Daniel Lanois is one of the most successful and singular producers in the history of recorded music, the collaborative genius behind U2’s The Joshua Tree and Achtung Baby, Bob Dylan’s Oh Mercy and Time Out of Mind, and Emmylou Harris’s Wrecking Ball. On this episode of One by Willie, he talks about the landmark record he made with Willie, 1998’s Teatro.

Subscribe

(Read a transcript of this episode below.)

Recorded essentially live over four days in an abandoned movie theater in Oxnard, California, a small farming community outside Los Angeles, Teatro sounds like no other album in Willie’s massive catalog. The soundscape is moody and mystical, laid under a collection of vintage Willie compositions plus five new songs he’d recently written, one Django Reinhardt cover, and another—“The Maker”—that Lanois had written himself.

For our discussion, Lanois opens with one of the new songs debuted on Teatro, “I’ve Loved You All Over the World.” But then the conversation itself starts to float, with Lanois touching on Cuban dance clubs, Texas honky-tonks, Mexican movie houses, and the way recording musicians in the same room, playing together, grows the creative spirit . . . before he lets his mind fully unwind while we listen to Willie play guitar.

We’ve created an Apple Music playlist for this series that we’ll add to with each episode we publish. And if you like the show, please subscribe and drop us a rating on Apple Podcasts or wherever you get your podcasts.

One by Willie is produced and engineered by Brian Standefer, with audio editing by Jackie Ibarra and production by Patrick Michels. Our executive producer is Megan Creydt. Graphic design is by Emily Kimbro and Victoria Millner.

Transcript

John Spong (voice-over): Hey there, I’m John Spong with Texas Monthly magazine, and this is One By Willie, a podcast in which I talk each week to one notable Willie Nelson fan about one Willie song that they really love. The show is brought to you by Still Austin craft whiskey. This week, we talk to one of the greatest, most innovative producers in the history of recorded music, Daniel Lanois. He’s the genius behind U2’s The Joshua Tree, Bob Dylan’s Time Out of Mind, Peter Gabriel’s So, and Willie’s own landmark 1998 album, Teatro.

Daniel’s going to focus on one of his favorite songs on the album, “I’ve Loved You All Over the World.” But then his mind will start to float to Cuban dance clubs, art that exists only in shadows, and the way that U2 tries to summon Willie when they’re writing songs. For real. Oh, and a quick aside: Daniel likes to record in unorthodox locales. He and Brian Eno famously made U2’s Unforgettable Fire in an old Irish castle. Well, he and Willie made Teatro in an abandoned movie house in Oxnard, California. If you want to look at what that was like, maybe after the show get over to YouTube and check out the videos that Wim Wenders shot of Willie, Daniel, Emmylou Harris creating the songs on Teatro. They’re stunning. Let’s do it.

John Spong: We start where we always start: What is so cool about Willie’s “I’ve Loved You All Over the World”?

Daniel Lanois: I listened to the track a couple of days ago with Wayne, and I was surprised at how stark it was. It has no bass, and the drums sound like they’re rattling. They have the sound of rattling bones, as if it’s some kind of a marionette show. And you can really feel the presence of people in the room. And we got things in one or two takes, so it really shows in this, because it is about as far away from production as you can get. It’s just this lovely “Clickety-click, de click, de click,” as if the skeletons are coming out of the closet, and they’ve become drummers.

And so it brought back a lot of memories of that setup, which was a wonderful setup because we wanted the place . . . It was a nice old theater, by the way, an old Mexican theater. And so no windows. It’s a cinema house. And we had some nice risers set up for Willie and Emmylou and the drummers. So we had a nice time setting it up like a club, and it sounds as though the fun that you’re hearing in the track was definitely in the building at the time.

John Spong: It was in the room. Oh, I love that. Well, that’s perfect. Let’s spin it. And one of the things that kills me about this is, this is one of those rare Willie songs that shows up only on this one album. If somebody wants to experience “I’ve Loved You All Over The World,” they got to go to Teatro. So go with me now to Teatro . . .

[Willie Nelson singing “I’ve Loved You All Over the World”]

Daniel Lanois: Yeah, that’s quite a track, isn’t it? My goodness.

John Spong: Yeah, yeah.

Daniel Lanois: I was trying to figure out what it was all about because I know there, on the record, I might have gotten confused, because I know there was one record about his kids at the time, carrying a photograph around the world as Willie traveled, but he always kept a picture of his kids near his heart. But I think this is probably all about love of music. And “I’ve loved you all over the world.” The pilgrimage never stopped for Willie.

John Spong: Right, right. And there’s the great line too, “And you loved me sometimes.”

Daniel Lanois: Yes. That’s the curious twist in the story—”And you love me sometimes,” as if to say, “You’re always there for me at the right time. Music, my savior.” So let’s say I’m right about it. It’s about music. That’s pretty good.

John Spong: I like that. I’m for that; I’m for that. And Lukas and Micah, who you just mentioned because that is, that’s the other song on the record, or one of the other songs on the record, “Everywhere I Go,” which is the song about the photograph in his heart. That’s them, and they’re [nine] and seven when this is recorded, and they’re there with you, mom’s there, Annie, the whole family. Yeah?

Daniel Lanois: Yes, the whole family was there at the Teatro. Yeah, the boys were running around like Rugrats and loving music and every aspect of it. And it was a very sweet locale because you can just imagine the stories in the walls of such a cinema. And it was very simple.

Willie waited in the parking lot on his bus, and I worked up the band for the next song. And then I’d go out and get him, say, “Okay, Willie, we’re ready for your close-ups now, Willie.” And he’d come in and we’d do one or two takes, and that was it. And it shows in, I think, the record has a lovely, innocent feeling about it. We did it in four days, so it will always have a little bit of quickness in its step. But I think people hear this record and they feel that it’s the real deal, that we weren’t relying on too much studio trickery to get the thing across.

John Spong: Yeah. So, it’s ’98. How did you get the gig in the first place? How did you wind up producing a Willie record?

Daniel Lanois: I got a call from Mark Rothbaum, who manages Willie, a great man, and that was the introduction. Of course, I always—like everybody, I grew up listening to Willie, but I’ve never really gone after work. I just respond to invitations. So that’s what it was. It was an invitation. There was obviously an alignment with Emmylou Harris, and she sings on the record. And man, she just watches him like a hawk, because his phrasing can be different from one take to the next, so you really have to watch Willie if you’re going to harmonize with them.

But it was a nice time of concentration because there were a few back-to-back projects at that time. I was also working on Bob Dylan’s Time Out of Mind record; it was started and finished at the Teatro. Billy Bob Thornton’s Sling Blade movie, the soundtrack was done in there, in that cinema. So there was a chapter of creativity that we were living through at that time, and Willie was smack-dab in the middle of it.

John Spong: And—if I read, from the time, from back then, once y’all decide you’re going to do this, he says, “Well, okay, here’s a hundred of my songs, if you want to pick some.”

Daniel Lanois: [Laughs] No, no, no. I did a bus ride with Willie, I think it was from Vegas to California, and we talked about what we were going to do. So it was in conversation. It wasn’t “Here’s the vault. Go to work.”

John Spong: Well, but it’s great because so many of the tracks on it, of the songs, are really vintage, early sixties Willie, but then there are these [five] new songs. This one, there’s the instrumental “Annie,” because Annie and he had been together for ten, twelve years at that point. They’ve got the boys. It’s vintage Willie, but it’s also brand-new Willie, and all of a piece.

Daniel Lanois: Well, you’re right about the content ratio, let’s say. But more important than that is we found something in the making of that record that allowed it to stand out. And even for people who were familiar with the older titles, to hear them—I guess you could say it was a live rendition of sorts, but in a very controlled environment. So you get all the spontaneity of fast takes or first takes, but with attention to details on the sound and proximity of the people.

And I can remember spending a good amount of time with Aunt Bobbie to introduce her to my little Wurlitzer piano and then a left-hand cello system. So I gave her two sounds to work with. I’d say, “Bobbie, you can play a regular piano part, first part of the song, you get to the next verse, then you can go to cellos, and then combine the piano and the cello for the next section and so on.” It was just a tiny little twist in the setup, and she really had a great time with it because it was something fresh for her.

John Spong: And there’s that song, which is another new one for this record, “Somebody Pick Up My Pieces”—I actually heard you on an interview recently listening to that song. And there’s no bass—as there is through very little, through much of that album, no bass guitar—but she’s doing it with her left hand on either the Wurlitzer or the cello. It’s so cool and it’s so sophisticated, and it’s such a nice touch on that track in particular.

[Willie Nelson singing and Bobbie Nelson playing “Somebody Pick Up My Pieces”]

Daniel Lanois: Well, I’m glad you mentioned that because obviously the left hand of the piano, if there’s a bass player in the room, then you have to put some thought into where you’re going to go with your left hand, because you don’t want clashes in the bottom end. And so there’s a freedom that I heard by not having bass in the room. It meant that we were doing the rumba to other parts of the arrangement.

And the drummers, I have to say, were just terrific. Victor Indrizzo and Tony Mangurian, I hired those two guys because one of them’s a lefty and the other one’s a righty, so we had them sitting in one big kit.

John Spong: Which is insane! One drum kit, two drummers. But if it’s a righty-lefty thing . . .

Daniel Lanois: That’s it.

John Spong: The hi-hat’s over here and it’s over there . . . and it works, right?

Daniel Lanois: That’s right, yep. So, uh . . .

John Spong: But how did you get that idea? Because it wasn’t like that rhythm was necessarily a Lanois signature or trademark, at the moment. It brings this Latin feel . . . because you don’t hear it as much on the song we just listened to, but you hear it through the rest of the album in a very pronounced way. It’s such a big part of the flavor of this, of Teatro. How did you get that idea?

Daniel Lanois: I wanted a shift in my career. I wanted to be known for rhythm. I said, “This is it. Let’s bring in some top-level Latin drummers.”

And no, I’m joking with you, but of course, you know what it was? When I asked Willie how he got started, he says, “Well, we were a dance band in Texas, and we played a lot of late-night spots, little dance halls,” and the more he talked about it, I realized that it might be nice if this record had a rhythmic slant to it.

So we squinted a little bit and felt as though we were in Cuba, and because the place had no windows, so we got a chance to create our own little setting there. So we busted out some Cuban cigars, and there was this whole thing about the dance club and sweaty nights, cheek to cheek, people have a good time, forgetting about their troubles and dancing the night away. So that’s what we wanted for that record.

John Spong: And Willie even talked about that. He said, “They’re some really bleak songs.” But that rhythm makes it something you can dance to. Willie said it was dark, but very bright. You know?

Daniel Lanois: Well, welcome to art. We don’t want one dimension with art. We want to know what’s happening in the shadows of a painting, don’t we?

John Spong: Yeah.

[Willie Nelson and Emmylou Harris singing “I’ve Loved You All Over the World”]

John Spong: You’ve mentioned the theater a couple of times, and if we could go a little further into that, because you have this history of putting studios where they previously were not—you know, of willing studios into being. Can you talk about that room? I mean, it’s in Oxnard, California. What’s Oxnard, California? And what did you and Mark Howard do in that place? Your engineer, partner, production partner.

Daniel Lanois: It’s a place that I found. I took a drive with a friend of mine from L.A. We were listening to some various mixes and whatnot, and I saw the sign For Lease. And it was far enough . . . For anyone who doesn’t know Oxnard, it’s an agricultural basin, really. And so it’s a fascinating place, because there’s a lot of agricultural workers that live there, some of them migrant, I’m assuming. And so there was something about the place that I took a liking to, because it was the same as it ever was. Across the street was a nice little Mexican restaurant, open all day, all night. That’s where we ate. Army surplus place was next door. That’s where we got all our soundproofing.

John Spong: Oh, really?

Daniel Lanois: And then Gordon’s Western Wear was next door to that, and that’s what we dressed in. It was just very sweet to find something seemingly still living in the past, in the nicest possible way. And so why not do it in a theater? I always liked being in a place where entertainment had already happened. It’s a nice feeling that you get when you play a club that, if Jimi Hendrix has stood on that stage, then it’s still rumbling through the stage and the rafters. And if Santana was there, I feel better about my guitar playing, and so on and so on.

John Spong: Of course. And so you leave some seats in; the soundboard is in the room.

Daniel Lanois: We did build. Removed a section of the seats and built a platform, because it’s a sloped floor, obviously, because it’s a cinema. You walk into the movie, you’re kind of . . .

John Spong: Down?

Daniel Lanois: You’re walking down. So we had to defy the slope, and we built a stage there for all the equipment, quite a bit. And that’s where everybody sat and played, so it was all one big happy family.

The orchestra pit, let’s call it, was disused, but could accommodate projectors and lighting equipment, projecting images onto these big weather balloons that we had, we bought from the surplus joint next door. And these things inflate about, let’s say, fifteen feet across, and they become translucent, partly opaque, and you can project right through them. It’s the most beautiful, cheap trick. So, we had these giant crystal ball things in the Teatro.

It was just a lot of fun. You might think of it as an art installation, really, now that I think of it. And we had a lot of lovely times there. It’s just a nice reminder that the place had something in it that promoted performance, and that’s what shows up in the Willie Nelson record.

John Spong: And Rothbaum, Mark, described that to me, because he said, “Daniel and Mark Howard’s motorcycles are out front, and you walk past those to get in. And then there’s the disco ball, there’s Tiffany lamps, there’s marble tables, there’s beautiful guitars in the old theater seats. There’s these great old Mexican movie posters on the wall.” He always talks about the El Macho poster in the hallway when you come in. And he said that this was the sexiest, most romantic art he had ever been part of and added, “And I worked with Miles Davis, man.”

Daniel Lanois: Yeah, there was something beautiful about these old Mexican posters. A lot of them were just the old movie posters, movies that they were showing there from . . . It had closed down for a long time . . .

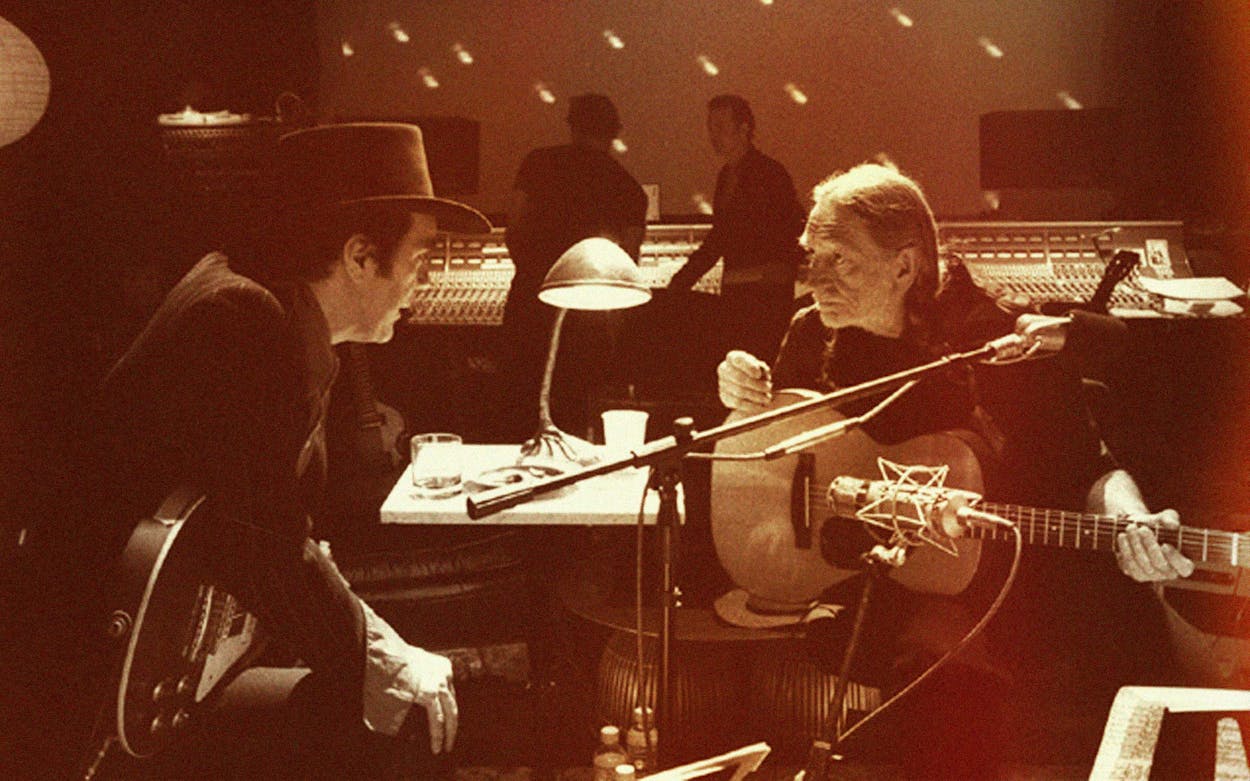

John Spong: And then this idea that you touched on a second ago: everybody in the same room; everybody going through this experience together. In the footage that Wim Wenders shot, after y’all were done recording, when you played the record through again or performed it again, Emmylou and Willie are knee to knee. She’s on his left. And then just on his right, a little further away because you’re not singing with him, but there’s you. And then just over your shoulder are Tony and Victor. And Mickey’s in the corner. Everybody’s right there experiencing this thing together. And I think, what have you said, that when you separate people, you block intuition?

Daniel Lanois: Well, proximity is a friend to communication. I mean, if we’re sitting at a small table, and it’s a quiet spot, then we’re going to have an intimate exchange. But if I’m in another room talking to you on a camera, that’ll be a little bit different. We certainly won’t be having sex.

John Spong: There’s nothing I can say!

Daniel Lanois: I’m not suggesting that you and I are about to do this at a table for two. I’m just trying to create a difference between being close to someone and being not close to someone.

John Spong: I feel so far away from you right now.

Daniel Lanois: Well, the Willie record certainly resonated with that idea. Just put people close together as if they’re on stage. It was not that mysterious a thought.

But people close together, that has worked very well for me all along. And we made Emmylou Harris’s record, a record called Wrecking Ball, roughly the same time; it was in the nineties. And we had nice results grouping together . . . Emmy on one chair, me on the other, Steve Earle on the third, and then Lucinda Williams on the fourth. We were crowded together as if we’re sitting at a little tea ceremony. And when people are that close together, they automatically balance.

I mean, I’m not suggesting it’ll work for some kind of heavy metal music or anything, but we’re just singing folk—country and folk songs here. It’s okay. They’re kitchen performances, let’s call them. And so, how are you going to record something like that? Well, stay in the kitchen and bring in the mics. So in this case, stay in the Teatro and bring in the mics.

[Willie Nelson and band playing “I’ve Loved You All Over the World”]

John Spong: Willie plays a Gibson guitar on this as much or more, maybe, as he plays Trigger, his old signature Martin guitar. Was that your idea?

Daniel Lanois: Willie played my ES-330 Gibson guitar. It’s an early sixties instrument. Very nice. He played it, I think, on two songs. Let’s not exaggerate here. So it was not a replacement for Trigger at all. I just thought that it might give him an opportunity to go slipping and sliding on something else, which . . . He’s a very spontaneous player—one of my favorite guitar players, actually. And so just as an experiment, we put the ES-330 in his hands, and it worked out just fine.

John Spong: What do you like about his guitar playing?

Daniel Lanois: His guitar playing is like his voice, really: unexpected phrasing. And he’ll go to a certain melody or a certain riff or a certain moment of expression, purely as a response to how he feels in that split second. So I like the wayward, unexpected aspect of his phrasing, by guitar and otherwise.

John Spong: It’s interesting. I’ve been listening so much more closely to this record than I have in a while. And one of the things that stands out: it is very much a guitar record, in my mind. And part of that, his guitar is—it’s different than on other records. So much of this record is singular just because of the world y’all created in the theater that you just described. But his guitar playing is distinct too. And at times, especially on a song like “My Own Peculiar Way”—which is an old, old Willie song; I think Perry Como had the first hit on it in the sixies, right?—it sounds so much more flamenco. Or you can hear the Mexican influence in what Willie does so much more plainly on some of the guitar playing here, and I wonder if that was in response to this rhythmic setting you created that is distinct from what he normally does.

[Willie Nelson playing “My Own Peculiar Way”]

Daniel Lanois: I think you’re right. The drumming angle that we use on Teatro promoted . . . it pushed the Django Reinhardt button a little bit for Willie, because he was able to get in there and respond to the exotic rhythms as provided by the drummers.

John Spong: Smart. Oh, another moment on there . . . Well, goodness, “I Never Cared for You,” which Lukas talked about on this podcast a couple of weeks ago, for Willie’s birthday. The album opens with “What Now My Love,” right? Or the Django, “Où Es . . . Où Es-Tu, Mon Amour?”

Daniel Lanois: “Où Es-Tu, Mon Amour?” Like, “Where are . . . where art thou, my lover?”

John Spong: Yeah. Well, actually, do you want to listen to a moment of that? Do you have the bandwidth?

Daniel Lanois: Yeah, man. Sure.

John Spong: Let’s do it.

Daniel Lanois: Blast it, man.

John Spong: Is that coming through?

Daniel Lanois: No, no.

John Spong: Just . . . Ah, I can’t do it, man.

Daniel Lanois: Well, just describe it to me.

John Spong: Describe it. Okay, so yeah . . . It’s eerie. It’s really eerie. The album opens with this really . . . I guess it’s a Wurlitzer. It’s this great electric piano. And then Willie’s guitar comes in, and it’s so ethereal. But then it goes into “I Never Cared for You.” And on “I Never Cared for You,” that’s a familiar Willie song to many of his fans, but the Cubans come in—as Mark Rothbaum calls them—Victor and Tony. And they come in, and it’s just immediately this completely different thing than you’ve ever heard Willie do before. And as Rothbaum says, “The sequence of the album and the album itself is perfect. It takes you on this journey.” And this is the start of the journey. It’s really—it’s really something.

Daniel Lanois: Okay, Wayne’s just dialing it up here. Isn’t it interesting, the amount of . . . Okay, here we go. Yeah.

[Willie Nelson playing “Où Es-Tu, Mon Amour?” (“Where Are You, My Love?”)]

Daniel Lanois: Well, that’s so beautiful. Hi, this is Daniel Lanois, all the way from Toronto, coming to you at the end of the needle. And as you can hear, the great Willie Nelson—as a youngster, inspired by Django Reinhardt. And we have a term in Ireland, when I’m working with U2: “Should we include a ‘Willie chord’?”

John Spong: Do you really?

Daniel Lanois: “A Willie chord!” Which means it’ll be an augmented . . . or a diminished . . . or something a little unusual. So there’s terminology out there that exists in the world of composition.

John Spong: Oh, I love that.

Daniel Lanois: “Shall we include a Willie chord?”

John Spong: That’s fantastic.

Daniel Lanois: But as I’m hearing this, it’s so beautiful and exotic. It stops you in your tracks, slows the heart rate down, and it makes you want to live forever. Isn’t that nice? And dance cheek to cheek. And so even though some of the subject matters are a little on the dark side . . . as we mentioned earlier, a little shadow’s okay.

John Spong: Yeah. You can’t get away from it. Acknowledge it.

Daniel Lanois: So in this case, Willie’s doing this really unusually long intro, and the drummers are watching Willie. I probably count it in, let’s see if I do a good job, then it goes far out, and then it escalates chromatically, and it looks for its ultimate plateau. And there it is, the emotional moment of explosion. We’re almost there. Yes. And the moment has come, as we slide down the waterslide, and we land in the black lagoon, and it’s going to get dark. Here it comes. Everybody waiting . . . All right, Danny. Almost . . . almost . . . okay, okay. Here it comes, and it builds, and it builds . . . and it builds . . . and it builds . . . and finds its home. Three, four, three, four. [Laughs] It never returns. I got to push something else here.

John Spong: [Laughs] Hit track two.

Daniel Lanois: After all that, it never got to it. That was funny. That was some of my best free-form poetry right there. Okay. So, make sure you include that. That was kind of fun.

John Spong: That was magical. But then it’s like, “Dom . . . dom . . . dom . . . dom, dom . . . dom . . . dom . . . dom,” and then the rhythm starts. And it’s like we are on uncharted—this is a planet we’ve never been with Willie before.

Daniel Lanois: That’s right. Because it was Bobbie that did the Wurlitzer. “Dom . . . dom . . . dom . . . dom.” Yeah, that’s right. [Percussive scatting] Okay. It’s nice because, I mean, it was said in fun initially, with the drummers, that we wanted to take things south of the border a little bit, to Cuba or otherwise. And everybody thought that that was a fun picture to paint. And we stuck with it.

[Willie Nelson and Emmylou Harris singing “I Never Cared for You”]

John Spong: I don’t know that this would’ve even registered with you, but do you remember what—or do you pay attention to the reaction to records when they come out? Do you remember what people thought?

Daniel Lanois: I’ve been getting comments about that record all along. But what means most to me is that the record has lived on nicely, and it’s become some people’s favorite record from Willie. And I think people appreciate that it doesn’t have . . . It’s not suffering from any kind of studio-itis. It was a captured moment. It’s a Polaroid snapshot of an album, rather than something that got labored over . . .

John Spong: And it turned into a real relationship with Willie. When I was at the ninetieth birthday stuff at the Hollywood Bowl last month, you were onstage with his son Micah.

Daniel Lanois: Yes, I’ve become an honorary family member of the Nelson family.

John Spong: How’d that happen?

Daniel Lanois: Well, I mean, obviously Teatro was a nice rock to stand on. Once we finished that, then everybody thought, “Okay, now we’re nicely saddled up here. The record has its dignity intact, and people are enjoying it.” So, it meant that, having done that album, that we could hang out a little bit. And I got to know Micah and Lukas some along the way, and we always thought we would do some recording together, and I’ve started that with Micah.

John Spong: Oh, cool.

Daniel Lanois: And we’re writing some songs together and putting a record together. So there’s something sweet about how we’re continuing with the—Teatro was the beginning, and now more music has come our way. And I had a nice conversation with Annie at the birthday party, and she said, “We are a tribe.” And I thought, “Oh, that’s a nice way to look at it,” because you can leave the madness of the world outside and go to your tribe, where the values don’t shift too much and the responsibilities are pretty much the same as they have always been. And it’s a nice way to look at it.

John Spong: Yeah. And did you record some with Willie recently when you saw him? I’m wondering why this is the only record we have, but I know that there’s also a lot of Willie in the vault and places. Is there other . . . are there other Willie-Lanois recordings?

Daniel Lanois: Well, Willie was—

John Spong: At least on the horizon?

Daniel Lanois: Willie was just in my studio recently.

John Spong: What’d you do?

Daniel Lanois: He did a cameo on this record that I’m working on with Micah Nelson.

John Spong: Great.

Daniel Lanois: He shows up on two tracks. So it was lovely to see him. And as he was leaving, he said, “Well, what do you think, Daniel? Should we do that other record now?” As if to say one was not enough. I said, “Of course, Willie.” And then I talked to Rothbaum. Apparently, we’re slotted for October.

John Spong: That’s magnificent. When you mentioned U2 and Willie chords . . . I grew up in Texas. I’ve never not known a world with Willie in it, right? And so he’s just Willie, and I mean, I would see him at the hamburger place growing up. Honestly. There was a hamburger place down the road called Willie’s, had no relation to him, but I even asked him one day when I ran into him—he goes, “Well, where are you going to go eat your hamburgers? I go to Willie’s.” And so, Willie.

But when I realized, at some point—and I think it was actually through Dylan—that these icons consider this person I consider one of us one of them. That U2 has Willie chords . . . I don’t even know where the question is in there.

Daniel Lanois: Well, what you’re hinting at here is everybody loves Willie. And Willie therefore has become an ambassador to many. Bikers love Willie. Grandmothers love Willie. Babies love Willie. I love Willie. Everybody loves Willie. And how many artists have we had that had that? Maybe Bob Marley had that, you know?

It’s a curious position to occupy. And it’s quite an opportunity to, if you look at such an artist as somebody who can reach a lot of eardrums from all walks of life, so what are you going to sing to those eardrums? And so it gets me thinking about October. What shall we say in October?

John Spong (voice-over): All right, Willie fans, that was Daniel Lanois, talking Teatro and “I’ve Loved You All Over the World.” A huge thanks to him for coming on the show, a big thanks to our sponsor, Still Austin craft whiskey, and a big thanks to you for tuning in. If you dig the show, please subscribe, maybe tell a couple friends, and visit our page at Apple Podcasts and give us some stars. And please also check out our One by Willie playlist at Apple Music.

Oh, and be sure to tune in next week to hear Dr. Brené Brown—who in the press gets called a researcher, an author, and a storyteller, but friends and fans, I’m pretty sure, just call an inspiration—talk about one of the most important songs Willie’s ever sung, “Amazing Grace.” We will see you guys next week.