When T. Boone Pickens graduated with a geology degree from Oklahoma State, in 1951, his father, Thomas Boone Pickens, told him that “a fool with a plan beats a genius with no plan every time. My problem is, you’re no genius, and you got no plan.”

As it turned out, the elder Mr. Pickens was wrong. His son, the famed oilman and corporate raider who died today at the age of 91, was, in fact, a genius of sorts.

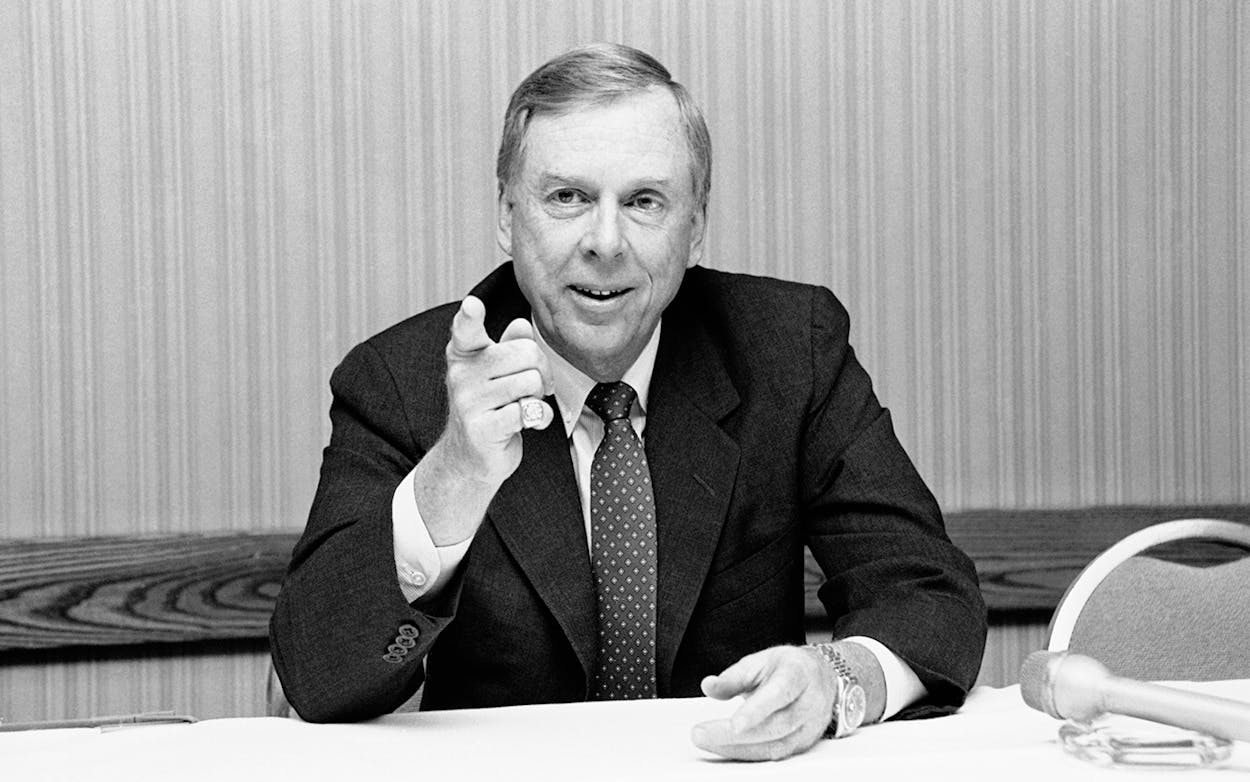

In the spring of 2016 I stopped by Pickens’s Dallas office to interview him for a book I was writing. Pickens was 87, and his hearing was going, but his mind was sharp. Our conversation meandered, and at one point we started talking about the fate of the grand Texas ranches. I said something about the Matador, and Pickens stopped me. “The Matador, they have about 130,000 acres, I believe,” he said. I had no clue if he was right, but Jay Rosser, his longtime chief of staff, googled it, and, sure enough, the Matador had exactly 130,000 acres.

It was classic Pickens. He stored numbers in his head like a squirrel stores nuts for the winter; if you asked him about commodities markets, he could immediately tell you how much oil the U.S. had produced the day before and how much the Saudis cranked out last week.

Read Skip Hollandsworth’s September 2008 cover story on T. Boone Pickens.

As for plans—well, Pickens had no shortage of those, either, though it took him a while to land on one. As his father feared, young Pickens wasn’t sure at first what to do with himself. After graduation he started working for Phillips Petroleum, where his father was employed as a lawyer. But he quickly came to disdain the corporate world, an attitude that would hold him in good stead decades later. Within a few years, he struck out on his own.

Pickens’s life as an independent oilman didn’t start out glamorously. He rattled around the dusty plains of West Texas in a 1955 Ford station wagon, consulting at well sites for $75 a day. He often slept in his car and shaved at gas stations.

Nevertheless, he managed to get a few investors behind him to form a company that eventually became known as Mesa Petroleum. In the seventies he started making a name for himself by perfecting the concept of a royalty trust, turning an idea that had been used for liquidating assets into a vehicle that would pay returns to oil and gas investors with significantly reduced tax obligations.

But his greatest fame—and infamy—came during the eighties, when he noticed a new source of reserves: the balance sheets of oil companies whose stock prices were depressed due to mismanagement of their assets. Pickens believed he could do a better job of managing those assets. He just needed to get his hands on them.

By 1982 he’d identified his first target: Cities Service Co., a Tulsa company six times the size of Mesa Petroleum. “Cities Service was a case study in what was wrong with Big Oil’s management,” Pickens wrote in his 1987 autobiography, Boone. The company’s refineries and chemical plants were losing money, and its oil and gas reserves had been declining for a decade. Pickens was primarily interested in the reserves, which he could add to Mesa’s, but the idea that a smaller company would buy a larger one seemed outlandish. Guppies didn’t swallow whales.

In this case, the guppy’s eyes were bigger than its stomach. Rather than submit to Mesa, Cities decided to sell itself to Gulf Oil Co.—though Mesa made a tidy $30 million profit on the transaction. (Gulf later withdrew its offer, and Occidental Petroleum Corporation eventually closed the deal.)

Pickens spent much of the decade pursuing other oil companies, including Gulf, whose executives often accused him of threatening a takeover just so they’d pay him a high price to buy back his stock and make him go away, a process known as greenmail. “I was seen as the financial barbarian with little regard for shareholders, employees or consumers,” Pickens wrote.

A Time magazine cover story in 1985 likened him to Dallas’s J. R. Ewing. “To his victims, mostly entrenched corporate executives, he is a dangerous upstart, a sneaky poker player, a veritable rattlesnake in the woodpile,” the magazine wrote. “To his fans, he is a modern David, a champion of the little guy who can take on the Goliaths of Big Oil and more often than not gives them a costly whupping.”

And plenty of Davids benefited from his battles. Pickens turned the takeover game into the shareholder rights movement, arguing that companies have a responsibility to their true owners, the stockholders, whose interests were often overlooked by corporate boards. The activism that he helped ignite has generated untold billions—perhaps trillions—for investors. And since this push coincided with the rise of 401(k) plans and an influx of small investors into the market, chances are that somewhere in your retirement portfolio, there’s at least one stock whose returns have been improved by investor activism. (It should be noted that the shareholder rights movement had its downsides; plenty of employees were laid off as a result of corporate raids, and the need to increase share prices led to financial scandals and declining emphasis on long-term business goals.)

Pickens was one of the world’s few remaining self-made oil billionaires, a rough-and-tumble breed that took huge risks and won big and lost big. As an oilman he did both. In the nineties, weak natural gas prices forced him to give up Mesa to Fort Worth billionaire Richard Rainwater, and many oil executives saw it as Pickens’s comeuppance. “I never found much oil,” he told me during that visit in 2016. “I probably had no more than five really great years. It’s a competitive, risky business every day.” Every time he thought he made money drilling, he would wind up losing it investing in new prospects to replace his reserves.

But after his 1990s debacle, Pickens started over, building a hedge fund that invested in oil and gas futures, and in 2000 he spotted early signs that natural gas prices were poised to rise. They shot from less than $2 to more than $13 per thousand cubic feet by 2003, making Pickens a billionaire in his mid-seventies.

It was then, at the height of his financial success, that the politically conservative oilman—he was one of the financers of the much-criticized “Swift Boat” ads that smeared John Kerry’s war record and helped sink his 2004 presidential candidacy—became an unlikely champion of renewable energy. In 2008 he unveiled his “Pickens Plan” (perhaps he was once again trying to prove his father wrong) to wean America off foreign oil by encouraging the country to turn to his favorite commodity, natural gas, as well as solar and wind energy. (Skeptics of his sudden interest in clean energy pointed out that he was planning to develop a major wind farm on his 65,000-acre Panhandle ranch.) He was lauded by former vice president Al Gore and the executive director of the Sierra Club and, thanks to his prolific use of social media, became an unlikely internet sensation. A younger generation who knew little of the takeover battles of the eighties loved the story of an old-school oil guy embracing renewable energy. To this day, he has millions of followers on social media.

But by 2010 he had backed away from renewables and decided to focus on natural gas; he later urged federal subsidies for natural gas-powered trucks. Sometimes, even a genius with a plan doesn’t prevail.

Three years ago, during a trial over oil and gas rights in the Permian Basin, Pickens suffered the first of a series of strokes. After that, his mind was not quite as sharp, and speech was hard for him. In March 2018, I traveled with him to his Mesa Vista Ranch in the Panhandle, near Pampa. It had been his refuge since the early seventies, but he had decided to sell it. A sense of melancholy hung over the weekend.

At one point during a tour of the ranch, we stopped at his childhood home, which had been transplanted from Holdenville, Oklahoma. As he sat in the living room, his mind seemed to clear. He told stories of his youth, pointing to the first plate he’d eaten from as a toddler, positioned on a wooden rack on the wall just as it had been when his mother was preparing meals.

Pickens, like many wealthy people of humble beginnings, was a contradiction. Once, as he and I traveled to New York on a private jet and a chauffeured black Cadillac Escalade, he professed that he was really just an “aw-shucks” guy. An aw-shucks guy, that is, who built a $50 million house for his fourth wife with a front door that had once belonged to Bing Crosby.

But in a way he was right. His greatest accomplishment as a businessman wasn’t the hundreds of millions of dollars he made (and lost) over the decades. It was his insistence on reminding out-of-touch corporate executives that it was their stockholders who actually owned their companies. That seems like a fitting legacy for an aw-shucks billionaire.

- More About:

- Business

- Obituaries

- T Boone Pickens

- Dallas