Quarantined at home in San Marcos, Texas Monthly staff writer Christian Wallace has spent the bulk of his week working the phones, talking to energy experts and oil executives for next week’s special edition of Boomtown, what began as a ten-part Texas Monthly podcast series documenting record-breaking oil production in the Permian Basin. But while Boomtown was largely focused on an oil boom that stood to reshape the world’s climate, economy, and geopolitics, suddenly the crossroads of overproduction, geopolitical instability, and the COVID-19 pandemic have signaled what might be the beginning of a game-changing, potentially historic oil bust. For a few hours on Monday, prices for May delivery of a barrel of West Texas Intermediate crude oil went negative, to a record-setting -$38. To sell the same barrel that started the year trading above $60, you’d now have to pay someone nearly $40 to take it off your hands.

Subscribe

“It’s incredible,” says Wallace, who grew up in Andrews, Texas, and spent a year working as a roughneck. “Leading up to this, at the same time that you had unprecedented demand destruction with the pandemic locking down almost the entire world population, jet fuel down 90 percent, and gasoline sales down over 30 percent, you have a price war starting with Saudi Arabia and Russia that opened up the floodgates of more oil. So you already had a saturated global market and then you had more oil coming in at a point of devastating demand destruction.”

By Thursday morning, the June contract for WTI was selling for about $18 a barrel, which Wallace’s research for Boomtown suggests isn’t close to most producers’ break-even points. Even before Monday’s historic low, the Texas Railroad Commission, which regulates the Texas oil and gas industry, was considering the ultra-rare step of cutting production. But after hearing ten hours of testimony last week, they ultimately decided to revisit the issue in early May.

On our podcast, recorded by phone Thursday afternoon, Wallace walks us through the arguments for and against cutting production. We also discuss whether supply and demand equilibrium is possible in a pandemic and the toll on the Permian Basin and Houston of the unprecedented oil sector layoffs and furloughs of the last few weeks.

Three takeaways from our conversation:

When Wallace was reporting his June 2019 Texas Monthly piece “The Permian Basin Is Booming With Oil. But at What Cost to West Texans?” and later, for Boomtown, there was already concern that Texas’s oil boom was being built by producers mired in debt.

“We had a brilliant business journalist on the podcast named Bethany McLean, and she wrote a book called Saudi America that really took a hard look at the finances that had propped up the shale industry. With the U.S. shale boom, we’ll often talk about how the innovation was there—horizontal drilling and the hydraulic fracturing techniques that made it easier to access this oil that’s trapped in really tight shale formations. But the other side of that is it’s still expensive to extract. So after the 2008 financial collapse, you had tons of cheap debt available. You had low interest rates and you had private equity who are looking to turn a profit. And they took a bet on the shale industry. And that has proven over the last ten years or so to not have been that great of an investment. The sixteen largest publicly traded fracking companies, about five years ago, when oil was at $100 a barrel, blew through something like $80 billion of cash without returning dividends to their investors. So over the last year or so, we’ve seen a lot of these debts start to come due and investors getting impatient. And so before the COVID-19 outbreak, we already saw a lot of the players in the Permian and elsewhere starting to cut back on their budgets, on their exploration activities, and what they were planning for the year ahead … but of course, no one could have predicted a global pandemic at the same time as a price war between the second and third largest oil producers in the world.”

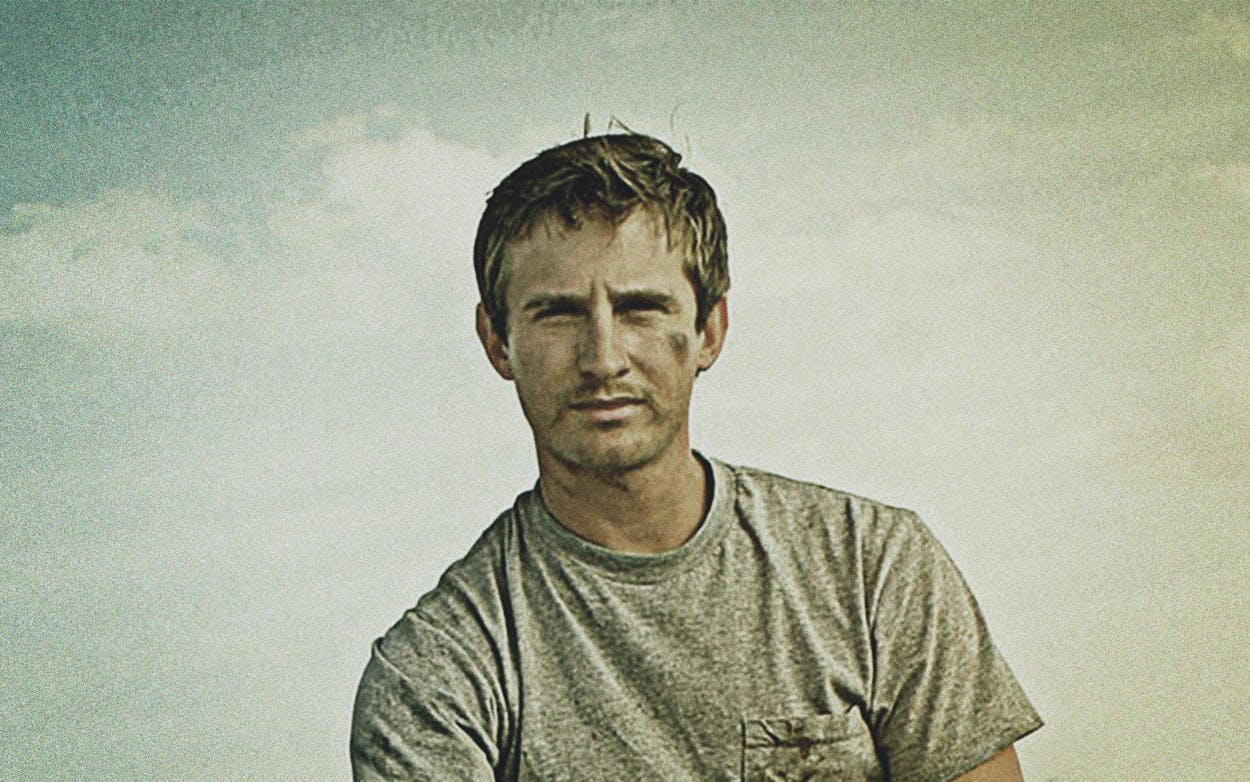

Like his father, who started working in West Texas oil fields while he was still in high school, Wallace spent 2012 roughnecking on a pulling unit—what he says is essentially a smaller drilling rig used to work on wells that have gone offline. As such, he’s careful to draw a distinction between what he calls “Big Oil, capital B and capital O,” and the people they employ.

“My little town lives and dies by the price per barrel of oil. And it has since its inception just over a hundred years ago. I grew up seeing the faces of the oil field—it’s not BP executives, it’s not guys in skyscrapers in Midland or J.R. Ewing from Dallas. I see my friends’ parents and, for a while, myself. It’s my community, and I see the bruises from working on the rigs and the oil underneath everyone’s fingernails when you go into the diners at lunchtime. There’s 10 million people that this industry employs, and the industry has a terrible public track record environmentally and, recently, economically. A lot of that has been greed. Um, one thing that’s happened during this last boom, the price was pretty low, but we were producing more oil than we ever have before. We became the world’s largest producer of oil in early 2019 and largely because of the oil that was pumped out of the Permian Basin in West Texas and Southeastern New Mexico. And so people got greedy. And so we started doing things that were very environmentally unsound. So when we talk about Big Oil, there is definitely a reckoning to come for the industry in that way. But I think we should also be aware of the men and women whose livelihoods depend on it and who will honestly risk life and limb to provide for the energy needs that you and I benefit from every day.”

Wallace says that while 99 cents a gallon gasoline looks good for consumers on paper, it could actually have devastating trickle-down effects.

“I’ll definitely go fill up at that price, but we could end up seeing a flip of everything we’re talking about right now. I’ve heard an argument that during this downturn or this bust, whatever it ends up being, we could lose up to 80 percent of our oil and gas producers in America. They would go belly-up, they’d go bankrupt, they would consolidate. We’re obviously going to produce less oil because of the drop in demand. And so we were going to see a lot less oil eventually, and when the demand does come back, depending on how quickly it ramps up, we could see oil shoot way back up because there’s fewer people out there to get it out of the ground. With fewer companies and fewer investor dollars willing to risk getting it out of the ground, we could end up swinging back the other way with oil prices.”

(Excepts have been condensed and edited for clarity.)