Listen to this episode on Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher | Google. Read the transcript below.

Subscribe

When we ask what the Texas Rangers mean to Texas today, it gets to the heart of what we do with history. What do the people who came before us mean to us?

In the past decade, historians and descendants of victims of La Hora de Sangre have raised awareness of the violence against Mexican Americans in the 1910s—including with new historical markers placed by the State of Texas. But organizers of the Texas Rangers’ bicentennial in 2023 want to remind Texans of the virtues that made Rangers legends in the first place.

White Hats is produced and edited by Patrick Michels and produced and engineered by Brian Standefer, who also wrote the music. Additional production is by Isabella Van Trease and Claire McInerny. Additional editing is by Rafe Bartholomew. Our reporting team includes Mike Hall, Cat Cardenas, and Christian Wallace. Will Bostwick is our fact-checker. Artwork is by Emily Kimbro and Victoria Millner.

Album illustration by Edward Kinsella. Studio musicians were David Pulkingham, Michael Langoria, Daniel Durham, and Jan Flemming.

Archival tape in this episode is from NBC DFW, KXAN-TV, and Fox News.

Transcript

Jack Herrera (voice-over): In 2009, Monica Muñoz Martinez was in graduate school at Yale, when she got a package from back home in Texas.

It was from her uncle, Rogelio Muñoz. He was a lawyer and a civil rights leader in her hometown of Uvalde.

Monica Muñoz Martinez: He called me and asked me for my address in Connecticut, and saying, “I’m sending you a package.” I’m like, “Okay, great. What is it?” And, “you just check your mail.”

Jack Herrera: Do you remember what it looked like? It shows up . . .

Monica Muñoz Martinez: Yeah, it was like a, a legal manila envelope, you know, with the brass, you know, the little cord? The little string? . . . I mean, like, my parents would do things like mail me pan dulce. You know, “Is he sending me a treat?” No, it was a collection of records about the Porvenir massacre.

It was from Benita Albarado, the daughter of Juan Flores, the Porvenir survivor. She and her husband had been following the paper trails, and they had asked Monica’s uncle if he could represent them. He told them he didn’t practice that kind of law, but he sent them to Monica, an historian, to see if she could help.

Monica Muñoz Martinez: And they—here they were in, you know, 2009, still trying to see if there’s legal avenues for seeking justice for their loved ones.

The package had typed pages of notes taken by Albarado, and newspaper articles . . .

Monica Muñoz Martinez: I remember there were—they had photocopies of letters from James Monroe Fox. There were copies of Harry Warren’s list of the victims. And I remember laying them out, like opening it up, pulling it out, and, you know, reading it and just trying to make sense of the next steps.

And she wasn’t in a position to help the Albarados file a case in court . . .

Monica Muñoz Martinez: But that really launched the deeper questions about not just vigilante violence, but state-sanctioned violence, the roles of Texas Rangers, and these big questions about how a massacre like this could take place and the survivors could be denied justice.

Her book about this—called The Injustice Never Leaves You—came out in 2018. Monica is a public historian. And she felt a responsibility to reach as many people as she could, especially as the one-hundredth anniversary of the massacre got closer. The Albarado family told her they wanted the state to officially recognize what actually happened at Porvenir.

So, along with other historians and descendants, they applied to place a historical marker along a busy highway north of Porvenir.

And, at least at first, getting the state’s approval wasn’t a problem. An order went out to a foundry to produce the metal plaque. They set a date in September to unveil it. But as the date approached, they started getting resistance.

Monica Muñoz Martinez: And there was a pretty coordinated effort by local residents, by the local county historical commission and some local historians to try to stop the marker from being unveiled.

They faced opposition from some of the most powerful people in Presidio County.

A letter, obtained by the Texas Observer, showed that in late summer 2018, the Presidio County Attorney asked state officials to “temporarily rescind” their approval of the marker.

He said he had concerns about what the plaque would say, and about the ceremony where it would be unveiled.

This was a couple months after the Trump administration acknowledged that it had been separating migrant children from their parents after crossing the border. And some officials in this border county were worried this historical event might turn political.

Monica Muñoz Martinez: Yeah. I mean, the accusations that were made in the efforts to stop the historical marker, were just so outlandish that, you know, that the sponsor, quote-unquote, was like an operative for La Raza Unida Party, that Beto O’Rourke was gonna be there, that there actually might be a mob, you know, there might actually be violence at this event.

And there were deeper concerns—some local residents said the marker just shouldn’t exist. That, after all, they said, the people of Porvenir had been bandits.

Officials were just hoping to get through this without stirring up trouble. In an email, one state historical commissioner said, “This whole thing is a burning football that will be thrown to the media.”

The state finally did hold the ceremony in November that year, at the county courthouse in Marfa.

[National Anthem plays at Porvenir marker ceremony]

Officiant: For if the massacre at Porvenir is forgotten, the way will be paved for others, as we see today. This plaque is one step toward helping us to never forget, lest we learn nothing.

Descendants and local officials spoke, and the names of the victims were read out loud . . . acknowledged by the state, finally.

Woman: Longino Flores

Man: Antonio Castaneda

Woman: Pedro Herrera

Man: Viviano Herrera

Woman: Severiano Herrera . . .

But the last few months had shown . . . that one hundred years after Porvenir, this history remains unsettled. What we make of the Rangers, and their part in making Texas what it is—also says a lot about what kind of place we want Texas to be.

And, as the Rangers’ bicentennial gets underway, it’s about to be a big deal again.

From Texas Monthly, this is White Hats: a story of the legendary Texas Rangers and a struggle for the soul of Texas. I’m your host, Jack Herrera.

This is our sixth and final episode: “Memorials and Monuments.”

In 2023, the Rangers will mark their bicentennial. And, a quick history lesson here:

Byron Johnson: If you go to most books, what they’re going to tell you is the Texas Rangers were founded in 1823 by Steven F. Austin, and that’s not actually historically correct . . .

This is Byron Johnson, who heads the Texas Ranger Museum in Waco.

Byron Johnson: They were founded by a request of Austin to the Governor of Mexican Texas, José Trespalacios, to allow him to raise men for protection, something he was allowed to do, but he had to get permission from the Mexican government.

And, for the record—some people actually date the founding to 1835, which was the year the first Rangers were appointed by early Texan officials. But anyway, 2023 is going to be a big year for the Rangers and their supporters.

Byron told us that he and the museum are only consultants on the bicentennial plans. He’s offered suggestions on how to mark the history accurately, and respectfully.

Byron Johnson: We went to the state a few years ago and said, “We don’t want to see junk.” There are many aspects of it that probably should not be turned into air fresheners and things like that. . . . So, hopefully it will be done in a way that will be representative of what it ought to be. But you never know. We live in interesting times.

Jack Herrera: Doing the work of history is not a simple job.

Byron Johnson: No, dealing with history is not a simple job and it’s not something that should be used for political promotion. It really isn’t. It’s something that needs to be handled in a . . . What’s a good term for it? Neutral fashion?

It’s not the State of Texas, either, who’s raising money and planning these events. It’s all being done by a private group, called “Texas Ranger 2023.” Led by these folks . . .

Russell Molina: . . . Russell Molina, and I’m chairman of the Texas Ranger bicentennial coming up in 2023.

Lacy Finley: Hi, Jack. I’m Lacy Finley. I’m the executive director of Texas Ranger 2023, and executive director of the Texas Ranger Association Foundation.

Neither of them worked in law enforcement. And they’re not historians. I wanted to know why the Rangers were so important to them.

Lacy Finley: Well, it’s like with your own children, you teach them, or you try to teach them that, when you’re in a bind, you look for somebody in a uniform. But when you’re out in a rural community, and something really bad happens, you look for the man or the woman in the white hat. . . . They are there to help you and sort the situation out. And that’s something that’s taught to us generationally, really.

As for Russell, he says he grew up in a law enforcement family.

Russell Molina: Well, it really starts with my father. He was a justice of the peace in Fort Bend County, and then became the sheriff of Fort Bend County in the early nineties. And there was a family, the Leal family, who I grew up with. Tony Leal became a Ranger when my father became a sheriff.

As Russell grew up, he stayed in touch with Tony Leal, who went on to become captain of Company A, in Houston, and eventually head of the entire Ranger division. The first-ever Hispanic chief of the Texas Rangers.

It was Tony who first invited Russell to join the board of a foundation that supports Rangers and their families. For the bicentennial, Russell is taking that work to another level. They’ve been planning it for six years.

First comes a kickoff party in January, at the Fort Worth Stock Show and Rodeo, followed by events across Texas for the rest of the year: fishing and shooting tournaments, barbecue cookoffs, galas, and parades.

They’re hoping to raise 10 million dollars—to pay for all these events, but also for scholarships, financial assistance for Rangers and their families, a mobile history museum, and new Ranger statues at the headquarters in Austin.

Russell Molina: Well, we already have it actually designed, but it’s a 77-foot-circumference circle. . . . Anchored by the Texas star in the middle. And there will be a pedestal. The pedestal will be 2 feet high, and then the statue on top of that will be a bronze, 9 feet tall, that will have a DPS trooper with his hat over his heart, looking down at a leaning-over old gravestone, which is the first who died in the line of duty, and that’s the centerpiece.

Russell says this is a tribute to Moses Smith Hornsby, who was killed in 1835.

Russell Molina: And then around that circumference, there’ll be three monoliths. One has the state of Texas with hands underneath it holding up the state of Texas, and that represents all the administrative folks within DPS. And another monolith will have an old Ranger, his hand on the shoulder of a young DPS trooper, and the DPS trooper is pointing forward. So that’s the old, the past to the present, pointing to the future. And then the third showcases a male and a female DPS trooper with a canine along with a helicopter and plane showcasing the modern era of DPS.

In my head, I couldn’t help but compare this monument to the one that I’d almost driven past outside of Brownsville—the small marker commemorating La Matanza.

Jack Herrera: And so, one question I have, is—the bicentennial is a celebration. Like you said, it’s a chance to make people feel proud and drawn to this history. So how do you, in the context of a celebration, also have this very serious history that you’re being clear that it’s not being celebrated and not being covered up, it’s there.

Russell Molina: Well, so, one of the things we started early on was actually using the word “commemoration,” not “celebration,” because there are certain things you cannot celebrate in this, in that respect. So certainly you can’t celebrate certain things, but again, I think that that’s true with any organization that has any significant history at all. I mean, we could go through how do people still go to Catholic church after the situation there? Even our armed forces has incidents in their past that you can’t celebrate that, but you can certainly commemorate, and we wouldn’t be who we are, and we wouldn’t be the state of Texas, if it wasn’t for what occurred, again, the good, the bad and the ugly, to get to where we are today.

Russell says where they’re focused is on the Rangers who wear the star today. And who’ll wear the star tomorrow.

Russell is hoping that the Rangers’ legend can encourage young Texans to pursue careers in law enforcement. Right now, across the state, police departments are having trouble recruiting new officers. Austin PD, for instance, has hundreds of vacancies.

Russell Molina: Law enforcement obviously has been under strain here recently. So it’s something where we do need to have good men and women going into this profession.

One of the more obvious reasons why recruitment rates are down is because of the reckoning that followed George Floyd’s murder.

Around the country, communities have confronted the harm caused by abuse and racism in law enforcement. And that criticism has included the White Hats.

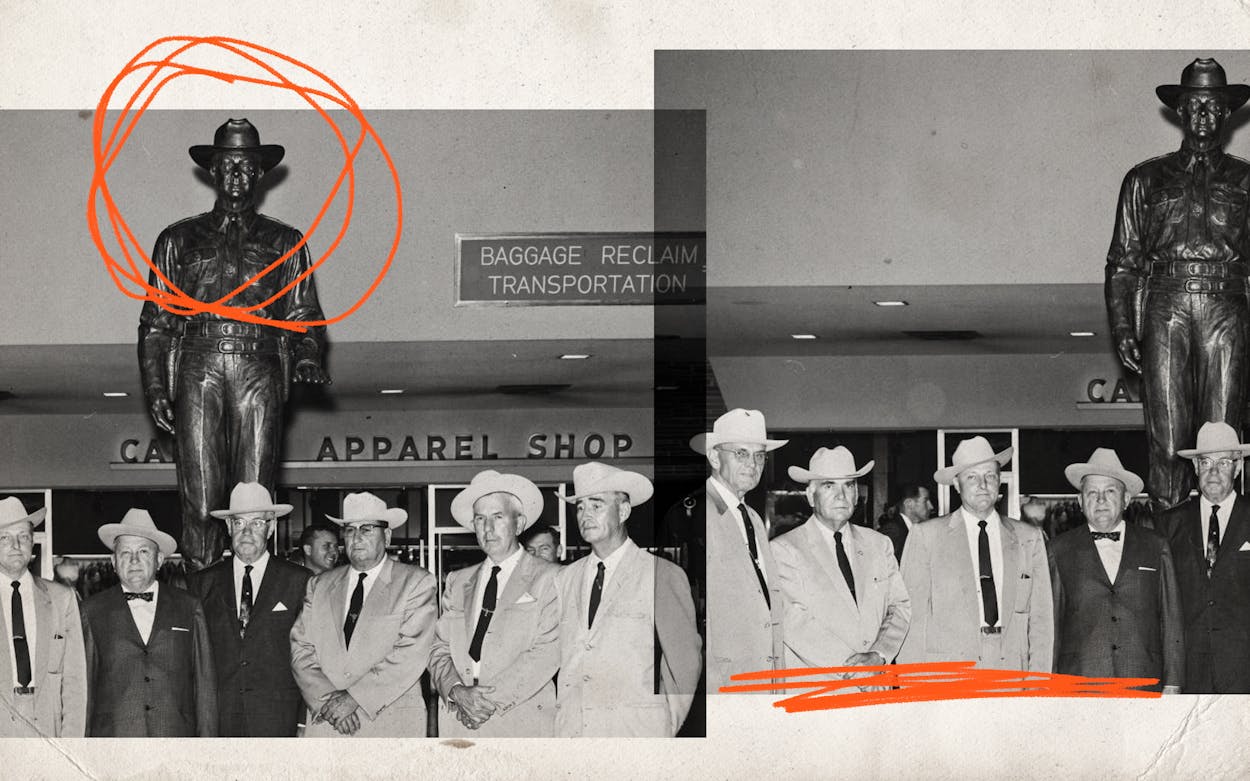

NBC DFW anchor Brian Curtis: A fixture at Dallas Love Field has been hauled away. Our partners at the Dallas Morning News captured the moment the iconic statue of a Texas Ranger was removed this morning.

In early June 2020, the City of Dallas removed a statue of the Texas Ranger captain Jay Banks. The twelve-foot statue had greeted travelers flying in and out of Love Field Airport since 1963. But it took just a few days to take it down.

George Floyd had been murdered by Minneapolis police just a week and a half earlier, and protests against racism and police brutality were spreading across the world.

And the June 2020 issue of D Magazine, on news racks around Dallas at the time, had an excerpt from a new book about the Rangers and their violent past. It was from Cult of Glory, by the journalist Doug Swanson. And it told the story of how Banks had been dispatched to a protest at Mansfield High School, near Fort Worth, in 1956. A white mob was protesting a court order that would force the segregated school to allow Black students.

Rather than enforce the order, Banks and his Rangers stood and watched. Some Rangers posed for photos with an effigy of a Black man hanging from a noose above the front doors.

In 2020, city officials took just a few days to decide the statue wasn’t worth keeping around.

It was a moment when people all over the country were reconsidering decades-old decisions about who gets recognized, and how to honor them.

For victims of the Porvenir massacre, throughout the twentieth century, the question wasn’t how to remember them—but if they’d be remembered at all. Before the last few years, the Porvenir massacre wasn’t widely known. So in 2014, Monica Muñoz Martinez, Trini Gonzales, Benjamin Johnson, and other historians formed a group to change that. They called it Refusing to Forget.

Here’s how Trini explained it to me:

Trinidad Gonzales: The reason it’s important today is not just simply to pay respect to our ancestors. It’s also to give us the moral compass to figure out how to make a better world today. And that compass cannot work if it’s skewed by mythology.

KXAN anchor Robert Hadlock: Today marks one hundred years since the Porvenir massacre in Texas. Hundreds turned out to the state capitol today to honor the lives that were lost. . . . On this day in 1918, a group of unarmed men and boys living in Presidio County in the Big Bend area were killed in the middle of the night.

In 2018, the Refusing to Forget group joined descendants like Arlinda Valencia for a commemoration of Porvenir at the state capitol. And they helped organize a conference at the state history museum just down the street, for the Canales investigation’s centennial.

They also got the State of Texas to place four new historical markers.

In their work to make this history more present, they made the State of Texas their partner.

Monica and Trini reminded me that during La Matanza, hysteria about Mexican raiders crossing the border created a culture of anti-Mexican violence. Today, we’re hearing similar language about people crossing the border from the state’s top officials.

Dan Patrick on Fox News: We cannot allow our country to be taken over by people who do not share our values, do not share our principles, don’t know our history, and really aren’t loyal to our flag.

Greg Abbott on Fox News: And so yes, we do have an invasion, driven by the cartels, coming across our border that are pouring people into our country at unprecedented levels.

Dan Patrick on Fox News: And if the federal government won’t enforce the law, then we need to enforce the law.

Monica has also seen history repeat itself—in her own hometown.

During the Robb Elementary shooting, almost 400 officers stood outside a classroom—some for more than an hour—doing nothing, with the gunman inside. Among them was at least one Ranger. In the aftermath, as families of the victims demanded answers about why the police response took so long, the Texas Rangers conducted the investigation.

And—infamously—DPS kept offering contradictory and false statements about what had happened after police arrived at the school.

Without much to go on, families were left to search for answers themselves. In late October, some of them spoke to the board that oversees DPS and the Rangers.

Manuel Rizo: We were told constantly to find closure in this. Well, closure to our families is not an option until we have the answers and hold those responsible accountable.

Jesse Rizo: But every single time, seemed like a lie after a lie, misinformation, roadblock after roadblock. And you can’t begin the healing process. Every single time that this comes up, it opens up the wound.

Commissioner: I’m now gonna call on Dr. Monica Martinez, who’s also gonna speak on Uvalde.

Monica Muñoz Martinez: Good morning, commissioners. Thank you for allowing me to speak today.

Monica told them there were lessons they could learn from history, if they were willing to listen.

Monica Muñoz Martinez: My research into lynchings and massacres one hundred years ago could not have prepared me for the horrors of the Uvalde massacre, and the cruelty months after the massacre.

And she recounted the stories of Jesus Bazán, Antonio Longoria, and Porvenir.

Monica Muñoz Martinez: Families in Uvalde should not have anything in common with the victims that survived the massacres of one hundred years ago. Unfortunately, they do. Painfully, they do. They are bearing the burden of having to call for justice, pleading for transparency and accountability after surviving the horrors of the Uvalde massacre.

When the first trailer for our podcast came out, I got a message from Russell Molina. It was a long email, which actually included footnotes, arguing that we were at risk of getting facts about the Rangers wrong. Russell told me: “We will be ready to fully tell the story so that . . . history can be looked at in full context.” I decided to get on the phone with him as soon as I could.

Russell Molina: Well, yeah, so I think that it was just simply, there were some things in there that you, you pointed out that have, that full context needs to be put to those words, right.

Russell went through the facts he wanted to make sure we understood: He told me when old stories talk about “los rinches,” sometimes that refers to other law enforcement, not Texas Rangers. Another was that many of the Rangers who committed atrocities during La Matanza had special Ranger appointments, not standard ones.

Russell Molina: Well, they’re really separate entities, right? There are other acts that occurred by “special Rangers,” “loyalty Rangers,” these others that would not be what we—we being the Texas Ranger Bicentennial celebr—or trying to commemorate the 200 years of history—that we would say, that’s not our history.

But it was obvious that something bigger bothered him about the way we had framed our show. We had made the decision to focus on La Matanza, on extrajudicial executions during the 1910s, on Porvenir. Russell said that was worthwhile to talk about. But—

Russell Molina: I also think that you have to look at the good, there’s good that the Rangers have done prior to, post that, even during that. So that’s the other piece that seems to get lost, is everybody wants to look at the destruction aspect of it. Well, let’s look at the building part of it. Let’s look at that positive piece as well, because there was good that was done.

Russell said it frustrates him that some people want to focus entirely on the Rangers’ negative history. And by “some people,” I think he also meant me.

Russell Molina: Well, I’ll tell you, it’s simply the fact that there’s more to the story than the myopic cherry-picking that I think that has been done in regards to what they are about and what they have done. And if you really look at the number of incidents that you can actually put down on paper to say, okay, here’s the good, here’s the bad, and here’s the ugly, the good so far outweighs the other two.

Russell is Latino as well, with family roots in South Texas, and I asked him for his advice about how he’s gotten his head around the violence Rangers committed against people like our ancestors.

Russell Molina: I would say talk to some of these Hispanic—you could talk to Tony Leal, the first Hispanic chief.

So on a rainy day just before Thanksgiving, I made the drive out to Houston to do just that.

Tony Leal—the first-ever Hispanic chief of the Texas Rangers—is the head of a private security company today. But as he welcomed me into his office, I could tell that he’s still a Ranger at heart. On his coat rack, there are two white cowboy hats—and that’s in addition to the four white hats in a glass case next to his desk. On top of a safe, he’s got a pair of leather cowboy boots embossed with the Ranger star.

For the better part of a year, I’ve been trying to figure out where Mexican Americans fit into the Ranger legacy. That was a question Tony had to answer every day that he put on that white hat. He shows me a photo of the badge he wore as a Ranger captain.

Tony Leal: So that one? That’s a captain’s badge. So it’s actually made out of a 50 peso.

Jack Herrera: 50-peso coin.

Tony Leal: Solid gold.

It’s a Ranger tradition—taking a Mexican coin and hammering out the Texas star.

In Tony’s office, wood-paneled walls are covered with photos of him with other Rangers, as well as a series of letters and proclamations.

Our first few episodes of this podcast were already out by this point, and I knew that Tony understood we were taking a critical perspective on the Rangers. But when we started talking it felt sort of like I was talking to one of my uncles. Early on, we realized we did have similar family histories.

Tony Leal: So my family, the first traces of our name on the Texas side of the border are late 1600s, early 1700s, in Webb County.

Jack Herrera: So around the Laredo area?

Tony Leal: Yeah.

Each of us also had Mexican ancestors who’d joined the Confederate Army.

Tony Leal: So you think about that, we’re Hispanic, and you usually don’t grow up thinking that you fought in a war.

Jack Herrera: The Civil War.

Tony Leal: Trying to maintain slavery. But our people did.

Jack Herrera: That changed the way I thought about myself when I found out about that.

Tony Leal: I did too. I had to sit back because it was one of those things my wife always knew, because they were from the Mayflower. And she looked at, “Oh my God, we had plantation owners in my family.” Yes, you did. But it’s not something I ever considered because we’ve always been told that Mexico was against slavery. But we did have some Tejanos that were trying to assimilate also and were required if they were going to be landowners to join the army.

Tony grew up in Sugar Land, Texas, out by Houston. But he says his identity is most shaped by his family’s deep roots in the Rio Grande Valley, where his uncles live to this day.

Tony Leal: That’s the part of my childhood I remember because as soon as we were off for Christmas vacation, pa’ el valle. As soon as we were off for Thanksgiving vacation, pa’ el valle.

I asked him if he ever heard stories about the Rangers there, or about los Rinches, the way someone like Trini Gonzales did.

Tony Leal: You know, I would hear stories from, just a kid, hearing, would say, “Oh yeah, that’s when your great-uncle Juan Fernin killed that ranger down there in that shootout.” So I would hear that mutual combat kind of story, but I never heard a story of, like, “Hey, the rangers kicked into a door and killed six innocent people.”

Sugar Land is a town that was built around farms that relied on prison labor, and when Tony was young there was still a prison farm in town. If men escaped, the Rangers would show up. That’s Tony’s first recollection of them.

Tony Leal: You’d see them come down the dirt road with the dirt behind the highway patrol cars and the Rangers in their cars. And then they would all be standing somewhere talking with the warden and all that. To me, it was like, “I don’t know what they’re talking about, but one of these days I want to know what they’re talking about.”

In the early twentieth century, pretty much every cop in Texas was Anglo. But by the time Tony was a teenager, things were changing, especially in the Valley.

Tony Leal: By the time I was growing up, when you met the sheriff, you know, Pérez, he was Hispanic. When you met the Chief of Police of McAllen, he was Hispanic. When you met the Chief of Police or Sheriff in Brownsville, he was Hispanic.

Tony says he was part of the first generation of Latinos in Texas who could actually dream about growing up and joining law enforcement. And he set his sights on the State Highway Patrol. He went to school, took the training, and he was eventually stationed in San Antonio.

Tony Leal: And I just happened to be across the hallway from the Ranger office and the Ranger captain at that time was a guy named Jack Dean. He looked like John Wayne, like a Hollywood . . . If you said, “What does a Ranger captain look like?” Six-foot-four, 50-year-old, gray-headed, looked like a Ranger captain. But the Rangers in there were Al Cuellar, Rudy Rodriguez, and Ray Martinez.

Tony ended up getting close with these three Rangers—they went out to lunch and took smoke breaks together.

Tony Leal: I had never met Hispanic Rangers before, and there was three of them. Right across the deal from me.

In 1993, one of the Rangers needed backup to nab a kidnapping suspect.

Tony Leal: So Al Cuellar, who’s Hispanic, he says, “Hey, that little Mexican highway patrol sergeant is pretty sharp. Can I use him?”

This turned out to be Tony’s big break. When they arrested the kidnapper, the captain took notice.

Tony Leal: Jack Dean walked by my office and he knocked on the window like that and I looked up and he says, “You might want to think about taking the Ranger test next month.”

Tony applied, and when he was accepted to the force, he became the youngest Ranger in modern history.

Tony says that during his time as a Ranger there were a few times he took flak from other Hispanics for his career choice. But much more often, the response was positive.

Tony Leal: I remember speaking before the Senate in McAllen where the community was there, and been about ’08, ’09, and just people that would just come up and shake your hand, un señor mayor, una señora mayor. And they would just come shake your hand and say, “I’m so proud of you and I’m so proud to see a Hispanic leading the Rangers.”

And he knew his dad was proud of him too, but he could tell he felt some sort of reservation.

Tony Leal: When my father was growing up. When my father came back in the early fifties from being a United States Marine, he couldn’t have gone to work for DPS. They wouldn’t take your application. . . . I don’t think my father accepted that I was a Ranger until I made captain. I think my father finally accepted that a Mexicano, Hispano, Tejano, whatever you want to call it, could rise to that rank within the Texas Rangers.

Tony had an impressive career. During his years as a Ranger, he solved an eleven-year-old cold case, investigated an ambush on police officers, and solved multiple murders. I had come with questions about his professional history—but Tony said he doesn’t like to talk about all that.

Tony Leal: And I’ve got a lot of big cases. But for me, I deal with it by moving on from it. So when people ask me, “Can you tell me big cases you worked?” I choose not to go back to there. I choose not to. I can smell it. If I think about the case, I can smell it.

Tony moves on by moving on.

In 2008, Tony became the chief of the entire Ranger force—the first Hispanic person to ever hold that job.

Jack Herrera: What are you thinking about? What are you feeling? What does that moment mean to you?

Tony Leal: I don’t know that other than all the calls from media, I’ve never—I don’t know about you—I’ve never thought of myself as a Hispanic Ranger. And I had never thought of myself as a Hispanic Highway Patrolman. But there was no gravity in it to me that said, “Hey, I am the first Hispanic chief.” . . . .

I think that we’ve got to get race sometimes away from what we’re doing because if we don’t, we ourselves are perpetuating that there’s a difference when there shouldn’t be.

Tony might not have liked thinking in terms of race when it comes to police work, but it was hard not to when he became Ranger chief. The force then—as it remains today—was overwhelmingly white and overwhelmingly male. Tony says he worked to build a more welcoming image for female and Black Rangers especially.

He told me that even just the look of the white hats could alienate potential Rangers, who didn’t identify with the “cowboy look.” Tony didn’t do anything to change the uniform. But in some places, he found a way to use it as an opportunity.

Tony Leal: When I was a ranger in Seguin, my wife taught elementary school there, and I was asked several times by, “Come speak at the school, career day.” And Seguin, Guadalupe County, Gonzales, big cowboy area. And I would see the Anglo kids with Wranglers and boots and all that. And I would tell the Hispanic kids, I would tell them, I said, “Hey, look, you don’t understand, this cowboy thing is your culture, it’s not their culture. Your culture taught them this culture, every word they have comes from your language—rodeo, rodeo, a lasso, lazo, chaparreras, chaps, you know, are the cowboy culture. You are the ones that taught people how to work cattle, that taught them how to break horses, that taught them how to train horses.”

There’s something else that early Mexican culture in this state gave to Texans: Rangers. Before Stephen F. Austin and the first Anglos arrived in this state, Mexican compañías volantes were mounted troops who rode fast and light, patrolling vast territory and waging war on Native people.

For Tony, this is part of his pride in being a Texas Ranger. It’s not that he’s a Latino who managed to take part in Anglo tradition. Instead, he sees the Rangers as his own heritage. Tejano heritage. Today, it bothers Tony that the Mexican, Tejano history of the Rangers—and of Texas—isn’t told. He thinks if we told the whole story, Mexican Texans might feel less alienated from the Rangers.

And a few years ago, doing his own family’s genealogy, Tony learned that Rangers are literally part of his heritage.

Tony Leal: I have studied this stuff on my side of the family. And one of my second-great-grandfather from Webb County served in the Ranger Battalion. I mean, I’ve got where he signed his name.

I’ve studied my family’s history too. And my Mexican ancestors also fought against Native people, and for the cause of slavery. Today, Tony and I both have to find a way to live with that.

Tony Leal: I think we all do. Every single person. . . . I’ve struggled on several things. I’ve struggled about being Catholic because there’s some things that Catholic churches under there are just crazy to think about. . . . I think it’d be easier to walk away from the Catholic church than to come to terms with those things. We have to admit that the institution that we love has flaws, and it has flaws and did things that you can’t imagine.

Jack Herrera: And you’ve had to do that as a Ranger too, I imagine.

Tony Leal: Yeah. As a policeman, as a Ranger.

Jack Herrera: How about when you were actually on the force? Is this something that you thought about? Is this the history that you knew about or people talked about or other rangers talked about?

Tony Leal: No.

During his Ranger days, Tony didn’t know about the Porvenir massacre, or know all the details of what happened during La Matanza. But these days, he’s a student of Texas history. And it’s something he’s thought about more in recent years.

Tony Leal: The thing about the Rangers is this: it’s iconic. All right? If you want to be iconic and if you want to be known for wearing the white hats, you got to take responsibility, whether it’s now or then for the bad things. . . .

And I’m not saying that that kind of shit didn’t happen. I know it did. I know it happened on both sides. I know Rangers were ambushed by bandits. I know bandits and some innocent people were killed by Rangers. I know that happened. In our society, I know right now there’s bad cops that have killed innocent people. I know that there’s good cops that have been killed by bad people, ambushed. It’s still happening in 2022, but I don’t see how we can base what we’re feeling in 2022 about something that happened in 1915. We’ve got failures going on right now. We have law enforcement that failed in Uvalde. We’ve got things that we need to be worried about right now. So I don’t see why we do this. I don’t know why we’re trying to pick apart something that happened in 1915 instead of doing a whole podcast on what are the Rangers doing in 2022.

At one point, Tony said something I didn’t expect:

Jack Herrera: I say this in the show, actually, it’ll come in later. I think it’d be very silly to ask the modern Rangers to stand responsible or be held to account for what happened in 1915.

Tony Leal: I wouldn’t be held to account, but I would be—right now, I’m a former chief of the Texas Rangers.

Jack Herrera: Mm-hmm.

Tony Leal: And I would apologize right now. I apologize for anything that the Texas Rangers as an entity did unjustly. For me, it’s like the Rangers have moved on, the state has moved on. And let’s move on.

It’s that second part I’m still thinking about. Is it as simple as that? Can we move on?

When I was fourteen or fifteen, I spent a summer battling my first bad bout with insomnia. It was the first time I’d ever seen “5 a.m.” on the clock. At a certain point, I learned to just give up trying to sleep, and I’d go read or watch TV. That’s what I was doing one December in my grandparents’ house in San Antonio. It was about 4:30 a.m., and I was on the couch with a book when my grandpa Guillermo came downstairs, ready to start his day. He saw me on the couch and said, “Good, you’re up.”

He turned around and came back a second later with an imposing old briefcase. It was the same gray briefcase he’d taken to his office at NASA, where he’d been a chemist.

He waved at me to sit down with him at the kitchen table, and he began pulling out photos and old documents. I saw the arched cursive of the 1800s; a sepia-toned photo of old family members in Laredo. A newspaper headline from 1935 recorded the death of a “Jesús Herrera,” at age 94. The story said my great-great-grandfather Jesús was one of the last veterans of the Confederacy to die in Laredo.

Then my grandfather began telling me stories. He told me about how our family helped establish Nuevo Laredo, the city across the river from Laredo; how my ancestor Maria had been born in Laredo in 1802 and had lived under the Spanish, Mexican, Texan, American, and Confederate flag—without ever moving. And he told me that one of our ancestors was one of the first Mexican Texas Rangers. Then he told me stories of the gunfights that Ranger ancestor got in.

I remember when I got back to school in California, I told all my classmates that my ancestor had been a Texas Ranger. It was something that thrilled me.

When my grandfather Guillermo died in 2020, I inherited that old briefcase. And many times in the last few years, I’ve gone through it, adding my own research on the family’s genealogy. I’m the custodian of that history now.

I’ve found Catholic church records of my ancestors in Laredo, and their names appear on a census ordered by Texas president Mirabeau Lamar. I’ve got a letter from the adjutant general of the United States, declaring that Jesús Herrera was a veteran of the Confederacy, in the 33rd Battalion. It turns out that most of the stories my grandpa told me were true. I can prove them.

But I haven’t been able to find evidence that one of my ancestors was a Texas Ranger. I’m left to wonder if that’s a bit of family lore my grandfather wanted to believe, but could never prove.

The closest thing to evidence I’ve found is a line in Jesús’s obituary that says he was, quote, “an Indian fighter,” around Laredo. Maybe that meant some kind of Ranger.

I’ve always been fascinated by this ancestor, Jesús. What I feel . . . isn’t pride. That same obituary recorded that he fought for his “beloved Southland” in the Civil War. I’m ashamed that an Herrera fought on the side of slavery. Whatever kind of Indian fighter he was, I’m ashamed he raised a gun against Native people living on their own lands. And if he really was a Texas Ranger—well, today I feel complicated thinking about that.

Besides stories, my grandfather left me with a bit of wisdom that day. He said that some members of our family were hoping that our genealogy would connect us to Spanish nobles or important figures in Texas history. My grandfather said that didn’t matter to him. “It doesn’t matter to me if they were horse thieves,” he said. “I just want to know who they were.”

When we ask what the Texas Rangers, with all their history, mean to Texas today, it gets to the heart of what we do with history. What do the people who came before us mean to us?

I think, in that briefcase, Guillermo left me some instructions: That we shouldn’t go into our history searching for something to be proud of. We should go into our history searching for something to learn from.