Listen to this episode on Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher | Google. Read the transcript below.

Subscribe

By sealing that document for fifty years, there was a very vivid hope there would be no further inquiry. Whatever the official story was, that would be the official story.

—James Sandos

One year after the Porvenir massacre, the Texas Rangers are a subject of an inquiry at the Texas capitol led by state representative J. T. Canales. In this episode, we hear testimony from the hearings about the Rangers’ violence, as well as attempts by Rangers backers to discredit Canales and his effort. After the hearings, the Rangers only become bigger heroes in popular movies and TV shows. But the stories of their violence against Mexican Americans live on in South Texas, in oral histories and corridos, and resurface during the civil rights movements of the sixties and seventies.

You can read more about the stories in this episode in The Injustice Never Leaves You: Anti-Mexican Violence in Texas, by Monica Muñoz Martinez, and Texas Ranger: The Epic Life of Frank Hamer, the Man Who Killed Bonnie and Clyde, by John Boessenecker.

Special thanks for research help on this episode goes to the Legislative Reference Library of Texas and the Voces Oral History Center at the University of Texas at Austin.

White Hats is produced and edited by Patrick Michels and produced and engineered by Brian Standefer, who also wrote the music. Additional production is by Isabella Van Trease and Claire McInerny. Additional editing is by Rafe Bartholomew. Our reporting team includes Mike Hall, Cat Cardenas, and Christian Wallace. Will Bostwick is our fact-checker. Artwork is by Emily Kimbro and Victoria Millner.

This episode features additional field recording by Katie McMurran.

Archival tape in this episode is from the 1934 news film “The Retribution of Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker” (from Jamieson Film Company via the Texas Archive of the Moving Image) and the University of Texas at San Antonio Institute of Texan Cultures Oral History Collection.

Transcript

I want to tell you the story of a cover-up—one that lasted almost sixty years—and the guy who exposed it.

James Sandos: And actually kind of happenstance—I was looking for something else, and that’s frequently the way it is when you’re doing archival work. You stumble upon something that you weren’t expecting.

That’s James Sandos. In 1975, he was back from Vietnam, and he was a graduate student at UC Berkeley. He was researching cross-border raids by Mexican revolutionaries in the 1910s. And at the National Archives, he’d seen a report on the Texas Rangers’ role on the border. It was a transcript of hearings at the Texas capitol, split into three folios—but the third folio was missing.

James Sandos: And the one that was missing seemed to have all the information about Ranger activity. . . . Why isn’t it there?

James thought that the complete report might still be in Austin. So he went to take a look.

In the middle of what was still a sleepy college town, the Texas State Archives and Library is a grand, imposing building right next to the Capitol.

James Sandos: I thought, “Boy, this is on a par with the archival storage facilities in Washington, D.C.” I thought, “You know, whoa, these people take their history seriously.” And they did, and do.

Inside, he flipped through the card catalog . . . and found the report. All three volumes.

James Sandos: And I was told, “Well, you know, the Canales investigation is closed, and it won’t be open for fifty years.” And I said, “Excuse me. This is 1975. The investigation was in 1919. I think, even in history, you got to do the math.” And she went downstairs and talked to some people, and she came back an hour later and said, “Well, I guess you’re going to get to look at it.”

James wondered what was so delicate that it had to be locked away for half a century.

James Sandos: It was on a cart, and she had somebody helping her pull the cart.

It was more than 1,600 pages, from 1919. James began to read.

James Sandos: I was just—I was stunned. I was stunned at what I found.

In the third volume, he found testimony about dozens of instances of Ranger attacks, crimes, and murders. Testimony from survivors of Porvenir.

James Sandos: It was just boom, boom, boom. I thought, “This is incredible.” That was my first thought. The second thought is, “No wonder they wanted to keep this sealed for as long as they could.”

According to James . . .

James Sandos: By sealing that document for fifty years, there was a very vivid hope there would be no further inquiry. Whatever the official story was, that would be the official story.

In this episode, we’re going to find out how that happened—how that official story took hold. And how this other version of events—even though the state locked up the records—survived anyway.

From Texas Monthly, this is White Hats: a story of the legendary Texas Rangers and a struggle for the soul of Texas. I’m your host, Jack Herrera.

This is episode four: “The Cold Case.”

Back in 1918, as La Hora de Sangre continued to rage in South Texas, one Texas lawmaker began to hear disturbing reports. His name was José Tomás Canales. He’s the man behind the Canales investigation, those shocking documents James Sandos found in 1975.

Monica Muñoz Martinez: At the time, he’s the sole Mexican American elected state representative.

This is Monica Muñoz Martinez.

Monica Muñoz Martinez: He’s from Brownsville and starts receiving complaints about violence by Texas Rangers.

Monica is a professor at the University of Texas, in Austin.

Monica Muñoz Martinez: So, I’m a historian of U.S. history, of race relations in the U.S. My primary research is focused on Texas and the history of racial violence in Texas.

Monica has spent more than a decade researching the Porvenir massacre. And she explains that, in the year after it happened, Canales began working for justice for the survivors and other victims of Ranger violence.

He heard stories of prisoners who’d been taken by the Rangers from local sheriffs and shot in the brush. Of people who’d been pistol-whipped and tortured. And of a small village of Porvenir, where Rangers had killed fifteen men. Canales tried to raise the alarm in Austin.

Monica Muñoz Martinez: He very much believes in the system, and his ability, as a politician, to go through the proper channels—you know, writing to the adjutant general, writing to the governor—to try to get help in curtailing these acts of violence by Texas Rangers.

Canales was a gentleman. He was born in 1877 on his family’s ranch, a large estate outside of Kingsville. The Canales family had roots in Texas deeper than the state itself: they were Tejanos, whose claims to the land went all the way back to the Spanish crown. He studied law at the University of Michigan and entered the Texas state House as a Democrat in 1905. He represented the area around Brownsville, the lush border town where the Rio Grande empties into the Gulf of Mexico.

The Idár family in Laredo—the newspaper publishers you heard about in the last episode—they actually wrote about Canales and the discrimination he faced in the Capitol. In a story that describes how Mexican people were denied service at shops, or denied the right to vote, they write that even Canales’s fellow lawmakers had called him “el mexicano ceboso.” The greaser Mexican.

But he was also insulated, in part, by his own enormous wealth. In Austin, he went by Joe.

Monica Muñoz Martinez: He’s from a wealthy Tejano family. His wife is white. Right? So in this era, when you see all of these Jim Crow, Juan Crow laws being passed, all of segregation being built into the institutions, he flies in the face of all of that.

For months, Canales asked the governor to rein in the Rangers. But the governor put him off with false promises, and officials in Austin worked to undercut him. And as word spread that Canales was investigating the Rangers, it earned him enemies. In December, almost a year after the Porvenir massacre, a Ranger approached Canales in the border town of San Benito. He was over six feet tall and around 230 pounds, and he had a violent reputation. His name was Frank Hamer. And he had a message for Canales.

Monica Muñoz Martinez: And essentially, you know, threatens him. Like, if you go through with this, you’re gonna regret it.

But Hamer’s threats motivated him: the lawmaker gave up appealing to the governor and took matters into his own hands. Less than a month after Hamer confronted him, Canales introduced a daring piece of legislation.

Monica Muñoz Martinez: So, he is in the company of others who are saying, “We’ve got to stop—we have to stop this violence by the Texas Rangers.” He gains enough support to pass HB 5, which is a bill that calls for a hearing and investigation into the Texas Rangers. It’s also calling for the same kinds of reforms that you hear about people advocating today. That Texas Rangers should be under bond. That you should increase their wages, so that you have a more competitive pool of people applying for these positions. But also that you reduce the force, and you eliminate having these people who have these bloody records from being on the force.

But lawmakers were outraged by even a hint of criticism against the Rangers. They accused Canales of lying and demanded that he produce evidence.

Monica Muñoz Martinez: And so what you get is two and a half weeks of over eighty witnesses coming in either to support the Texas Rangers and endorse their practices, or violent practices, or to bring evidence of harms that they have caused; murders that they’ve committed; participating, you know, in torture of prisoners.

In a room at the state capitol, a handful of lawmakers listen and question witnesses. Canales actually isn’t on the panel, but he’s allowed to join in and ask questions. He and other witnesses sit in the room with the same men they’re accusing. Canales worried about assassination attempts. And outside the Capitol, Frank Hamer had stalked Canales around Austin—reminding him that he was watching.

But Canales succeeds in getting accounts of the Rangers’ brutality committed to the official record. Witnesses came from all backgrounds. An Anglo woman complains about Rangers’, quote, “reign of terror” in South Texas. An Anglo judge describes how a Ranger captain, who seemed to be drunk, approached him in the courthouse and pistol-whipped him.

That Ranger captain was named John J. Sanders. Sanders took the stand and admitted that he attacked the judge. He said he felt justified because the judge had published writing that condemned the Rangers’ attacks on Mexicans.

Canales introduced more charges of his own: that Rangers tortured a Mexican American man in Duval County; that they murdered others in Cameron County and Rio Grande City. The eleventh charge he brought is one you’ve already heard. Canales read it to the record: he said, “I charge that on January 28, 1918, fifteen Mexicans, after they had been arrested and disarmed by the State Rangers at El Porvenir in Presido County, were murdered by said Rangers without any justification or excuse.”

By this time, more than a year had passed since the massacre. And throughout, the Rangers of Company B had proclaimed their innocence. An El Paso newspaper had reported on the massacre but claimed that the massacred villagers were “raiders” and “squatters.”

But the real story still got out: the survivors fled into Mexico and told officials there what had happened. Mexican officials complained to Washington. And eventually, under pressure from both federal governments, Texas governor William Hobby dismissed five of the Rangers and pushed Captain J. M. Fox for his resignation.

But to the survivors of Porvenir, this was still not justice. Canales’s hearings in Austin gave them another chance. Lawmakers read a long collection of their testimonies. There was 66-year-old Juan Mendez, who recalled, quote, “The dead bodies were left lying in the same place where they were. . . . The bodies had been shot straight through, and in their heads.”

And Pablo Jiménez explained that the men killed “were peaceable citizens, and dedicated completely to their work.”

For years, Rangers had been killing people of Mexican descent with near impunity, as the English-language press cheered them on for stopping “the bandits.” Now, thanks to the state House’s only Tejano member, survivors were getting to tell their side of the story, in the Capitol, in the public record.

But the Rangers fought back. The Rangers had a legal team at the hearings, and this was their strategy: instead of letting the hearings proceed as an investigation of the Rangers, they would use them as an opportunity to take down the Rangers’ most powerful critic: Canales.

Monica Muñoz Martinez: You know, the lawyers for the Texas Rangers say, like, “We need to question this guy’s motives, to see why he is bringing these charges.” And so they smear him. They make these accusations that, you know, because he has Mexican blood in his veins, that he is unconsciously loyal to Mexico, and not to the United States.

One of the Rangers’ lawyers asked Canales, multiple times, if he was, quote, “by blood a Mexican.” Canales replied, “I am not a Mexican; I am an American citizen.” But the Rangers’ attorney declared, quote, “Blood is thicker than water.”

The lawyers also questioned Canales’s mental state. They suggested he’d imagined that Hamer had threatened him in Austin. They said: “Now, isn’t it a fact, Mr. Canales, that you have become obsessed, in a way, with suspicion and hallucination regarding the seriousness of this matter?”

Monica Muñoz Martinez: They publicly go out of their way to try to humiliate him, to call him to question. And it’s a hard transcript to read—the sort of disdain they showed for him.

Canales isn’t the only person the Rangers’ lawyers attack. They throw doubt on essentially everyone who challenges the Rangers. After Canales introduced the charge of the Porvenir massacre, the lawmakers read the account of Fox, the captain of Company B Rangers, that described the massacre as a shoot-out with bandits.

Monica Muñoz Martinez: And Fox continues to contest it. And what he’s also contesting is not, you know, in the end, that the massacre happened, but, like, what’s wrong with it?

And that idea—“What’s wrong with it?”—permeated the entire Canales investigation.

Captain John Sanders, who had pistol-whipped that judge, explained that residents on the border were terrified because they’d heard that Mexican mobs were coming to rob the banks and burn the towns.

A U.S. congressman from West Texas—named Claude Benton Hudspeth—offered his own philosophy for survival along the border. He told lawmakers that to, quote, “put down this lawlessness, you have got to kill those Mexicans when you find them, or they will kill you.”

Today, the county to the west of Porvenir is called Hudspeth County, after that congressman.

Through all of this, Canales keeps his cool. He tells the lawmakers that, even with the harm they’ve caused, he still believes in the Rangers. He says that “knowing the Ranger force as I do, I know that we need the Rangers.”

Monica Muñoz Martinez: Yeah, he’s a complicated figure. And one of the ways that he actually tries to defend himself when he’s being interrogated is actually by saying, like, you know, “I fund Texas Rangers, and I support them.” And he refers to the era of Texas Rangers from the late nineteenth century as, like, the good old days, right? That’s like when Texas Rangers, they are committing murders and massacres of Mexicans, but they’re also committing acts of brutality against Indigenous people.

Canales isn’t just being diplomatic. He had close friends who were Rangers. And he says he feels caught “between the devil and the deep blue sea”—between those who want to abolish the Rangers and those who want to put them on a pedestal. All he wants, he says, is to “purge” the Rangers of what he calls their “bad element.”

Canales says, “I am not here to protect any Mexican bandits. . . . [But] if a man is murdered, another man shouldn’t be murdered.”

After twelve days of testimony, the hearings come to a close.

Monica Muñoz Martinez: And they release a report. Their findings are that there were absolutely some civil rights abuses by Texas Rangers, that they absolutely committed some horrific acts of violence, but that on the whole, that Texas Rangers did the best that they could in violent circumstances. And so the committee buys into the version that the lawyers for the Texas Rangers submitted, that South Texas is a violent place, that Mexicans are inherently violent people. And that to control those populations, you have to use force.

In 1925, Captain J. M. Fox was welcomed back into the Ranger force. Other Rangers who’d been dismissed for their role in the Porvenir massacre were also reinstated.

Monica Muñoz Martinez: And so what you don’t see is any prosecution. So in the cases when there’s clear evidence of Texas Rangers participating in murders, the committee doesn’t call for those Texas rangers to be prosecuted.

For survivors, like Juan Flores—who you heard about in the last episode—it must have been a heartbreaking moment: over a year after the massacre, after rounds of painful testimony, he and his family had nothing to show for it. No justice.

Monica Muñoz Martinez: Juan Bonilla Flores is somebody whose life I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about. So here’s this child who’s just experienced this massacre, you know—then he’s tasked with going to get the teacher, going to get Warren, for help. And then Juan has to participate in this act of identifying the remains of his father. And so the kinds of injustices that people feel are multiple. It’s not just the injustice about the massacre itself, but it’s the injustice of the failure to fully acknowledge and reckon with the harm caused. And so, instead, you have the racist tropes of Mexicans continue. And the other thing that happens is that these investigations, these volumes are not made public.

After the hearings, Canales began working for change outside the Capitol. In 1929, he joined other Tejano progressives—including Jovita Idár’s brother, Eduardo Idár—in founding LULAC—the League of United Latin American Citizens. Today, it’s the oldest, and largest, Latino civil rights organization in the country.

And Canales did win some meaningful reforms at the Capitol. After the hearings, the Ranger force was reduced, pay was increased, and the state created new requirements to become a Ranger. And Monica says that, after the Canales investigation, the Rangers made an effort to move on.

Monica Muñoz Martinez: And so, the sort of convenient version of this history—the whitewashed version of this history—is that there’s this hearing in 1919; hundreds of Texas Rangers are let go. And the Texas Ranger force moves on, and it professionalizes. And so Hamer becomes a symbol of this kind of progression.

Frank Hamer. The same guy who threatened J. T. Canales. He becomes one of the most celebrated Rangers in Texas history.

If you know any Texas Rangers by name, you’ve probably heard of Frank Hamer. They’re still making movies about him.

Lee Simmons: Was a time we put a couple of man-killers on the pair and let them do their job.

Ma Ferguson: This is 1934, Lee, and you wanna put cowboys on Bonnie and Clyde? Is that what you’re sellin’?

Lee Simmons: Frank Hamer. That’s what I’m selling.

That’s from the movie The Highwaymen, from 2019. Kevin Costner played Hamer.

That movie—and Hamer’s legend—isn’t about the 1910s, when Hamer fought in the Bandit Wars and threatened Canales. Hamer had a long, storied career.

John Boessnecker: He, in my opinion, was the greatest American lawman of the twentieth century. Nobody had a career that came close to Frank Hamer’s.

That’s John Boessnecker. He wrote a best-selling biography of Hamer in 2016.

Francis Augustus Hamer was born in 1884 in Fairview, Texas, just north of Dallas. As a boy, he read stories about the Rangers’ battles against the Comanche and Kiowa, and, in 1906, he joined a Ranger company in South Texas, patrolling the Mexican border.

John Boessnecker: He had no intention of ever going into law enforcement, but he was an expert horseman, an expert cowboy in West Texas, a crack shot, and incredibly intelligent. He only had a sixth-grade education, but he was naturally intelligent.

Hamer served along the border under Captain J. M. Fox in the conflict Rangers called the Bandit War. And Hamer saw some of its most brutal action. The rebel sedicionistas derailed a train, attacked ranches, and killed indiscriminately. Hamer saw the terror they had inflicted on South Texans.

It was Texas governor James Ferguson who’d dispatched Fox—along with Ranger captain Harry Ransom—to deal with the insurgency in South Texas. Both men already had bloody reputations. Ferguson told them to do whatever it took to stop the violence—and he said he’d pardon them if they broke any laws.

From his letters, we know how Hamer felt about these two men.

John Boessenecker: I think that Hamer was disgusted with both Captain Fox and with Captain Ransom. Hamer had multiple encounters with both of them and strongly disliked them and believed they’d brought terrible discredit to the Ranger service.

Even though Hamer served under Fox, John says it’s important to understand that Hamer wasn’t at Porvenir.

John Boessenecker: Hamer certainly had controversial aspects to his career and certainly made some terrible errors of judgment during his career, but none of them were taking part in these “evaporations.”

Hamer saw the aftermath of the largest battle of the Bandit Wars. In 1915, about fifty insurgents attacked a railroad stop at the King Ranch—the biggest, richest ranch in Texas. The battle was called the Norias Raid. For hours, Fox and the Rangers exchanged gunfire with the rebels.

The fighting had already ended when Hamer arrived. With Fox, he searched the area, looking for any rebels who had escaped. Using his Winchester rifle, he pulled open the door to a shack. The sight that greeted him was horrific: on the floor was the body of a Mexican woman. The back of her head had been shot off by the rebels. A group of Mexican railroad workers huddled next to her, surrounded by her blood.

In South Texas, Hamer and the Rangers felt like they were fighting a war, rather than acting as police.

John Boessenecker: If you look at it as a military expedition carried out on the Mexican-Texas border . . . you know, the special forces, when they ambush a patrol of ISIS fighters, they open fire. They don’t order them to surrender.

Like many Rangers, Hamer believed that the only way to stop the rebels was with a shock and awe campaign. And after the Norias Raid, he tried to send them a message.

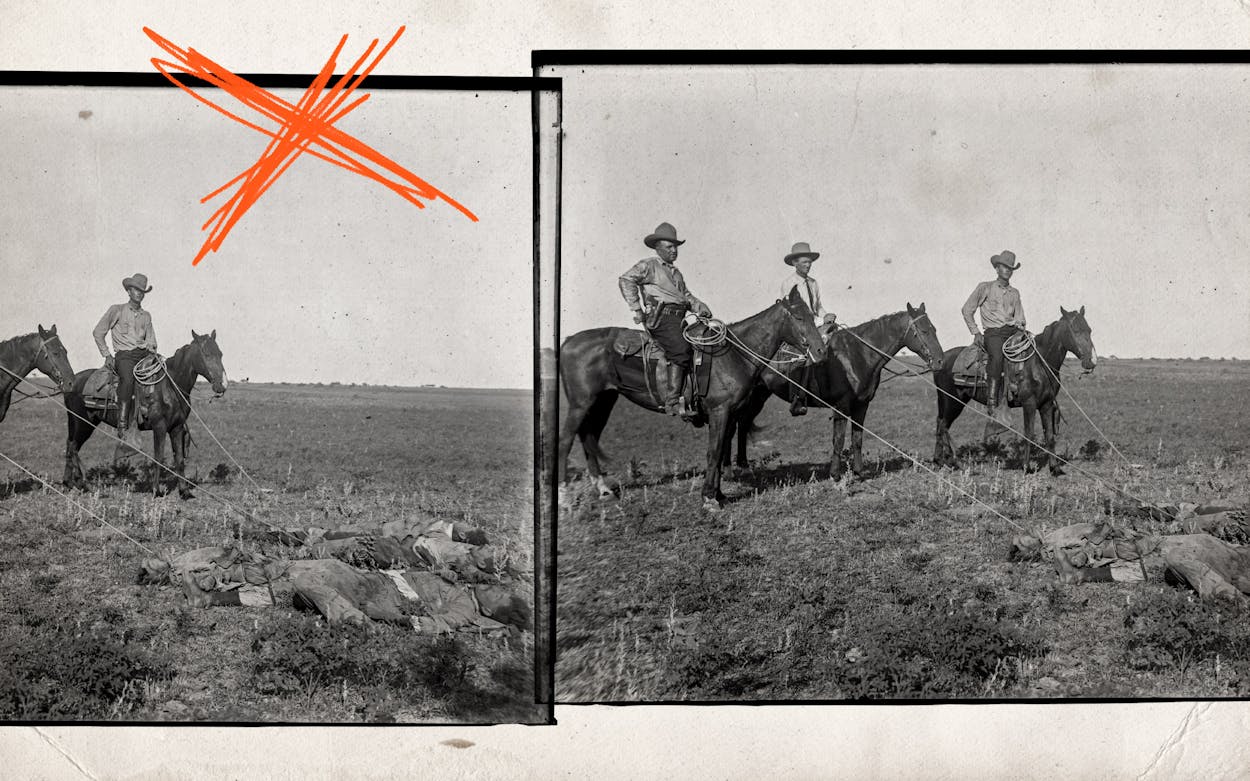

John Boessenecker: And in the morning, Hamer and Captain Fox and some other men posed for photographs where they had lariats looped around the bodies of several of these dead rebels, or bandits, depending upon how you look at it. And these were widely sold throughout the border region, even in northern Mexico. And they just enraged the Latino population, because it was a picture of the very complaint against the Rangers mis-abusing Tejanos.

This was a time when postcards of Black men being lynched were sold in stores across the South, and, understandably, many people in Mexico and South Texas interpreted the photo as an image of Texas Rangers lynching Mexicans.

John Boessenecker: It was one of the biggest blunders of his career, was to pose for that photo. And during the later Canales hearings, one of the U.S. Cavalry officers testified that those photos did a tremendous amount of damage, because it incited feelings against Texans by people in northern Mexico.

After the Canales hearings, as dozens of Rangers were fired and the force was professionalized, Hamer was one of the Rangers who managed to keep his job. But now the Rangers were changing, and he had to change too.

John says you can see this new chapter begin in—of all places—a meeting of the Ku Klux Klan.

John Boessenecker: And his friends come and invite him to a meeting of the Klan, and they tell him it’s to support law enforcement. And Hamer says, “I’m all for anything that supports law enforcement.” So he goes to the meeting, and partway through the meeting, they bring up an African American prostitute, and they start planning in the meeting that they’re going to grab this prostitute and tar and feather her and ride her out of town on a rail. And Hamer listens to this for a few minutes, and he stands up, and he says, “If anybody in this room lays a finger on that woman, I’ll put him in prison.” And he stormed out of the meeting, and ever after he was a bitter enemy of the Ku Klux Klan.

John argues that Hamer did more than any other lawman in Texas to stop the practice of lynching in the state.

John Boessenecker: This is the Jim Crow era. He was a white supremacist, but he also believed in the civil rights of blacks, and he believed strongly against lynching. So during his career, he personally saved fifteen African Americans from lynch mobs, and then he led the fight against the Klan in Texas in the 1920s.

In one dramatic instance, a Black man in Waco had been accused of rape, and a lynch mob had surrounded the courthouse, looking to kill him.

John Boessenecker: And the sheriff and the county judge are pleading with them to break up. “You people have all lost your minds. Go home. Let the law take its course.” And a motorcar with five men pulls up to the curb. And this burly man wearing a fedora and carrying a Thompson submachine gun walks very quietly through the mob. He goes up the steps of the courthouse and he sits down on the top step, and he just swings the barrel of the Thompson submachine gun to face the mob. He doesn’t say a word. And suddenly people in the mob start saying, “That’s Hamer. That’s Captain Hamer. He’s killed twenty-five men. That’s Hamer.” And the mob just drifts away. But that was his reputation. Because at this point, by that time in the 1920s, he’s the most famous lawman in the American Southwest.

Abruptly, though, in 1933, the new Texas governor, Miriam “Ma” Ferguson, fired all of the Rangers. Her decision wasn’t about the Rangers’ methods, or about how modern Texas was changing. She just didn’t like them. They had supported her opponent, the last governor, in the election. And, for a moment, Texas was without its Rangers.

But in 1934, Hamer would crack the case that turned him into a Texas legend and helped resurrect the Ranger force.

[police car siren noise]

Narrator: Clyde Barrow, the most ruthless killer the Southwest has ever known, was granted a parole from the Texas State Penitentiary on February second, 1932. After Clyde had become a full-fledged killer and gone in for big-time crime, he met Bonnie Parker, waitress and wife of a convict. What attracted this strange pair to each other will never be known.

Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow were on a deadly spree of small-time robberies, prison breaks, and holdups across the country. This was the Great Depression, and in the press, they became outlaw folk heroes.

And Hamer came out of retirement, for one last big job. For months, he tracked Bonnie and Clyde. He went so far as to acquire the same 1934 Ford that they drove, and he slept in it, living on the road, just like they did. And on May twenty-third of that year, he was waiting for them in the brush, along with a posse of five other officers.

[yelling, gunshots]

Narrator: Death is at the steering wheel. The inevitable end. Retribution. Here is Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker, who died as they lived: by the gun.

The famous outlaws were dead. And the men who’d killed them had stepped into their spotlight. After decades as a lawman, Frank Hamer became a celebrity.

His long career tracks the same arc of the Texas Rangers: after surviving dozens of gunfights, he cracked his most famous case as an investigator: a detective following the clues.

When the Rangers were resurrected in 1935—under a new governor—this was their job description. As a branch of the new Texas Department of Public Safety, the Rangers became a modern police force—the state’s elite investigators.

Hamer’s heroics also coincided with a major history of the Rangers, written by a friend of his: Walter Prescott Webb. Webb is probably Texas’s most influential historian. And he wrote the first great history of the Rangers: The Texas Rangers: A Century of Frontier Defense.

The Bonnie and Clyde affair helped convince Texas it still needed real-life Rangers. But it’s Webb who made those Rangers into legends.

Webb dug into the Rangers’ own reports and wrote a history of the great Ranger leaders. Jack Coffee Hays. Leander McNelly. And Frank Hamer, of course. The book came out in 1935, and readers loved it. Hollywood even made it into a movie called The Texas Rangers.

Narrator: “These are the men called Texas Rangers, molded in the crucible of heroic struggle, guardians of the frontier, makers of the peace.”

But Webb’s celebration of the Rangers is one-sided; the book has been described as a “life of saints.” When I first read it, I assumed that Webb just didn’t know what the Rangers had done during La Matanza; that he’d never come across stories told by survivors of Porvenir. But I was wrong.

When James Sandos finally got the Canales transcripts unsealed in the seventies, the archivist told him:

James Sandos: “No one has seen this report since Walter Prescott Webb.” And I said, “Before he wrote his book on the Texas Rangers?” And she said, “Yes. That’s the only person who’s seen it since 1919.”

It’s not just that Webb included the Canales hearings in his research. Years later, he said the hearings were actually what motivated him to write his book.

Monica Muñoz Martinez: He’s not telling the story from the point of view of people who were massacred. He’s telling it from the point of view of the Texas Rangers. And so he’s justifying their actions.

It may not have been great history, but it was great entertainment. In the forties and the fifties, the Rangers had a real pop-culture renaissance.

Narrator: Texas Rangers—first to advance, last to retreat.

Lone Ranger: Hi-yo, Silver, away!

[gunshots]

Narrator: Firing hard with the speed of light, a cloud of dust, and a hearty “Hi-yo, Silver!,” the Lone Ranger!

As the country singer Tex Ritter put it:

Tex Ritter: I’ll bet there’s not a boy or girl in this whole country of ours who hasn’t thrilled to the stories of the Texas Rangers. The high principles and courage of that fearless little band of men will remain an inspiration to us, down through all the years . . .

In 1957, a state senator from West Texas—named Dorsey B. Hardeman—introduced an amendment saying, quote, “the Texas Rangers shall not be abolished.” It is still, today, actually against the law to get rid of the Rangers.

I had to ask Monica to help me understand: just forty years after Porvenir, how did the Rangers become bigger heroes than ever?

Monica Muñoz Martinez: It happens because somebody like Walter Prescott Webb doesn’t see the humanity of the victims.

But it’s Webb’s version of the Rangers that took hold. When Monica was taking seventh-grade Texas history, in the nineties, she says she didn’t learn any stories about Ranger abuse. Still, there were places where the stories survived. Sometimes, they survived in songs.

[“El Corrido de Gregorio Cortez” plays]

Jack Herrera: Did you grow up with any, like, folk allusions to what had happened in [the] early twentieth century to Mexican Americans and Mexicans at the hand of the Texas Rangers? Or is that totally revelatory when you start learning about it?

Monica Muñoz Martinez: It was totally revelatory. Although, I should say, I had heard the corrido of Gregorio Cortez.

“El Corrido de Gregorio Cortez”: Decía Gregorio Cortez / Con su pistola en la mano: / “No siento haberlo matado / Al que siento es a mi hermano . . .”

She’d heard a version recorded by one of the legends of Mexican norteño music.

Monica Muñoz Martinez: Ramon Ayala: he sang that ballad.

Jack Herrera: Talk about oral history.

Monica Muñoz Martinez: Yeah. You know, it’s a Mexican ballad tradition.

“Gregorio Cortez” tells the story of what happened on a ranch southwest of San Antonio in 1901. A sheriff got into an argument with a rancher and shot him. And in return, the dying man’s brother—Gregorio Cortez—shot the sheriff. Then Gregorio disappeared.

“Gregorio Cortez”: Decía Gregorio Cortez / Con su alma muy encendida: / “No siento haberlo matado / La defensa es permitida”

Monica Muñoz Martinez: And part of what was the sort of folklore around it was not only his brother being killed and him shooting a law enforcement agent, but that he had made fools of the Texas Rangers that were trying to hunt him down.

For ten days, Gregorio led hundreds of men, including Texas Rangers, on one of the largest manhunts the country had ever seen.

Monica Muñoz Martinez: And there was a, a sense of—for Mexican American populations that knew histories of oppression and violence and racism—that he was a folk hero.

So, while the official history of the Rangers was written by men like Walter Prescott Webb, about heroes like Frank Hamer, corridos helped another version of the history—Tejanos’ version of the history—survive.

In 1958, at the height of the Rangers’ popularity, an author from South Texas named Américo Paredes published a book about “Gregorio Cortez.”

Paredes was one of the first scholars in Texas to elucidate Mexican American identity. And his book, called With His Pistol in His Hand, helped inspire the Chicano movement.

Monica’s parents grew up during this time.

Monica Muñoz Martinez: They taught me and my sister to think critically about the way that issues around race or civil rights are framed in the press. And so I learned to think critically of issues, but also to think critically of history.

Monica grew up in Uvalde, Texas. It’s about ninety minutes west of San Antonio, towards the border. Today it’s known as the site of the deadliest school shooting in Texas history. But fourteen years before Monica was born, Uvalde was in the news because of a student protest.

Monica Muñoz Martinez: My mom shared a memory with me when I remember looking at photographs of the school walkout.

In the 1960s, Chicano activists—inspired by writers like Américo Paredes—had been organizing voters, and raising money to pay poll taxes, and supporting Mexican American candidates. Mexican American students in South Texas were staging protests against school segregation.

And then, in 1970, the school board in Uvalde fired a teacher named Josué Garza. He was a beloved figure for Mexican American students, but when he ran for county judge—part of this movement to claim Tejano political power—the district refused to renew his contract.

Students rallied around him. They delivered a list of demands, and as many as six hundred of them walked out of class and led marches. Monica’s mother was one of them.

Monica Muñoz Martinez: And you see elementary school kids and high school kids, and they’re in single-file lines. And I asked her, I said, “You know, why were you always walking in these, these lines?” And she explained that the Texas Rangers and the local law enforcement were threatening to arrest anybody who didn’t stay on the sidewalks.

Witnesses remember that two dozen Texas Rangers and two state police helicopters came to town.

Monica Muñoz Martinez: My parents, who were sophomores at the time, also knowing—they knew the history of brutality; they knew the history; they knew the recent history of some of the Texas Rangers that were there, like A. Y. Allee.

Alfred Young Allee was the captain of Rangers Company D. He had developed a troubled reputation in South Texas.

Monica Muñoz Martinez: It wasn’t only that he was an intimidating factor as a law enforcement officer, right—criminalizing, making these kids and these parents out to be some threat—but also that they had records of violence.

A reporter in the seventies called Allee “the last of the old-time Rangers.” He’d joined the force in 1931, and his grandfather, father, and son were all Rangers too.

Allee was a compelling figure for new Rangers—here’s how one of them, Jerome H. Preiss, remembered him:

Jerome Preiss: We, the Ranger company—Company D, at that time—was under the head of Captain A. Y. Allee: the great Texas Ranger Captain whom I had admired as a young man and hoped that if a vacancy was ever came up in the Rangers, that it could be under Captain Allee.

But by 1970, Allee was also notorious in South Texas, especially among Mexican Americans.

Announcer: Aquí están “Los Rinches de Tejas.”

And mostly for one incident: his response to a farmworkers’ strike on the border, in Starr County.

Singing “Los Rinches de Texas”: Voy a cantarles, señores, / De los pobres infortunios / De algo que sucedió / El día primero de junio.

It even inspired a new corrido, “Los Rinches de Texas”—sung here by Dueto Reynosa. It describes an “act of bloodshed” against those farmworkers.

Singing “Los Rinches de Texas”: En el condado de estrella / En el mérito Río Grande / Junio de sesenta y siete / Sucedió un hecho de sangre.

It also inspired a lawsuit, accusing Allee and his Rangers—and the local sheriff—of violence and arbitrary arrests. It went all the way to the Supreme Court.

Justice William O. Douglas: . . . On appeal from a three-judge district court in Texas. And the controversy arose in connection with the effort of the union to unionize farmworkers.

Ultimately, the case wound up giving more protections to labor organizers in Texas. And, at a federal civil rights hearing in San Antonio, people came forward, accusing Allee of slapping them and roughly grabbing them by the pants.

Allee was at that hearing. And as the audience booed him, he defended himself, saying it was the organizers who’d been “loud and abusive.” Elsewhere, Allee called the accusations, quote, “just a bunch of perjuries” and complained that “this civil rights” was “the doggonedest business I ever heard of.”

But he also later admitted to hitting an organizer—named Magdaleno Dimas—with the barrel of his shotgun. Dimas wound up hospitalized with a concussion and spinal damage.

This was the same Ranger captain who led the response to the student walkout in Uvalde. It was an unmistakable history lesson.

Monica Muñoz Martinez: I remember talking to my tía Olga Rodriguez, who recalled the memories of walking into the school buildings to meet with school board members and seeing Texas Rangers on the rooftops with rifles, you know, pointed down at them.

Jack Herrera: At high schoolers, basically. And parents—

Monica Muñoz Martinez: At high schoolers and parents, yes. Children, also elementary school children.

Many students kept quiet about the protests for years afterwards.

Monica Muñoz Martinez: But growing up, the history of the school walkout was something that people talked about in private: in their family homes, at family barbecues, at gatherings. But it was still a history that had not been actually publicly reckoned with. There was still a sense that, you know, the students who had walked out were troublemakers. And so the lessons that I learned about the past were, you know, that these calls for justice were unanswered. That they were continuing. But also that people who stood up and vocalized their concerns did so, and they made great sacrifices for it.

Like Texas itself, the Rangers have tried to move on from the violence of the twentieth century. But they still carry the same name and wear the same white hats of those Rangers of the past. For today’s Rangers, what’s changed, and what hasn’t?