Brian “Sunny” Sunblade found himself face down on the ground in downtown San Antonio surrounded by cops on June 2. The black 24-year-old construction worker says his hands were cuffed behind his back, his legs were hoisted into the air, and an officer pressed a knee onto his head.

Sunblade’s crime? Crossing against a pedestrian control sign, then resisting arrest. He says he wasn’t involved in a demonstration that was going on nearby, and was just out to survey several days of damage—shattered glass, boarded-up windows, graffiti—from prior demonstrations with his neighbor and friend, Priscilla Gonzalez. As they walked, Sunblade went to check out whether the Whataburger across the street was open. A group of officers near the door called out and told him not to cross in the middle of the street. But he was hungry, the street was empty, and he couldn’t see the harm.

According to the police report, Sunblade walked to a crosswalk but disregarded the pedestrian control sign when crossing. Immediately, several of the cops surrounded him, and Sunblade allegedly refused to put both hands behind his back to be handcuffed. Officers report subsequently “taking [him] to the ground”; he says he was pushed. Gonzalez, 27, started running toward Sunblade, yelling at the officers that he hadn’t done anything wrong. Officers arrested her, too, for being a pedestrian in a roadway. As police put her in handcuffs, Gonzalez looked over at Sunblade. The image, she says, was all too familiar: a black man pinned to the ground by an officer’s knee.

“It was just brutal, excessive force for him crossing the street,” Gonzales later said.

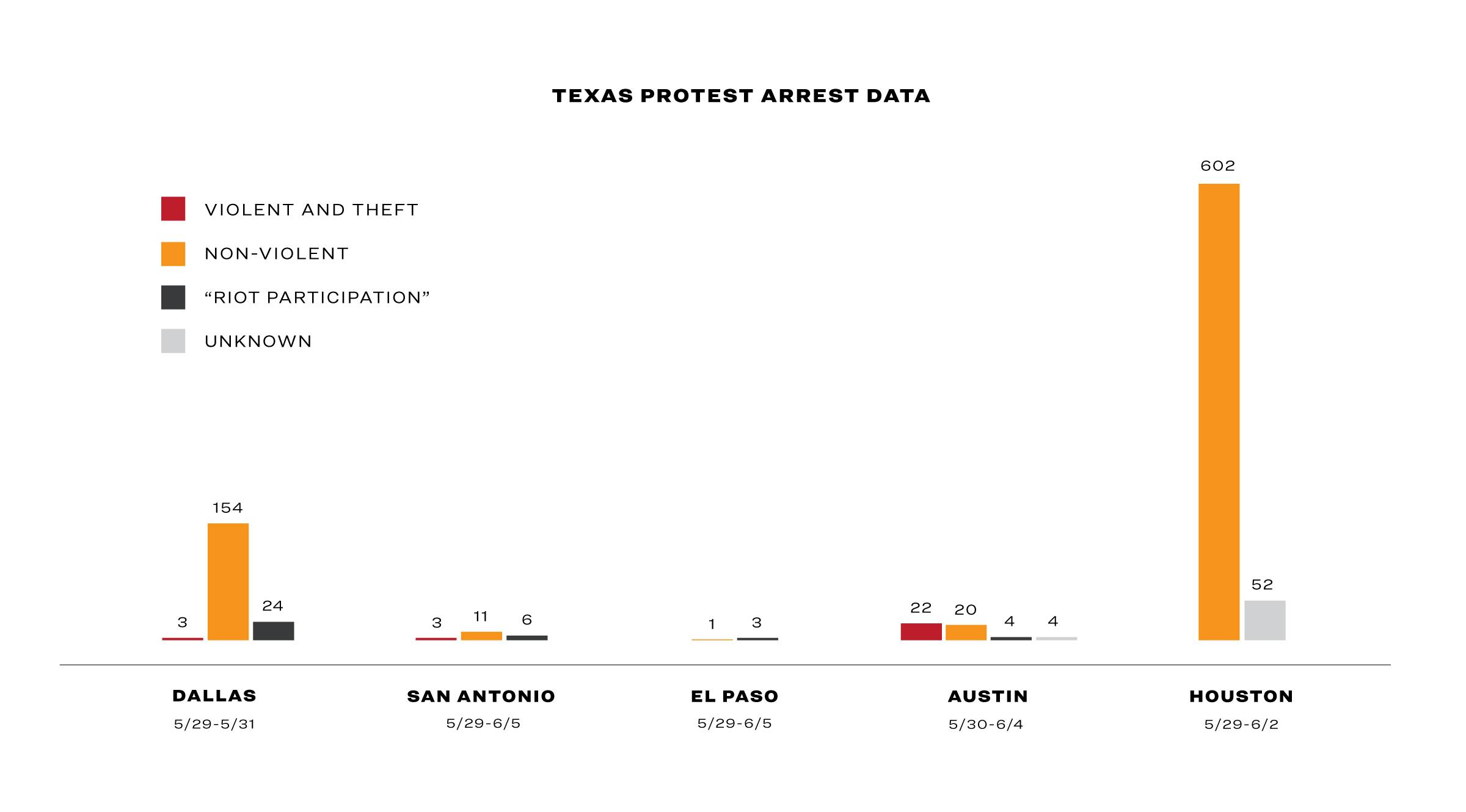

Sunblade and Gonzalez were two of nearly one thousand people in four of Texas’s largest cities arrested during the first week of protests following the police killing of George Floyd—the majority of whom were charged with nonviolent crimes. Arrest data from Dallas, San Antonio, Austin, and El Paso indicates that most of these arrests were for low-level offenses, including violation of curfew and blocking traffic, and not related to violence, theft, and destruction of property. A number of protesters were also charged with “riot participation,” a charge legal experts believe was unfairly brought against peaceful demonstrators.

In Dallas, 85 percent of the 181 protest arrests made from May 29 to May 31, the first weekend of protests, were for violating curfew, obstructing roadways, evading arrest, or disorderly conduct. In several cases the last charge meant “traveling with a large crowd and refusing officers’ commands to disperse” and “inciting breach of the peace at protest,” according to a Dallas Police Department spokeswoman.

Dallas police dropped misdemeanor charges against an additional 674 protesters arrested on June 1 for obstructing a highway. In announcing the dropped charges, Dallas police chief Reneé Hall said she stood by the initial arrests. Dallas city manager T.C. Broadnax applauded Hall’s decision to drop the charges, saying that “Now is the time for collaboration and compassion not confrontation.”

In San Antonio, where police made twenty arrests for protest-related offenses during the first week of demonstrations, 55 percent were for similar violations. In Austin, where 50 were arrested, 40 percent were for low-level violations. And of four demonstrators arrested in relation to protests in El Paso, one was charged with being a pedestrian in the roadway and three with “riot participation.”

The Houston Police Department has not yet fulfilled records requests filed by Texas Monthly that would provide details on the more than 650 arrests it made during the first week of protests. But Harris County district attorney Kim Ogg dropped charges June 10 against 602 protesters, most for obstructing a highway and trespassing. Ogg is still pursuing charges against 51 adults and one juvenile accused in 35 misdemeanors and 19 felonies, including “weapons offenses and aggravated assault of a peace officer,” according to the DA’s office.

Fort Worth police also dropped charges against about fifty protesters arrested for rioting.

Among the four cities that fulfilled records requests, 37 demonstrators were charged with “riot participation” during the first week of protests. The Texas Penal Code defines a riot as a group of seven or more that endangers property or people, obstructs law enforcement or government functions, or deprives a person of his or her legal rights by force or threat of force. But across the four cities, many of those involved in looting and destruction of property were charged with burglary and criminal mischief, not riot participation, leaving others to question the validity of the “riot” charges.

Jasmine Crockett, an attorney representing many of those arrested in the Dallas protests, said her clients’ actions don’t fit the legal definition of “riot participation,” and amount to little more than participation in the protests. She added that in more than a decade of practice, she hasn’t seen the statute used against protesters, who are more typically charged with obstruction of roadways. “It’s like they just randomly threw something on them,” Crockett said, adding that the protesters she’s representing pro bono have submitted video evidence of their involvement, and remained peaceful.

Andy Chatham, a former state district judge in Dallas, said that to proceed with these cases, prosecuting attorneys would have to prove that each protester arrested for riot participation harmed or damaged a person or property or encouraged others to do so, which would be difficult to do considering the large group of demonstrators present.

“Simply being next to someone who decides that this is going to turn into a riot when it starts out peacefully doesn’t make you a rioter,” Chatham said. “And I know that’s what happened here.”

The police in Dallas, Chatham said, rounded up protesters and then searched for something to charge them with—and county officials have now determined to drop some of those riot charges. “Then the smart people over at the DA’s office [in Dallas County] … looked at this and said, ‘I’m not filing against these people for that. That wasn’t what they were doing.’”

Unlike in other cities, the arrests in Austin reflect more of the burglaries and property damage that occurred there. Of the fifty arrests the first week of protests, five were charges for trying to rob an ATM, and thirteen for burglaries, including at a Sam’s Club, Target, Foot Locker, Walmart, and a pawn shop. Other arrests stemmed from police searches of “suspicious” vehicles. Officers patrolled areas around shopping centers on May 31 after seeing chatter on social media indicating that the stores might be targets of theft. In two separate incidents, officers saw a car pass by and decided to pull it over. Drivers were subsequently arrested for weapons offenses and marijuana possession.

On May 31, “in response to the ongoing threats of violence and looting,” Governor Greg Abbott declared a state of disaster after the first weekend of protests in Texas and activated the Texas National Guard. The next day, Abbott released a statement suggesting that agitators could be coming from out of state to “hijack” local protests.

Abbott added that he was working with four U.S. attorneys in the state to ensure protesters coming across state lines to incite violence would be federally prosecuted. The governor’s office did not respond to requests for interviews on whether or not any federal charges have been filed related to out-of-state protesters.

Data suggests most of those arrested during the first week of protests were Texans. None of those arrested in San Antonio or El Paso were from out of state. In Houston, a local ABC affiliate found that fewer than 2 percent of those arrested during the first weekend of protests in the city were from out of state. Residential data for those arrested in Austin was not available.

Dallas records indicate eight of the 181 arrestees were from out-of-state, but three have Texas driver’s licenses. A fourth was identified by the Dallas Police Department as being from Louisiana, but Dallas County court records list his residence as Garland, Texas.

Of the remaining four, three—arrested for curfew, pedestrian, and disorderly conduct violations—could not be reached for interviews. The fourth, Mark Buckley of Charlotte, North Carolina, was in the Dallas area visiting a friend in McKinney. After seeing that police had used tear gas and pepper-spray pellets on protesters the night before, Buckley and a friend loaded up on water, Gatorade, snacks, and gauze at Walmart and went downtown to hand them out to protesters on Sunday.

A few hours later, they were packing up their van, which was parked in a parking lot, when officers approached the vehicle and pulled them out of it. Buckley, 26, was arrested and charged for being a pedestrian in the roadway.

Some of those arrested across the state expressed feeling emboldened by their experiences with police to keep participating in protests. Now back in Charlotte, Buckley continues to provide food and water to demonstrators there. In San Antonio, Sunblade and Gonzalez are still waiting to hear if the charges against them will be dropped. Gonzalez says she’s started tuning into city council meetings so she’ll be better prepared to continue fighting for police reform.

In Austin, Chloe Frangenberg, a 22-year-old nursing school graduate, was similarly roused by her arrest. Frangenberg was protesting on I-35 on May 30 when officers told the group she was in to move or face arrest.

“I stood my ground,” Frangenberg said. “The officer I had been facing then yelled, ‘Get her,’ and I was slammed to the ground and arrested.”

She was detained for about twelve hours, then notified around 1 a.m. that a judge had waived the charges against her and the others she was arrested with.

It was Frangenberg’s first protest, but the way she saw police treat her and others lit a fire under her. She attended another protest the weekend of her birthday.

“I won’t stop,” she said. “It did the opposite of what the cops wanted. It made the fight in me even greater.”

- More About:

- Black Lives Matter

- Greg Abbott

- George Floyd