Three days after they were freed, the boy started calling him “papa” again. For more than a year, six-year-old Edwin and his father, Juan, had been locked up in separate immigration facilities. The boy had been held at a shelter for unaccompanied minors—one of at least 2,800 children separated from their parents by the Trump administration under a now-defunct “zero tolerance” policy. Juan had served time for violations of immigration laws in two federal prisons and later in a detention center in West Texas. Their only connection was twice-weekly phone calls during which Juan would try to cheer up Edwin, asking him about his daily life. But nine months into their detention, in February 2019, something slipped inside the boy.

“[Edwin] wouldn’t say ‘papa ‘on the phone with me,” Juan said. Worse, he’d started calling adults at the shelter “abuelo” and “abuela”—grandfather and grandmother. It was another marker of the toll that being ripped away, quite literally, from his father was taking on the child. “I believed I was going to lose my son,” he said.

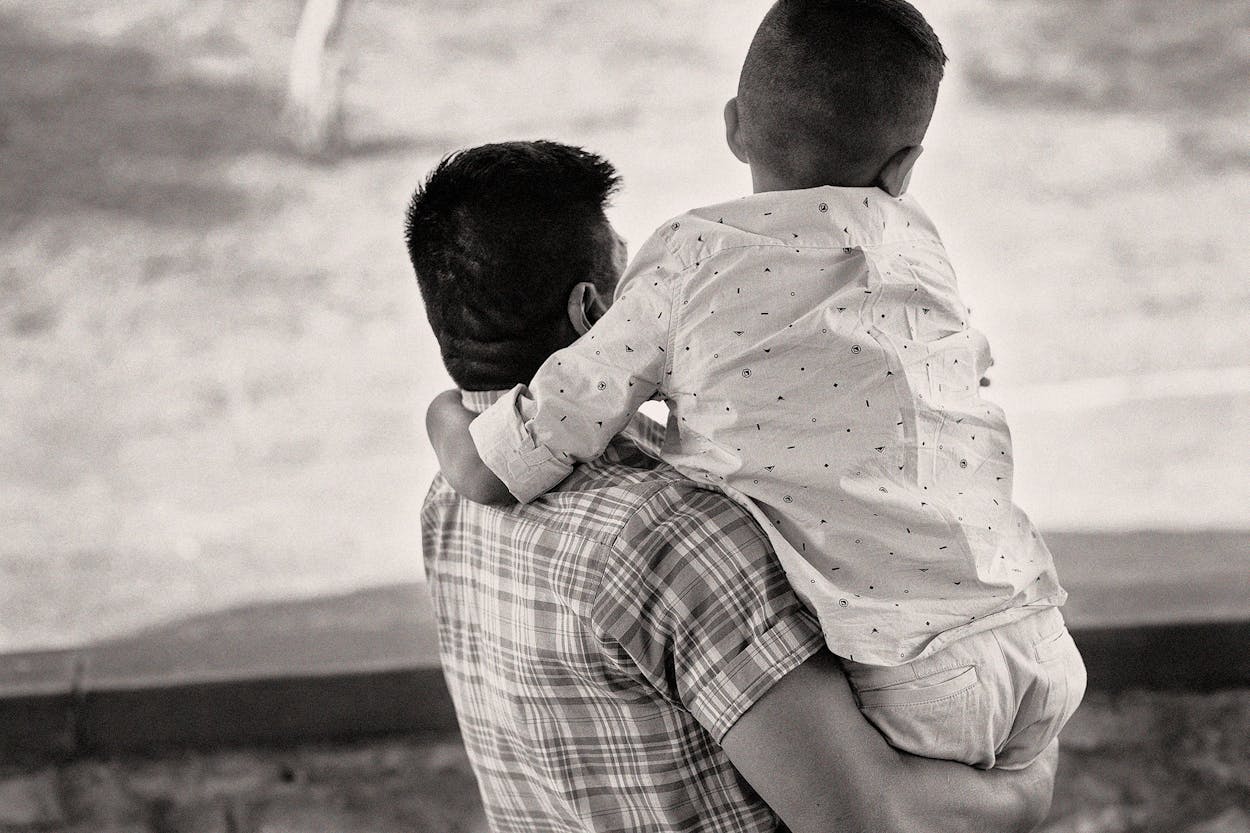

But on a windy May afternoon in a small park in El Paso, Juan, now 40, watches over Edwin, now seven, as the boy romps on a playground. It’s only been a few days since the two were reunited, and after a grueling separation and legal battle, some semblance of father-son normalcy is returning.

“He’s changed a little, but bit by bit he’s becoming closer to me,” said Juan, who is short and muscular, the result of working out six to seven hours a day in detention to relieve anxiety. “I share a bed with him and we play. And he likes exercising, too, so we work out together. … And he is starting to call me ‘papa’ again.”

While Edwin is drawing closer to his dad, his time in federal custody stripped him of the ability to speak with his mother, who stayed behind in Guatemala and only speaks a rare Mayan dialect.

“He’s completely lost his dialect. He hasn’t been able to speak to her directly. When I start speaking to him in my dialect he says, ‘what are you saying, I don’t understand you. Speak to me in Spanish, I don’t understand you,’” Juan said.

Regardless of the difficulties the family still faces, Juan and Edwin’s reunion was in many ways improbable. Legal experts believe Juan is the first parent separated from a child under Trump’s zero-tolerance policy to win permanent protection against deportation, thanks to a ruling in U.S. immigration court. Other families have either been deported or are pursuing asylum claims that could take years. Edwin and Juan also have the distinction of being separated longer than almost any other family—378 days. Edwin celebrated his seventh birthday more than six months into his detention.

When Juan fled Guatemala with Edwin in March 2018, he was already familiar with the journey north. Juan had come to the United States three times previously. He’d first come in 2001 when he was 22 to earn money. He made mistakes while living in Florida and Alabama, including a drunk-driving conviction, before voluntarily returning to Guatemala in 2007. Frustrated with the lack of work in Guatemala, especially for indigenous men like himself, Juan returned to the U.S. again in 2012 and 2014 but was apprehended both times by the Border Patrol and deported. Back in Guatemala, Juan went to work for a private bus company that was regularly extorted by a criminal gang and corrupt local police. Juan said he was regularly a gang target for shakedowns and death threats.

In the spring of 2018, he said, gang members and police came to his house and demanded that he kill three of his former bosses. “If you don’t do what we’re saying, you’re going to see that we’re not f—ing around, because first we’re going to kill your sons. We’ll kill them one by one. And then we’re going to kill your wife and we’re going to kill you,” recalled Juan. (Juan and Edwin’s names have been changed, because Juan fears that he and his family could otherwise face retaliation.)

He asked the gang members and police for two days to plan the murders. “We just grabbed whatever we could and left the house. We had no choice,” he said. Juan hid his wife and older son in another village and took Edwin with him to the United States. They surrendered to Border Patrol in southern New Mexico near El Paso on May 1, twenty-five days after then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced that every adult illegally crossing the U.S.-Mexico border would be prosecuted, a policy that required children to be split from their parents. (The administration abandoned the policy in June 2018 amid widespread condemnation.)

Juan told the Border Patrol agents about his situation in Guatemala and said he wanted to seek asylum. The next day, agents came to their small cell and told Juan, “Leave your son there. We only need you.”

The agents cuffed his hands behind his back. “When my son heard they were going to separate me, he started crying. I told him to be strong, you don’t know what’s going to happen.” Instead, Edwin launched himself at his father, wrapping his arms tightly around Juan’s head. The agents peeled the child away. “And that was the last time I saw my son” for more than a year, Juan said.

The vast majority of unauthorized border-crossers who face criminal prosecution are charged with illegal entry, a misdemeanor that usually results in a sentence to time served and deportation. But because of Juan’s prior deportations, he was slapped with a charge of illegal re-entry, a felony. He pleaded guilty and was held in federal prisons until he completed his six-month sentence in October. Juan was then transferred to a for-profit immigrant detention center in Sierra Blanca, about 90 miles southeast of El Paso.

At this point, Juan had very long odds of being able to stay in the U.S. Ninety-five percent of Guatemalan asylum seekers without lawyers lose their cases in immigration court, according to research by Syracuse University. Those with lawyers don’t fare much better; almost 70 percent fail to convince a judge they should be allowed to stay. Luckily for him, Juan got the help of volunteers from Kirkland & Ellis, one of the top law firms in the country.

The firm tracked down police reports in Guatemala and tapped expert witnesses to help Juan explain the dangers he faced if he was deported. “I told the judge all of this and the judge said, I want you here in this country. And that made me really happy,” Juan said.

On March 27, immigration judge Michael Pleters in El Paso ruled that returning Juan to Guatemala would violate the United Nations Convention Against Torture, a treaty that prohibits deporting a person to a country where he or she likely would face torture. Winning a Convention Against Torture case is extremely difficult; about 2 to 3 percent of all applications are granted, according to Immigration Equality, an immigrant rights group. In another highly unusual move, the Department of Homeland Security opted not to appeal. Juan was finally freed on May 9 and reunited with Edwin six days later.

Despite his court victory, Juan’s family situation remains unsettled. Unlike migrants covered under traditional asylum law, those protected by the Convention Against Torture don’t have the right to seek asylum for family members, said Ashley Neglia, one of the Kirkland & Ellis lawyers who represented Juan. Edwin will have to win his own asylum case in order to say in the U.S. So would his wife and older son.

Juan’s hopes for himself are simple: to buy a car and find a job. His hopes for Edwin are more expansive: “I just want to give him the best, and I hope that he can get a scholarship so that he can study and have a professional career.”

Cavorting on the playground, Edwin seems like any other seven year old. He says he likes pizza and McDonald’s, but not broccoli. He watches “Power Rangers.” He speaks primarily in Spanish. And although he’s forgotten his family’s Mayan dialect, he’s learned some English in his year at the El Paso shelter for migrant children.

When asked for an English demonstration, Edwin recites something he learned at the shelter: “I pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America …” He knows every word.

- More About:

- Family Separation

- El Paso