Subscribe

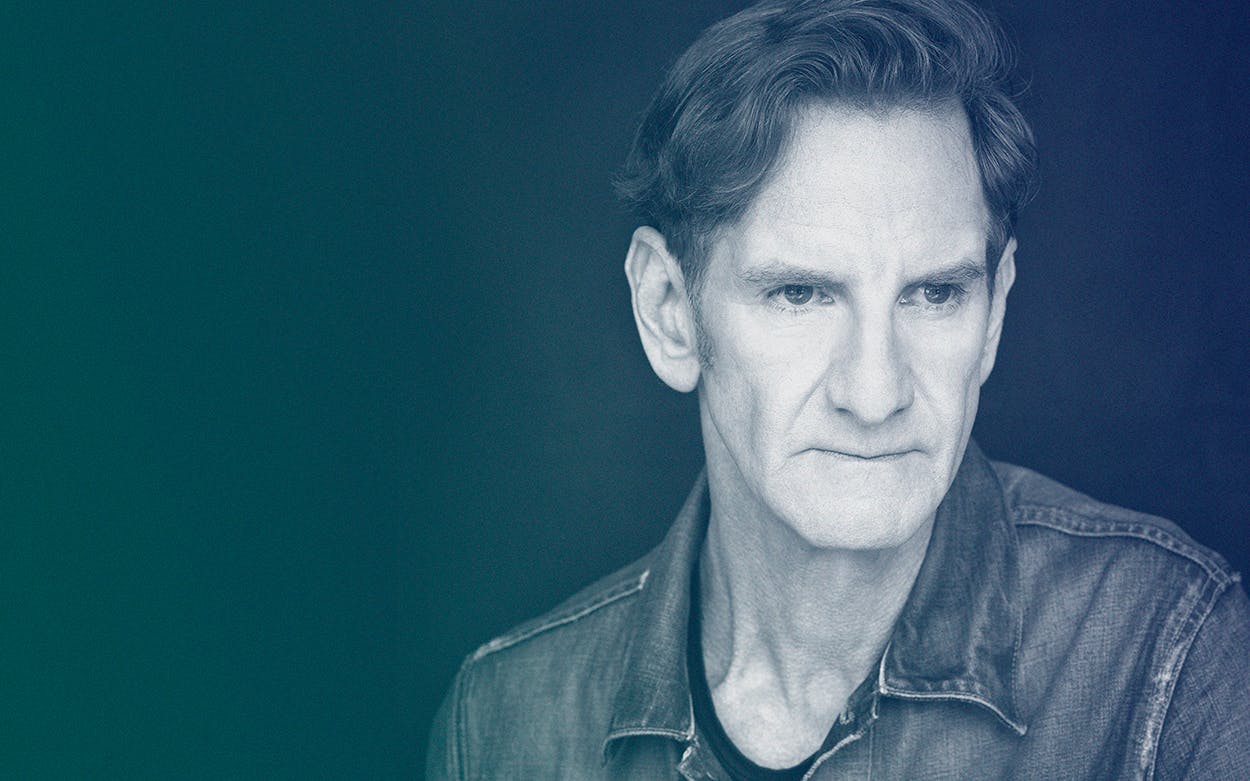

Last Wednesday evening, photographer Mark Seliger was honored by the Texas Cultural Trust at its biennial Texas Medal of Arts Awards ceremony as part of a 2019 class that included Matthew McConaughey, designer Brandon Maxwell, stage star Jennifer Holliday, music legend Boz Scaggs, and Texas Monthly’s own Stephen Harrigan. While Seliger, the Amarillo-born, Houston-raised graduate of Houston’s High School for Performing & Visual Arts, has built his status in the photography world by focusing largely on portraiture of A-list actors, musicians, and politicians, he says the ceremony itself wasn’t a time to be thinking about the perfect shot of somebody like McConaughey or Holliday.

“Over the years I’ve really been able to compartmentalize when I’m working and when I’m doing other things,” says Seliger, who shot more than 125 covers for Rolling Stone as its chief photographer from 1992 to 2002, then spent the next decade at Condé Nast, working primarily for Vanity Fair. “You have to, or you’ll destroy everybody in your sight and also destroy yourself.”

Just 72 hours before arriving in Texas for the Medal of Arts festivities, Seliger was very much focused on snagging the perfect shot. On Oscar night, at Vanity Fair’s Academy Awards after-party, Seliger photographed dozens of Hollywood’s biggest stars inside his portrait studio for a series almost instantly uploaded to Instagram. Its subjects included Lady Gaga, Spike Lee, Regina King, and Glenn Close. The images generally belie how quickly they were shot. Since there’s not a lot of time to establish trust between photographer and subject, the Oscars party is an annual exercise in both planning and instinct that Seliger says is unlike any other shoot all year.

“I’ve really learned how to work a certain muscle, an intuitive muscle,” says Seliger, whose work has been installed in the permanent collection of the Houston Fine Art Museum, the National Portrait Gallery in London, and the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. “I do quite a bit of research on who’s going to be there before we go in. Still, you have no idea. You’re going to have a ton of surprises. So the key is to be nimble and light on your feet. I think there’s also a certain amount of charm that you spray on before you walk into the room, so that you’re communicating with these people and directing these people as quickly and as communicatively as you can.”

On this week’s National Podcast of Texas, Seliger offers his thoughts on how Texas influences his approach to portraiture and how photography can still thrive in an age of digital photography and mobile devices. Plus, he walks us through his memories of classic sessions with Kurt Cobain, Jerry Seinfeld, Lyle Lovett, and Donald Trump.

Some highlights (condensed and edited for clarity):

On the first time he worked with Lyle Lovett

I think there is that element when you meet your heroes that no matter how the rest of the world feels about them, it can be very intimidating. When I met Lyle, he was very reserved—nice and polite, as we all know Lyle is. But once we started talking, the walls came down. We had a great time. We had commonalities to talk about, and we just kept on coming back to each other. And he actually wrote a beautiful essay for my last book. That intimidation is tough at first, but you find that communication, that way to relate to each other. As he says, there’s nothing more uncomfortable than sitting in front of a camera and not knowing what’s gonna come out of it. Are you going to like it? As the subject, you’re just praying it looks like you.

On three sessions with Donald Trump

It was Atlantic City. It was very fast. He had two expressions, which he told me he had. He said, “I can give you the mean look, or I can give you the smile.” And so I think I went for the mean look. And surprisingly enough, Jann put him on the Rolling Stone cover right before he was nominated for the Republican ticket. And I have no idea why he did that. But he did it anyway. And he was the same guy. He was completely playing the part. He told me again that he had two expressions. We tried both of them; the angry won again. And the next time I shot him was a couple of weeks later. They asked me to do a book cover. And he walked in, and he said, “What are we doing today?” And the Simon and Schuster editor was there, and he says, “Well, we’re shooting your book cover.” And he asks, “Is it good?” And they said, “It’s just a collection of your speeches. We’re just taking that and putting it into a book.” And he asks, “But do I need to read it?” And they told him they didn’t have time because they needed to get the book out the door today. And he said, “Let’s do this.” He was prepared with both expressions.

On living in a digital world

A modern experience with images has to translate electronically because the next generation that’s going to be looking at images, they’re going to look at things not even on their iPad, but on their phone. And so photography is a tool. It’s a paintbrush, and the canvas is whatever people are receiving that information on. And so you have to really embrace the fact that not only is it going to be a changing format—and a much smaller format in some cases—but it also is not just a still image. It’s a moving image. I thought about seeing [photographer] Robert Frank and those incredible images of [his influential 1958 photographic book] The Americans and then seeing him make films. That’s a natural transition for a lot of artists. It’s just a different way of painting the picture. So I don’t think you’d be afraid of anything. You always have to hold on to the value of a printed piece that you can put on the wall, never underestimating the power of a print, but also being open to the idea that an image can have an effect on however it’s viewed, whether it be a beautiful coffee table book or a phone.

On the shot that wound up on Rolling Stone’s 1994 Kurt Cobain memorial issue

There was some luck that day. We got Kurt at a very, very good time. He was seemingly in a great mood, very clean and clear. We did that same portrait set-up for every member of the band. But I did a Polaroid, and since he knew I was doing a Polaroid, and that’s a test, there was something about that Polaroid that I didn’t get in the 10 shots on film that followed. And I think, because in his mind it was just a test. you can really see in his eyes the sense of what I would consider to be almost melancholy and sadness. And the rest of the shoot was very joyful. But at that moment there was a real connection, an internal thing that was happening with him. And after the shoot, I knew that that was the picture. I had a Polaroid negative because this particular process is called 55 Polaroid. So you get a negative off of the Polaroid, and you have to stick it in a bucket with water until it washes. And then you dry it. I was on a plane going back from Michigan back to New York, because I had a job the next day. So here I was, walking through security with Kurt Cobain in my bucket. And what I loved about that image is that’s it’s almost like an Edward Curtis picture of a Native American. It was that kind of soulful, formalistic approach to portraiture that I’ve always been attracted to. And then two months later we were in Paris, shooting the Counting Crows for a cover of Rolling Stone, and my editor called me up, and she said, ‘We need your picture. Kurt Cobain just shot himself.’ We lost an incredible artist and someone I’d really come to admire.

On growing up in Texas

Texas is where I got my first break. This is where, in a little classroom at the Jewish Community Center in Houston, I took my first photo class. And then I set up a dark room at my parents’ home because I was too shy to go out and bop around with the neighbors’ kids. So I just would print on a Saturday night when my parents are out of town. Then I went to East Texas State. Commerce was not a pretty place to hang out in, but it gave me a sense of commitment. And then once I got those tools, I had appreciation of everything I saw. So I have a real fondness for what I learned here. And then there’s the poetry of the landscape that’s undeniable. I grew up in Amarillo for a short time, and I still have memories of my dad taking me out to Borger and the canyons and seeing sunsets, buffalo, and horny toads. These were pretty remarkable formative experiences.