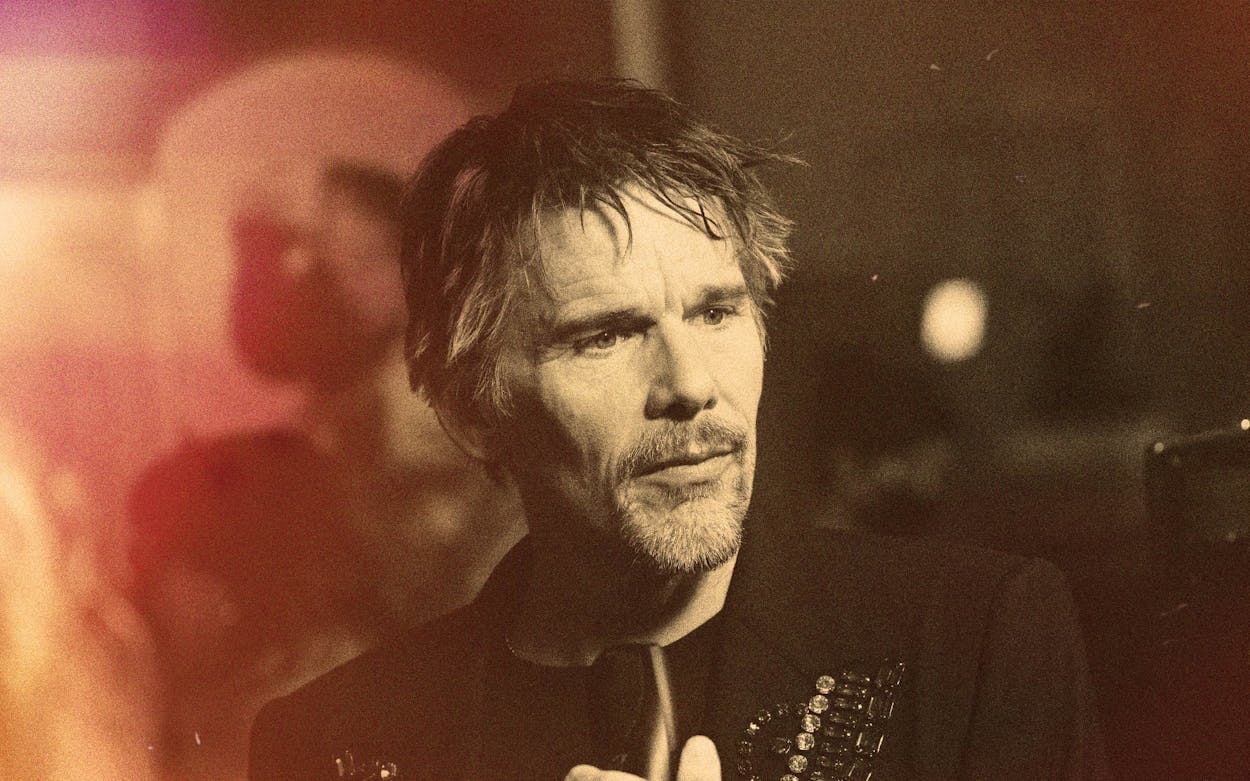

Ethan Hawke was just five years old when, in 1976, his father took him to Willie Nelson’s Fourth of July Picnic. It was a huge moment for Hawke, not just because it was his first concert, but because of the way Willie’s music would go on to connect him with his dad as he was growing up.

Subscribe

(Read a transcript of this episode below.)

On this week’s One By Willie, the acclaimed actor, writer, and director—and deep-thinking Willie nerd—talks about “Too Sick to Pray,” a meditative hymn from Willie’s beautiful, pin drop–quiet 1996 album, Spirit. Hawke calls Spirit one of his top five Willie albums, marveling at the utter simplicity of the music, but focusing more on its seeking, salvific message and the pivotal role it played in Hawke’s life when he became a father himself.

It’s a wide-roaming conversation, with digressions on Bob Dylan, Henri Matisse, Johnny Cash, Dead Poets Society, and, yes, earlobes—that Hawke ties up at the end with thoughts on why a Willie Nelson biopic needs to be set not during the Nashville struggles of the sixties, nor the Austin breakthrough of the seventies, but in the here and now.

We’ve created an Apple Music playlist for this series that we’ll add to with each episode we publish. And if you like the show, please subscribe and drop us a rating on Apple Podcasts or wherever you get your podcasts.

One by Willie is produced and engineered by Brian Standefer, with production by Patrick Michels. The show is produced by Megan Creydt. Graphic design is by Emily Kimbro and Victoria Millner.

Transcript

John Spong (voice-over): Hey there, I’m John Spong with Texas Monthly magazine, and this is One By Willie, a podcast in which I talk each week to one notable Willie Nelson fan about one Willie song that they really love. The show is brought to you by White Claw Hard Seltzer.

This week, we visit with four-time Oscar nominee Ethan Hawke, who will talk about Willie’s song “Too Sick to Pray.” You probably know Ethan as a movie star, stage actor, director, and writer, but he also happens to be one of the most serious students of Willie Nelson that I have ever talked to. So he’s going to talk not just about how Willie’s songs tied him to his dad when he was a kid, but how the deep spiritual undertones of “Too Sick to Pray” and the album that it first appeared on, Spirit, from 1996, shaped the way that Ethan has raised his own family. Sprinkled in will be digressions on Bob Dylan, Matisse, Johnny Cash, the Dead Poets Society, and earlobes. Oh, and he’ll also describe how he’d make a Willie biopic and why he’d set it not during Willie’s struggles in Nashville in the sixties, or his breakthrough in Austin in the seventies, but in the right here and now. So let’s do it.

[WIllie Nelson playing “Too Sick to Pray”]

John Spong: So, tell me about “Too Sick to Pray.”

Ethan Hawke: Well, the thing is about “Too Sick to Pray” is that that whole album, Spirit, I don’t know, it’s right up there on the Willie Nelson top five, as I’m concerned—as far as the most representative of the best that Willie Nelson has to offer. I mean, nobody else in the world would make Red Headed Stranger, Teatro, or Spirit. I mean, they’re just quintessentially something . . . one of my favorite Bob Dylan quotes is, somebody asked him what he has left to do, and he said, “Well, I’m still trying to make a record as good as Red Headed Stranger.“

John Spong: Oh, wow.

Ethan Hawke: Yeah. I always loved that quote, because it does live up there, as far as being a fully, completely realized artistic expression. Something about it is singular in its expression. It’s not like anybody else. He’s not imitating anybody else. That’s Willie Nelson. At his different ages, he has different high-water marks. And for me, I felt Spirit . . . what year did that come out? That was like the early nineties?

John Spong: Ninety-six.

Ethan Hawke: Ninety-six. That’s right. Spirit came out the same year that my daughter was born, or, I got it the year my daughter was born. I guess it came out a little bit before. During the whole pregnancy, you know, it’s such a moment, in your life, of transition. You feel like, yes, the baby is in a cocoonlike state and about to be a butterfly, all that kind of metaphor, but the parents are too. Especially with your first child, you feel . . . and for me, it was kind of a connection to the Red Headed Stranger, because Red Headed Stranger was so pivotal in my childhood. When my parents got divorced, my dad listened to Red Headed Stranger over and over and over and over and over again.

John Spong: Oh, wow.

Ethan Hawke: In 1976, he took me . . . We drove from Fort Worth to Austin for the Fourth of July picnic. And I mean, I’m telling you, my dad had that on LP. He had it on eight-track. He played it on the piano. He had the songbook on his piano, and he’d be playing all those songs, and I felt . . . He was probably only twenty-six at the time, but he seemed like an old man to me, you know, what a grown man was. And he was in a lot of pain, my dad, and this album was a real source of healing for him. I can’t say why, but I felt it as a kid, just the way it was on repeat all the time. And we would sing it, and there was something about the album Spirit, the fact that he was still writing such beautiful music and willing to be so incredibly simple.

I mean, I compare Willie sometimes to Matisse. It’s some ancient parable, where some king wants the perfect drawing of a lotus flower, and he hires this great artist, and this great artist, and they all don’t lack the life. He goes to some ancient master and says, “Would you paint it?,” and in three seconds he does the perfect drawing of a lotus flower. It blows the king away, and he says, “But it only took you three seconds.” And he says, “No, it took me a lifetime.”

John Spong: That’s fantastic.

Ethan Hawke: That’s the way I feel about that whole album, Spirit. It takes a lifetime to be that simple. You know, “We don’t run, we don’t compromise.” “Too Sick to Pray.” There’s a couple great ones on that one. “I’m Not Trying to Forget You Anymore.” I don’t have the album in front of me. Almost every song on it is absolutely phenomenal in its utter simplicity.

And “Too Sick to Pray,” for me, it captures that strange feeling when you turn your back on your spiritual life, whatever you call that—your inner life, your quest for the divine, whatever name you give that that feels good. We all don’t know where we were before we were born, and we all don’t know where we go after we die. We don’t know why we’re on a star in space. Every now and then, we remember that we don’t know any of that, and you have this kind of longing for a connection with the divine. It captures that feeling of “I’ve been too sick to pray.” Like, I was too caught up in my own nonsense to even remember my humility. And there’s an unbelievable line in there where he says, “Remember the family, Lord. I know they remember you. In all of their prayers, they talk to you, just like I do.” I’m paraphrasing.

John Spong: Yeah.

Ethan Hawke: But what’s so incredible about that sentiment is, most songs about reaching out, and that are in pain, to me, they can be navel-gazing. You know, “I’m hurting. I’ve got problems with alcohol. I’ve got problems with drugs. I got problems with heartbreak. I’m not getting what I want. I’ve got illness.” And there’s something in the toss-away line about remembering the family, is that everybody we love is going through the same exact thing—all of the time. All the time, they’re too sick to pray, just like I am. And there’s so much, you know, “forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us.” There’s so much of the best . . . The warmth that can come from Christianity at its best is present in that song for me. It made my heart feel so good, when I was about twenty-six, twenty-seven, coming across this album, and Willie came back into my life, like he had when I was six or seven. Only now I was getting ready to be a parent.

[Willie Nelson singing “Too Sick to Pray”]

Ethan Hawke: If you are in love with the arts, the terrain around you is littered with so many people who lose their way. They have a little success, but they don’t know how to do it right. I’m not judging about any of that. But it’s just, it’s a hard path to stay on, of being in service of the arts. And the fact that Willie has been able to do it so consistently for so long was so inspiring to me, because Dead Poets Society came out when I was eighteen. I was just terrified that that was going to be my high-water mark in my life.

John Spong: Oh, wow.

Ethan Hawke: You know, it’s a strange thing to be a part of a band or a group of people that really contributes artistically. Peter Weir was amazing. For people who love cinema, Peter Weir is a legend. He made Truman Show and Witness and Gallipoli and The Year of Living Dangerously—so many great films. When I worked with him, he was truly a master. And then, also on set you had a comic genius. Overused word, “genius,” but in Robin Williams’s case, his brain does not work like other people’s. And I got to watch his creativity intersect with Peter Weir, John Seale, this brilliant cinematographer we had, who was also a staggering artist—and I got to do it with a group of young people. And so I got to share it. It wasn’t me alone. The other guys playing the poets, we had this amazing experience. And so I had this feeling, like, “Well, s—, it’s not going to get any better than this. Right?” I had to ask myself, “Well, what is the yardstick for success?” And pretty quickly you realize, “Well, it really can’t be what the outside world thinks, or else I will be rendered into this being my high-water mark. I have to see it as not “What is the arts going to do for me?” but “How can I help it?”

And Willie is an example of somebody who is in service of music. He’s in service of ideas. There’s that book, The [Tao] of Willie. He’s so clearly a part . . . He’s cultivated an attitude and an awareness of being a part of the Dao, whatever that means to you. He’s moving with the river of life. And because of that, at every age, he’s interesting, because he’s not trying to stay thirty-three. He’s not trying to stay forty-seven. He’s clearly an old man now. He’s not pretending he’s not an old man. And by the time Spirit came out, just even with the cover art on it, that beautiful photography of his—he looked like an old wizard, didn’t he? He looked like freakin’ Gandalf. Right? It just was really awe-inspiring to me that he could maintain this level of writing and musicianship. You know, his guitar playing might have been peak around Spirit.

John Spong: Yeah, it’s an amazing guitar record.

Ethan Hawke: It’s some kind of high-water mark. Why I admire it so much is like, yes, there’s the high-water mark of Jimi Hendrix and other sensational artists, but Willie’s is an act of simplicity. It’s these clear lines. Even his latest song, “Energy Follows Thought,” that could have been on Spirit. That’s the same songwriter. That’s the same songwriter who wrote “Always Now,” one of my other all-time favorite songs. That’s the same guy who wrote “Crazy.” It’s the same voice. “Hello Walls.” It’s the same . . . whatever that fire is in his chest, it’s the same one.

John Spong: One of the things that kills me about “Too Sick to Pray”—a slightly different read, but it’s like, Willie is such a devout person. What he believes is his own. It’s not standard, or orthodox, or whatever it might be. But he grew up in a Methodist church and went to that, and that stuff matters to him. Prayer matters to him. And the idea that he might be too down, or in too much pain to reach out, in a given moment, is really powerful. It’s such a different . . . it’s such a unique spin on the way people talk about Christianity a lot of the time. It’s like the great line in John Prine’s “Sam Stone,” where he says, “There’s a hole in Daddy’s arm where all the money goes / And Jesus Christ died for nothing, I suppose.”

Ethan Hawke: “I suppose.” Yeah.

John Spong: That’s a ten-year-old kid—supposedly, presumably—uttering that. How devastating. How heartbreaking that a ten-year-old just threw away everything that they ever believed. Similarly, for Willie to be too down and in too much pain, too sick . . . to reach out means that he was in a rough spot. But now he’s on the other side, and he’s checking back in.

Ethan Hawke: You’re saying a very similar thing, really, to what I was saying. It’s a different look at it, but . . . if somebody we admire as much as Willie is feeling that, it means you can forgive yourself, too.

John Spong: Yeah.

Ethan Hawke: But anyway, Willie embodies this thing in America, which is, he truly is a Christian, and that is very important to him—“Family Bible,” those hymns. But he also is an extremely learned man who’s traveled the world. He’s managed to take what he’s learned from the Dao or Buddhist traditions and see them alive and awake in Christian teachings, alive in what Jesus means to him. You feel that. I mean, “It’s Always Now” is a profound sentiment when thought about, as a Christian, when taking the mass—this beautiful idea that your grandfather didn’t live a hundred years ago; he lived in the present moment, just like you do. And we’re all a part of this cosmic “now.” I’d never heard anybody write a country song about that. I mean, that’s incredible! Right? It’s a miracle. He manages to get us all not afraid to think about volatile ideas, like a higher power and philosophical belief.

John Spong: Let’s—

Ethan Hawke: Should we spin the song?

John Spong: Yeah. Let’s listen to “Too Sick to Pray” together.

[Willie Nelson singing “Too Sick to Pray”]

Ethan Hawke: I love that song so much. Listening to it again, new, it does it to me every time. Even the line “I reckon that’s all, Lord”—it reminds me [of] something my grandmother said to me, is that even when you’re hurting and you don’t want to pray, just taking a second to try. It doesn’t have to be long. You really just have to check in, and then it becomes a habit.

And there’s something so funny about the line “I reckon that’s all.” You know I did . . . Willie was . . . I don’t know, it was some benefit, I think, for Austin musicians, and my daughter and I sang this song. If you could just see a little eight-year-old go, “Well, I reckon that’s all, Lord. That’s all I can think of to say.” At our best, we’re all basically eight. We don’t have that many profound things. And Willie does this so well over and over again, which is he finds one beautiful sentiment and writes a song around it—you know, “Hello Walls,” “Crazy,” whatever. It’s almost all a song or a great poem can really handle is just one truth. I mean, obviously, there’s other great songs, and you know, “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” does not apply to this idea. But what he does is one line, and he’s not pretentious about it. “I reckon that’s all, Lord.” There’s not much else I can think of to say, except I’m so sorry I don’t reach out more. I really do need you, and I’ll talk to you as soon as I can.

John Spong: There’s an implication of familiarity and closeness. It’s not talking to a deity; it’s a relationship.

Ethan Hawke: I guess that’s what it is, because I remember when I was . . . I was confirmed in the Episcopal Church. We had a female priest, and this woman, her name was Reverend Jean Smith, and she confirmed me. She gave this talk once that’s always stayed with me, which is, what if you imagine the divine as your best friend. Like, stop thinking of him as your father, or your mother, or your principal. The idea of “God as man” is that God actually understands what it’s like to be you. He actually understands all those dumb thoughts that you’re embarrassed by. You don’t have to be ashamed. You have a witness, and you have a friend. What if you talk to them like somebody who actually loved you and adored you, and that you adored? And if you could cultivate that relationship, then in times of real trouble, you’ll have a friend, and you’ll be a good friend.

Without being as pretentious as I just was, there’s something about that song that just does that. That’s where I’m talking about the simplicity of the old master who can paint a lotus. “I reckon that’s all” means “I don’t have to put on airs with you.” You know? “I’ve been sick. You know I’ve been sick. I hope we’ll be talking again if I’m not sick again, darn it.”

John Spong: Yeah. Yeah.

Ethan Hawke: I don’t know. I felt so moved recently by the last release that Willie did, because that same artist is at work in the newest record. I know we’re not going to have him forever, and I feel we’ve been blessed with album after album after album for the entirety of my life.

You pick anybody—Joni Mitchell, Bob Dylan. Pick whoever you want. Lots of them have five or six years that aren’t that good. [Laughs] They go through dark periods where they’re finding their new voice. And I think because Willie has always had such, uh . . . he’s never gone through a lost period. I know he’s gone through hard periods in his personal life, but his artistic life has seemingly always been there for him.

John Spong: That ties perfectly to this record, because this record, Spirit, comes out of some of those really hard personal times for him. It’s the late eighties, the hits had started to run out, and then he has the IRS problems in ’89, which stretches into ’93. He lost a son. Bobbie, his sister, lost two kids. That was in a year-and-a-half period. The label was talking about putting him out to heritage-artist category. And 1992 was the first year he didn’t release any music since 1957.

Ethan Hawke: Wow.

John Spong: Yeah, and that was it. Because of the IRS problems, he was a butt of late-night TV jokes, and they were making fun of him.

Ethan Hawke: Yeah, I remember all that.

John Spong: And he’s serious. He had not welched on his debt, and he made good on it later. But all of that was a really tough time. So now in ’93, he puts out Across the Borderline, which is such a great record. And it’s—

Ethan Hawke: Unbelievable record.

John Spong: —really hard to imagine that was a comeback record of sorts, but it was. But these songs on Spirit, which comes out three years later, are things that he wrote during that difficult period. That year when he didn’t write, or didn’t—

Ethan Hawke: Wow.

John Spong: —release, that’s “Too Sick to Pray.”

Ethan Hawke: ’Cause Across the Borderline is a brilliant record, but it’s mostly covers. It’s a lot of covers on that record, and they’re amazing. But this album—I didn’t know that, and that makes perfect sense.

John Spong: Yeah. This was the first album of nothing but new compositions—or nothing but his own compositions—since Phases and Stages in ’74. And so he’s always done that. There’s two great originals, new songs, on Across the Borderline. There’s “Still Is Still Moving to Me”—

Ethan Hawke: Oh yeah. God.

John Spong: —which is like you were saying just now about “Always Now.” “Still Is Still Moving to Me” sounds almost like a pat expression. It sounds so simple that there couldn’t be that much truth in it, but bullshit, there certainly is, just like “Always Now.” Yeah, it’s always now. That seems obvious and self-evident. Think about it for a sec.

Ethan Hawke: Yeah, think about it for a sec, and then all of a sudden you realize, “Oh, the entire universe is in that song.”

John Spong: Yeah. Yeah. That’s the other thing. He did Across the Borderline with Don Was, and then the two of them worked on a reggae album for a little bit. And so they go to Chris Blackwell in Jamaica, I guess at Ian Fleming’s old place, or whatever, where Blackwell lives—

Ethan Hawke: Yeah, GoldenEye. Yeah.

John Spong: Yeah. They go there to see if he’s interested, if Island will put out this reggae record, and Willie just happened to have Spirit with him. He had just recorded that with Bobbie. Mickey is not on Spirit. It’s just Willie sitting around in Luck, and he brings everybody in for this quiet, meditative thing that he’s working on to work through all this s—. He takes that with him, and Chris Blackwell hears that and says, “Whatever we want to do with the reggae album, we can. We are releasing Spirit as soon as is possible.”

Ethan Hawke: Wow. I didn’t know that story.

John Spong: And that’s how it comes out in ’96, and that’s how then it gets to you when you’re nesting. And what a great album to have playing, to have all of these thoughts and beliefs and ideas swimming through the house while you’re getting ready to change your identity.

Ethan Hawke: Yeah.

[Willie Nelson singing “Too Sick to Pray”]

Ethan Hawke: I have a question for you. Do you remember when . . . it was part of this whole Willie revival period around Across the Borderline. Do you remember when Johnny Cash and Willie did the VH1 Storytellers sessions? Would that be ’98?

John Spong: Ninety-eight. Ninety-eight.

Ethan Hawke: Ninety-eight. Okay, good. ’Cause this is right around the same time period where I was falling back in love with Willie Nelson, Across the Borderline, Spirit. Then I think we all kind of intuited that Johnny was getting near the end, and they did that VH1 special. And they were so magical together. And I remember seeing in the liner notes of it, Johnny Cash writes this thing that is so sweet and humble and moving, which is that he basically admits that he couldn’t play the guitar anymore when they did that—

John Spong: Oh, wow.

Ethan Hawke: —and that he really faked playing the guitar the whole session. He just kind of moved his hands—because his hands were bothering him so much. But then that’s when he realized how good a guitar player Willie Nelson was, that it sounds like there are two people playing the guitar, because Willie just did both their parts.

John Spong: Oh my God.

Ethan Hawke: You know, Willie would do a little rhythm, play a lead, do a little rhythm, play a lead . . . It makes me realize that this window, this moment in his life . . . when you survive that level of a low—meaning family, personal problems, money problems, public embarrassment, public shaming—I now see that’s probably why I came back into contact with him, because it was when the world came back in contact with him, really.

I remember . . . This is all during the same period when Maya, my oldest, was first born. Maya’s grandmother runs the Tibet House, and she’s very serious in her Buddhism. And she was shouting at the TV. We were watching it. She’s like, “Look at his earlobes! Look at his earlobes!” Because she was talking about how all the great lamas have these really long earlobes, and it’s the mark of an enlightened soul. She was like, “He’s enlightened!” I’m like, “I’ve been trying to tell you.”

John Spong: [Laughs] That was watching the VH1 thing?

Ethan Hawke: Yeah. I had this little baby in my arms, making everybody watch this speech, because I was blown away by it.

John Spong: I was going to ask how you went about introducing your kids to Willie. If your dad brings Willie to you, how do you bring it to your kids? And that’s one way. “Check out them earlobes.”

[Willie Nelson and Johnny Cash singing “Family Bible”]

John Spong: So, when you’re a kid, and your dad is playing Willie for you, what Willie . . . ’cause that’s the thing—Spirit is an adult’s album. If you had been ten when you discovered Spirit, it might not have worked on you.

Ethan Hawke: Yeah. Might not have worked on me.

John Spong: What Willie did you love then? Talk about the evolution of your life and your relationship with the music.

Ethan Hawke: Well, if I was going to be really honest, my connection . . . My mom moved to the East Coast, and we lived all over—Brooklyn, Vermont, Connecticut, Atlanta—and I really missed my dad growing up. He knows this. It was hard. He was really young when . . . He was nineteen when I was born, and we missed each other. My parents split up, and I was with my mom. I would come to Texas to visit him all the time, but I really missed him. And Willie just came to represent my father to me, I think. And so I listened to him all the time. As I was twelve and thirteen and fourteen, I would buy those greatest-hits records. You know, “The last thing I needed / The first thing this morning . . .”

John Spong: Man, I love that song.

Ethan Hawke: I had Willie and Family Live, you know, that big double album. I played the hell out of that record. And in the East Coast, when you’re a teenager, Willie was distinctly uncool.

John Spong: Really?

Ethan Hawke: Well, when I was graduating high school, it was 1988, New Jersey. I was just the only person who paid attention to Willie Nelson. They were like so . . . you know, Guns N’ Roses was the closest to country music they could be into. But I never stopped loving it. And I think that, strangely, as I started paying more attention to music . . . I think the album [that] came right after Red Headed Stranger, but I wasn’t aware of it until fourteen or fifteen, was Stardust. That’s the album that lets you know, okay, there’s a serious musician at work here. And also, don’t forget, I’m an actor. And I’m seeing him in Electric Horseman . . .

John Spong: Oh right, and Honeysuckle Rose, and Songwriter, and all those made-for-TV movies . . .

Ethan Hawke: I loved seeing artists operating outside their lane, and doing it well. We could even flip the channel and talk about his activism, and what he’s done for society and culture and elevating thought. As a young person, he kind of showed you a positive version of what an artistic life could be.

John Spong: I was going to ask, because I’m curious about the line between art and life. One thing that I’ve seen you say in places is that it’s hard as an actor, especially like when you’re doing stage stuff, because if you’re playing an unhappy person or an unkind person, you’re in that head for the duration of the production. I think you likened it to reading The Bell Jar every day for a month and a half.

Ethan Hawke: Yeah.

John Spong: It’s different for a musician, though, I guess, because Willie’s life seems to be his art. When he comes in off the road, he wants to go in the studio and pick with Bobbie and Jody and Johnny Gimble, which is how this record gets made.

Ethan Hawke: Well, you know, it’s funny that you say that, because through some connections I have in country music and different things, I’ve been invited to several Willie Nelson concerts. And in one of them, they didn’t have any seats, and they let me sit backstage, and I watched him go from his dressing room to the green room to behind the curtain to in front of the curtain, and it was exactly the same person. Meaning, I’ve spent my life backstage, and most people aren’t the same person. They’re not. And I don’t blame them. I’m not. It’s very difficult, when you feel two thousand, five thousand, ten thousand eyeballs on you, to change the stance of your shoulders, to cop an attitude in your voice, to present yourself in a way in which you want to be seen.

The person I saw backstage, talking to his friends, and having a glass of water, and doing whatever he did, stretching, was exact—there was no vibrational energy change in his bloodstream when he walked in front of thirty thousand people. That was his life. It was completely integrated, from my limited experience. I’m not friends with the man. Forgive me, Willie, if you’re listening to this. I don’t know you. I know you as an artist studying an artist. It’s what it seemed like to me. And it was really inspiring to me.

Ethan Hawke: And if you’re playing Macbeth eight times a week . . . The play is three hours long, first of all. It’s like a meditation on greed, power, anger, lust, and hatred, and it’s an incantation. You know they say, if you’re in a bad mood, “Hey, just breathe deep and smile, and if you do that for thirty seconds, it’s amazing”? It’s true. You do feel better if you do that. It’s stupid, but it works. Well, the inverse is true. If you put on an angry, hateful, murderous, lusting face for three hours a day, try making cereal for your kids in the morning. It’s—

John Spong: The kids better not complain.

Ethan Hawke: They better like those Rice Krispies, or they’re going to get that damn box up their nose.

John Spong: I’ll give you something to cry about.

Ethan Hawke: Yeah, exactly. My point is that what I’ve learned as an actor is what I first noticed with Willie, is how it seems to flow through him. It doesn’t get stuck in there. And I think the way you get to be Willie’s age, writing at the level that he is, is to let it flow through you. And you just see that. Good times, bad times, in-between times, boring times, exciting times, they’re all just moving. Still is still moving, right?

[Willie Nelson singing “Still Is Still Moving”]

John Spong: Yeah. If you made a Willie biopic, what’s it look like?

Ethan Hawke: Well, it’s funny that you say that. It’s hard for me to answer that, because I made a biopic about Blaze Foley, and I tried to make the whole movie look like what I remember about driving to the Willie Nelson Picnic in 1976. There’s a Navajo rug in the trunk. There’s a six-pack of Lone Stars in the back. There’s women with long hair laughing and dancing; and guys having fun, smoking cigarettes; and standing ashtrays. The look of that movie, I tried to conjure. And that’s—if I was doing a Willie biopic . . . You know what I would love? If I was doing a Willie biopic, the change would be—I think what he’s achieved as an old man is the high-water mark. And I wouldn’t set it in the seventies. I would set Willie’s biopic now, because we don’t have a lot of examples showing us how to age well.

This country, the world, puts a tremendous amount of energy into teaching young people how to go to college, fall in love, have a baby, and get a job. Have a career path. And then they’re done with you. But, you know, most of us are like thirty-five, forty when that happens, and we’ve got a long life to go. And we don’t have a lot of mentorship to show us how to get from forty to eighty, and be a meaningful, substantive human being. And how to let go of youth gracefully, you know. How to absorb what is positive about where we are right this second. We don’t have a lot of that. And, you know, the Nelson Mandelas of the world are few and far between, and we need them.

John Spong: Yeah, desperately. So I wonder, then, what would be the takeaway from that movie? What’s the great lesson of Willie’s life?

Ethan Hawke: Authenticity. He is authentically himself. You don’t have to like him, or you don’t have to care, or you don’t have to . . . But I think for all of us, the trick is to be the best version of who we are, not the idea of who we want to be or who we wish we were. Each one of us has a tremendous amount to offer the world with our life, the simple gift of our life. And when we make it smaller than it is, we hurt everybody.

And I think that Willie has just been so . . . you know, the big breakthrough with Red Headed Stranger is when he started playing like himself—how he always wanted to play. I think we all can do the same, in whatever. Yes, his is iconic, and he plays a large role in a lot of people’s minds, and not all of us are destined for that, but we can be ourselves. And that is a great service in whatever way you can do that. And I think that that whole Spirit album, and particularly “Too Sick to Pray,” is a great example of somebody relaxing into themselves and trusting who they are is enough. I reckon that’s all.

[Willie Nelson singing “Too Sick to Pray”]

John Spong (voice-over): All right, Willie fans. That was Ethan Hawke, talking about “Too Sick to Pray.” A huge thanks to him for coming on the show, a big thanks also to our sponsor, White Claw Hard Seltzer, and a big thanks to you for tuning in. If you dig the show, please subscribe, maybe tell a couple friends, or visit our page at Apple Podcasts and give us some stars. Please also check out our One By Willie playlist at Apple Music. Oh, and be sure to tune back in next week when we close out season three of One by Willie with his longtime record producer and cowriter, Buddy Cannon, who will talk about one of the most powerful songs they have written together and that Willie has ever recorded, “Something You Get Through.” . . . We will see y’all next week.