Featured in the Dallas City Guide

Discover the best things to eat, drink, and do in Dallas with our expertly curated city guides. Explore the Dallas City Guide

Known for his cinema verité explorations of American institutions, the documentary filmmaker Frederick Wiseman trained his camera on Dallas’s flagship Neiman Marcus location in 1982. To watch the resulting work, The Store, now is to travel back to a far less troubled age for the retailer that for more than a century has sold the trappings of a luxurious lifestyle to Texans of means.

The staff in the film talk up the life-affirming virtues of sable coats and diamond bracelets costing more than $100,000 in today’s money. During one early scene, a manager in the women’s fashions department assembles her team before the store has opened for the day. “In order to feel good, you have to exercise,” she says. “And the things that are most important for us here are our hands—so we can punch the tickets in the cash register—and smiles. So everybody get up, and we’ll do some exercise.”

The roughly dozen women stand and begin repeatedly folding and unfolding individual fingers, and then their entire palms, in time with a dance-beat mix of Rimsky-Korsakov’s “Flight of the Bumblebee.” They move on to extending and retracting their arms above their heads before turning to neck rolls accompanied by a bit of Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. They finish by lifting their faces into smiles over and over. “Now y’all have to permanently smile,” the manager pronounces as the brief session ends.

Luxury specialty stores—like Neiman Marcus, its sister brand Bergdorf Goodman, and its rival Saks Fifth Avenue—don’t build their reputations by driving customer traffic en masse via deals or discounts. They rely, to a far greater degree than mid-priced department stores like Macy’s or Nordstrom, on the personal touch that their armies of sales associates bring to their clientele, reaching out to offer them items they want before they’ve even realized they want them. Just a tad over 37 years after Wiseman’s study of Neiman Marcus, that model hasn’t changed very much, even if somewhat more advanced tools have been deployed alongside the cash registers and smiles.

On a relatively quiet Wednesday afternoon in January, Teri Hardin, general manager of the Neiman Marcus store in Dallas’s NorthPark Center, showed me some of what’s now at her team’s disposal. Since 2013, the sales associates have been armed with smartphones on which a proprietary application called iSell, developed by the company’s in-house Innovation Lab, provides them the sort of information about their customers that they previously had to haul around in thick binders or print out on register receipts.

Dressed in an animal-print jacket over a black top, Hardin pulled out her phone and hunched slightly over it. She remarked that it’s a body position she often sees her own staff assume when they’re not attending to shoppers, sometimes making it difficult to know who’s making use of iSell and who’s merely lost in their own social media feeds. “If a customer came in February, bought a skirt and a jacket and a sweater, and then in April says, ‘I really need another piece to go with that,’ the associate can go and look at the purchase history in the app so they can round out the sale,” she explained. The app also sends salespeople alerts about customers’ birthdays and anniversaries, or about in-store events that might interest them.

The need for such proactive relationship-building with regular customers has only intensified as competition, particularly from online outlets and upscale fashion brands that increasingly sell directly to consumers, has increased during the last two decades. Less and less business filters passively and casually into the stores.

“The customers are smarter,” said Hardin, whose forty-year career has also included management roles at Saks and Bloomingdale’s. “It’s not that they weren’t smart before, but now they’re more educated about what they’re looking for. There used to be more leisure shoppers than there are now.”

These are problems that are far from unique to Neiman’s. Americans increasingly have embraced the ease of buying on their laptops or phones, without having to leave their homes or even get out of their pajamas. Shopping centers across the country have hollowed out with the mass closings of legacy anchor stores like Sears and JCPenney. Sales at department stores nationwide have plunged nearly 40 percent since their peak in 2000. Meanwhile, e-commerce sales have increased by more than 2,000 percent (though, it should be noted, e-commerce still accounts for just about 11 percent of all retail sales, including grocery stores).

One of their most powerful strategies for tackling the future was something straight out of the past.

Purveyors of high-end fashion haven’t been immune to these trends, as evidenced by the demise of Barneys New York last fall. Those who work the Neiman’s sales floors therefore must arm themselves with even more and better information in an attempt to keep up. When company executives opened their doors to me in recent months to discuss their plans for transforming Neiman’s, they were working to roll out a next-generation app they said would provide salespeople even more data and technological tools. They expressed confidence that these digital-age efforts would improve the ease and profitability of each sale.

Yet, at the very time that they trotted out shiny new pieces of technology and angled to boost online sales, one of their most powerful strategies for tackling the future was something straight out of the past. As shopping has migrated online, customers have gained convenience but lost some of the magic; there’s nothing fun about clicking a virtual “buy now” button. Brick-and-mortar shopping, at its best, used to be an experience, and no retailer better represented that than Neiman Marcus. The company arguably invented the concept of experiential shopping—of pampering its customers in dazzling spaces. Reestablishing that as a priority today could help set Neiman’s apart again.

All the while, however, a far more consequential threat to the company’s survival has loomed over every decision executives have made. In 2013, the private equity firm Ares Management, along with the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, acquired the Neiman Marcus Group (comprising Neiman’s itself, its Last Call outlets, and Bergdorf) for $6 billion in a heavily leveraged buyout that saddled the company with debt—$4.8 billion of it today.

In 2018, the Toys “R” Us chain died for just such reasons—not because of the poor performance of its stores, but because it couldn’t contend with the crushing debt it carried due to its acquisition by private equity. Neiman Marcus’s massive obligation likewise meant the company’s survival wasn’t assured merely by keeping its stores in the black. Even tidy quarterly profits might not do the trick. There were regular interest payments to keep up with, too, not to mention the need for additional cash to support investments necessary to better compete in the digital age.

The billions that Neiman Marcus owes are set to come due beginning in 2023. By then, the company has to either scrape together the money to pay off the debt or increase revenue at least enough to persuade creditors to refinance (something they’ve already done once). Still, in his public pronouncements as recently as March, CEO Geoffroy van Raemdonck expressed confidence the company’s cash on hand and generally steady revenue would be sufficient to right the ship, the job he was hired to do in 2018.

That was, of course, before a global pandemic changed everything. Following weeks during which all of its stores were shuttered in the interest of social distancing, late April brought the inevitable news that the company would at last succumb to what it had been struggling to avoid—bankruptcy.

There’s no doubt now that the Neiman Marcus we’ve known for 113 years will be forever changed. Neiman’s was born at a time when the people of Texas rarely had access to the clothing popular in New York and Paris and other fashion capitals. In an age when consumers have myriad outlets for buying fancy clothes and accessories, it’s legitimate to ask: If Neiman Marcus were no more, would it even matter?

On the Friday before last Christmas, the nine-story building at the corner of Main and Ervay streets in downtown Dallas that has housed the Neiman Marcus flagship since 1914 was decked out for the season. The theme for the store’s traditional holiday window display was the circus. In one window, a gorilla statue stood next to an evening-gown-clad mannequin amid a host of sparkling silver and gray ornaments. In another, a red elephant and a yellow bear assisted a pair of mannequins in decorating the same tree the store’s been putting up each year since 1937.

Inside, a line of child-toting parents snaked past shelves of Saint Laurent and Givenchy handbags, a Moët & Chandon champagne vending machine, and temporary displays of stocking stuffers like a musical candy box made to look like an eighties Nintendo video-game console. Each family awaited a turn to visit with Santa.

Six floors above, in his executive suite office, van Raemdonck exuded similar holiday cheer. He and Katie Mullen, the company’s chief innovation officer in charge of developing those whiz-bang new digital tools for associates, sat beside each other on a couch. They were each dressed smartly, but casually. The plaid collar of a button-down peeked out from under van Raemdonck’s dark gray sweater, which he wore over dark green pants and gray sneakers. Mullen wore a lacy black sweater over gray jeans and a pair of black ankle boots.

Van Raemdonck hired Mullen away from Boston Consulting Group, where he got his own start in business, in 2018. Neiman Marcus had been one of her clients for several years before that. The pair told me they’d been tracking holiday sales on an hourly basis, and van Raemdonck grinned sheepishly as he held up a napkin on which he’d scribbled notes outlining his strategy for the company’s stores.

“The future for us is about how do we become what I call a luxury customer platform, being the place where you as a customer come to us because we’re going to delight you in any of your luxury needs,” he said. Yes, that’s how he talks. Many of his sentences flow from business jargon like “tranches” and “capital structure” straight into speaking of his customers as if they’re lovers to be seduced. His hard-to-place accent—he’s from Rixensart, Belgium—imbues nearly everything he says with an air of elegance.

Standing six-foot-three, the 46-year-old has the strong, photogenic features and trim build of a matinee idol. Dallas-based PaperCity published an article on the extravagant, seaside party Van Raemdonck and his husband, interior designer Alvise Orsini, hosted to celebrate their nuptials in the picturesque Italian coastal village of Positano in 2016. “The showstopper was surely Grammy Award–winning soprano Sumi Jo, who floated toward the beach like a Madonna carried in procession on a boat, singing live arias to serenade the happy couple,” the society magazine wrote.

Van Raemdonck began his career as a business consultant specializing in the retail and consumer goods sectors for Boston Consulting before joining L Brands, the company that then operated Victoria’s Secret, Express, and the Limited, among other stores. Following executive-level roles with fashion houses Louis Vuitton and St. John Knits, he was a European group president for Ralph Lauren—which is where he was when the Neiman Marcus Group came calling in February 2018. His work at various levels of corporate management makes for a markedly different résumé than that of Stanley Marcus, the Dallas native who spent nearly his entire career in retail and built Neiman Marcus into one of the nation’s luxury leaders.

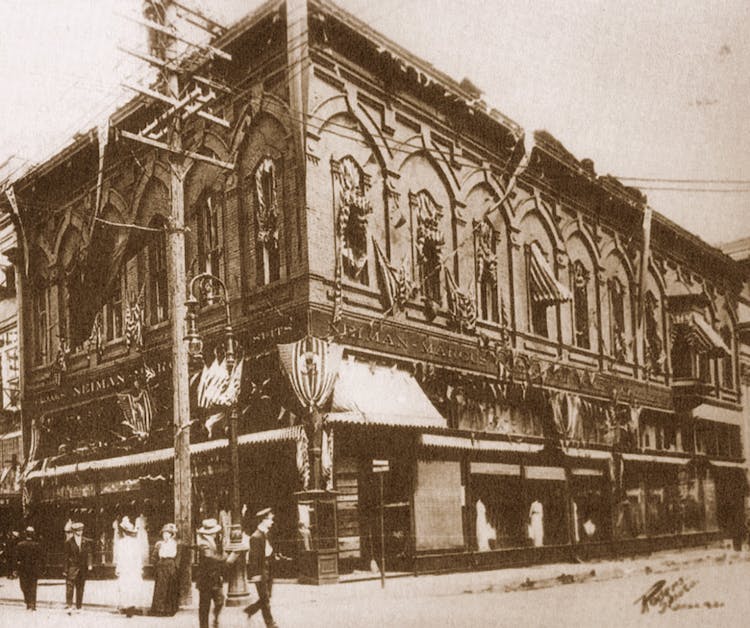

“Neiman’s” is the usual shorthand, but it’s the Marcus family who ran the place for decades. The first shop was opened in 1907 in downtown Dallas by Herbert Marcus, his sister Carrie, and her husband Al Neiman. A full-page advertisement in the Dallas Morning News announced “the opening of the New and Exclusive Shopping Place for Fashionable Women, devoted to the selling of Ready-to-Wear Apparel.” (The men’s department didn’t debut for another couple of decades.)

Al Neiman and Carrie Marcus Neiman divorced in 1928—a result of Al’s infidelity—and the Marcuses bought Neiman out. By then, Herbert’s eldest son, Stanley, had joined the family business. Stanley’s innovations sought to establish Dallas as an unlikely capital of couture. His creation of the Neiman Marcus Award for Distinguished Service in the Field of Fashion lured the likes of Coco Chanel and Yves Saint Laurent to visit Texas. He also worked to whet the aspirational appetites of customers (while garnering plenty of free press) by introducing outrageous fantasy gifts—a custom suit of armor, a $100,000 chicken coop, his-and-hers submarines—to the company’s annual holiday catalog, known as the Christmas Book.

In his 1974 memoir, Minding the Store, Stanley described the Neiman’s formula for success, which he learned from his father. “There was a right customer for every piece of merchandise, and that part of a merchant’s job was not only to bring the two together, but also to prevent the customer from making the wrong choice,” he wrote. “I consider it a doctrine of idealistic pragmatism.”

“They were people who had made their money in a hurry, and they were in an equal hurry to spend it.”

Neiman’s also got a big assist from the discovery of oil in Texas, which spawned “a new breed of customer. They were people who had made their money in a hurry, and they were in an equal hurry to spend it on some of the luxuries they had heard about all their lives,” Stanley wrote.

By 1968, Neiman Marcus was operating four stores, all of them in Texas. Stanley determined that the company needed a larger partner capable of funding a national expansion. He and the board of directors settled upon a merger with the West Coast department store operator Broadway-Hale that largely left the Marcus family in control of Neiman’s operations. Stanley decided to retire from the company in 1975, retaining the title of chairman emeritus.

The combined company fended off a pair of hostile takeover attempts during the eighties with investment from the General Cinema movie theater chain. Ultimately this resulted in the spinoff of a publicly traded corporation, the Neiman Marcus Group, which included both the Neiman’s and Bergdorf Goodman stores. In 1988, General Cinema installed a new chief executive, Allen Questrom, who had run the parent company of Bloomingdale’s and Foley’s. He replaced Richard Marcus, Stanley’s son. The move marked the end of the Marcus family’s reign over the company it had founded.

Yet the legacy of “Mr. Stanley,” as he affectionately came to be known in Dallas, continues to loom large at Neiman Marcus, even though it’s been 45 years since he retired and 18 years since his death. Walk in the entrance nearest the corner of Main and Ervay in the downtown Dallas flagship store, and you’ll encounter a large black-and-white portrait of Marcus, bald and besuited with a salt-and-pepper beard.

He’s a presence upstairs in van Raemdonck’s office as well. A small collection of books on the long console behind the wooden oval table that the CEO uses as a desk includes Minding the Store. Among the images hanging on the office walls are a photo of Stanley Marcus preparing for a runway show and another taken by Stanley’s granddaughter of an impressive collection of suspenders hanging from suit pants in his closet.

Van Raemdonck chose the images to remind himself, he told me, that he’s merely a custodian of a legacy built by others. “Having Stanley in my office was super important because that’s where the formula was created,” he said. “We’re only repeating it and adjusting it to a new age.” That formula, he said, was about forging a “relationship of love” with customers. “The company was created to bring to Texas everything that was most beautiful and unexpected.”

The Neiman Marcus Group returned to private control when TPG Capital and Warburg Pincus bought it for $5.1 billion in 2005. A few years later, the Great Recession was as devastating to Neiman’s as to many retailers, and sales fell off dramatically. Still, the company weathered those times while investing in its discount Last Call outlets and developing its online business. Neiman’s had recovered well enough by 2013 to allow its owners a handsome exit by selling to Ares Management and the CPPIB for $6 billion.

Just prior to Raemdonck taking the reins in 2018, Neiman’s sustained a couple of difficult years financially under then CEO Karen Katz, who’d run the company since 2010. Sales were flagging for many department stores, including Neiman Marcus. The slump was blamed mostly on increasing competition from the likes of both Amazon and upstart fashion e-retailers such as Net-a-Porter and Farfetch. But Katz also pointed to a 2016 plunge in oil prices as adding to the difficulties, since the finances of so many Neiman’s customers in Dallas and Houston—home to the flagship and two of its three largest stores—were closely tied to the fortunes of the oil industry.

Top Neiman’s executives had traditionally been chosen from within the company. Van Raemdonck was very much an outsider.

Top Neiman’s executives had traditionally been chosen from within the company. Dallas native Katz, in fact, had worked herself all the way up to CEO after starting as an assistant store manager in 1985. In contrast, van Raemdonck was very much an outsider. A slight rebound in financial performance during his first year at the helm was followed by decidedly mixed results in his second. There seemed to be no way Neiman Marcus was on track to pay off it billions in debt by late 2020, when it would begin to come due. Bankruptcy appeared a foregone conclusion.

But in March 2019 the company bought itself a little more time. Its creditors agreed to revise the terms of the debt so that it wouldn’t start coming due until 2023. Still, despite van Raemdonck’s insistence that Neiman’s generates sufficient revenue, many analysts suspect that its interest payments have restricted its ability to make investments that the CEO painted to me as vital to significantly growing its business.

One sign that this might be the case was a scale-down of plans for the first Neiman Marcus in New York City, as an anchor tenant in a seven-story mall at the heart of the much-ballyhooed Hudson Yards development, a 28-acre glassy forest of skyscrapers built over a train yard on the west side of Manhattan. Initially announced as a 250,000-square-foot project, the Neiman Marcus at Hudson Yards was 60,000 square feet smaller when it opened in March 2019.

Still, van Raemdonck described his company’s newest location as “the store of the future.” Technology is a greater presence there than at any of the 42 other Neiman’s locations. A mobile point-of-sale system allows customers to pay for merchandise nearly anywhere. Touch-screen digital directories throughout the store enable easy product searches. After downloading an app, shoppers can request songs on a digital jukebox to play over the in-store audio system. Fitting rooms let customers choose from several lighting schemes and feature yet another kind of touch screen, this one for pinging a salesperson to bring in more stuff to try on.

“It’s a massive step forward, and we’re going to test a lot of new ideas,” van Raemdonck said. Each of the new elements was intended as an experiment. Any concepts that yielded significant results could be retrofitted into existing Neiman Marcus stores—though, again, the question was whether the company had the money to do that.

Another characteristic of the Hudson Yards space is more of a throwback. In the early fifties, when Neiman Marcus expanded its downtown Dallas store, Stanley Marcus installed a restaurant on the new sixth floor. He wasn’t the first to do that in a department store—others in the Northeast had begun adding restaurants in the first half of the century—but Stanley’s version, the Zodiac Room, became an unqualified hit. It wasn’t long before the elegant space became the de rigueur dining spot for the city’s ladies who lunch and made Neiman Marcus nearly as well-known for its popovers paired with strawberry butter as for its selection of clothing and accessories downstairs.

In his memoir, Stanley describes the Zodiac Room as something of a loss leader whose value lay in keeping customers in the store as they took a lunch or tea break. Models could also roam the restaurant showing off new fashions. Today the flagship has a small espresso bar and a salon as well. The chain’s second-oldest store, at NorthPark, boasts two restaurants, each with full bars, plus a salon and spa on the lower level.

As Neiman’s expanded nationally, most of its new stores duplicated this model of offering food, spa, and beauty services as a means of making a visit to Neiman’s a full luxurious day rather than a quick shopping trip. Hudson Yards has built upon this approach by devoting even more of its space to “experiences”—a restaurant, a bar, a demonstration kitchen, an event space for fashion shows or parties, plus amenities like skeeball and foosball tables on the men’s floor.

To that mix, they’ve added a corner for the luxury consignment e-commerce platform Fashionphile (Neiman’s bought a minority stake in it last year). Customers can drop off items to be appraised and sold through the website, in one of several pilots the company is running with Fashionphile, including at NorthPark. Similar partnerships could be forged with other businesses—for instance, a luxury travel agency—that target the same income strata as Neiman Marcus.

Marshal Cohen, a retail analyst with the NPD Group and a former Bloomingdale’s merchandise manager, believes this is a smart approach as Neiman’s seeks avenues of growth. “You’ve got to have innovative and impulsive products. By partnering with these secondary markets, it creates a greater level of traffic, and traffic brings impulse,” he says. In other words, these new services can attract customers who might not otherwise shop at Neiman’s, and while they’re there, a gorgeous handbag or beautiful coat might catch their eyes.

It’s a strategy that some Neiman’s competitors, like Saks and Nordstrom, are also increasingly adopting in the face of falling revenue and a new generation of online-savvy consumers who don’t typically shop in department stores. Cohen says that as high-end retailers sought to recover from 2008’s economic collapse, they got away from what had made their stores special, in favor of appealing to a broader range of consumers through their own discount outlets.

“The department store model was built on providing for those that want to shop and be entertained. They would come in, and they would dine. They would get their hair done. They would socialize. They were designed for you to get lost in on purpose,” Cohen says. “Over the past decade, that got lost. There was a homogenous, sea-of-sameness mind-set in all the department stores. Even the most luxurious ones were carrying similar products and similar brands. They went the safe route. They went down the margin route rather than the exclusive route.” But, he adds, “Less risk, less reward.”

For more than a century, well-off Texans have come to know Neiman Marcus as the state’s most successful luxury institution, beloved especially because it’s homegrown. When I recently asked a few longtime Neiman’s power shoppers what makes the store unique, their responses indicated my question was as odd to them as if I’d asked why water is wet. It just is.

Kimberly Schlegel Whitman speaks of Neiman’s with a reverence drawn from countless shopping trips with her mother and sisters as she grew up in Dallas. “We would go and have a fun day and go for lunch,” she told me. “It was always just kind of a happy place. Very comfortable, but you know, you felt like you wanted to also be on your best behavior.”

Sisters Erin Duvall and Molly Duvall Thomas tell a similar story of the central place that Neiman’s has occupied in their family. “We grew up going to Neiman’s with our mom on the weekends, and it was a really special thing,” Erin said. “Texas people are very, very proud of our tried-and-true staples. Neiman’s is just such a classic spot.”

Words like “classic” and “staple,” of course, are not usually associated with the fashion vanguard. And it’s hard to visit the downtown flagship without concluding that its business must count heavily on nostalgia among Dallas shoppers. Not only does that sizable portrait of Mr. Stanley greet you at the entrance, but moving about much of the store feels like stepping back into its fifties or sixties heyday. Compared with those in modern stores, many of the ceilings feel low, many of the spaces dark and cramped (especially riding up the escalator).

It’s a difference that’s all the more noticeable if you cross the street to Forty Five Ten, the luxury retailer that relocated from Dallas’s McKinney Avenue in 2016 and is Neiman’s first direct competitor downtown since the old Sanger-Harris shuttered in 1990. Forty Five Ten’s decor is brighter, poppier, edgier, and its interior staircase tickles the senses with views of product in every direction. Visiting the stores back-to-back, it’s easy to worry that Neiman Marcus is being left behind.

And yet, when the COVID-19 crisis descended upon the country, both Neiman’s and Forty Five Ten were forced to close all their stores. Neiman Marcus furloughed its workers, while Forty Five Ten started laying people off. Neiman’s was at least able to continue selling online—albeit at deep-discount prices—while Forty Five Ten shuttered even its e-commerce operation. The point is that it’s not at all clear which is best positioned to reimagine luxury retail—the hipper upstart or the tried-and-true staple. If it weren’t for Neiman’s debt load, at any rate.

Though the company opted last summer to stop publicly disclosing its financials, van Raemdonck insisted to me that every one of its full-price stores (that means all but the Last Call outlets) was performing well financially. In addition, he touted $1.7 billion in annual online sales (including the contributions of Bergdorf Goodman and Mytheresa, the German online retailer Neiman’s bought in 2014), with $1.3 billion of that coming from folks in the United States. “That makes us one of the largest luxury e-commerce player in America,” he told me. “Twenty years ago, we went online when everyone was like, ‘Oh, no, catalog is the way to go. Why would you go online?’”

Indeed, van Raemdonck has the work of his predecessors to thank for the fact that online sales account for about a third of the company’s annual revenue. Katz, who still sits on the board, did some of the hard work—“groveling” is how she has described it—in convincing luxury fashion houses that selling their clothes online wouldn’t dilute the exclusivity of their brands. (Luxury brands were slow to accept the internet as a place to do business, fearing they’d lose control of the way their products were presented and not be able to offer personalized service.) Katz was also in charge when the company formed the Innovation Lab that oversaw the development of tools like the Memory Mirror, which allows customers to record and download videos of in-store beauty tutorials, and the iSell app.

Another of the initiatives that van Raemdonck has championed was likewise in the works before he arrived. In the fall of 2017, Neiman Marcus launched a pilot program in which it hired seven digital personal stylists to work remotely, communicating with customers via text, email, and phone. A small number of frequent online customers were invited to use the service.

A set of software applications provides the digital stylists their customers’ entire purchase histories, store inventories, as well as reminders about those important dates like birthdays and anniversaries. There’s also what van Raemdonck describes as an artificial intelligence tool that predicts what a customer is or isn’t likely to buy, including fully assembled suggested outfits. These predictions are based on a customer’s shopping history at Neiman’s—items purchased, items returned, items declined when they were suggested. On top of that, the tool factors in the behavior of others with similar buying patterns. The entire sales transaction can then take place online, or if the customer would like to meet for a consultation at a Neiman’s location, the stylist can arrange that as well.

It’s all probably an improvement over the old binders of client info—or at least a good online proxy for them. But, van Raemdonck’s description of the tool as “state-of-the-art” aside, it’s doesn’t sound all that different than the sort of algorithm-driven recommendations today’s digital consumers encounter all the time in using Netflix or Amazon.

“A lot of this technology is going around your head to find your nose,” says Sucharita Kodali, a retail analyst with Forrester Research. “There are many easier ways to achieve what you are trying to achieve.” Besides, she says, it’s not like previous technology such as the iSell app has been a salvation for Neiman’s. Why would these new tools prove any different?

Katie Mullen, the chief innovation officer, described the pilot to me as an unqualified success, with the digital stylists leading customers to increase their spending by 80 percent. The company decided to swiftly scale up from seven to 55 stylists and to offer the service to many more customers. The digital stylists live in six cities, including Dallas and Houston, and most have clients throughout the U.S. While most remain remote employees, some of the stylists work out of the Hudson Yards store, where a suite of fitting rooms is reserved for clientele who purchase online but want to have an in-store fitting.

That’s one step toward what Neiman’s executives describe as their goal of making it easier for customers to transition between their online shopping and the physical store. Elizabeth Gleason, the vice president in charge of the digital stylists, says the program also offers an advantage to the retailer as it increasingly competes online with the very fashion houses whose designs it sells. “When you look at our products, the brands carry them themselves. Their businesses are growing doing direct to consumer,” she told me. “So you’ve really got to differentiate yourself with luxury service.”

“In luxury, ultimately with our customers, there’s no limit. We sold, this week, an $850,000 alligator made-to-measure coat.”

The executives said that the stylist program has more than paid for itself via increased sales, and their hope was to eventually expand its availability to virtually any Neiman’s customer. But first the tools that were developed for the digital stylists will be given to all in-store associates, including Teri Hardin’s team.

The value in the digital tools, van Raemdonck explained, is that it relieves sales staff of some of the more tedious aspects of their jobs—manually pulling a look together, for instance—and allows them to focus instead on “romancing” the customer.

“In luxury, ultimately with our customers, there’s no limit. We sold, this week, an $850,000 alligator made-to-measure coat,” he said. “Someone didn’t come to us for that. A sales associate basically said, ‘Do you know that we can make to measure?’ Then, ‘Do you know that they can be in these incredible fabrics like alligator?’ So the whole thing is a romance. That’s where, in luxury, the more we romance, the more we will grow, but also the more you remember us because it’s all about how we make you feel.”

Van Raemdonck was understandably proud of this. If only there were exponentially more demand for $850,000 alligator coats, Neiman’s indeed might have found its path to recovery.

As much as van Raemdonck likes to cloak his plans for the transformation of Neiman Marcus in the language of seduction, much of what he’s undertaken as CEO are the kind of stark, calculating business decisions that you might expect from the sort of hired-gun consultant he once was. He has replaced much of the company’s leadership—who, between them, boasted decades upon decades of institutional knowledge—with recruits from the likes of Apple, Sephora, and Starboard Cruise Services.

Gone is executive vice president Neva Hall, who oversaw the development of about one-third of Neiman Marcus stores during her 35 years with the company—replaced by David Goubert, like van Raemdonck a veteran of Louis Vuitton. Gone is Ken Downing, senior vice president and fashion director, who represented Neiman’s to top designers all over the world for much of his 28 years with the company. Gone is Jim Gold, president and chief merchandising officer, also after 28 years—replaced by Lana Todorovich, like van Raemdonck a veteran of Ralph Lauren. Hall didn’t respond to my request for an interview, while Downing and Gold both declined to speak.

Another key departure has been Scott Emmons, who left in December 2018 after twelve years. He spent the last seven of those heading the Innovation Lab, the department responsible for developing so much of the technology on which Neiman’s has been betting its future. Not long after he left, he penned an op-ed titled “Why I’m Leaving Neiman Marcus” that hinted at where he believes the company has fallen short in its digital transformation.

Emmons discussed corporate managers more interested in creating short-term “PR moments” to garner press attention than in developing technology that could make a true, sustained difference to the company’s bottom line. He also pointed to a lack of buy-in in the use of new technological tools by sales associates, and a dearth of financial backing for these efforts. “It’s one thing to talk about agility and risk, but when you’re not built for either, measured by cost reductions and operating silos, results tend to be only incremental,” Emmons wrote for the influential industry website the Business of Fashion.

“There has to be something magical that’s happening inside those four walls to get people to come.”

In a February interview, Emmons told me he intended the op-ed as a discussion of where all retailers are falling short, not just Neiman Marcus. And while he hinted that “new voices” in the company had different opinions about the role of technology, he doesn’t doubt that van Raemdonck and other new executives believe in its importance as more than a gimmick. “Just having great merchandise at a pretty space is not necessarily enough to get people to go get in the car and drive to a store anymore,” Emmons says. “Absolutely there has to be something magical that’s happening inside those four walls to get people to come.”

Retail analysts agree that Neiman’s is taking the right sorts of steps—like the digital stylist program, the attempts to develop technology that could aid in increasing sales, and the reimagining of it stores as places where a wider (but still selectively upscale) range of services and products are sold. They also agree that specialty retailers like Neiman’s are in a better position to survive in a world of declining business for brick-and-mortar retailers than are lower-cost chains like JCPenney or Sears.

Among those experts is Robert Sakowitz, who ran his family’s Houston-based chain of high-end specialty stores—directly competing with the likes of Neiman Marcus—for nearly thirty years, until the eighties’ Texas oil bust proved to be its undoing. Since 1990, he’s run his own consulting firm, and he outright rejects the notion that the retail industry is failing.

“To the contrary, brick-and-mortar stores aren’t just all dying off. It’s the ones that overexpanded, or it’s the ones who no longer have a reason to exist. The JCPenneys and the Searses of the world don’t have a niche anymore, as opposed to Neiman’s,” he says. “People will always want fine quality. But it’s delivering that fine quality with good service—that’s the challenge of the digital world.”

What Sakowitz and the others questioned is whether any of these measures would make more than a marginal difference or bring about change quickly enough to prevent Neiman’s from being sunk by the weight of its financial burden.

A couple of months after my interview with van Raemdonck and Mullen, a potential new lifeline for the Neiman Marcus Group emerged. The company was looking into taking Mytheresa public. Since late 2018, Neiman’s has been legally tussling with one of its creditors, Marble Ridge Capital, over the hedge fund’s allegations that the retailer had fraudulently shifted Mytheresa outside the reach of creditors, a financial maneuvering that could matter greatly if the company were to lapse into bankruptcy.

Mytheresa has been a relatively strong financial performer in recent years. (It’s probably not a coincidence that it’s an online retailer.) In late 2018, Mytheresa’s ownership was officially transferred from Neiman Marcus to the umbrella parent company Neiman Marcus Group. So, in the case of a bankruptcy, when creditors of Neiman Marcus’s billions in debt come looking to recoup whatever they can of what they’re owed, Mytheresa may well be protected from those claims. The Neiman Marcus Group’s private-equity owners might therefore avoid even greater losses.

Tim Hynes, director of North American research for the credit-market data service Debtwire, told me on the day after news of the potential IPO broke that it could be a saving grace for Neiman Marcus. He pointed to a similar situation last year when debt-laden retailer PetSmart successfully took its e-commerce subsidiary, Chewy, public and used proceeds from the selling of shares to pay down enough debt to greatly improve its finances.

Hynes said that Neiman’s appeared to have enough cash on hand that it wasn’t in imminent danger, but he also estimated—based mostly on how poorly the bond and credit markets were rating the company’s prospects—that without the Mytheresa IPO, Neiman’s would likely face bankruptcy within a year. His analysis made it plain that, for all the digital magic and shiny new spaces that van Raemdonck hyped, all that was really left for the company that Stanley Marcus built were desperate measures.

“So they would want to do the IPO as soon as possible because the markets are still there. The stock market is doing well,” Hynes said in mid-February, before adding, “With this coronavirus thing, it’s down a little but not much. If somehow that spreads to the U.S., it could severely impact the markets.”

His analysis, of course, proved prescient. The Hail Mary public offering is probably off the table. The U.S. economy tanked with the forced temporary closure of so many businesses because of the coronavirus. Even before that occurred, in mid-March Neiman Marcus announced that it was permanently shuttering its discount Last Call chain to focus on its core full-price luxury business. Two of its Texas distribution centers, in Irving and Longview, were to be sold as well. With these moves and other consolidations of in-store and online staffs, about 750 jobs were eliminated. The desperate measures had begun.

The next week, Neiman Marcus temporarily closed all its stores as most of its customers were sheltering in place to avoid infection. Then, at the end of March, it furloughed many of its 14,000 employees through at least April 30 and cut the salaries of those remaining on the payroll, including van Raemdonck, who waived 100 percent of his pay for the month. Soon after, news emerged that the company was exploring what it had so long hoped to avoid—bankruptcy protection. Then it reportedly missed a mid-April interest payment on its debt.

Bankruptcy isn’t a synonym for going out of business. It’s a process by which a company admits it has no viable path to paying off its debts and seeks to work out deals with creditors while also being relieved of some of those obligations. It likely means selling off many assets and permanently shuttering some stores. It likely means a much, much smaller Neiman Marcus, but that could also mean a Neiman’s with less debt that’s better able to turn more of its profits into investments toward building the sort of bright, digitally driven future to which van Raemdonck has aspired.

It might have been better for Neiman Marcus to have done this sooner, filing for bankruptcy before it found itself in the midst of global crisis during which it’s anybody’s guess when retail stores will do anything like normal business again. It might have been better for Neiman Marcus, but it wouldn’t have been good for the chain’s owners, for whom bankruptcy probably means writing off hope of recouping their investment.

Neiman’s deserves better than its owners have done by it. Yes, department stores and the retail sector as a whole have fared poorly in recent years. But Neiman Marcus’s problem wasn’t that it had no clue how to turn a profit on its stores, even if some of its experiments end up flopping. Its problem wasn’t a lack of adoring customers, either. Its problem was a single poorly timed and ill-conceived financial transaction that hamstrung its every move from then on.

Bankruptcy likely doesn’t mean the end of Neiman Marcus, at least in some form. Its brand-name alone is probably too valuable for that. But if Neiman’s winds up a husk of its former self, even Mr. Stanley might ask to have his portrait removed.

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated the increase in e-commerce sales since nationwide department store sales peaked. It also misstated the year of that peak, as well as the percentage of all retail sales accounted for by e-commerce.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- Business

- Longreads

- Fashion

- Dallas