Listen to this episode on Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher | Google. Read the transcript below.

Subscribe

We were the first Dallas Cowboy cheerleaders to ever show our breasts to the world. And that one thing, I think, caused so many problems.

Debbie Kepley

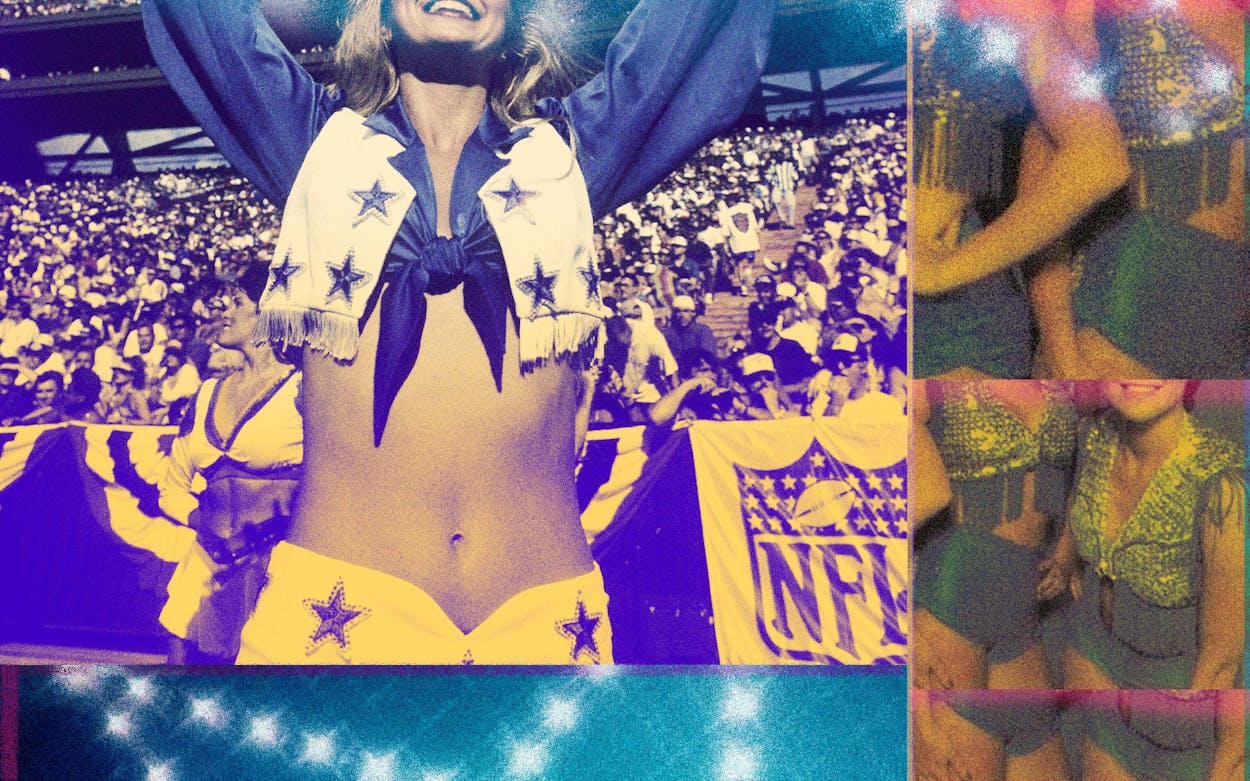

In this episode, we follow the scandal that erupted when five former cheerleaders posed for Playboy in 1978. The nudity made this such a sensational chapter in the cheerleaders’ history, but the story—literally, the Playboy article accompanying the photos—also raised questions about fair pay and who gets to profit from the cheerleaders’ sexualized image. These former cheerleaders were part of a rogue outfit called the Texas Cowgirls, a talent agency built to meet the demand for young, beautiful entertainers, and share their profits in an egalitarian way. But the Playboy episode became a mess for them, personally and legally. Debbie Does Dallas came out the same year—it marks the point when the sexual fantasy the Cowboys introduced to American homes was getting very tricky to control.

You can dive deeper into the stories in this episode in our Pocket collection. You’ll find videos and news stories about the cheerleaders, including 1979 news coverage of the NFL cheerleaders’ Playboy scandal and Christopher Kelly’s 2008 Texas Monthly story looking back at the legacy of Debbie Does Dallas.

Thanks to the Dallas History & Archives Division of the Dallas Public Library for research help on this episode. You can read more about the stories in this episode in Frank Andre Guridy’s book, The Sports Revolution: How Texas Changed the Culture of American Athletics. Credit to the UNT Digital Library and KXAS-TV for news footage of the Debbie Does Dallas trial.

America’s Girls is written and reported by Sarah Hepola. Executive producer is Megan Creydt. Produced and edited by Patrick Michels. Edited by J. K. Nickell. Production, sound engineering, and music by Brian Standefer. Additional research and audio editing by podcast intern Harper Carlton.

Theme music is “Enough” by the Bralettes.

Transcript

In January 1979, a made-for-TV movie came out that was all about the Cowboys cheerleaders.

It starts with a magazine editor in his high-rise office in New York, watching football.

Editor: “I’ve been watching that cassette of the Super Bowl for a week. You know where the TV cameras spend most of their time? On those girls. The Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders.”

And like plenty of real-life magazine editors around that time, this gets his wheels turning.

He’s determined to get the dirt on the cheerleaders.

Editor: “All that goodie-goodie, look-but-don’t-touch nonsense, I want to cut through all that phony PR and show those girls for what they really are!”

He dispatches his ex, a feminist journalist played by Jane Seymour, to try out for the team and get the real scoop. The premise borrows from a famous exposé written by Gloria Steinem. She posed as a Playboy bunny at Hugh Hefner’s New York club and wrote about the ugly truth of life as a sex object. But this movie is a little less hard-hitting.

Cheerleaders director Suzanne Mitchell got to approve the script, and the journalist’s search for dirt ends with a twist.

Jane Seymour: “I’ve been thinking that maybe we’re on the wrong track. There just is no story. The Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders are everything that their PR says they are: they’re just a lot of nice, down-home girls having fun.”

Reviews of the movie ranged from “corny” to “junk” to “one of the worst made-for-television movies since Maneaters Are Loose!”

But it became a smash. It was the highest-rated made-for-TV movie of the year.

You’ve heard a lot about how popular the cheerleaders were—but there was something else behind those ratings.

Because in the months before the movie aired, a scandal rocked the NFL. A scandal about sex, and who gets to sell it. It was about the meaning of exploitation. It was about money. And it began with five former Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders opening their halter tops.

Debbie Kepley: We were the first Dallas Cowboy cheerleaders to ever show our breasts to the world. And that one thing, I think, caused so many problems.

I’m Sarah Hepola. From Texas Monthly, this is America’s Girls. Episode 3, “Naked Ambition.”

Debbie Kepley joined the squad in 1976, right as the cheerleaders were taking off. She tried out in secret. She didn’t want anyone to know if she didn’t make it. And she mostly thought being a cheerleader was fun. She liked the rehearsals, liked learning to dance with the other women.

Debbie Kepley: It’s a sisterhood. It was like, oh, this many women can get together and get along? Then you build up a friendship with all these different girls.

She spent two seasons with the cheerleaders. When she started, she’d been working as a clerk at a federal court. But she quit because the cheerleaders’ schedule was so unpredictable. She took a job bagging groceries at Kroger instead.

Before her cheerleading days, she’d loved the Dallas nightlife.

Debbie Kepley: Lots of nightclubs. The Point, Papagayo’s, Le Jardin. Let me see, Playboy Club. There was so many nightclubs. And you get free drinks if you dance. I knew all the guys who opened the nightclubs.

But once she joined the squad, she couldn’t go out dancing at night on her own. That was cheerleader director Suzanne Mitchell’s rule. Cheerleaders weren’t allowed inside the Playboy Club at all, even though it was in the same building as the Cowboys headquarters.

Debbie Kepley: I guess you’re always in fear that somebody is going to find out you’re a Cowboy cheerleader and you did something wrong. They always put this fear over you: either do this, like we say, or you can be replaced because we have alternates sitting in the wing waiting to take your job.

Sometimes being a cheerleader wasn’t so great, especially when she was making fourteen dollars and twelve cents a game.

Debbie Kepley: Just shake your pom-poms, that’s it. Glow and shake your pom-poms. But don’t talk to anybody. Wink at the camera. Smile at the camera. But don’t talk to anybody. I don’t like people telling me what to do. I think it comes from being raised by a single mom, and her strengths of taking on the world and raising me by herself.

Debbie was willing to conform to the squad in a lot of ways. She was a brunette in a blonde’s world, and she did what she could to get her body to look more like the others.

Debbie Kepley: I didn’t have cleavage. So a lot of people don’t know this, that there was a certain way we had to tie our shirts. Because they wanted you to have the most cleavage, so the knot had to be tied a certain way so you had that look.

But there was this one moment when she drew the line. When Debbie came back for a second season, Suzanne Mitchell told her to start wearing her hair in pigtails.

Debbie Kepley: And she grabbed my hair and she pulled it up in a ponytail, and she goes like, “I want you wearing pigtails again all year.” And I’m like, “Oh, I don’t want to,” and she said, “Yes, you will.” So, I went and cut all my hair off. And she didn’t fire me, but she could have because I didn’t abide by the rules.

Of course, this was the same makeover Suzanne wound up giving Tami Barber. The look that made Tami a star.

Looking back now, Debbie realizes her decision probably cost her a lot of money, hundreds of dollars for every one of the appearances Suzanne might’ve chosen her for, if she’d just worn the pigtails. Playing along had its rewards.

Debbie Kepley: It’s the goody-two-shoe girls, is what I call them, the ones who never said no to the system or questioned the system. Those are the ones that got all the work.

But while Debbie chafed against the system, it was still an exciting ride. Especially at the end of her second season, when the squad went to New Orleans.

It was January 1978. This time the TV cameras really spotlighted the cheerleaders as a central piece of the action.

Frank Andre Guridy: But that’s when you see the impact of the Dallas Cowboy cheerleaders.

This is the historian Frank Andre Guridy. He says, if you were watching this game at home, you couldn’t miss how valuable the cheerleaders had become.

Frank Andre Guridy: They are literally, Tom Brookshier and Pat Summerall who were calling that telecast say, “Oh, this is a battle of the cheerleaders as much as it is of the players on the sideline.”

Tom Brookshier: “My heavens.”

Pat Summerall: “There is great rivalry between the Denver cheerleaders and the Dallas cheerleaders.”

Frank writes about this game in his book, The Sports Revolution. The cameras keep cutting away to linger on the Cowboys cheerleaders as they swish their pom-poms. Or to the Denver Broncos Cheerleaders—the Pony Express—in their silver fringed bikini tops and tiny sarongs.

Monday Night Football did this sort of thing all the time, but Frank says this Super Bowl game took it to a whole new level. The cheerleaders were practically foisted into a honey shot throwdown.

Tom Brookshier: “A little competition going on down there, do you feel that?”

Pat Summerall: “Also, there is a game. Third and eighteen.”

Frank Andre Guridy: So that really gives you a sense of the ways in which these women are becoming famous, but almost completely through the lens of the male gaze.

A hundred million people watched that Super Bowl game, and the cheerleaders, now more than ever, were a major part of this winning package. But backstage, Debbie says the cheerleaders were treated more like an afterthought.

Debbie Kepley: The performance was great, and then the game was great. We won. And the after part was the sad part. We were hurried off, back to the bus. We were taken behind the gate. Not even through the airport like normal people. We were put behind security onto a plane, where we sat and sat with no water, no food, no nothing for hours and hours.

It was a commercial plane, and the cheerleaders sat there all night—stuck in a post–Super Bowl runway traffic jam.

Meanwhile, the Cowboys got a big victory bash near their hotel, with performances by Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, and Jerry Jeff Walker.

The cheerleaders had not been paid a dime for their appearance—not even their usual fifteen bucks. The Cowboys didn’t even pay for the cheerleaders’ travel to the Super Bowl. They had a sponsor cover the expenses. Sports Illustrated wrote about this a few months later—when it came to being cheapskates with their cheerleaders, they said, “Dallas may hold the record.”

Debbie Kepley: They have enough money. It’s ridiculous. But it just made you feel worthless. All the hours you put in to be a part of the Cowboy cheerleaders, all the hard work, the sweat, the tears, the blisters on your feet, and doing everything they tell you to do. And you finally go to the Super Bowl, they win, and then you’re stuck on a plane? For hours? And it’s like nobody cared?

While the Cowboys were celebrating in New Orleans, and fans in Dallas were throwing parties back home, the cheerleaders had to celebrate on the tarmac.

Debbie Kepley: I just remember a lot of the girls that consumed alcohol were drinking quite a bit, and talking to the regular public that were stuck on the plane with us. And after a while, there’s a lot that said, “I’m not going back for this. This is ridiculous that they leave us sitting on a plane like this.” And it’s just, I was over it.

It wasn’t just the women who’d been stuck on that plane. Conflict had been brewing around the cheerleaders for a while—women who hadn’t made the squad, women who had made the squad but were tired of the low pay, the rules, the feeling of being controlled. Women who’d gotten a taste of the spotlight and wanted more.

And in the summer of 1978, a bunch of them joined forces. They called themselves the Texas Cowgirls.

A former cheerleader named Tina Jimenez came up with the idea. She was an enterprising single mom who had cheered for the Cowboys in 1976 and been cut in the next auditions. She figured, why should the Cowboys be the only game in town?

I tried to reach Tina, but she never responded to my messages. Here’s Debbie Kepley:

Debbie Kepley: Tina formed the Texas Cowgirls because she kept seeing a lot of girls that auditioned and didn’t make it, or had to leave because of issues, you know, they didn’t follow the rules. So she figured they’re dancers. They’re beautiful young girls. They know how to do promotions.

Janice Garner: Yeah, I had way more fun being a Texas Cowgirl than I did a Dallas Cowboy cheerleader.

Janice Garner was another member of the Cowgirls.

Janice Garner: Fewer rules, more money, just easygoing and fun.

Janice was 21 when she became a Cowboys cheerleader. She loved dancing at the games, but she says she never quite fit in.

Janice Garner: It was wonderful and horrible at the same time. The fun part was being on the field and feeling all that energy that was coming from the stands.

But she struggled to pick up the dance moves. And she got in trouble with Suzanne for things she’d never even imagined were problems.

Janice Garner: I got called in for a couple things, and one was for showing too much cleavage. She wanted me to look more like the girl next door, and—

Sarah Hepola: That’s really interesting.

Janice Garner: I know. Go figure. Because (laughs) I guess I’d tie the bow too tight. I can’t figure out how I could have too much cleavage.

This was the needle the cheerleaders were always trying to thread: You had to have cleavage, but not too much cleavage. You had to be sexy, but not too sexy. Janice didn’t try out again—she joined the Texas Cowgirls instead. There were 25 of them in all. Here’s Debbie Kepley:

Debbie Kepley: We had these silver boots, and we had an electric blue spandex type one piece that zipped up the front, and a cowboy hat.

And the money they earned wouldn’t get sucked up into a giant corporation. It would be shared among the women. The best opportunities wouldn’t go to a few favorites—everyone got an equal chance to earn money.

Their pitch was simple.

Debbie Kepley: We’re former Dallas Cowboy cheerleaders that would make personal appearances, usually where Dallas Cowboy cheerleaders would not make an appearance.

So, like private parties where alcohol was served. Or anywhere Suzanne decided she didn’t want her squad.

Janice Garner: They would hire us to appear and sign autographs, like at car dealerships, auto shows, openings, parades.

Debbie Kepley: And we would do Ducks Unlimited auctions, which means we would walk across the stage with whatever it was that was being auctioned, and then it was all men, yelling and screaming at you.

Along the way, they got to boogie on Merv Griffin, they performed at the Winter Olympics in Lake Placid, and they appeared in the movie North Dallas Forty, which was a fictionalized version of life inside the hard-partying 1970s Cowboys.

North Dallas Forty quarterback Seth Maxwell: “You girls ever try a quarterback sandwich?”

Woman: “Sounds good to me.”

The movie poster has two Texas Cowgirls in their shiny blue spandex and silver boots. Debbie’s one of them.

Frank Andre Guridy: So, they’re this rogue outfit that’s like, “You know what? We’re sick and tired of the Cowboys’ rules. We’re sick and tired of the exploitation. We’re just going to go out and make money ourselves.”

This is Frank Guridy.

Frank Andre Guridy: And that’s what they do, at least for a little while. And one of their things that makes them famous is the Playboy shoot that was eventually published in December 1978.

Jeff Cohen: We always had interest in putting our own editorial spin on what was going on in society.

Jeff Cohen was the photo editor of Playboy back then. And Playboy was a huge deal in 1978. This December issue is as fat as a phone book.

Jeff Cohen: The NFL was having an explosion in popularity, and with it were the cheerleaders that were strutting their stuff along the sidelines.

Jeff would travel the country, scouting for talent. He had come up with other big features, like “Girls of the Big Ten” and “Women of Mensa.” Cheerleaders and Playboy: it’s not rocket science.

The package included members of the Chicago Honey Bears, the San Diego Chargettes, the Seattle Sea Gals, and the Los Angeles Rams cheerleaders, the Embraceable Ewes. (That’s e-w-e, in case you missed the pun.)

Some of the squads gave the women permission to pose only if they kept their clothes on. Other teams didn’t put any limits on their cheerleaders, and about half the women are seminude.

Jeff was surprised by how gamely some NFL teams opened their doors when Playboy came knocking.

Jeff Cohen: Maybe in a way—and I never have thought of this until now—but maybe in a way they were envious of Dallas. Dallas was the one that always would get sort of any publicity or TV or magazine coverage about the NFL and cheerleaders.

Jeff Cohen: So clearly they were the ultimate cheerleading group. If indeed we, Playboy, were going to do a feature on pro football cheerleaders there was no question Dallas had to be part of it.

Well, the Cowboys’ front office was not so enthusiastic. But when the team said no, Jeff knew just who to call.

Janice Garner: Oh, Tina told us. She was all over it, and thought it would be a great thing. Most of us were struggling back then. You know, who doesn’t want to make a bunch of money?

And then—at least for some of them—there were the bragging rights. To say you’ve been in Playboy. Here’s Debbie again:

Debbie Kepley: I grew up in a generation where the Playboy magazine was around, and men would have it, and then teenage boys had it, and then it’s like, “What’s so special? Why do you want to look at this girl in this magazine? If I’m your girlfriend, why is that so much better than me?” And I thought, “Well, if I ever get the chance, I’ll do it.” And for me, it’s like, to all the guys that I ever dated. I just like, “See? See now?”

For Janice, it was just the opposite. She didn’t want anyone to see it.

Janice Garner: It was pretty lame, but I honestly thought, “Okay, my parents go to church. They’re good, upstanding citizens. They don’t read Playboy magazine. They’ll never see it, right?” We didn’t have the internet back then, so I thought, “It’s just going to be in a magazine, and then it’ll be over with, and end of story, right?. No big deal.” Well, it turned out to be a big deal, unfortunately.

On the day of her shoot, she shows up at a stranger’s house, and meets the photographer, a guy named Arny Freytag.

Janice Garner: So, I asked Arny, “What am I going to wear?” and he holds up this little pair of panties and a scarf, and I was mortified. Then it really set in, you know.

In the photo, Janice perches herself sideways on a couch with that thin scarf around her neck. Her long legs are draped across the cushions.

Debbie also got a solo shot in the magazine, emerging topless from a swimming pool. It took hours to get everything just right.

Debbie Kepley: I mean, it’s like a workout beyond belief to make a picture look the way it does, because they didn’t airbrush back then the way they do now. But you had hair and makeup people on you, costume people, people taking care of you like you’re a queen to get this one photograph.

But the centerpiece of the issue was a group shot. It’s a riff on the famous 1977 poster that the Cowboys released. This one has the five ex-cheerleaders standing in a V formation. Smoke billows around their white go-go boots, and they’re wearing very similar uniforms to the original. But this time the halters are untied to reveal their breasts, as each locks eyes with the camera. Front and center is a blonde ex-cheerleader named Linda Kellum, flashing her top wide open. It’s an image that’s part seduction, part satire, and part defiance.

And then there’s Janice, just to the right of center, standing with her pom-poms resting on her hips and her face just . . . blank.

I’d seen this photo so many times, trying to read their expressions. But I look at it now, and I wonder if Janice’s face is betraying how she really felt about being there. About how badly she wanted not to be there.

Janice Garner: I wanted to back out. I felt horrible. I thought, “I can’t do this,” and I think I had a big boo-hoo there at one point.

Janice told me there was pressure on her to go through with the shoot.

Janice Garner: But how should I say that without pointing the finger at any . . .

Sarah Hepola: I don’t want to put words in your mouth.

Janice Garner: I do have a memory. We did hire a lawyer to try to, I think, get out of it.

Maybe you can hear it in her voice, but this part of the story gets a little messy. Because the photo was destined to be bigger than a page in a magazine.

Remember, the Cowboys’ poster had been a best-seller the year before. It made millions for the team. The photographer, Arny Freytag, figured there was a lot more money to be made if he sold his topless parody shot as a poster too.

It’s a little unclear when he made that decision. A story in the Washington Post, from 1979, says the Cowgirls only learned there would be a poster after they agreed to the shoot and signed contracts. That year, Tina Jimenez told the Dallas Morning News that she and the Cowgirls were, quote, “kind of tricked” into the deal. But once she learned about the poster, Tina made sure she and the Cowgirls would get a good cut.

Debbie Kepley: First they were going to offer us a flat fee, and then Tina negotiated us to get so much per poster. I think it was we were going to get 50 cents a poster, and she got 10 cents of that, and we got 40 cents.

Janice told me the pressure she felt mostly came from Tina.

Janice Garner: Tina kept telling us about how much money we were going to make, and she said each of us could stand to make about fifty grand, and that was a lot back then. What would that be in today’s dollars, I wonder?

I looked it up—that’s more than two hundred thousand dollars today. Not bad, especially when you consider that the Cowboys cheerleaders on the official poster only got paid a hundred and fifty dollars.

The Cowgirls’ photos ran in Playboy alongside a story that pokes fun at an industry that’s eager to sell sex—but pretends it’s not.

And this article is one of the more fascinating parts of this whole thing. It’s by a writer named Robert Blair Kaiser, a guy who studied to be a Jesuit priest before he switched to journalism. He spent much of his career trying to reform the Catholic Church. He supported women’s rights, and birth control. He pushed back against church leaders with too much control—and he spotted this same dynamic in the NFL.

His Playboy story describes his conversations with NFL executives, mostly men, as they decide whether to allow their cheerleaders to participate in the photo feature. Cowboys general manager Tex Schramm is among them. Schramm and the others say they want to protect the cheerleaders’ reputation. At the same time they clearly want the publicity of one of the biggest magazines around.

Kaiser calls out the Cowboys and other teams for profiting off these women’s bodies but not letting the women do the same, all while paying them no more than fifteen dollars a game.

Frank Andre Guridy: The issue is playing up very skillfully, smartly, because Playboy writers are smart.

This is Frank again.

Frank Andre Guridy: Really highlighting the exploitation and hypocrisy of the NFL. That’s what the text of the story is doing, even as the photo shoot is objectifying the women themselves. It’s the classic Playboy, right?

They got to have it both ways—criticizing the Cowboys for profiting off women’s bodies, and then getting to do it too.

The magazine hit newsstands in late 1978.

Sarah Hepola: And tell me the reaction to this issue.

Here’s Jeff Cohen.

Jeff Cohen: Well, the issue came out and it was, pardon the expression, a s— storm.

And the backlash was swift. Several of the current cheerleaders who posed in the issue were fired, even ones who had permission. The San Diego Chargettes were folded entirely.

At a league meeting, the NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle told teams to screen their candidates better and crack down on the women’s behavior off the field. The strict rules Suzanne Mitchell made for the Cowboys cheerleaders were spreading to other teams.

Jeff Cohen: I was a little surprised by the knee-jerk reaction that many of them had. But, at the same time, we also know, and we’re smart enough about this, the more stink that they made about it, the more magazines we sold. “Oh wait, that works.” And I think if it wasn’t the number one selling issue we’ve ever had, I think it was either second or third.

The fantasy that the NFL had introduced to American homes was getting difficult to manage. Nobody minded the cheerleaders being sexualized—but sexual? This was a problem.

Here’s Debbie Kepley:

Debbie Kepley: It’s like America’s sweethearts, pure, wholesome, the girl next door is representing the Dallas Cowboy cheerleaders, but we’re going to put them in these sexy little costumes and make them dance very sexual on the TV and on the field. But we don’t want you to think of them in a sexy way.

And Playboy wasn’t the only problem. A month before the Playboy issue dropped, a movie premiered in a Times Square theater.

Woman: “I’ve got a great idea. Why don’t we all work hard to raise money so we can go to Texas with her?”

Group: “Yeah!”

Bad acting, bad writing—it didn’t have much going for it.

Woman: “Well, Mr. Bradley, we’re not just washing cars anymore.”

Mr. Bradley: “You mean you’ll do anything I like?”

Except a hell of a name. Debbie Does Dallas. What plot the movie had followed a woman hoping to make a famous cheerleading squad—which, funny enough, is called the Texas Cowgirls. Ads claimed that the star, Bambi Woods, was a former Dallas Cowboys Cheerleader, which wasn’t true. But in one graphic scene, she does wear something close to that iconic blue and white uniform.

The movie could have easily slipped into obscurity. But the Cowboys sued the movie’s distributor—a company that actually had ties to the mob. A fearless Suzanne Mitchell went up against them in court, and the Cowboys eventually got all references to the cheerleaders and their uniforms cut from the film.

Ironically, the endless coverage of that trial turned Debbie Does Dallas into one of the top-selling porn movies of all time. It opened in theaters across the country. In Dallas, local authorities brought an obscenity case against the theater operators who showed the film.

TV announcer: “The movie Debbie Does Dallas supposedly traces the adventures of some high school–aged women who aspire to move to Texas and become Dallas Cowboy cheerleaders, and the movie drew perhaps as many people to the courtroom as did the trial itself.”

Along the way, the Cowboys spent one million dollars to protect their brand, an amount that could have covered the salaries of those cheerleaders for about 185 years.

And the Cowboys weren’t done in court. There was still the issue of that poster. Arny Freytag’s shot of the Cowgirls had already been on shelves for about a month, and selling well at mall stores like Spencer’s, before the Cowboys sued him too.

They claimed the poster violated their copyright and did harm to their image. They said people would assume these were current Cowboys cheerleaders posing topless.

Debbie Kepley: But Arnie’s whole thing was like, okay, was freedom of press. What happened to the First Amendment? The Dallas Cowboys can overrule the First Amendment? What kind of power does that kind of organization have?

The Cowgirls never got rich off that poster. Debbie says Playboy paid them each six hundred dollars for posing.

Freytag spent upwards of fifty thousand dollars fighting in court. He didn’t want to talk about this for the podcast. But his defense was that the photo was a parody. His lawyer told a reporter that the poster was, itself, a social statement about the cheerleaders. It was posing a question: “Are the Cowboys selling football, or are they selling sex?”

The Cowboys won. The court said Freytag failed to justify his parody claim. But Debbie has a simpler explanation for why the case shook out the way it did:

Debbie Kepley: Because it’s Dallas. You don’t go up against the Cowboys. In Texas, you don’t go up against the Cowboys. I don’t care who you are. You don’t. You can’t win.

But for the women at the center of the Playboy scandal, this wasn’t just a legal matter. It was a personal one.

Debbie Kepley doesn’t regret posing for Playboy. She’d do it again. And, actually, she did in 1980, for another feature on the women of the NFL.

Debbie Kepley: I’m glad I did it then. I wish I had, this sounds stupid, but I wish I had bigger breasts than what I had when I did it. Because, back then everybody was natural, so.

Sarah Hepola: I love that you’re happy that you did that.

Debbie Kepley: Yeah, to me, it’s like, I don’t know, I accomplished a lot of different things from being a cheerleader for two years. I got to do Super Bowl. Then I was fortunate enough to know Tina and I got to do the Texas Cowgirl thing and the Playboy thing. I’ve had a lot of opportunities like that, and it all stemmed because I was a Cowboy cheerleader.

Debbie is one of those women who has no hang-ups around nudity. She went on to star in a touring production of a play called Oh! Calcutta!, which is an erotic musical where the entire cast gets naked. But not everyone felt so at ease about the Playboy issue.

Janice Garner: I was living with my boyfriend at the time, and my mom comes over.

Here’s Janice again.

Janice Garner: And I had a feeling that she might—because she didn’t explain as to why she was paying me a visit—and we sat on the couch and she, I can’t remember how she put it, but anyway, she knew. The cat was out of the bag for sure. And she just starts to cry. Up to that day, I had only seen my mother cry once, and that was the second time that I had seen her cry. And I felt horrible. Because I loved my mom and dad. I loved them dearly, and I really hurt them. And that felt awful, and it feels awful to this day, actually.

And Janice says her boyfriend left her not long after that. In part because of the Playboy shoot.

Janice Garner: Yeah. I think he was embarrassed. He came from a really strong religious background. Posing seminude back then was really scandalous. People are half nude today just in their clothes. Nobody gives a crap, but it was a horrible thing back then.

Sarah Hepola: I have to say that’s one of the things that surprises me about this story, is how upset it makes the people around you, because to me, the images seem quite tame.

Janice Garner: Oh, sure, compared to today. Yeah, and then there’s the internet. If I got a new job, someone would eventually out me, and then my bosses would find out, and they would assume that I was promiscuous, which I wasn’t, by the way, and they’d later fire me because I wouldn’t sleep with them. I paid dearly over the years for that, the shame, the embarrassment, just the trying to hide it.

Sarah Hepola: You know, when I first learned about this story, I kind of saw it as a rebellious act, and I thought it was really cool.

Janice Garner: Yeah.

Sarah Hepola: It sounds to me like that’s not how you experienced it.

Janice Garner: No, I didn’t see it as that at all.

Janice says she wasn’t the only one.

Janice Garner: So, there were three of us that felt the same, pretty much, and had kind of the same backlash in their lives because of it, and to this day, they won’t even speak about it.

I wanted to talk to everyone in that photo. They are women in their mid-sixties now. Some of them are grandmothers. But one woman told me the Playboy issue had brought too much pain to her life, she didn’t want to reopen it.

Sarah Hepola: But you decided to speak to me.

Janice Garner: Yeah. I thought, I’m tired of hiding from it. And I can claim it now. I feel better talking about it. I can own it now and just go forward and just forget about it. I’m like, “Hey, that was a long time ago. So what?”

For the women who were Cowboys cheerleaders at this time, the double wallop of Playboy and Debbie Does Dallas was tough to take. Their rules got stricter.

And the women on the squad found themselves torn—still friends with the women who posed for Playboy, but frustrated to be mired in scandal. Here’s Shannon Baker Werthmann, who you heard in the last episode:

Shannon Baker Werthmann: There was an awkwardness because I’m seeing my friends in Playboy magazine. And I thought that the Dallas Cowboy cheerleaders were kind of like a designer brand and this was a knockoff. And I think that cheapens the brand.

And this is Tami Barber:

Tami Barber: Suzanne wanted to make sure we all knew that how awful that was. How they were disgracing all of us. And I thought, ah, not really. And I think Suzanne even, you know, tried to accentuate that in a way by saying, “Well, you see what they’re doing now. You see what mistakes they made. They’re going to regret this, blah, blah, blah.” I remember thinking, “I regret not paying my rent.”

The Cowgirls’ story reveals the tricky bargain of women trading on their sex appeal. The exposure they got came with rewards, but also pitfalls, and the line between them would keep shifting. I see this story as part of a larger battle over how we understand the beauty and the danger of a woman’s body. What do we consider shameful? What do we consider empowering?

Both sides were selling sex. But one side enjoyed the approval of preachers and parents, while on the other side at least some women were punished for what they did. The Cowgirls have been banned from any cheerleader events, deleted from the database of cheerleader alumni. But they were only following through on the tease the cheerleaders had been making for years. Here’s Frank Guridy again:

Frank Andre Guridy: So I look at the Texas Cowgirls phenomenon, I don’t see these women as folks who are just being objectified, they certainly were. They were trying to sort of, I think, get compensated for the labor that they were doing.

Both the NFL and Playboy were reaping enormous benefits from these women, and I think it makes sense that the Cowgirls wanted to break off a piece for themselves. But bucking that system isn’t so easy.

Frank Andre Guridy: Because I think there’s also a fear of, certainly at that time, of empowered women. And I think that’s what you’re seeing there too. This is a moment when feminism is making inroads in an unprecedented manner. And so, you’re seeing anxieties around that in the society, and in a weird way, the story of the cheerleaders and Playboy is really telling that story as well, the tremendous anxieties about women doing things that they shouldn’t be doing.

You can still see these same issues playing out in football today. In 2018, a New Orleans Saints cheerleader posted a photo of herself on Instagram, in a lacy one-piece—and the team fired her.

The Cowboys cheerleaders have cut women from their training camp too, after coaches discovered racy pictures they took before they tried out.

In an industry trying to balance old-fashioned morals and guilt-free voyeurism, it would continue to be a tricky question—when these women get to be sexy and when they do not. Who gets to decide? And who gets to profit?

Next time on America’s Girls:

Sarah Hepola: So, then where does the uniform come from?

Dee Brock: Well, it really came from my imagination. I drew this sketch of what I thought it should look like.

Sarah Hepola: Okay, can you respond to that?

Paula Van Wagoner: Um, it just didn’t happen that way.

- More About:

- Sports

- Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders