Listen to this episode on Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher | Google. Read the transcript below.

Subscribe

The last public speech [Quanah Parker] gave was at the Texas State Fair. And he told audiences, “I challenge you to go forth and tell Texas history straight up.”

—Dustin Tahmahkera

To understand how the Texas Rangers’ legend took hold, we explore three stories about their early conflicts with Native and Mexican American people. First, we follow the footsteps of Ranger captain Jack Coffee Hays, up Enchanted Rock to the site of his famous shootout with Comanche warriors. Then, the Comanche scholar Dustin Tahmahkera explains the abduction story of Cynthia Ann Parker and the life of her son Quanah Parker. Finally, we visit the Guadalupe Mountains, near El Paso, to hear about the Rangers’ surrender during the San Elizario Salt War.

White Hats is produced and edited by Patrick Michels and produced and engineered by Brian Standefer, who also wrote the music. Additional production is by Isabella Van Trease and Claire McInerny. Additional editing is by Rafe Bartholomew. Our reporting team includes Mike Hall, Cat Cardenas, and Christian Wallace. Will Bostwick is our fact-checker. Artwork is by Emily Kimbro and Victoria Millner.

This episode features additional field recording by Daniel Beck and Ivan Pierre Aguirre.

Archival tape in this episode is from KMOL-TV and the University of Texas at San Antonio Libraries, and the Texas Archive of the Moving Image, courtesy of the Texas Historical Commission.

Transcript

If you drive northwest from Austin, across the green hills and running creeks of the Hill Country, after about an hour or two, you’ll see a huge pink dome rise out of the landscape.

It’s an enormous granite formation, smoothed out by millions of years of wind and rain. And, for maybe as long as people have lived on this land—and certainly from the times of the earliest Kiowa, Tonkawa, Apache, and Comanche—there have been ghost stories about this place.

One story tells of a Native man who went to the rock to sacrifice his daughter to the gods. But instead, the gods condemned him to walk the surface of the rock for eternity. The Tonkawa claimed to see “ghostly fires” burning at the top of the dome at night. And they and the Comanche both told stories about fallen warriors haunting the rock, hiding in its dark caves and fissures.

Late in the day, as the sun sinks beneath the horizon, the rock has been known to groan and sigh. From deep in the earth, eerie sounds emerge. A geologist would tell you it’s the sound of granite contracting as it cools. Others will say it’s the sound of phantoms, of Native people from these hills. Today, Texans call the formation Enchanted Rock.

[Truck door slams]

I went out there last summer—not to hunt ghosts, but to look into one of the famous legends in the history of the Texas Rangers. Because it was here, at the apex of Enchanted Rock, that the iconic Ranger captain Jack Coffee Hays supposedly held off as many as one hundred Comanche warriors, entirely by himself, with only a rifle and two pistols.

It’s a classic bit of Ranger mythology: a lone ranger, in a wild land, facing down death with good humor and poise.

But this story also gets to the how and why the Rangers came to exist in the first place. This year, talking with Mexicans and Tejanos across Texas, I’ve heard tales of La Matanza: a time when Rangers killed hundreds of Mexicans and Mexican Americans, just a little over a century ago. It’s easy to condemn racist violence. But I wanted to understand how this could happen. What in Ranger history created the belief that protecting some Texans meant attacking others?

To understand what it meant to be a Ranger, back in those first one hundred years, you have to understand their relationship with Native Texans. In the early years of Texas, the state was consumed with chaotic violence and warfare from all sides, as Anglo settlers fought the Natives and Mexicans who were already here. In this episode: three Ranger legends that come out of those wild days—stories that mean very different things depending on whose history you claim as your own.

Out on Enchanted Rock, I didn’t hear any eerie sounds or spot anything ghostly. But, tracking down the Rangers’ early days, I found myself haunted by some of the most restless spirits in Texas history.

From Texas Monthly, you’re listening to White Hats: a story of the Texas Rangers and a battle for the soul of Texas. I’m Jack Herrera. This is episode two: “Ghosts of the Wild West.”

[theme music plays]

You might remember Jack Hays from the last episode. His battle with the Comanche at Enchanted Rock is the story that helped launch his career in politics and cemented his legend. But the director of the Ranger museum told us that he had his doubts about the facts of the story, even though the painting of Hays on Enchanted Rock was one of the museum’s most prized possessions.

A lot of tall tales about the Rangers have a way of getting taller with time. The story goes that Hays had found the perfect cover: a crater at the very top of Enchanted Rock, where he could shoot out at all sides. I wanted to go to find that same crater, to sit where Hays may have sat all those years ago.

So we climbed the rock in search of Jack Hays: me, two producers, and another writer at Texas Monthly, Christian Wallace.

Christian Wallace: I guess I’m coming in from, like, the Fredericksburg side . . .

Christian knew this story too—he’d read about it in college. And he’d grown up on stories of the Rangers and their exploits.

Christian Wallace: Yeah, I mean, it’s, like, such a bedrock of your worldview, if you grew up here. And those foundational myths shape how you view yourself and the place you live. I think part of that is, I think I wanted so badly for it to be true in certain ways. Like, I wanted to have heroes that were noble and good and that I could believe in.

I was grateful Christian agreed to come with me to Enchanted Rock. Besides being a good sport about these kinds of things, Christian is one of the most thoughtful journalists writing about Texas today. He’s from out in West Texas, where his family’s got deep roots. A couple years ago, he hosted Texas Monthly’s podcast Boomtown, which tells the story of the oil country he grew up in. He thinks a lot about the foundational legends in Texas history, and what they can tell us about the state today.

When it comes to the story of the famous Jack Hays shootout, Christian and I had trouble believing it could be true. But we decided to keep an open mind. First step was understanding what, exactly, is going on in the story. And Christian had come prepared to help us out.

Patrick Michels: What’s the book?

Christian Wallace: Texas Ranger: Jack Hays in the Frontier Southwest, by James Kimmins Greer. It was first published in 1952.

Christian had an old copy from the San Marcos Public Library, with yellowing pages and an inside cover full of stamps from all the people who had checked it out over the years.

Christian Wallace: All right, this is actually important. So we’ll start here.

The story begins with what Hays was up to in 1841. Not just a Ranger, he was also a land surveyor—which might sound like boring work, but was actually pretty dangerous back in those days. His job was to travel the Hill Country and map the terrain. His work helped Anglo colonists make claims to land that belonged to Comanche, Tonkawa, and other Native people. Hays would travel deep into hostile territory to take notes. That’s what he was doing at Enchanted Rock: along with another early Ranger named Henry McCulloch.

Christian Wallace: They’re camping, and it says, “As Hays placed one of his five-shooters—new and rare weapons—in its belt scabbard, McCulloch saw him pat it gently with his hand and heard him say in a low confiding tone, ‘I may not need you. But if I do, I will need you mighty bad.’ ”

As Christian read, we stared up at the same slope of granite Hays had scaled all those years ago to survey the land.

Christian Wallace: All right. Should we walk?

Jack Herrera: Yeah. Before it gets too hot, let’s head up that rock.

Christian Wallace: And we begin the ascent.

We emerged from a line of trees, and suddenly there was nothing in front of us but the rock. It was easy to imagine being back in time—so much so that as I tried to get into Hays’s mindset, my heart started pumping just a bit faster. What would it have been like sprinting for cover across that unforgiving granite, with warriors closing in on me, arrows whizzing past my head?

If you’re thinking that Jack Hays’s story sounds a lot like a western movie, you’ve got it backwards: western movies look and sound a lot like Jack Hays.

TV narrator: Almost every western hero who has ever stalked across the silver screen is only a distillation of this man, the original western lawman, John Coffee Hays.

That’s a 1970s sound bite from a TV station in San Antonio. Hays was an origin story for the entire myth of the Wild West. The brave white man with a pistol, settling a wild and violent country.

TV narrator: He was a captain of the Texas Rangers at age twenty-three, and for the next decade fought Mexicans, Indians, and outlaws with deadly enthusiasm.

Hays was born in Tennessee to a well-connected family. He was actually related to Andrew Jackson, the seventh president of the United States. From an early age, Hays sought out adventure. At just nineteen, he immigrated to Texas just as the republic won its independence from Mexico. Sam Houston, the first president of Texas, appointed Hays a member of the Texas Rangers.

At that time, the Rangers were fighting the most powerful military force in the west: the Comanche. From the land around what we call Wyoming today, the Comanche had swept down across the Great Plains and built an empire that stretched deep into modern-day Texas. Their warriors’ skill on horseback was legendary. They had outfought Spanish colonists, who retreated from the territory they called El Comanchería. No force could take them.

In many ways, that’s why the Rangers were formed. Their job was to protect white settlers from Comanche raids, but also to bring the battle to the Comanche, and push the white man’s frontier even further west.

As the legend goes, if not for his mettle and his luck, Hays would have met his end fighting the Comanche right here on Enchanted Rock.

Hays built his name fighting Comanche, but he was also known for building partnerships with other Native people. The Comanche had pushed the Lipan Apache off the plains and south into Texas. When Stephen F. Austin and the first Anglo settlers arrived, they created an alliance with the Lipan Apache to fight their shared enemy. Some Lipan Apache would actually be appointed as Texas Rangers.

Hays formed a partnership with the Lipan Apache chief Flacco, another famous warrior. Hays credited the chief with saving his life. During a battle, Hays’s horse spooked and charged him headlong into a group of Comanches. Flacco saw it happen, and rather than let Hays face the onslaught alone, Flacco joined him in a two-man charge. Amazingly, they survived. After the battle Flacco is said to have uttered a famous line, saying that Hays was “bravo too much.” The nickname, “bravo too much,” stuck with Hays for the rest of his life.

Hays became one the most important leaders in the Rangers’ campaign against the Comanche and ventured deep into the Comanchería, where Christian and I now stood.

Christian Wallace: Yeah, we’re actually, like, higher . . . like, birds are flying below us at this point.

Jack Herrera: Yeah, we’ve got a hawk—or is that a vulture?

Christian Wallace: I think that’s a turkey vulture. There’s a few more circling up ahead.

Jack Herrera: Should that make us nervous? [laughs]

From the top, we got a 360-degree view of the oak groves and chaparral down below. Here’s how Greer described it in his book:

Christian Wallace: “The summit appeared to be about twenty by twenty feet. Hays had climbed the sloping side, looked at its crater, studied distant landmarks, and then was descending the hillside toward camp when he saw a score of Indians advancing to intercept him.”

It was a party of Comanche warriors. There are countless tellings of what happened next, and different accounts record different numbers of Comanches coming after Hays.

Christian Wallace: Yeah. This is, um, very, like—there’s like a hundred warriors now, and . . .

Jack Herrera: It’s incredible how much the numbers just—I think, just jumping from source to source, like some, it’s like “a dozen men,” “eighty men,” now a hundred. A hundred’s the biggest number I’ve heard so far.

Christian Wallace: “There was three thousand men.” [laughs]

Jack Herrera: Yeah. “Two helicopters, and . . .” [laughs]

Here’s how the story goes: Hays scrambled back up the mountain and took cover in a crater at the top of the rock.

Christian Wallace: “When he reached the crater, he slid down into its shallow pit and hurried to the north side, where he secreted himself between two projecting ledges under an overhanging rock. That’s pretty specific.”

But at the summit, we quickly spotted one problem with Greer’s story: there’s no crater at the top of Enchanted Rock—at least not one that looked deep enough to provide cover.

Jack Herrera: Crater’s not the right word. Especially not the sort of bowl that’s described.

Patrick Michels: You could call that a crater if you were gonna take a few liberties, but . . .

Jack Herrera: Yeah, a depression of some kind.

As Greer tells the story, Hays did find one. But he was still in trouble.

Christian Wallace: “In assembling his weapons he discovered he had lost his powder horn. He could fire only eleven shots. Hardly was he settled in his position when he saw numerous Indian heads peering above the rim of the crater. From their whoops and their calls to him, it was obvious that he had been recognized. They shouted ‘devil yak’ and ‘silent white devil,’ and many worse names in Spanish, which they knew he understood.”

For hours, Hays remained pinned there, firing, waiting, firing, and waiting. Counting his chances of survival down from eleven. Somehow, Hays managed to hold them off. But then the Comanche charged.

Christian Wallace: “Most of the Indians leaped to the top of the crater and slid down into it. Hays killed one of them. He knocked over two more as they rose to their feet. As they rushed him, he dropped one, and then another, who fell head-foremost against his shins. At the moment he was about to spring forward with his Bowie knife, to do what damage he could against the others, a chorus of Texas yells routed his attackers. His men had heard his guns.”

Hays was saved. The Comanche fled.

Even back when Hays was still alive, I have to think that people at least suspected that the Enchanted Rock story was exaggerated. But that’s always been part of the charisma of these stories. When you set a tale in the West, in plateaus and deserts that few have traveled, fact and fiction can blend. The Wild West becomes whatever you want it to be.

Climbing down off the mountain, it felt like our search had been a little inconclusive. But whatever the historical merits of our expedition, it was fun. The safe return to flat ground might’ve been sweeter for Hays: he had survived, and taken his first steps into Texas legend. But—at least in Greer’s account—there wasn’t a snow-cone stand at the end.

Patrick Michels: How ’bout a classic piña colada, please.

Snow-cone seller: Piña colada?

Patrick Michels: Yeah.

Snow-cone seller: Here you go, sir.

Patrick Michels: Awesome, thanks so much.

Snow-cone seller: Have a great afternoon. Stay safe.

It was a beautiful day. We sat at a picnic table and took a minute to enjoy being there. The wind blew in the mesquite, and the creek beds under the oaks were cool and shaded.

As we sat, I had a sudden jolt of nostalgia. It was a little like that moment I’d had at the museum, when I’d played with the Colt Walker revolver. It all reminded me of the game I’d played as a kid with my twin brother: cowboys and Indians. I had the cap pistols and the cowboy boots—even a real bow and arrows. (Thanks, Mama.)

But I’m older now, and I understand that the story of the West isn’t the story of a fair fight between “cowboys” and the Native people who have lived here for thousands of years. Instead, it is a story of genocide.

When European settlers first arrived in the area around Enchanted Rock, Comanche and Tonkawa might have used the rock to hide: from the crags underneath the summit, groups of families could huddle together, invisible to people passing down below. On the summit of the rock this summer, chasing Hays’s story, I thought about these first peoples.

Today, thousands of Comanche people still live in Texas, and there are 17,000 enrolled members in the tribe. But the great empire their people once had on the plains is no more. In many ways, early Texas history is the story of how the Comanche were killed, removed, and forced out of the lands we call Texas.

I have to wonder how this history would read differently if the Comanche had won and then got to write their own textbooks. How would the Comanche describe themselves in this history?

Of course, that question was not abstract. The Comanche people still exist. And I could ask them.

Dustin Tahmahkera: So I’ll begin in the Nʉmʉ tekwapʉ̠, in the Comanche language. In greeting, I say, haa. . . . Nʉ nahnia tsa Dustin Tahmahkera. Tahmahkera.

This is Dustin Tahmahkera. He’s a professor at the University of Oklahoma.

Dustin told me how he was raised with two different ideas of the Comanche: the one he learned from his family, and the one he learned from the white people around him.

Dustin Tahmahkera: I was born in the Comanche Nation capital of Lawton, Oklahoma, and grew up mostly just south of the Pia Pasiwahunu, the Red River there in the Wichita Falls, Texas, area. More specifically, the small town of Iowa Park, Texas.

Like every other Texan kid, Dustin learned about the Texas Rangers, including their clashes with the first peoples in Texas.

Dustin Tahmahkera: So, I believe it was in sixth grade. And I was probably sitting in the back of the classroom, if I could get away with it. And we’re sitting there in history class one day, and it came about where it was that one day, or two days, out of the year where “Induns” would be talked about. And “Let’s cover Indun history in Texas in one day.” It was usually very concisely done, in maybe one, two paragraphs of wrapping up this huge, complicated history, and putting it into a nutshell of saying, “American Indians were an obstacle to the progress of building this country.”

As a Mexican American, I’ve seen textbooks and TV shows call us the bad guys. But I’ve never seen myself described as “an obstacle.” Dustin says it was eerie to read about his people in the past tense, as if they were extinct—as if the Comanche Nation’s capital wasn’t just an hour north of that classroom.

But Dustin knew what to expect in school on days like this.

Dustin Tahmahkera: And as soon as Comanches are mentioned, feeling my heart race, feeling the anxiety going up. Because you’re ready for it—even by that age and as a young teenager—ready for, here we go again. What’s going to be said? Is someone going to start clapping their hand to mouth? They did. That was still commonplace. It still happens. Someone putting fingers behind their head to signify feathers.

Not many of Dustin’s classmates knew that Dustin was Native. As a kid with both white and Comanche ancestors, Dustin could often pass as white. On days like this, he had to choose how to present himself. That’s a hard thing to navigate as a middle schooler.

Dustin Tahmahkera: I grew up as someone who was proud to be Texan and also proud to be Comanche, and didn’t ever want to feel like I had to choose either-or. I can still recall even filling out census records in my teen years, and being told that I could only pick one box. And that was part of what it felt like in the classroom that day.

Dustin remembers his classmates sharing vague rumors they’d heard, that they were actually part Comanche, or even descended from famous chiefs. Like an exotic family secret. But Dustin was a shy kid and didn’t always feel safe letting people know he was Native.

Dustin Tahmahkera: But the teacher wasn’t spotlighting me, you know, and I was appreciative of that—not calling me out. It was a time in which I chose to pass.

It was a strange moment, his classmates competing to claim an identity he knew was his own—but as a novelty, a relic of a Texas past that had been erased by “progress.”

Dustin Tahmahkera: I grew up being proud of both sides of the family, of the Anglo side and the Comanche side—being proud to be both. And even though others at times wanted me to choose, for me it was just an all-of-the-above kind of approach. And it’s a framework that I learned from the legacy of Quanah.

Quanah is Quanah Parker. You might have heard of him. He was the last great chief of the Quahada Comanche, among the last Comanche bands to challenge Anglo rule in Texas. In an alliance with other Native people, he resisted removal, fighting against the soldiers trying to force his people onto a reservation or an early grave.

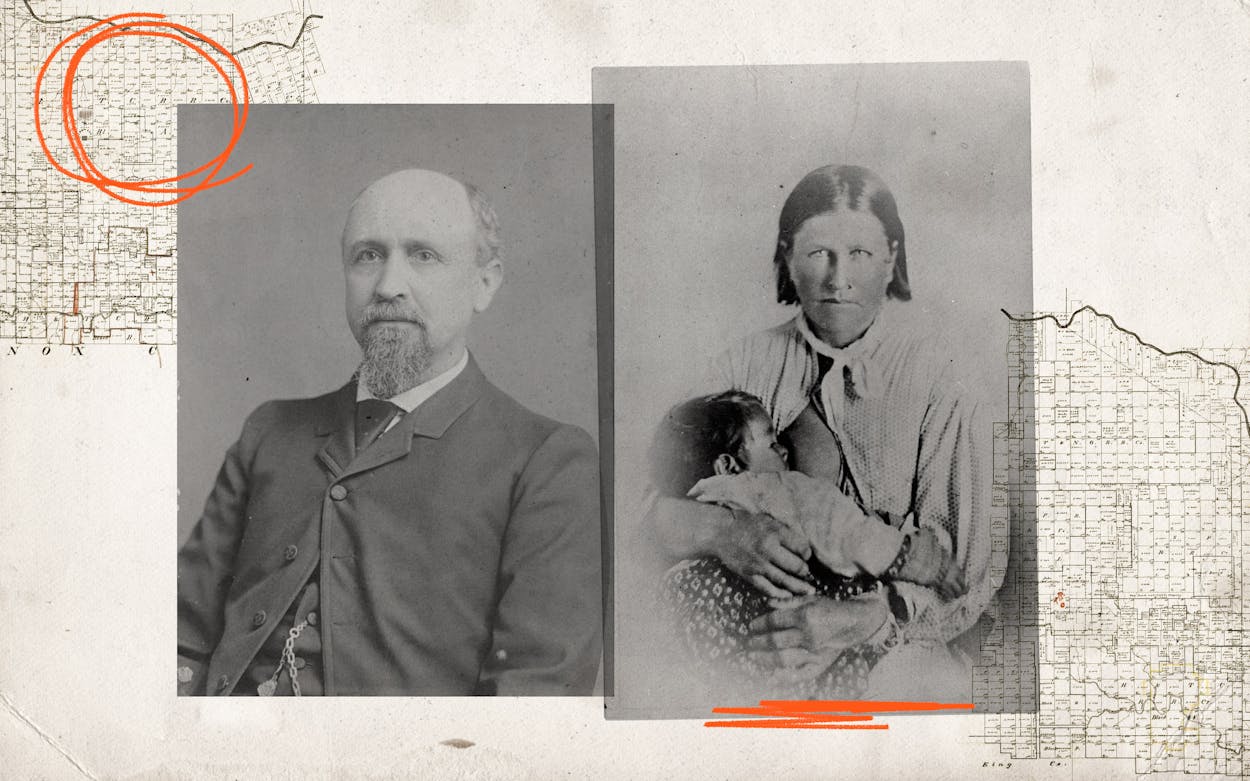

He was a legendary figure, and a household name in the U.S. In many ways, he is the origin of Hollywood’s archetype for a Native chief—a powerful warrior and a sage diplomat. A famous photo shows him wearing an enormous feather headdress and riding on horseback, armed with a lance. His legend persists to this day. That day in school Dustin told us about? Some of his classmates claimed that they were related to Quanah Parker.

Like Dustin, Quanah Parker had both Comanche and white heritage. And Parker’s remarkable story goes a long way to explaining what happened to the Comanche in Texas.

Before Hays and the Texans arrived, the Comanche were still relative newcomers.

Dustin Tahmahkera: Comanches are the tribe that, to this day, is arguably synonymous with Texas. That, in effect, marginalizes the Caddos, the Choctaws, Cherokee history, especially Lipan Apaches, Tonkawas, Coahuiltecans.

There were already Native people here when the Comanche arrived. Though their roots on this continent go back thousands of years, they were also an imperial force in Texas. They had dominated other Native bands, like the Tonkawa and Lipan Apache. That’s why so many tribes wanted to help European settlers fight the Comanche.

But even facing so many enemies, for a long time, the Comanche couldn’t be beat. European armies had traveled with long, slow supply trains and lined up for battle in formation. They were easy targets for the Comanche, who traveled fast and light on horseback. Eventually, the Texas Rangers found success by mimicking the Comanche’s own techniques: moving in small bands, roving on horseback.

But what finally gave the Rangers their edge was their famous gun. In the 1840s, the former Ranger Samuel Walker met with the renowned gunmaker Samuel Colt and asked him to invent a gun that Rangers could holster in their saddles and fire from horseback. The iconic Ranger six-shooter—the Colt Walker revolver—was born. The tide began to turn in the war between Texans and Comanche.

In newspaper stories from those days, white writers focused on Comanche raids and their brutal treatment of captives. The Comanche killed women and children in attacks and would often torture and mutilate captives. Those images stuck.

Dustin Tahmahkera: You know, there’s this long-standing, reductive story of Comanches as hypermasculine and hyperviolent male warriors that has played out over and over again, that in effect is really just reinforcing very dated old views by Walter Prescott Webb and T. R. Fehrenbach and others, who emphasized so much on the warfare. And that’s illustrative of how often stories that are about us are without us.

Of course it’s never that simple: who is “warlike” and who is “civilized.”

Dustin Tahmahkera: I think just about all of us come from societies where there has been peace and war, and trading, and taking, and looting, and so forth.

Because, to put it in Dustin’s words, the Comanche had been raiders and traders. Caretakers and captive-takers.

Dustin Tahmahkera: We don’t deny that taking captives is a huge part of how we built up this empire, this dominance on the Southern Plains. But I call for a much larger picture that is put into context of why captives were taken, and that sometimes, if Comanches lost children in warfare and in battle, that you took on other people’s children, to bring them into your family, and to build up that family unit again.

That’s not exactly how the press described the abduction of Anglo children in Texas. The Rangers rescued many captives in daring battles, and they’re actually at the heart of one of the most famous of these abduction stories. It helped solidify their place as heroes on the national stage.

The story begins with a family who moved from Illinois to try their luck in Central Texas, east of where Waco is today. That’s where they established a fort, Fort Parker.

Texas in Review narrator: In the spring of 1834, a little band of pioneers led by John Parker built this stronghold. It became the home of thirty-one people. The fort is an excellent example of how our forefathers met the threat of the Comanche and Kiowa Indian raids of that period.

Back then, this was still the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas, and Anglos were pretty much new here. The Parker family was part of this colonization effort, farming, ranching, and trying to make a life here.

Texas in Review narrator: Its blockhouse, its cabins, its walls tell better than words the faith our forefathers had in the future of the frontier.

It didn’t go well.

Texas in Review narrator: On May 19th, 1836, three hundred Comanche and Kiowa braves attacked the poorly defended structure. Moments later, most of the settlers lay dead. Though these Parkers died defending the fort, Texas history remembers best little nine-year-old Cynthia Ann Parker, who was captured by the Indians.

Dustin Tahmahkera: Numerous Parkers are killed. There’s horrific stories that have come from various Anglo accounts of what happened that day and in ensuing weeks. Cynthia, though, was taken captive, was raised Comanche.

Her name became Naduah, and she slowly lost much of her ability to speak English. Eventually, she married the chief of the band, a man named Peta Nocona, and they had three children. One of these kids was named Quanah—Quanah Parker.

When Quanah was still just a boy, his life and his mother’s life changed forever. On a cold day in December 1860, the band was camping along a creek near the windy plains of the Texas Panhandle. In the weeks before, some of the band had carried out raids on Anglo settlements.

Dustin Tahmahkera: Part of the work of the hunting party is to go out and follow the buffalo. And sometimes those buffalo led us to other people’s forts, and led us to other people’s encampments and their settlements. And there were those that we made peace with. And then there were those we made war with, or they had already made war with us.

Now, a company of Rangers had been tracking them back to the creek, to retaliate. The Rangers numbered about twenty, and they were joined by twenty other soldiers. They were led by a 22-year-old Ranger captain named Sul Ross.

It had been more than a decade since Jack Hays left to seek his fortune in California. Ross was part of a new generation of Rangers, and he became a legend in his own right. In one summer break when he was back from college, he joined a battle against the Comanche and was seriously wounded.

Just two and a half years after that, Ross was back in North Texas as a Ranger captain, with orders from Sam Houston to defend settlements from the Comanche. Early on, Ross decided that he wasn’t just going to play defense. He was going to take the fight to the Comanche.

On that December morning, while the Comanche were packing up camp, Ross led a charge. He recalled later that, quote, “the attack was so sudden that a considerable number were killed before they could prepare for defense.”

It was a bloodbath. Ross and his men fired on the tribe, killing men, women, and children. After the shooting stopped and the survivors were taken prisoner, something about one of the women caught Ross’s attention.

Dustin Tahmahkera: And they see her, and they wonder, from the blue eyes and the fairer skin, that if this could be the famous Cynthia Ann Parker that they had heard had been taken captive and was raised Comanche.

It was a sensation in the press. Sul Ross became a hero, and the Battle of Pease River became famous. Reporters wrote how Ross rescued Parker in a daring raid on the Comanche. It’s portrayed as a great battle, a turning point in the Rangers’ war against the Comanche. As one writer, James T. DeShields, would remark years later, “So signal a victory had never before been gained over the fierce and warlike Comanches.”

Along with Cynthia, the Rangers took a young boy prisoner at the Battle of Pease River. Ross ended up taking him home. He named him Pease. Ross had previously adopted a young white girl he had rescued from Comanches, naming her Lizzie and raising her as a daughter. But Pease was dark-skinned, either Comanche or Mexican. And by some accounts, Pease became a servant in Ross’s house. It’s a blurry line between caretaker and captive-taker.

Today, Sul Ross is in the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame, which commends him for his, quote, “skill and courage.” He went on to serve two terms as Texas governor.

But for Naduah, or Cynthia Ann Parker, the Battle of Pease River hadn’t looked like a battle: her family had been massacred. In 1928, one of the Rangers who was there, named Hiram B. Rogers, told an interviewer: “I was at the Pease River fight, but I’m not very proud of it. That was not a battle at all, but just a killing of women.”

Cynthia, forcibly taken back to her white family and paraded around in the press, was inconsolable.

Dustin Tahmahkera: But our accounts say that she was brokenhearted, and that she repeatedly tried to get back to her Comanche family. That’s something that I think anybody who loves their family, you know, might be able to identify with and sympathize with.

Naduah never adjusted back to Anglo life. Dustin says she was heartbroken at the loss of her sons and husband and felt alienated by all the attention she received.

She had just one connection to her old life, her daughter, Topʉsana, or Prairie Flower, who had been captured with her. But when the girl died from pneumonia, by some accounts, Naduah began refusing food and water. She starved herself to death.

Jack Herrera: I mean, for me, it’s an incredible story, and really gets to the idea of what it means to be Native, and what it means to be one of the people. For Quanah, what it is to navigate both sides of heritage. And then also, the morality. When you go into this history and you try and figure out: Are the Rangers quote, unquote rescuing her, tearing her away from her people and shooting them in front of her, are they the good guys? Are the Comanche who abducted a child the good guys? Trying to apply that sort of Disney-movie morality to history, it just doesn’t—it breaks down. It doesn’t work.

Dustin Tahmahkera: Yeah. A white American mainstream readership sees these oftentimes-sensationalized accounts that tell horrific stories. And that becomes very difficult for folks to reconcile with a story like Cynthia Ann Parker’s, and the untold stories of countless captives who were captured by Comanches, raised Comanche, and even when they were given the opportunity to go back to an Anglocentric world, that there were so many—Cynthia Ann Parker included—who chose to stay with Comanches.

Naduah’s son, Quanah, was actually not killed in the attack. He would go on to become a leader, like his father. Along with the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Kiowa, Quanah fought against the U.S. Army for half a decade, refusing to back down.

Then the Americans began slaughtering the Native peoples’ horses, and hunters decimated the bison the Native people relied on. That’s when Quanah decided there was only one way to guarantee his people’s future. He led his band to the Fort Sill reservation, in Oklahoma.

Dustin Tahmahkera: And so he set forth a model in his own history of going from defending his homeland and fighting for his Comanche people and fighting for Comanche ways, and finally realizing, in 1875, that they were outgunned, they were outmanned—that it was time to reluctantly go onto that reservation.

Some Native people criticize Quanah’s leadership.

Dustin Tahmahkera: But I come from the Quahada band. All the Quahada relatives I know recognize Quanah, and thank him for making that decision. And if he had not done that, we very well may not be having this conversation today.

The Rangers declared victory. The great Comanchería was gone. But after peacefully leading his people to the reservation, Quanah doesn’t disappear.

Dustin Tahmahkera: I mean, he’s a celebrity. He hosted Theodore Roosevelt. He, in turn, went to the White House, and kept building these bridges and continued to defend his homeland—but did it with these new weapons of the intellect and trying to get policy passed.

He even performed as an actor in early movies and traveled the country giving speeches. As he grew older, he saw the ways Texans were telling the story of the founding of Texas and their fight against the Comanche. And it bothered him.

Dustin Tahmahkera: I think the last public speech he gave, right before he passed, was at the Texas State Fair. And he told audiences, at least the way it got recorded in local newspapers there in Fort Worth and Dallas, he said, “I challenge you to go forth and tell Texas history straight up. Texas history straight up.”

That was the work that occupied Quanah in the last years of his life. And when Quanah died, his children carried it on, and their children too. Dustin, too, is carrying on this family work. Because—while his old classmates were boasting about their ties to Comanche royalty, what Dustin didn’t say as he sat in the back of the room was that he is the great-great-great-grandson of Quanah Parker.

Dustin Tahmahkera: Being told from as early as I can remember that you are Nʉmʉnʉʉ, you are Comanche, you come directly from Quanah Parker—and when you hear others speaking about Comanches, to do your best to speak up and to remind people that we’re still here.

Today, Dustin is a media scholar. He’s dedicated his research to how Comanche appear on-screen. Often, Hollywood studios will ask Dustin about how to accurately portray Native people—he recently consulted on the movie Prey. When he talks with producers, he makes the same challenge his ancestor, Quanah Parker, once made: tell history straight up.

[Crunching sound of footsteps]

Jack Herrera: I’m deep in West Texas, in the shadow of the Guadalupe Mountains, the tallest peaks in the state, rising up in steep rock faces above me. And underneath my feet is the mother lode of one of the most precious resources in this whole area, which was enough to start a war. Can you guess what this resource is? I’ll give you a hint. Let’s see if you can hear it crunching underneath my feet. It’s salt.

I’m standing on salt beds, two hours north of the border town of San Elizario. I’m here because it’s a place that—maybe more than anywhere else in the state—explains how and why the Texas Rangers came to see some Tejanos and Mexican Americans as their enemies.

It happened around the same time Quanah Parker led his people to the Fort Sill reservation. About forty years after Texas independence. For former Mexican citizens, life along the new border with Mexico hadn’t changed all that much: pretty much everyone still spoke Spanish and used pesos. The same farmers owned the same land. The same ranchers grazed cattle on the same pastures. Many former Mexicans were wealthy and owned huge haciendas. But under the Mexican legal system, some of the most important land was communal property—like the salt flats I’m standing on. No one owned them, because everyone owned them.

Today, you can get salt . . . pretty much anywhere. But in the 1870s, in the deserts of West Texas, salt was precious.

Jack Herrera: Salt was a way to cure meat, to cure animal hides—tan animal hides. And for farmers, during years of bad crops or in the off-season, you could harvest the salt and ship it out and sell it at a market, and cover your expenses during a poor harvest or just a bad year.

So they’d harvest the salt there, wrap it up in packages called fanegas, and haul it in wagons around seventy miles to San Elizario. It was a grueling two-day journey back then. In my rented Jeep, I made it in about an hour and a half.

Oscar Navarro: You know, nowadays, we go to McDonald’s or whatnot, and they oversalt our fries. And here we’re shaking off that salt. And here’s a point in history where people actually did die for salt.

That’s Oscar Navarro. He’s a local historian and director of Los Portales Museum, in San Elizario. As we speak, we’re standing in the museum, which is an adobe building that’s over 150 years old. It’s a hot afternoon outside, but it’s cool inside these three-foot-thick walls.

Back in the day, this was actually the home of the Texas Ranger captain Gregorio Nacianceno Garcia, a leader of the Frontier Forces. San Elizario had been the county seat, one of the most important towns in West Texas.

As we walked through the building, Oscar explained how life changed in San Elizario after the Civil War. Newcomers—mostly Anglos—began arriving and making land claims. It led to serious tensions. Oscar says it’s not just that they were trying to claim land that had historically belonged to Mexicans. It’s that their values clashed with residents’ understanding of themselves as a pueblo. These newcomers didn’t respect the tradition of communal lands.

Oscar pointed to a photo on the wall.

Oscar Navarro: This is Charles Howard, who is the main antagonist in this story.

Jack Herrera: Yeah.

Charles Howard was a Confederate veteran from Virginia. He arrived in San Elizario with a plot in mind: he wanted to claim the salt beds, and then make the people of San Elizario pay him every time they harvested the salt.

This all kicked off an intense, tangled West Texas Game of Thrones. Howard tried to form alliances with the powerful men in town, but it didn’t end well. Howard made a few allies, stabbed some other guys in the back. At one point, Howard walked into an El Paso store and shot a man in the chest. And it all culminated in what’s today called the San Elizario Salt War.

It’s not a well-known piece of state history, but Oscar says it tells us a lot about what things were like in the Texas borderlands at the end of the 1800s. And it becomes a big moment in the history of the Rangers.

Oscar Navarro: We got race relations, we got outsiders coming in, and we have the necessity of what is substantial for life as a human being.

In late 1877, two men openly defy Howard and announce plans to ride out to the flats and load up their wagons without paying him.

Oscar Navarro: ’Cause people knew he was doing this, but they were in dire straits as it was. And also out of defiance as well—like, what is this guy from outside coming in to tell us how to get the salt?

Jack Herrera: So it’s both an act of necessity—like, “This is our livelihood; this is how it’s always been”—but then also an act of defiance, like, “We’re ignoring your deed; we’re ignoring that you’re enforcing a price for fanegas. We’re just going to go collect salt.”

Oscar Navarro: Correct.

Howard is outraged.

Oscar Navarro: Howard comes in and demands that these two men are arrested. And this is the lynchpin that sets off the beginnings of what is the Salt War.

San Elizario explodes. The townspeople are furious, and they run Howard out of town. It turns into an open, armed revolt. But Howard doesn’t give up. He sends word to Austin, the Texas capital, asking for backup.

Oscar Navarro: Howard by this point has that kind of political power, and he’s asking for help from the Rangers to come in and, kind of, like, “Help me out. ’Cause things are starting to get a little crazy down here.”

The governor of Texas responds by sending a company of Texas Rangers, led by Captain John B. Jones. Jones was another former Confederate soldier, who went on to lead the Rangers’ Frontier Battalion in a campaign against the Comanche, Kiowa, and Apache. He was also famous for capturing outlaws—he was the leader of the Rangers who killed the famous outlaw Sam Bass, after his gang pulled off one of the most famous train robberies in American history.

But when Jones rides into San Elizario, he chooses to keep his guns holstered. He wants to try diplomacy this time. He approaches the men who’ve become the informal leaders of the revolt and tries to negotiate an agreement. One where they would obey Texas laws—including laws governing private property.

Oscar Navarro: And he negotiates a shaky treaty between the communities of San Elizario and the people dealing with Howard.

Jack Herrera: Yeah, so he doesn’t come out—he doesn’t ride into town shooting. He comes in and tries to play diplomat.

Things are tense. All this time, Mexicans have been coming into San Elizario, from towns around West Texas and northern Mexico.

Oscar Navarro: There is a storm a-brewing, and Jones realizes, like, he can only do so much without inciting violence. And he’s able to do some stuff, but he goes back to Austin saying, “Okay, I was able to do it.”

Jack Herrera: “Yeah. We talked it through; it’ll be good.”

Jones leaves, but he wants to maintain some sort of Ranger presence in San Elizario. He commissions a new company of twenty Rangers, a scrappy group that included some local Confederate veterans, a couple wagon drivers, a teenager, and even one outlaw.

And after Jones has left, these Rangers have the job of escorting Howard back into San Elizario. But Howard still demands that the residents pay for “his” salt.

When Howard and the Rangers arrive at the Rangers’ barracks in San Elizario, they’re suddenly surrounded by angry townspeople.

Jack Herrera: So where are we standing?

Oscar Nararro: So this used to be the Texas Rangers’ house. It used to work—it used to actually have a lot of different uses. It used to be the post office. There used to be a mercantile store in here as well.

It’s a two-story adobe building. Today it’s a community library. The walls are white but dusty, and there are cracks through some of them. But it’s in surprisingly good shape for a building that’s been around for 150 years.

Oscar Navarro: For our time period, this was the Texas Rangers’ house. And this is where the people, the community surrounded the area.

With the Rangers holed up inside, people continue pouring into town. Eventually, as many as six hundred people surround the walls. For days, the armed crowd kept the Rangers pinned down. I tried to imagine what it must have been like.

Jack Herrera: They’re basically like, I mean, imagine they’re on both floors. They’re got rifles off the windows. They’re trying to hold people off from charging. Then imagine, so then, it’s probably just the whole ring of like, we’re looking around here, just like, you know, hundreds of people lined up around, probably outside of rifle distance, just surrounding it.

Oscar Navarro: Right. And there used to be a gate around this area. So this is another adobe gate. So this is where they were also taking watch, to see if anybody would break their perimeter.

Jack Herrera: ’Cause, I mean, you can’t, you can’t be sleeping, ’cause they’ll get in. So you have to like, you know, sleep in shifts.

Oscar Navarro: They’re held up here for four days until, you know, they come to the realization—especially Howard—that they’re gonna lose. He realizes that they’re gonna—they want him, and he’s gonna give himself up to essentially save these other guys from being killed.

They surrender. And you have to understand what this means—since their founding in 1823, the Rangers had never surrendered in a battle: not to Comanches, not to the Mexican Army. But in San Elizario, they gave themselves up to Tejanos, who were fighting for their way of life.

Jack Herrera: So they walk through that thick adobe walls; they walk out. Hundreds of people are here, pretty much a lot of them armed. What happens?

Oscar Navarro: So Howard is the one that goes first. And he is actually put—this used to be a residence right across the street from us.

Oscar points at another beautiful adobe building across the street, an old mill that houses art galleries today. He says that’s where Howard is taken, and he’s joined by two of his local allies who had also been holed up with the Rangers.

Oscar Navarro: And they were put in one of the rooms in there to be held. Yeah. And then, slowly, they negotiated to get the Rangers out of here, to surrender.

And, without the Rangers, there was nothing to protect Howard from the crowd.

Oscar Navarro: Yeah, so, this is already December, and it’s cold here. People are hungry, and people are angry. And so, what ends up happening is that they get Howard and the other two men, and so they actually bring him out, and across the street from us, they set up eight men and actually set him there, and he’s like, “Okay, go ahead and kill me.”

Oscar showed me the wall where they forced Howard to stand. It’s a white adobe wall, lined with prickly pear cactus, with a veranda shaded by cottonwood beams and mesquite.

Oscar Navarro: Well, remember, he used to be a Confederate soldier. He is hardened by war already. So he has accepted his fate. And so, you know, instead of letting them take charge of his destiny, he tells them, “Okay, go ahead and fire.”

Jack Herrera: So he gives the order to fire.

Oscar tells me that Howard didn’t have a good death.

Oscar Navarro: He doesn’t die right away.

Jack Herrera: Oh, man. So he has been shot—at least a few, a few bullets, you know, had any sort of aim.

Oscar Navarro: You can see him on this road. You can imagine this portly man bleeding out. And so, one of the gentlemen from Socorro comes in with a machete, tries to hit him in the head with it. He’s so excited, he misses and actually chops his own toes off on one of his foot. Howard just is in writhing pain, and he looks at one of the members in the community and just tells him, “Just end me, please.” And a gentleman shoots him in the head with a revolver at that point.

The news spread all around Texas—and the country.

Oscar Navarro: So everybody, even up to Washington, is hearing what’s going on here. So if you go research throughout this, like, we’ll see articles from Chicago or stuff like that, describing this area as a bunch of violent barbarian Mexicans in mud huts, killing Anglos.

Washington sent soldiers to West Texas. Texas sent more Rangers. And right across the border, Mexico would soon descend into a revolution. It all set the stage for the darkest chapter in Ranger history.

Next time on White Hats:

Arlinda Valencia: And we said, “Uncle John, the Texas Rangers don’t go around killing people; they’re supposed to be helping people. And so we just said, “Let’s start looking for evidence. If it happened, there’s got to be something out there that’s going to prove it.’ ”