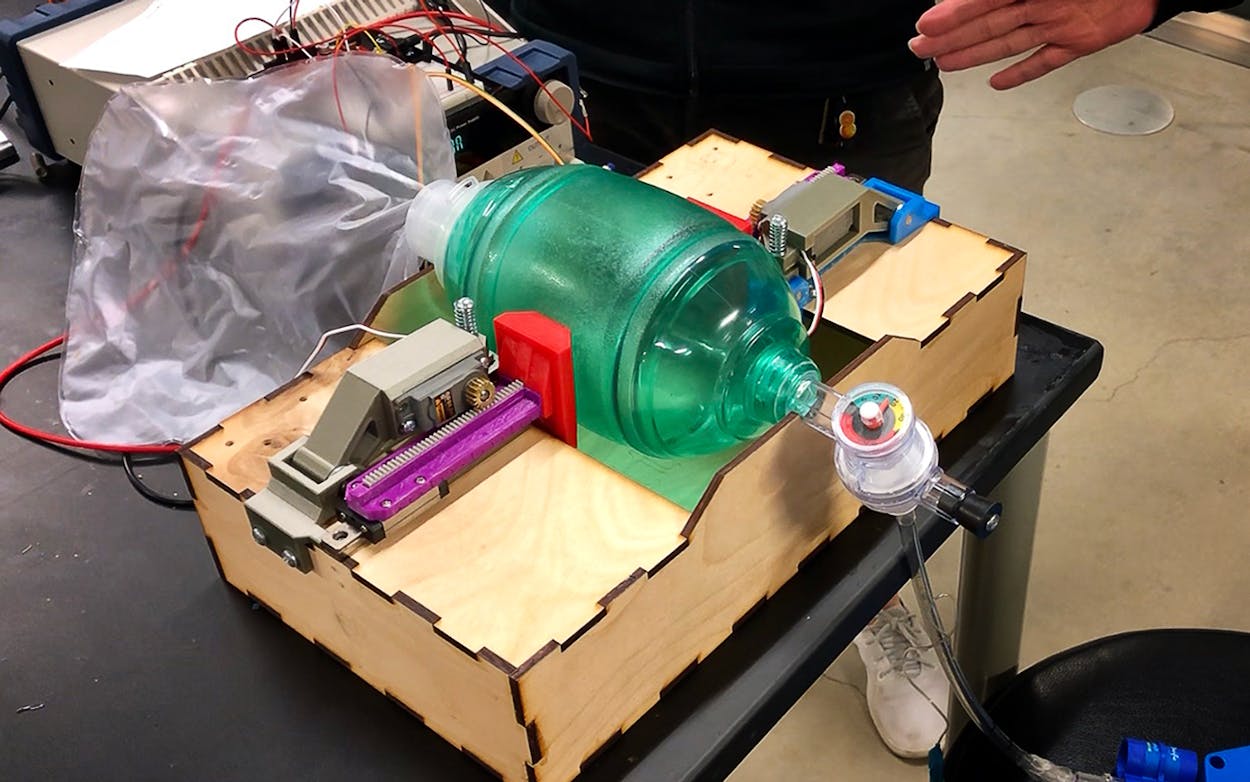

If successful, the ventilation unit—a DIY device that looks like the work of a high school robotics club—could go into mass production as early as next week, offering hospitals around the world a way to address a ventilator shortage that is expected to kill thousands of coronavirus patients suffering from the respiratory illness in the coming weeks. The national stockpile has close to 17,000 ventilators—less than a quarter of the 70,000 needed to combat even a moderate influenza pandemic, though a severe crisis like COVID-19 could require hundreds of thousands more, according to the New York Times. High-quality ventilators like the kinds hospitals rely on can easily cost $10,000 apiece. Faced with shortages, doctors might soon have to make tough decisions about redistributing them from older patients to younger, healthier ones, many experts believe.

Many hospitals have an abundant supply, however, of bag valve masks, which are hand-operated ventilators that are inefficient and difficult for one person to operate for more than an hour at a time; they require a rotation of people to keep the patient alive. The Rice prototype automates the pumping of the bag and can be specifically calibrated for each patient’s needs. With mechanized bag valve masks on hand, hospitals could buy themselves some time, allowing them to redistribute limited resources, move patients to other facilities, or allow family members the chance to say goodbye to loved ones who have no chance of recovery and might otherwise be taken off in-demand machines.

The Rice team expects to have their prototype completed by Tuesday and for human trials to be underway a day or two later. By the end of the week, they’re aiming for something that would normally sound impossible: receiving Food and Drug Administration approval in a matter of hours—not days or months.

“A lot of the work I do here as a student isn’t really applicable outside the classroom setting, so it’s really cool to work on a project where the effects are measurable in the number of lives it saves,” says Herring, who received special permission from school administrators to work on a campus that has been closed for the semester because of the coronavirus.

An early version of the device was designed by Rice engineering students working on a global initiative targeting worldwide ventilator shortages in 2019, but it wasn’t ready for the real world, according to Amy Kavalewitz, the executive director of the OEDK. As the coronavirus spread across the globe, overwhelming hospital resources, Kavalewitz began receiving emails from people searching for automated ventilators. So far, she’s received nearly two hundred requests from 37 countries, many of them from technicians and clinicians seeking the team’s blueprints.

Just over a week ago, with the requests for help pouring in, Kavalewitz assembled a five-person team, of which Herring is the only student member, to upgrade the machine while also building a website with instructions, pictures, and part lists that will allow the programmable ventilator to be reproduced elsewhere.

The Rice team believes they can eventually lower the cost of their units to somewhere between $100 and $200. The low cost was built into the engineering. The machines were designed using laser cutters and 3D printers, as well as parts that can be found in most hardware stores. “Houston and the rest of the U.S. may have manufacturers that can make these things by the hundreds,” Kavalewitz said, “but a small hospital in Malawi doesn’t have that luxury, but we’ll be able to give the plans to save lives.”

The team describes their pace as “controlled frantic.”

“We keep seeing the numbers of the dead go up, and you just know you have to translate that into getting to work,” says Danny Blacker, the OEDK’s engineering design supervisor, who says he’s logging sixteen-hour days seven days a week.

The Department of Defense is interested in their design and several Texas Fortune 500 companies have expressed interest in producing the model, team members say. The governor of Tennessee has also expressed interest in purchasing the machines once they’re completed.

“We’ve already had folks from the federal government reach out and say, ‘When you are ready for the FDA, just let us know,’ ” says Dr. Rohith Malya, an assistant professor of emergency medicine at Baylor College of Medicine and an adjunct assistant professor of bioengineering at Rice who has been advising the team with guidance from his work with COVID-19 patients.

The expedited approval process is a testament to the severity of the coronavirus crisis, which Malya says he’s witnessed firsthand in recent days.

Like many experts, Malya predicts the wave of patients overwhelming New York and New Orleans hospitals will begin to hit Texas in mid-April, putting severe strain on regional medical equipment, particularly ventilators.

“It would be very unusual for American parents to start bagging [using a bag valve on] their children for hours on end, knowing that if they give up their kid is going to die, but that’s where this virus could take us,” Malya adds. “That’s why mechanization becomes super urgent.”

- More About:

- Health

- Rice University