Listen to this episode on Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher | Google. Read the transcript below.

Subscribe

A couple of girls started running, then we started running, and then the crowd was running. We were running for our lives because these people were grabbing at us. My heart was beating so fast, and it was the first time I thought, “Why are people crazy? We’re just us.”

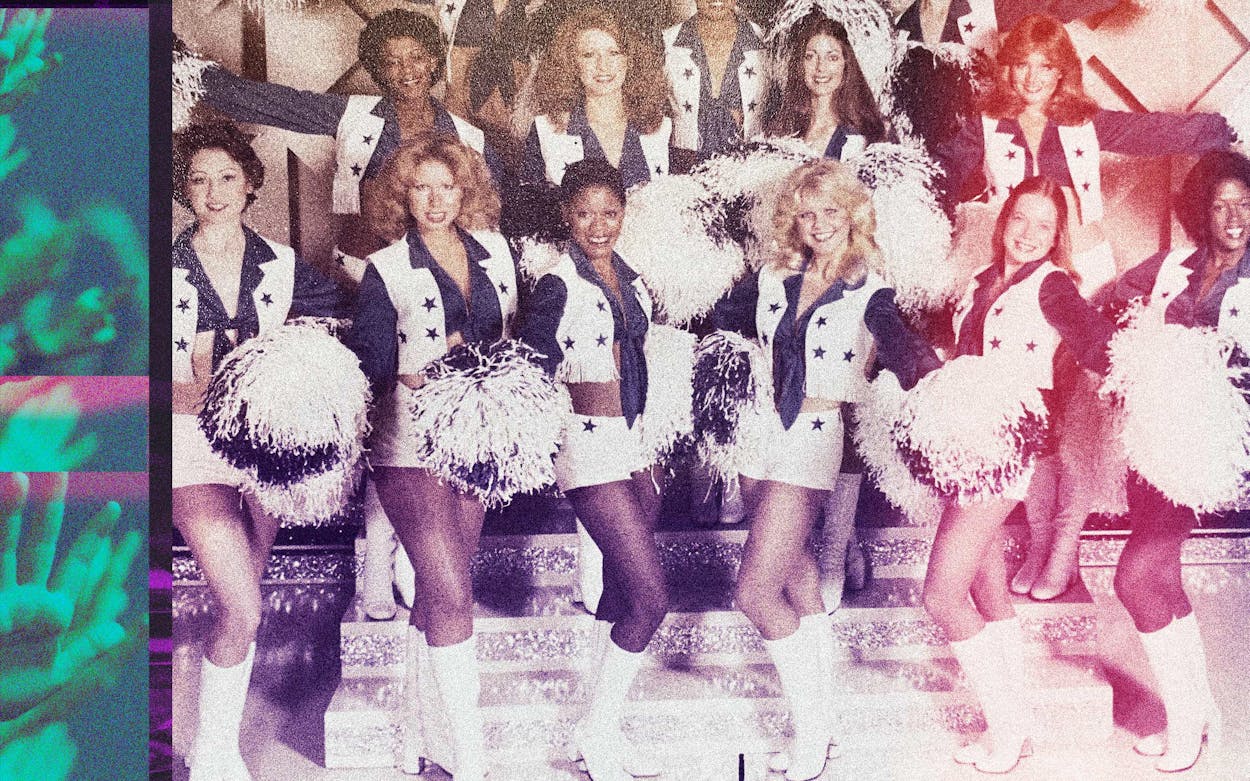

In this episode, the country is falling in love with the cheerleaders. Inundated with fan mail, they get the star treatment on television shoots and performances around the world. Former cheerleaders Shannon Baker Werthmann and Tami Barber recall the strange exhilaration of this sudden fame, and the stark contrast with their less glamorous daily lives, in which cheerleaders often struggled to pay the rent. And so much attention also comes with danger: hordes of screaming fans, threatening mail, and strangers watching them at home.

Dive deeper into the stories in this episode in our Pocket collection at getpocket.com/texas. You’ll find videos and news stories about the cheerleaders, including the cheerleaders’ appearance on The Love Boat and Robert Draper’s Texas Monthly story about longtime cheerleaders director Suzanne Mitchell, based on her final interview before her death.

Thanks to the UCLA Film & Television Archive for the audio from the documentary A Great Bunch of Girls, directed by Mary Ann Braubach and Tracy Tynan.

America’s Girls is written and reported by Sarah Hepola. Executive producer is Megan Creydt. Produced and edited by Patrick Michels. Edited by J. K. Nickell. Production, sound engineering, and music by Brian Standefer. Additional research and audio editing by podcast intern Harper Carlton.

Theme music is “Enough” by the Bralettes.

Transcript:

I was talking to this one cheerleader you heard in the last episode, who joined the squad just as they were getting famous.

Tami Barber: Okay. Tami Barber, 1977 through 1980. Wow.

It was mid-February, right when we had that awful winter storm here in Texas. She was in Louisiana, where the storm was just hitting—we were talking on Zoom and I was getting kind of worried.

Sarah Hepola: Wait, can you hear me? ’Cause you’re paused on my end. I don’t want you to be on the interview when they do the tornado warning.

Tami Barber: I’ll be sitting here and my things will just blow by, and you and I will just sit and talk. Some old lady on a bicycle with a dog in the basket goes by, let me know, okay?

Sarah Hepola: I’ll let you know.

And as the intense weather is closing in, she tells me this story. About the moment when the glamour and celebrity of being a Dallas Cowboys Cheerleader starts to change. The moment things get a little dark.

It happens at a college football game in Wichita, Kansas. The cheerleaders have come to dance in the halftime show. They’ve just finished and they’re sitting in the stands, just watching the rest of the game. But then . . . something shifts. The ones who see it first are the cheerleaders’ director, Suzanne Mitchell, and their choreographer, Texie Waterman.

Tami Barber: And Texie and Suzanne come up and say, “Girls, we’re getting up; gather your things. We’re going to the bus now.” And we look around, and it’s just like, people are swarming. They’re coming towards us in the stands. So we all just pick up our things, and we start walking.

I’m picturing this thing where everyone’s trying to act casual, but also, just trying to get out.

Tami Barber: And a couple of girls started running, then we started running, and then the crowd was running. And I mean, it was our Beatles moment, where we were running for our lives because these people were grabbing at us . . . Suzanne’s back there, like, trying to get these people to stand back, stand back. And we get in the bus and they close the door, and people are just pounding, pounding, pounding on the side of the bus.

And as the bus pulls away, through this horde, she kind of can’t believe what just happened.

Tami Barber: My heart was beating so fast, and it was the first time I thought, “Why are people crazy? We’re just us.”

This was November 1977, right as their poster was becoming a best-seller, and for Tami, the game was the first time this burst of fame seemed to come with a shadow side. How had it come to this? Where was this wild ride going? And was anyone really in control?

Tami Barber: And it was a transition of, “Oh my gosh, this is so cool. I really love it, and I love everything we’re doing,” to “What is really happening?” And . . . it touched something in my head that said, it’s time to start being really careful. Really, really careful.

I’m Sarah Hepola. From Texas Monthly, this is America’s Girls. Episode two: “All That Glitters.”

The woman in charge of the cheerleaders during this topsy-turvy time was Suzanne Mitchell. She was the one holding back those crowds in Wichita. Suzanne was in her early thirties when the Cowboys’ general manager Tex Schramm hired her as his secretary. She was back in Dallas after spending time at a New York publishing house. As the story goes, she was interviewing for a job when Tex Schramm asked where she wanted to be in a few years, and she said his chair looked really comfortable. He hired her on the spot.

She did payroll, contracts, the endless work of an assistant. But shortly after she came on in 1976, as the cheerleaders’ profile began to rise, Tex Schramm asked her to run the squad in her limited spare time.

Shannon Baker Werthmann: She was young and doing a heck of a lot.

This is former cheerleader Shannon Baker Werthmann.

Shannon Baker Werthmann: I felt how brave she was to enter into the bro world of football to stand up to Mr. Schramm, who was on this pedestal. . . . To be able to joke around with him.

Suzanne became one of the first female executives in the NFL. There was no road map for what she was doing, and she was bold—in her attitude, and often in the way she dressed.

Shannon Baker Werthmann: Now, she had the body of a model. So she could get by with a really low-cut leather vest, and throw a jacket over it and look really good. I thought she would be wearing a three-piece suit, her heels . . . She could play that part too, but that wasn’t her authentic self.

But she was also a deeply traditional person. She was the daughter of a military man, and introduced a boot-camp mentality that was a real jolt following Texie Waterman’s laid-back approach.

Doctor’s scales showed up in the studio. Practices ramped up, sometimes as many as five a week. There had always been rules, but now there were so many more. Blue jeans were banned, nails had to be manicured, and cheerleaders couldn’t be seen in uniform around alcohol.

Texie taught the cheerleaders how to perform, but Suzanne made them a machine.

Here’s Vonciel Baker, who was on the squad when she took over.

Sarah Hepola: Tell me about Suzanne.

Vonciel: Do we have three days?

Suzanne died in 2016, and she was a complicated figure, who commanded great respect—but also great fear.

Vonciel: I liked her, because—it’s so funny, but I’ve had my moments where I wasn’t sweating from dancing, I was sweating from talking to her.

More than anyone, Suzanne was the person responsible for their rise to fame—and she was very protective of them once they got there.

Tracy Tynan: She was very—a real den mother.

That’s Tracy Tynan, whose documentary, A Great Bunch of Girls, followed the cheerleaders during the 1978 tryouts. That year, more than a thousand women competed for thirty-six spots.

Tracy Tynan: She was very protective of them, and kind of like an old-fashioned chaperone, you know. She made sure that you adhered to all the rules and regulations, and if you didn’t, you were going to be tossed off the squad, and that was made very clear.

Mary Ann Braubach, her partner on that documentary, says Suzanne ran the cheerleaders like a football team.

Mary Ann Braubach: I looked at her as the person that is the scout, she oversees the draft, she’s the coach, and she’s the general manager.

And Suzanne was doing this in addition to her full-time job for Tex Schramm. The cheerleaders I spoke with said she hung back in the first year, not really asserting herself. But once she did, she was all in on crafting the culture and image of that squad. Here’s a clip from that documentary.

Suzanne Mitchell: “They have to be developed for our purposes in that they have to represent us a certain way.”

Suzanne was a shrewd marketer. She made sure the cheerleaders appealed to a wide range of fans.

Suzanne Mitchell: “There’s the little bitty girl in pigtails, there’s the tiny little Barbie doll look. There’s the ‘Miss Athletic.’ We want a little of everything.”

It was a bit like seventies Spice Girls. A sultry redhead. A perky brunette. An approachable tomboy. And while it might be overselling it to call the squad diverse, it’s worth noting that in 1978, there were six Black women on the squad out of thirty-six. That’s more Black women than the team had for much of the next four decades.

The dig on the cheerleaders is that they were appealing to male fantasy. But they were also appealing to women and little girls, who were eager to see themselves reflected in the macho world of men’s professional sports.

Suzanne Mitchell: “If I wanted to do any physical makeup or hair changes with you, would you have any objections?”

Candidate: “No, I don’t think so. Any suggestions to make me look better.”

Many of the women I spoke with talked about how Suzanne pushed them toward their better selves. Made them something they didn’t know they could be. Along with the rules, Suzanne instilled a sense of service on the squad that included goodwill missions to nursing homes and children’s hospitals. There was no doubt, Suzanne could be an inspirational figure. But at times, she could also be pretty harsh.

Tami remembers the day Suzanne told her she was getting a new look.

Tami Barber: Suzanne called me into Texie’s office, and Suzanne said, “Texie and I have decided that you’re gonna wear your hair up in pigtails from now on, for the games and for anything we do.” And, I was like, “Okay. Uh, why?” And then, what she said to me, I will never, ever forget. Because I was, what? Nineteen, twenty years old? And she said, “You’re not pretty enough, and you need a gimmick.”

Tami was in shock. She’d never been around this kind of cutthroat atmosphere—she’d grown up in Nebraska, an only child with two parents who always supported her.

But Tami didn’t push back. She wore the pigtails, played the part she’d been given at every appearance. What else could she do? She had to try out again each year to stay on the squad. And every year, she was up against more than a thousand girls who wanted her spot.

Suzanne liked to remind everyone: you can be replaced in a second. She had certain lines they all knew by heart. Another one they heard all the time: It’s the uniform that makes you. You don’t make the uniform.

Tami Barber: So, I hated the pigtails at first. I took her words so deeply to heart that it shattered me for a while. And then, it was almost as if the universe decided to turn it around and make me feel better by making the pigtails as big as life.

Suzanne’s makeover made Tami one of the most recognizable cheerleaders of the seventies. The look catapulted her into the spotlight, and she was featured on posters and merchandise, along with her best friend on the squad, Shannon Baker Werthmann.

Shannon Baker Werthmann: I was a cheerleader from 1976 to 1980.

This is Shannon.

Shannon Baker Werthmann: I just remember my dad saying, why don’t you do this? Maybe we can get some free tickets if you go and try out for this thing.

She’d hoped to become a ballet dancer, but her petite, buxom body wasn’t a fit for that world. But she was a perfect fit for the cheerleaders. Shannon had that Farrah Fawcett hair, and killer high kicks. When the Cowboys released a cheerleader doll, they called it “Shannon.”

Like the other cheerleaders, Shannon had a busy life off the field—she was studying broadcast journalism at SMU, and she had rehearsals and appearances. And on top of that, she had to write back to her fans. That was another one of Suzanne’s rules: you had to write back.

And Shannon got a lot of mail. From girls who wanted to be dancers and cheerleaders when they grew up. And from boys who had her poster on their bedroom wall.

Shannon Baker Werthmann: And I probably wasn’t that much older than they were. They’re like twelve and I’m seventeen. And then I had a gentleman that was from Mexico that would send me a weekly sombrero.

Sarah Hepola: Were the sombreros different?

Shannon Baker Werthmann: Oh, very. And they were the big sombreros, like, big.

Shannon still has a lot of these letters. She read me one from a boy named Russ, who lived in Connecticut. They corresponded for years.

Shannon Baker Werthmann: “Dear Shannon, Hi. Thanks so much for writing back. I never dreamed you would, but here’s the letter. I’m so excited. Thursday, I went down to the pharmacy where my mother works and told her I received an A on my math final exam.” So see, it’s so nice they want to share with us the details of their life.

And I won’t play you the whole thing here. It’s really long. But pretty articulate for a fourteen-year-old boy. And as I’m listening, I’m thinking about a time when I wrote letters like this to my celebrity crushes, and I have such affection for that kind of fandom, for a kid hoping to be more than one more anonymous person in the stadium.

Shannon Baker Werthmann: “Shannon, I’m so happy you made the squad again this year. I can’t wait to see my favorite gorgeous Dallas Cowboy cheerleader, you. Did you know it was you? Thanks for the schedule and decals. I love you. Russ Dunham.”

Sarah Hepola: That was amazing.

Shannon Baker Werthmann: My heart. And I appreciate—I mean, I’m sure I appreciated it then, but I appreciate it more now. Isn’t that the sweetest?

And—I couldn’t help myself, there was someone I just had to ask about this letter.

Russ Dunham: Russell Henry Dunham the fourth. And I grew up in West Redding, Connecticut, fifty miles from New York City.

Russ was five or six when he became a Cowboys fan—and that decision has stuck.

Russ Dunham: That was who I was and still am to this day. There’s not another team that would come close to the love that I have for them.

And I asked him what he remembers wanting to say to Shannon at this point in his life, why he chose her. What kind of a connection was he looking for?

Russ Dunham: Not that there wasn’t a crush, but I never thought of, like, that I could be a boyfriend or anything. I don’t think I ever thought that. It was just kind of like, I want to be part of the Dallas Cowboys and friends with the Cowboy cheerleaders, and I wanted to be there every day. And my dream was to work for the Dallas Cowboys. So . . .

Sarah Hepola: So, okay. So I want to read to you this letter now. Are you ready? Are you nervous?

Russ Dunham: I don’t know. Oh, I’ve been nervous since I got your email the other night.

Sarah Hepola: Did you know that you sent two little pictures with it? Two little Instamatic pictures? It’s you in your Cowboys bedroom.

Russ Dunham: Wow.

Then I read Russ his own letter from forty-plus years ago, and—I’ll skip to the end.

Sarah Hepola: “This summer I’ll be back in Miami visiting my brother Louis. I’ll probably go to the beach a lot in search of girls.”

Russ Dunham: Yes, sir.

Sarah Hepola: And then you say, “Don’t be jealous.”

Russ Dunham: Oh my goodness.

Sarah Hepola: “I can’t wait to see my favorite gorgeous Dallas Cowboys cheerleader, you. Did you know it was you? I’ll see you on TV. By the way, since you can’t send me an autographed photo, how about one of yourself just sitting at home in your bikini?”

Russ Dunham: Oh my God! Oh my goodness gracious.

Sarah Hepola: I know, I know, I know. It was bold. I mean, listen, you are a teen boy with, like, a dream and a mission. It is amazing to behold.

Russ Dunham: Whoo. Boy. Got to step back from that, huh?

And I was curious what it felt like to be Shannon—getting these notes from people you don’t know who are looking for something from you.

Shannon Baker Werthmann: You know, I’ve had fans say, ‘You’re like part of our family.’ And they became like, part of our, you know—my family. And it’s just, I don’t know. It’s just really, really sweet.

Tami got a lot of fan mail, too. She was, after all, “the girl with the pigtails.” But Tami’s fan base was a different demographic.

Tami Barber: Yes—the majority of my fan mail was from little girls who would send me a picture . . . They were in their homemade uniforms. And they would tell me how they watched the games, and they looked for me, and they always had pigtails in their hair. And then the one thing that I got that I think about, if it were to happen today, I could probably end up in prison—moms and grandmas would send me pictures of their grandsons, or their sons. And do you remember Underoos?

Sarah Hepola: Oh, I do. Oh, I do.

In case you didn’t know, Underoos were very popular in the late seventies—basically kids’ underwear with superheroes and sports team logos.

Tami Barber: They would be in their Cowboy Underoos. They’d be standing in their Cowboy Underoos, with a football in their hand. And then the letter would be from Grandma or Mom saying, “You’re our favorite cheerleader.” And it would be funny because there’d be Shannon sitting next to me, and she’d have, like, this picture of this really cute guy that wants to know if she has a boyfriend and how much he loves her, and he thinks she’s so beautiful. And then I got Underoos. I’d be like, “Well look at my new boyfriend. He’s seven.”

Being a cheerleader was such a random assortment of surprises and opportunities. It was like your side hustle was being a celebrity—they’d do these amazing things, then come home and live their regular lives. They took a two-week tour of Japan, sponsored by Mitsubishi. In 1980, they even put out a record. It’s a little light in the lyrics department, but it has a lot of spirit.

Cheerleaders singing: Outrageous, it’s contagious when we start to scream . . . We’re the best; better than all the rest; we’re football’s number-one dream! We love the Cowboys!

And then there were all those appearances on telethons and the variety shows that flooded the airwaves. The one that Shannon remembered most vividly was The Osmond Brothers Special.

Osmond Brother: “We’ve got Bob Hope, Crystal Gayle, Andy Gibb, Jimmy Walker, and . . . the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders!”

Osmond Brother 2: “Are they really that neat? I mean, in person?”

Shannon Baker Werthmann: And, first of all, it was gorgeous. I mean, we’re in the mountains. We are treated like princesses, like royalty. You know, with the limos, and the—we get there and we have a large spread of food waiting for us. And we got to go to Donny and Marie’s home. Which was so cool to me—I thought that was really cool going into her bedroom. And it was like, light pink bedspread, and her collection of dolls. And I mean, she was just—it was like, she’s a girl. She’s just a girl like us.

It’s easy to forget how young the cheerleaders were. You had to be eighteen to try out, but Shannon was seventeen and she didn’t want to wait. So she lied on her application. A lot of the other cheerleaders were nineteen, twenty, and they still saw themselves as girls too. And they were pulled into the orbit of all this fame.

Shannon Baker Werthmann: You’d look out over the beautiful mountains and see the twinkling lights down in the city below. And I mean, it was just, it was so cool. And you did have to pinch yourself. I mean, that was—that was dreamlike to me.

The run continued. Awards shows. The Love Boat. A hit TV movie. But for a lot of cheerleaders, these moments on the pedestal could be hard to square with the messy financial realities. Sometimes, the most important thing about these appearances was just a chance to make some money. Because they got paid extra for special events, usually between three hundred and five hundred dollars.

Tami Barber: We were poor. We were all very poor. There was so much time spent with the Cowboys that it was hard to keep a full-time job.

This is Tami Barber again.

Tami Barber: And truthfully, appearances to me meant, “Oh, thank goodness, extra money. I’m going to get to pay, you know, a bill.” That’s all it really was in my head, is, “Oh, I need an appearance. I really need an appearance, because that is good money.”

And among the thirty-six cheerleaders, there was this inner circle of women Suzanne would handpick for these appearances, and the competition could be intense. The hobby that the Cowboys created had become more like a full-time job.

Tami Barber: All the calendars, all the playing cards. Everything—the movies. Everything. They made millions. And the funny part is that other people thought I was making money. A high school guy that I went to high school with became a stockbroker, and he was always sending me stuff and wanting to know if I would invest. I never told him that I made fourteen dollars and twelve cents after taxes on a game.

Shannon was living rent-free with her family during these years, but other women weren’t so lucky.

Shannon Baker Werthmann: There were so many broke cheerleaders at that time that weren’t able to pay their rent. It was all fine and good at the beginning, but then when you can’t pay your rent for multiple months and you’re working so hard and you’re falling asleep at your desk at work because you’ve been working all night at rehearsal, and you’re seeing all of this wonderful publicity coming around you, and you think, “For sure I have a place in this mix, monetarily,” you know, that we’re making all this money for the team, but where is it?

For the Cowboys, it was actually a point of pride that these women worked so hard for the team, for almost nothing. Like, look how much they love this team.

Shannon Baker Werthmann: And that was pounded into our heads. “If you’re doing it for the money, you need to get out, ’cause you’re not going to last very long.”

Suzanne gave everything she had to the Cowboys—and she expected that same level of sacrifice from the cheerleaders too.

Tami Barber: I know personally, I would fall asleep at work. I was exhausted. If you’re working nine to five and then you have to be at practice at six, clear across Dallas, you’re eating junk in the car. . . . You got home at two in the morning. You got back up at six, you went to work, you repeated it. You know, five days a week, six days a week. And then there was the day of the game. I mean, it was—it was constant. Even though it’s like, “Wow, I can’t believe I’m here. I can’t believe I’m on the sidelines of Texas Stadium.” It was a hobby. You weren’t going to make money doing it. This was a hobby and an honor. And after a while, you’re like, “Honor this. I’m broke.”

On top of the constant hustle, there was a vulnerability that came along with the spotlight.

Tami lived alone in an apartment in Irving while she kept this exhausting schedule. And one night, after she’s finally home, she shuts off the lights, climbs into bed . . .

Tami Barber: And my phone rang, and a man’s voice said, “Goodnight, Tami.” I don’t remember if I immediately hung up, or I might’ve said, “Who is this?”

A few days later, same thing. Tami gets home, climbs into bed, and the phone rings. She picks it up and she hears: “Goodnight, Tami.” After that, she starts going to sleep with the lights on.

Tami Barber: And even though my lights were on, as soon as I climbed in bed, my phone rang and the same voice said, “Goodnight, Tami.”

Within days, she moves to a new apartment.

Tami Barber: I was scared to leave my apartment, and I was scared to be in my apartment, and I have no idea who it was. No one ever came to my door. How he knew when I was getting in bed, I don’t know, even with lights on.

It terrified her, but she never told anyone.

Tami Barber: Girls were sent—I mean, prisoners, oh my gosh, the fan mail from prisoners was unbelievable. And then the crazy people who would say, “You’re not writing back to me. What is wrong with you? You need to write back to me.” Then we found out that Suzanne was not giving us the hate mail. All our mail started coming already opened; they were screening our fan mail.

Suzanne saw herself as a protector. Behind the scenes, she was known to take cheerleaders under her wing. She counseled them over abusive boyfriends; she paid for their divorces. Those strict rules weren’t just designed to maintain the image, but also to maintain their safety. Here she is again, in that 1979 documentary.

Suzanne Mitchell: “Don’t ever give anybody your home phone number, ever. Or your home address. You will find probably by mid-season, if not before, you’ll have to have an unlisted phone number. And don’t give out any information about any other cheerleaders. It’s for your own protection.”

After multiple mob scenes like the one in Wichita, the cheerleaders got security guards at every public event. But outside those events, there were elements Suzanne couldn’t control.

Tami Barber: Because many girls had stalkers; it wasn’t just me that had to move because somebody found out where I lived. There were several people, several girls, who had to do that.

I talked to another cheerleader. Today, she goes by Billie Mitchell.

Billie Mitchell: . . . and as a cheerleader, I was Billie Gosdin and I am an alumni of 1979 and ’80.

And in her one season with the cheerleaders, she had multiple threats from strangers.

Billie Mitchell: Well, it was actually when I was still cheering. I had butcher knives sent to me. A big set of butcher knives in a manila envelope with a letter, and it was a sick, crazy typewritten letter from Pittsburgh. It was wrapped up in Pittsburgh Steeler newspaper, which that was one of our big rivals back then. And I thought my husband bought me butcher knives or something at first, and then I started reading it. The letter was like, “Billie, my goddess of love.” And it was just sick.

And then, another night, she comes home from a movie with her husband and her daughter. And her husband lays down on the couch, and Billie goes alone to her bedroom and lays down on their waterbed. And she’s lying there in the dark. And she can feel somebody watching her.

Billie Mitchell: And the police said that I threw him off because I jumped up thinking something was wrong.

For an instant, she thinks maybe her husband, Steve, has come in from the other room.

Billie Mitchell: Steve had a robe on, and he had on, like, suede. I felt suede. So subconsciously, I knew it wasn’t Steve but I kept talking to him like it was. I kept going, “What do you want?”

And this stranger, he just turns, and starts walking away. And Billie follows right behind him.

Billie Mitchell: And it wasn’t till he got to the kitchen where the light—the oven light was on, and I saw his face and then I go—I just started trying to scream and nothing came out. And he had already had his way to go out the door. And that was just my first year.

And so . . . she ended up moving too.

Billie Mitchell: And I didn’t sleep, at night, probably for twenty years. I mean, I would go to sleep as soon as dawn hit. I mean, it just messed up my head—and I went to counseling for it and stuff, but it was just a—it was a hard deal for me.

And that wasn’t even the last of it. A little later, she’s just come home from the hospital with her second daughter.

Billie Mitchell: And the neighbors came over and said, “There’s somebody standing outside your window.” So, um, we moved right after that.

Billie left cheerleading after a year. It just wasn’t worth the stress. And maybe it’s worth asking why anyone would put up with this—the rules, the low pay, the creepy stalkers.

There’s no one reason why so many women wanted to be a part of this. For some, like Shannon, it was a chance to have a dance career, one much closer to home than New York or L.A. And for everyone I spoke to, there was the extraordinary experience of game day.

Tami Barber: It was the biggest thing I’d ever seen in my life. There’s something about an NFL field that, for me, I feel really tiny. And I’m in this dome of amazement—whoa, takes my breath away. Literally. When I am on the field in a performance, my heart is just, like, huge.

And during the late seventies, when young women didn’t have so many ways to make it in a world run by men, being a cheerleader came with a rare status. Tami’s father was a devoted Cowboys fan, and it amazed him that she became a part of the game. This was a chance to be somebody. Even when she cheers on the field for alumni events, that feeling returns.

Tami Barber: I remember one of the years that I went back, I literally could not breathe. I was so overwhelmed with emotion—the tears were just shooting out of my eyes and I couldn’t take a breath because I was back on the field, and my brain went back to that time.

Sarah Hepola: What do you think you were feeling?

Tami Barber: Um . . . I was back to a time where I thought I was a grown-up, but I wasn’t. I was a little girl who had made her dad’s dream come true with the Dallas Cowboys, and I had made the best friends of my life, and they still are today. I mean, it was home. I was home.

The bonds of friendship. The foxhole mentality of being united by—or against—Suzanne, it shaped them at such an impressionable time in their lives.

The 2018 documentary Daughters of the Sexual Revolution follows the cheerleaders during Suzanne’s era, and it’s a dynamic portrait of their influence. Its director, Dana Shapiro, told me he was moved by how deep this experience had been.

Dana Adam Shapiro: At the end of the day, it really was kind of this family story. When you speak to these women, after interviewing them, you know, they would speak about their own mothers, and then they would speak about Suzanne—in similar tones, you know. That she guided them, she showed them what was important. And they say, you know, “It might sound silly because it seems so frivolous—cheerleading—but this is where I found purpose and meaning.” I mean, that’s really what we’re all looking for. I think you go through life looking for something like that.

Purpose, meaning. These are no small things. We’re all looking for ways to feel connected to something greater than ourselves, and this sideline experiment had become a transformative institution.

But I also can’t help noticing how well this arrangement served the Cowboys’ bottom line.

They were asked to be starving artists, in the context of this multimillion-dollar institution. The way I see it, that’s just one of the tensions that was baked into the experiment. They were told they were special and also instantly replaceable. They had to be good-girl brand ambassadors and also sexy pinups. And as the world came at the cheerleaders, the Cowboys had to keep those young women safe and, at the same time, perpetuate the male fantasy that made them famous. The Cowboys had to control this wildfire at the same time they fanned the flames. There were all these tensions—and by the end of 1978, they were about to explode.

Next time on America’s Girls:

Debbie Kepley: We were the first Dallas Cowboy cheerleaders to ever show our breasts to the world. And that one thing, I think, caused so many problems.

- More About:

- Sports

- Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders