On May 25, a Minneapolis police officer kneeled on George Floyd’s neck for nearly nine minutes, killing him on camera. Every night since then, protesters have taken to the streets to call for justice for Floyd, and for far too many other black people who have been shot and killed by cops. In city after city, in all fifty states, protesters have been tear-gassed and surrounded by police in riot gear, prompting even larger crowds the next day. Many Texans are now speaking out against police brutality for the first time, but the fight to reform police departments isn’t new.

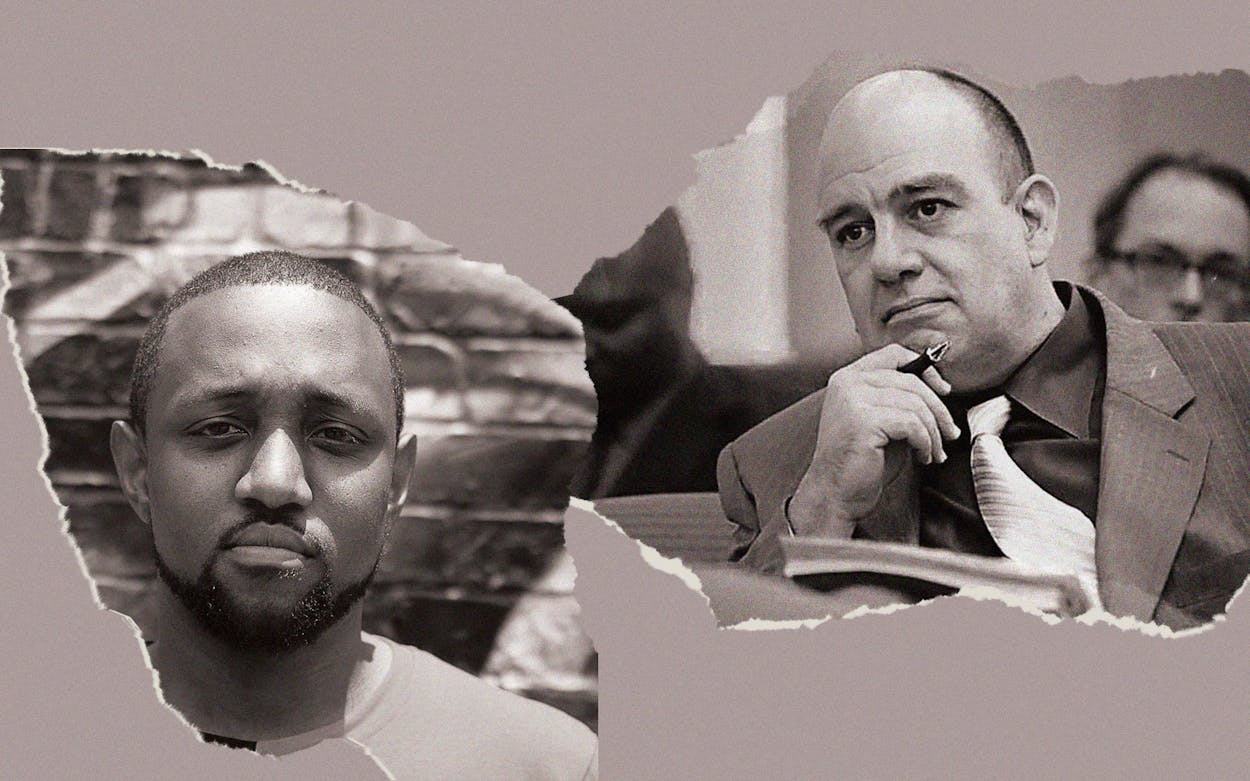

Scott Henson has been working in Texas’s criminal justice reform sphere for two decades, chronicling every angle of it on his blog, Grits for Breakfast, since 2004. A former journalist and political consultant, he also served as the executive director of the Innocence Project of Texas and the ACLU of Texas’s Police Accountability Project.

Chas Moore is the founder and executive director of the Austin Justice Coalition, which had initially planned the protests last Sunday in Austin. Moore ultimately decided to cancel the event after protests on Saturday resulted in civilian injuries. In April, after an Austin police officer shot and killed an unarmed man named Mike Ramos, the coalition joined several grassroots organizations in calling for the firing of police chief Brian Manley. They also helped push the City of Austin to negotiate a new contract with the police union that included important wins for transparency.

Henson and Moore have been working together on criminal justice reform and accountability since 2015. Texas Monthly spoke with them about the recent protests, why police reform is harder than it seems, and what the media gets wrong when reporting on the police.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Texas Monthly: Were either of you surprised to see the images from this weekend, when it seems that the cops were being pretty confrontational toward protesters?

Scott Henson: Not me. That’s par for the course.

Chas Moore: I agree. I think it would be very naive to assume that [the cops] would actually understand why people were out there and that they would change overnight, or over seventy-two hours. Cops are going to be cops.

SH: In fact, the only real difference is that the tactics that are normally reserved for black folks got used on everybody.

TM: Are there certain practices and policies that have led to this moment?

SH: It’s politics. The majority of both parties have had a bipartisan consensus that basically says, “Whatever the police want, the police get.” And that has been for my entire adult lifetime, certainly the last thirty years and going back to Nixon’s war on crime.

The police unions’ political power is a big part of it. Prosecutors are allied with police, so it doesn’t matter if you’re a Democrat or a Republican: if you have that job, you’re not gonna prosecute cops because you have to work with them every day.

CM: There’s a lack of checks and balances when it comes to police accountability. The strength of police departments over a really long period of time has led to police departments, not only in Texas but around the country, being able to run around and do whatever they want. From every part of the criminal legal system, nobody checks them at all.

TM: In the past week, it seems as though there has been more conversation about demilitarization and abolishing or defunding the police, at least on social media. That wasn’t mainstream a few years ago, so what direction do you see that going?

SH: When people say “abolish the police,” what they mean is scaling it back. We have used law enforcement to confront a variety of social issues where it was inappropriate. We’ve used them to confront addiction. We’ve used them to confront homelessness. We’ve used them to confront mental health. These are morally bankrupt and practically failed policies. And so what [people mean by abolition] is taking police out of those situations, reducing their budgets significantly, and shifting that money to social services.

The reality is because we have police doing all this stuff, they’re not doing actual police work that they should be doing well. Clearance rates for murders, for armed robberies, for burglaries are far lower than they should be. You’re hearing the “abolish police” rhetoric, but the agenda is a little more nuanced than that.

CM: I think this is interesting, because I’m one of the people that Scott doesn’t believe exists [laughs]. I think we can get to a world where we don’t need police. You know, when I think about the origins of policing and where we are today, it’s the thing that keeps me going to do this work. So how do we completely get rid of policing the way it is today? I absolutely believe in a world where we don’t have cops killing black people just for the f— of it.

TM: You’ve both expressed frustration with the way things are. Is there space to work within the system right now, or is there a need for a new approach?

CM: This is an ebb and flow. Think of the riots of ’67 that created massive change in ’68. Think of Rodney King, when people were completely fed up with the system, so, “Okay, we go out and rebel.” As they should. But at some point, you know, you have to start going back to work, you have to start taking care of your family and kids. Me personally, I think it’s a lot easier to fix this thing that we got than to just completely start all the way over.

TM: Can you point to any reforms in Texas that have been successful?

SH: To take Austin as an example, you’ve seen city council try to implement reforms that I think are very positive. They have tried to scale back arrests for Class C misdemeanors [low-level offenses]. There’s been attempts to scale back the use of police for mental health calls.

But the police department has fought tooth and nail at every stage, and often has refused to implement those policies. So for example in Austin, they ponied up [millions] in the last budget to install clinicians at the 911 call center to divert mental health calls. In the last six months or so, out of 19,000 mental health calls, they only used the clinicians for like 200 of them. The police department as an institution has basically dug in its heels and refused to implement those policies.

Similarly, quite a few cities have authorized police to use their discretion to issue citations instead of arresting for low-level misdemeanors. The cops simply have not done it. We finally just saw San Marcos, the first city to pass an ordinance saying “You’re not going to have the discretion to issue citations. You will always issue citations in these circumstances.”

So, that’s the fight we’re having. When the local government tries to do something different, tries to scale back the worst abuses or divert the resources to different approaches, the police departments don’t want to do it, and they have enough institutional power to say no, we’re not going to.

CM: For me, the thing that really makes me feel like, “Hey actually, you know, if we keep doing this right … we could probably do something,” was our big fight with the Austin Police Association on the union contracts. I believe to this day, the manner in which we won [by getting a seat at the bargaining table] doesn’t usually happen at all. And freedom cities, the marijuana ordinances are signs of baby steps of progress. But then to have the chief come out and say we’re against the homeless ordinances is also a sign of the institution not understanding that we are trying to get somewhere better, more equitable, and equal. It’s like a two-steps-forward, one-step-back type of thing.

TM: Are there solutions you’d like to see specifically addressing the disproportionate amount of violence that black people experience from the cops?

CM: I don’t know. You can’t “courageous conversations” your way out of racism. You can’t train your way out of being a racist asshole. But there are things we can do that don’t empower the police department so much, so they don’t feel so emboldened to just do whatever they want. Right now, there’s a very serious conversation around the country about defunding police departments. We need to divert funds from police departments and put them to other areas within city budgets, to make sure we can provide those services to communities and people that need them.

The police have so much money, and [public health] is so underfunded. So when COVID happened, they were running around scrambling, looking for solutions, looking for ideas, and that’s why it took so long to get testing in the most immunocompromised communities. Defunding the police is a critical first step, but that’s definitely not going to fix racism and people’s biases against black people.

SH: Trying to expunge racism from society is a far bigger question. I think we can scale back the violence much more easily. Deadly force is a good example. Right now, if someone is suspected of having committed violence, a cop can shoot them. There doesn’t have to be an imminent threat. They don’t have to try and de-escalate in any way. You’re authorized to shoot them. We need to change that statute. The Police Executive Research Forum, the national think tank on law enforcement, came out with resources for de-escalation policies. In Austin they have narrowly put that on the books. They train you to try not to use force but once you start, you go whole hog. Well, that’s not what de-escalation is supposed to be, according to the national best practices.

TM: Another conversation in the public sphere right now is accountability. In the case of Mike Ramos and George Floyd, there were videos, and in Dallas you have the cops saying there are outsiders protesting, but they’ve mostly arrested local people according to public records. If the police department can put out a statement with a lot of leeway on how they frame the issue, what does accountability look like?

CM: I think it goes back to the power of police departments. You can show them they are doing something explicitly wrong. But in their mind it is justified, because this person didn’t comply or didn’t comply fast enough. That cop that was on the neck of George Floyd, he thinks he didn’t do anything wrong. And again, there are no checks and balances. A few years ago was the first time we saw cops getting indicted and going to jail. This whole institution is run amok. [It is] there to protect the system as is. That’s why they get that leeway.

SH: The answer to your question is that journalists who cover law enforcement suck. Across the board. [Journalists] feel like they need [cops] as sources, so they defer over and over. The police union should not be your go-to source on every policy question. If it is not an employment issue, journalists should not be asking the police union their opinion.

In Houston, the union is engaging in outright demagoguery on bail reform, telling lie after lie on what is going on. That’s our biggest barrier to change: journalists deciding to do their damn job and stop kissing the police union’s ass and giving them undue influence would solve half of that problem when it comes to accountability to the public. I call that laziness but if you’re being generous, it’s the constraints of journalism in this era. Most newsrooms have seen cuts, and there are fewer journalists covering more stuff. So you’re going to do what’s easy: calling the police union and getting a quote and running that. What’s hard is filing open records requests and speaking to advocates, defense lawyers, judges, or other people who have insight into what’s going on and getting a more nuanced view.

The other piece of accountability is about internal disciplinary processes, and prosecutors holding [officers] accountable. There’s tension between police unions and police departments. The state civil service code has protections to keep officers from being held accountable. The police unions got those installed over the years. For example, the 180-day rule, where [officers] can’t be disciplined after 180 days after the time something happens. And there are rules that say officers get to view their investigative file and body camera footage before an investigator talks to them. Even if they are suspected of murder. Who else gets that? Can you imagine anyone else accused of murder, saying “Before we interrogate you, you can see everything in the file and the video and talk to your lawyer and craft a story”? No one but cops gets that.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Black Lives Matter