In explaining how no one person in the Legislature deserves credit for passage of the big school finance and property tax plan this year, Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick inadvertently summed up the problem we at Texas Monthly had in choosing the Best and Worst Legislators: “This was a session of no individual standing out or standing up.”

If every legislative session has its own personality, its own flavor, then the 86th Legislature of 2019 was less juicy brisket and more rice cake—dull, tasteless, and allegedly good for you. Sure, lawmakers reformed the way public schools are financed while reining in the growth of property taxes, but it was perhaps less filling than advertised. Because lawmakers paid for the $11.5 billion package with a current budget surplus, they will have to find new funds again in the next legislative session. The whole thing could unravel if the economy goes south.

A normal legislative session is a three-tiered cake. At the top, there’s a banner issue set by leadership—ranging from heavyweight budget packages to pot-stirring items like where transgender teenagers can pee. In the next tier down are secondary, but still major issues such as reform of the child welfare system or highway construction, legislation that often takes several committees and multiple bills to pass. This is often where individual legislators can make a name for themselves. At the bottom tier lies everything else—technocratic matters, mini-crusades, district-specific issues, and vendor bills. In this session, school finance reform and cutting property taxes dominated the top of the pyramid, and there was plenty of minor stuff, but almost nothing in the middle. That means fewer legislators got to slime or shine.

This Legislature was also greatly influenced by political anxiety. The fact that Democrats picked up a dozen seats in the House in 2018 frightened the hell out of the Republicans. To undermine Democrats in 2020, Republican leaders spent a lot of political capital forcing votes on largely symbolic but potent wedge issues: The born-alive abortion bill. A proposed constitutional amendment against ever adopting an income tax. “Saving” Chick-fil-A. Ultimately, these third-tier maneuvers were about positioning the Republicans for the 2020 election, because whichever party is in charge of the 87th Legislature will control the legislative and congressional redistricting scheduled for 2021—and presumably dominate our politics through the next census in 2030.

All of this combined to make for a fairly lackluster legislative session.

We try to be nonpartisan when we choose the Best and Worst. For Best, we choose those legislators who worked in the public interest, particularly if they did so under difficult circumstances or out of the limelight. The venal, self-serving, or hateful comprise the Worst. We assemble our list by observation and by interviewing advocates, lobbyists, citizens, our fellow journalists, and the legislators themselves. This year, we took extra consideration to avoid the trap of only listening to, or thinking like, insiders. We hope our list is meaningful not just to those who toil under the Pink Dome, but to the millions of Texans with an interest in their state government.

This year, the two members on nearly everyone’s Best list were Speaker Dennis Bonnen and Representative Joe Moody for their ability to create an unusual level of harmony and bipartisanship in the House. Close to universal for Worst was Patrick, who is widely regarded as a hindrance to anything that doesn’t fit within his narrow, small-minded agenda. A persistent rumor—which he denied—that he was about to take a job in the Trump administration led more than one lobbyist to tell us that they were hoping and praying that Lieutenant Dan would soon be gone from the Capitol for good.

Governor Greg Abbott remained a cipher. In contrast to a string of dynamic governors going back to the seventies, whose priorities were writ large, Abbott’s agenda, as well as his legacy, is still unclear. Perhaps he wants to be the governor who sorta, kinda cut taxes? But unlike the two previous sessions, at least he was engaged this time. He deserves credit for helping get the school finance and property tax package across the finish line. As such, we are bestowing him with a new designation, Most Improved.

In a legislative session where the leadership was determined to keep conservative culture war issues from hijacking a mainstream agenda, individual achievement was difficult to discern. In choosing the Best legislators this year, we received recommendations to put the state’s budget writers—Senator Jane Nelson and Representative John Zerwas—on the Best list. But when you’ve got a $9 billion budget surplus plus $15 billion in the Rainy Day Fund, how hard is it to spend a windfall that makes Mega Millions look like a prize in a cereal box?

State senator Dawn Buckingham received cheers in the Senate when she passed the beer-to-go law, but is liberating booze Best-worthy? Senator Kel Seliger delivered an impassioned speech against Patrick’s tyranny, but then surrendered to him the procedural vote needed to move one of the lite guv’s property tax bill. And the Senate’s Democratic members mostly continued to act like Eeyore at his birthday party: “Oh, woe, there’s nothing we can do.”

Over in newbie Speaker Dennis Bonnen’s mostly sedated House, perennial troublemaker Jonathan Stickland promised to mature as a legislator, but nonetheless proved correct one of his Republican colleagues, who told the Dallas Morning News, “No one has talked more and done less.” Rather than honor him with a “Worst” designation, we created a new category for him this year: Cockroach.

Even in such a largely unmemorable legislative session, we at Texas Monthly are determined to put a spotlight on the Best of the best and hold up to scrutiny the Worst of the rest. So here is our report for 2019.

The Best

- House Speaker Dennis Bonnen

- Representative Joe Moody

- Representative James White

- Representative Donna Howard

- Representative Dade Phelan

- Representative Victoria Neave

- Senator Kirk Watson

- Representative Tom Oliverson

The Worst

- Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick

- Representative Tom Craddick

- Senator Bryan Hughes

- Representative Poncho Nevárez

- Senator Angela Paxton

- Representative Jeff Leach

- Senator John Whitmire

- Senator Brandon Creighton

Special Awards

- Most Improved: Governor Greg Abbott

- Cockroach: Representative Jonathan Stickland

- Freshman of the Year: Representative Julie Johnson

- Bull of the Brazos: Senator Paul Bettencourt

- Furniture

The Best

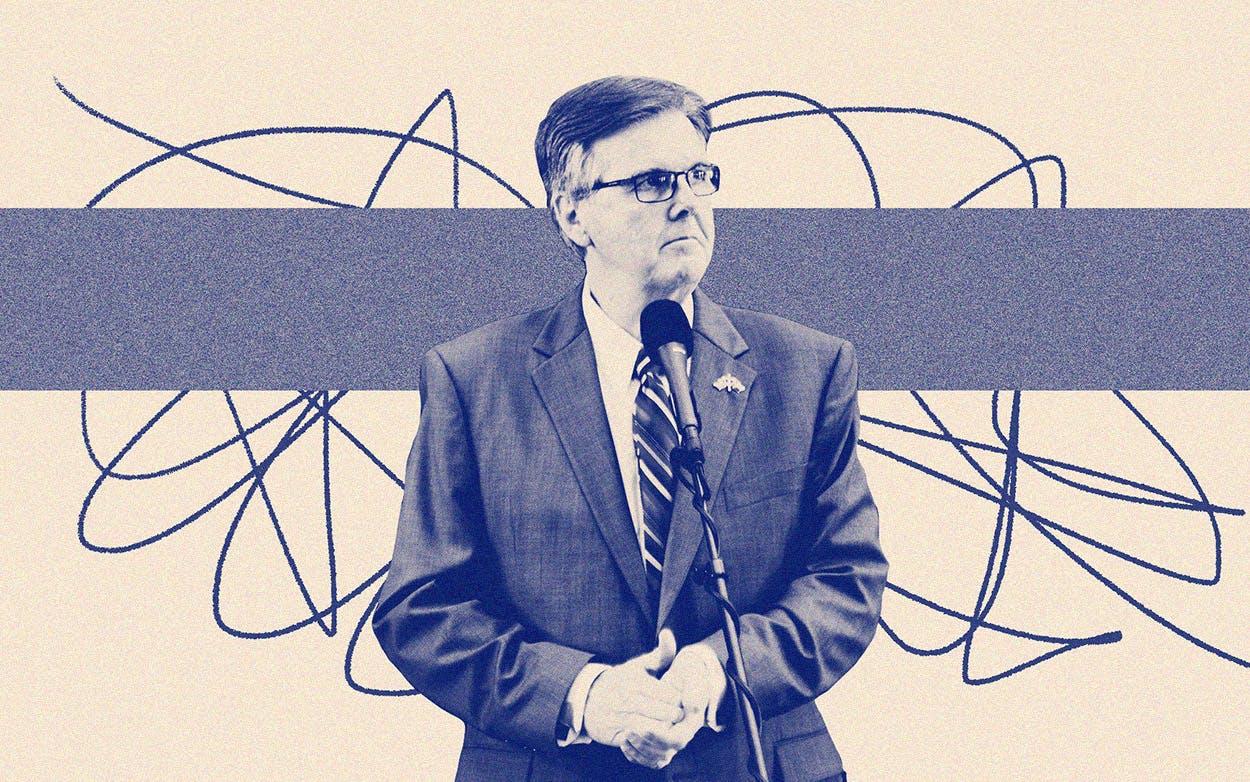

House Speaker Dennis Bonnen

R-Angleton

George Washington was famously purported to have said that the U.S. Senate was the saucer that cooled the hot coffee brewed up by the rambunctious and populist House. In Texas, at least in recent times, a new metaphor is needed: The Texas Senate partakes of an endless supply of high-grade trucker pep pills, but only manages to get the House to swallow a few.

The state should be thankful that new House Speaker Dennis Bonnen managed to keep alive the noble tradition of restraint. Texas has traditionally seen two kinds of House speakers: those who tell the chamber what to do, like former speaker Tom Craddick, and those who largely let the members figure it out among themselves, like former speaker Pete Laney, the last Democrat to hold the gavel. Bonnen garnered comparisons to Laney, who frequently told members to “vote your district.”

Laney was speaker when Bonnen did his first tour of duty in the House as a sergeant at arms in 1993, while he was still in college. First elected to the House in 1996, Bonnen is relatively young at 47, but he’s also one of only six Republicans who’ve served long enough to remember what it was like to be in the minority.

Like his predecessor, Joe Straus, Bonnen kept Democrats in the loop this session, continuing to parcel out powerful committee chairmanships to Democrats. He went even further in one respect, wisely deciding to make El Paso Democrat Joe Moody speaker pro tem, the position Bonnen held under Straus. That was an early sign that the House would continue to eschew the partisanship and extremism of the Senate.

When things started getting ugly late in the session (predictably over an anti–Planned Parenthood bill emanating from the Senate), Bonnen cut a deal with Democrats to deflect the rest of the Senate’s hand grenades—among them an effort to protect Confederate monuments and a retrograde elections bill.

For those with long memories, it’s hard to believe this is the same Dennis Bonnen who earned the moniker “Dennis the Menace” for his temper tantrums as a committee chair, and served for years as one of Straus’s top enforcers. When he won a spot on the Worst list back in 2011, we described him as a man who “drifted petulantly through the chamber.” This year he floated above it, and Bonnen mostly showed good spirits and goodwill in public. Mostly. His colleagues reported flashes of Bonnen’s trademark ire in his stewardship of the session’s big tax bill.

But his biggest blowup, against gun-rights activists who had been visiting lawmakers’ homes while they were in Austin, won him praise from members, because he was seen to be standing up for his colleagues.

Some in the House joked that Bonnen’s brother, Greg, a doctor and fellow state representative, must be medicating him. That happy buzz may wear off in time, but as of the end of this session, Bonnen, who started soaking up the traditions of the House more than a quarter-century ago, has risen to the occasion.

Back to List ⤒

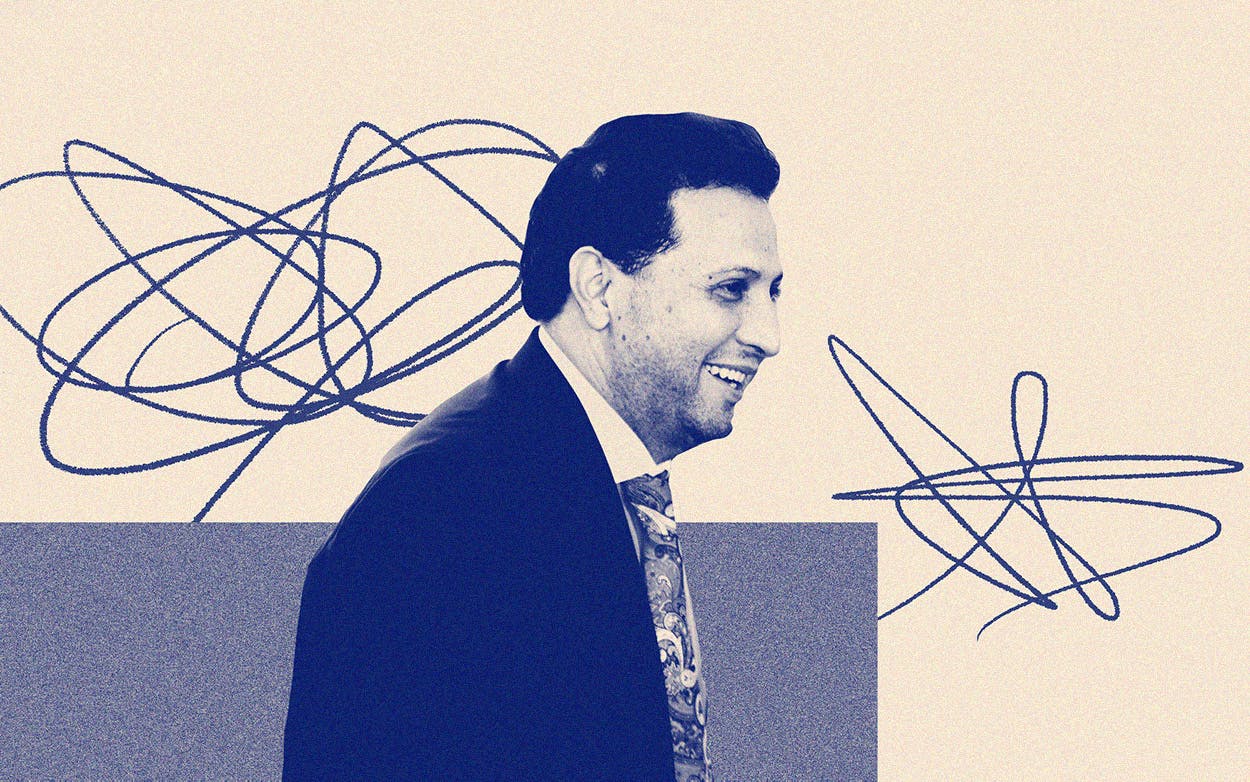

Representative Joe Moody

D-El Paso

What do you do if your colleague is brazenly trying to engineer a power grab on behalf of a member of his own church, a man who also happens to be the Texas attorney general? If you are Representative Joe Moody, you use the trust and goodwill of your fellow House members to stop the thing in its tracks.

The bill in question would have given Attorney General Ken Paxton sweeping new powers to take on human-trafficking cases, which it is questionably well-prepared to do—undermining local DAs in the process. Its sponsor in the House, Jeff Leach, is one of the Legislature’s most outspoken conservatives and a Paxton ally. Both men attend Prestonwood Baptist, a hub of evangelical politics in North Texas.

Given Leach’s and Paxton’s prominence, the proposal should have been a slam dunk in the Republican-controlled Legislature. But Moody, a former prosecutor and defense attorney, calmly dismantled the case for giving Paxton new prosecutorial powers. Moody argued that any good defense attorney could immediately subpoena local prosecutors to ask why they decided not to pursue a case. He also noted that two-thirds of the human-trafficking victims Leach kept citing as the reason for the legislation entailed labor violations that the attorney general has never bothered to pursue.

Leach preposterously charged that the debate over jurisdiction was callous to the needs of human-trafficking victims. But Moody stuck to the facts. When he offered an amendment that effectively gutted Leach’s bill, it was clear whose side the members were on—it passed and Leach conceded defeat. That’s just one reason Joe Moody is among the best legislators for the second session in a row.

When Moody speaks, people listen. Over the course of the session, he has used his perch as speaker pro tem and his reputation for honesty and smarts to shape policy and give voice to worthwhile causes that might otherwise have gone unheard. (Perhaps his affinity for hip-hop neckties—Tupac and Biggie among them—helps lighten the mood when he’s buttonholing a colleague over the finer points of policy.)

In just the last month of the session, Moody passed a bill making possession of small amounts of marijuana a ticketable offense by a more than 2-to-1 margin; single-handedly resurrected an ill-fated effort to limit arrests for Class C misdemeanors over furious opposition; and found the time to deliver the most effective and clear cross-examination at the hearing into the Department of Public Safety’s decision not to release relevant information about Sandra Bland’s death. Sometimes Moody won the battle and lost the war. But even when he did, he helped build bipartisan political pressure that increases the likelihood of winning next time.

At the end of the session, House Speaker Dennis Bonnen told the Austin American-Statesman that “Texas would be very blessed” to have Moody as speaker should the Democrats take the House in 2020. Amen.

Back to List ⤒

Representative James White

R-Hillister

James White is a man in a pressure cooker. He’s a rock-ribbed conservative in good standing with the right, a former Army officer who represents a mostly white district in deep East Texas. He’s also the only black Republican in the Legislature and one of his party’s leading advocates for criminal justice reform.

White often finds himself caught between competing types of distrust, whether it’s Democrats who question his motives or Republicans who don’t share his view of the world. At times, he seems like a contradiction, a man without a home. But White, the chair of the House Committee on Corrections, nonetheless helped pass a number of vitally needed reforms to the juvenile and adult prison systems. Colleagues from both parties said White succeeded because of the credibility he has accumulated over the years.

He was not afraid to take on hard sells. Exhibit A: his effort to limit arrests for minor offenses like traffic violations—a sensible change that was nonetheless vehemently opposed by powerful police unions. He told others that his willingness to tackle the issue was influenced by his own family’s experiences, including the fact that in 1950 his grandfather, a World War II vet, was shot to death by a special deputy constable in Houston after the man rear-ended his vehicle. White explained to the House floor that, in these times, he feared that one day his wife could find herself in the position of Sandra Bland, the woman who was arrested in 2015 during a traffic stop in Prairie View and later died in the Waller County jail.

Unfortunately, White’s effort to update the Sandra Bland Act by limiting misdemeanor arrests collapsed, largely thanks to a bizarre intercession from Democrats, who turned on the bill. When that happened, and at other times when White’s efforts were stymied, he showed understandable flashes of anger. “He can be a little volatile,” said one criminal justice reform advocate, describing the frustration White exhibited dealing with sometimes implacable opponents. “He’s always polite. He’s always got a beautiful bow tie. He’s leaning into people and trying to get them to understand. But every so often the wave of stupid just kind of hits him.”

But his ability to speak to different audiences—even when they were unsure what to make of him—was a key reason why the criminal justice reform movement didn’t have a complete flop this session. After the Sandra Bland bill failed, White told the Texas Observer that he was far from giving up. “I don’t know if it’s going to get done this session, but it’s going to get done,” he said.

Back to List ⤒

Representative Donna Howard

D-Austin

Some lawmakers serve as the conscience of the Legislature, passionately speaking out on issues. Others put aside partisanship to work hard with members of the other political party for the betterment of Texas. And some serve with determination in the face of personal tragedy. This session, Representative Donna Howard of Austin accomplished all three.

Eyeglasses frequently perched on her nose, she made the case for sensible policies with both passion and reason. One Republican lobbyist nominated Howard, a liberal Democrat from Austin, for the Best list, saying, “Donna Howard picks her partisan fights and then works across the aisle to get things done.” We have to agree.

Howard’s biggest moment this session was her dramatic speech against one of the most toxic, divisive bills to come up for debate. House Bill 16 will require doctors to provide medical care for a fetus that had somehow survived an abortion. Howard came to the House prepared for debate and noted that there’s no record of a single “born-alive” abortion ever occurring in Texas. “The aim of HB 16 is clear: further stigmatize abortion, misinform the public, intimidate physicians, and interfere with a woman’s ability to seek medical care,” Howard said. “We refuse to waste limited time we have here by entertaining malicious and purely political attacks against women and doctors.”

But Howard wasn’t just eloquent. She was tactical, too, encouraging Democrats to vote “present,” rather than “no,” on the bill. Without the votes to stop the legislation, why give opponents ammunition to accuse Democrats of supporting infanticide in a future election campaign?

Howard also knows how to build consensus. With two Republicans as coauthors, she managed to pass legislation through the socially conservative House to help minors on the Children’s Health Insurance Program obtain contraceptive services and avoid teen pregnancy.

Howard won legislative passage of a measure to create a Sexual Assault Survivors Task Force in the governor’s office, funded with $3 million (the vote was 140–0). The task force will oversee improvements to crime labs and gather data on the investigations and prosecutions of sexual assault to make recommendations on how to best serve sexual assault survivors. In other bipartisan action, Howard worked with Republicans to improve college assistance for children who had been in state foster care programs. And along with a fellow nurse, Republican Stephanie Klick, Howard pushed legislation to improve the work lives of nurses by requiring health-care facilities to provide workplace-violence training and to establish a system for investigating and reporting incidents.

As the legislative session neared its close, Howard’s husband suffered a massive heart attack that left him in a coma. Even faced with this devastating news, Howard continued to soldier on in the House, working for her constituents and for the principles she holds dear.

Back to List ⤒

Representative Dade Phelan

R-Beaumont

Dade Phelan had some of the biggest shoes to fill this session of any lawmaker. A former aide to U.S. House majority leader Dick Armey, the Beaumont Republican had served just two terms before he was appointed to lead the House State Affairs Committee this session. State Affairs is one of the Legislature’s busiest crossroads, a frenetic workshop that handles an immense pileup of important and controversial bills. If all that weren’t enough, Phelan’s predecessor, Byron Cook, was one of the most formidable and respected lawmakers in the chamber, willing to listen carefully and take political heat to do what he thought was right.

We’re pleased to report that Phelan was equal to the task. He successfully managed one of the largest workloads this session, defanged some of the most controversial legislation, and still emerged with the reputation of being a gentleman—a rare moniker in the fight club that is the Legislature.

The thirty House committees handled on average 190 bills each. State Affairs was assigned 336 bills, the fourth most of any committee. Some of those bills were heard in marathon sessions that attracted hundreds to testify; the witness list for the 13-hour hearing on the “Save Chick-fil-A” bill was 67 pages long, and the hearing ended just before sunrise the following day—the longest of the session. But even during grueling hearings, Phelan made a point of listening respectfully, a contrast to colleagues who sometimes cut off testimony or were short with the public. When the Senate revived the Chick-fil-A bill after the House had killed it on a procedural motion, it did so at the last minute, hearing no public testimony and giving little warning.

Phelan also showed courage as committee chairman. State Affairs was tasked with hearing a raft of Senate bills to overturn local ordinances to protect workers, including paid sick leave ordinances in Austin, San Antonio, and Dallas. LGBTQ opponents of the bills feared that they would also invalidate local nondiscrimination ordinances that protect LGBTQ employees. Following an eight-hour hearing, Phelan, knowing he would draw the consternation of the Senate leadership, added language to keep the nondiscrimination clauses intact.

Phelan also passed legislation that would allow the attorney general to act against freestanding emergency rooms that charge “unconscionable” rates to patients, defined as 200 percent above what the average hospital charges. And he was the lead House author of a Harvey relief package that drew around $1.7 billion from the state’s Rainy Day Fund.

The day after the 86th Legislature left town, Phelan tweeted about his committee’s upcoming schedule during the interim: “Looking forward [to] getting back to work.” Attaboy.

Back to List ⤒

Representative Victoria Neave

D-Dallas

Victoria Neave had a rough start as a lawmaker. Elected in 2016 to represent a swing district in Dallas as a result of that year’s most expensive state house race, she came to Austin with high expectations, but topped off an adequate first session with a DWI charge, delivering to officers after she’d plowed into a tree the immortal declaration that “I love you and I will fight for you and I’m invoking my Fifth Amendment rights.” Earlier this year, Neave admitted that she has been having personal financial difficulties and owed $26,000 in back property taxes.

But Neave’s second term has been a vast improvement, and the state is better off for it, if for only one reason: Neave’s passage of the Lavinia Masters Act, which aims to close the state’s rape-kit backlog. In 1985 Masters, then thirteen, was raped in Dallas, and her rape kit sat untested for more than twenty years. When it finally was tested, a suspect was identified, but the statute of limitations had run out. In the meantime, he had assaulted more women. There are thousands of untested rape kits left in Texas, often sitting in storage because of the cost of processing.

Neave’s bill goes a long way toward solving the issue by providing money for testing, improving state crime labs, and pausing the statute of limitations until a rape kit has been tested. It passed the House 145–0 and sailed through to the governor’s office.

If that makes the bill sound like less of an accomplishment—of course it passed, you might think, who wouldn’t support it?—know that this is an issue that the Legislature hasn’t bothered to fix for many years. In 2013, after state senator Wendy Davis pushed through a requirement that the state audit the number of untested rape kits lying around, DPS reported that there were some 15,000 to 20,000, and that it might cost something like $10 million to clear them.

That’s chump change in a state that regularly spends $800 million a year on nebulous “border security” operations, but year after year, the Legislature preferred to apply band-aids rather than fix the problem. One suspects that if the gender balance in the Lege was closer to 1:1 instead of 3:1, the money would have been found in about five minutes. That not being the case, the backlog continued to accumulate.

Enter Victoria Neave. In 2017, she passed a program that allowed the public to donate to ending the backlog, which eventually raised some $560,000 by the start of this session. As a policy fix, it was far from adequate, but the shameful optics of the state crowdfunding such a basic component of its public safety responsibilities helped draw broader attention to the problem.

This year, Neave came back with a more comprehensive plan, which became House Bill 8. (The low bill number signified that it was a priority of Speaker Bonnen’s.) Neave’s success in passing HB 8 was in part because of broad bipartisan interest and the desire of Democrats to give her a suitable win to bring back to her swing district. “DWI?” joked one lobbyist. “What DWI? Well done.” But it was her focus on this issue across her two sessions that helped bring the issue to the fore and ensure its passage.

Very slowly, the Texas Legislature is looking more like the people it represents. The passage of the Lavinia Masters Act could have happened at any point in the last decade. It happened now in part because new voices like Neave’s are demanding to be heard, and that’s a great thing for the state.

Back to List ⤒

Senator Kirk Watson

D-Austin

David Whitley’s nomination to serve as Texas secretary of state should have been doomed by his own incompetence, but that’s not how things work at the National Laboratory for Bad Government. After Whitley, in his capacity as interim secretary of state, bungled an effort to root out voter fraud, falsely accusing tens of thousands of Texans of illegally voting, Democrats desperately needed to block his nomination, and deal Governor Greg Abbott a rare political blow in the process. But who, among the feckless Senate Democrats, would administer the coup de grace? Senator Kirk Watson raised his hand—and his executioner’s sword.

The beginning of the end for Whitley came in early February, when Watson, an Austin liberal with a drawl and a Baylor law degree, summoned the spirit of legendary attorney Richard “Racehorse” Haynes to witheringly cross-examine Whitley during his nomination hearing. In a methodical line of questioning that lasted more than an hour, Watson pushed Whitley to explain why he had disseminated a list of 95,000 suspect voters to local voting officials and the Texas attorney general without doing basic due diligence.

Would he consider asking the attorney general to hold off on investigating voters until the list was scrubbed of legitimate voters? Whitley offered a characteristically vague response: It was a “reasonable request,” but he just didn’t think the list-scrubbing was “appropriate.”

“If you weren’t at least attempting to create the appearance of illegal activity, then there’s no reason or explanation for immediately referring 95,000 people to the Office of the Attorney General,” Watson charged.

By the end of the hearing, Whitley’s credibility was in tatters, and the longtime trusted aide to the governor was on the path to an embarrassing political failure.

Watson’s effort to derail Whitley’s nomination is significant enough itself to get him on the best list this year. But the former Austin mayor wanted to run up the score. He was integral to killing a one percent state sales tax hike; he helped make government more transparent with a slew of public information laws; he strengthened the protections for victims of sexual abuse; and he pushed through a number of child-care initiatives that advocates had been pushing for since the George W. Bush administration. For a progressive Austin Democrat in Dan Patrick’s fiefdom, this is the kind of substantive agenda with broad appeal that can actually get accomplished.

For his part, Whitley fought for his job till the bitter end. He made his apologies, went on a “voting rights history tour” in Alabama, and promised the Democrats to consult with voting rights groups on any future lists. To everyone’s surprise, the Senate Democrats—who typically suffer from an acute case of Stockholm syndrome—held firm. Whitley had vowed to increase election integrity in Texas, and he did so, by resigning his post shortly before the end of session and going back to work for Abbott in the governor’s office. A happy ending, as far as these things go, one Watson had helped make possible.

Back to List ⤒

Representative Tom Oliverson

R-Cypress

The rising costs and staggering inefficiencies of the American health care system constitute a tax on both people’s pocketbooks and well-being. This is obvious to anyone who’s had a mind-bending, possibly bankruptcy-inducing, experience with an insurance company, hospital, or clinic. In a less dysfunctional political environment, Republicans and Democrats would be competing to see who could make this broken system cheaper and better.

But Republicans have generally been content with the perception that health care reform is an issue for Democrats. In the last decade, the GOP-controlled Texas Legislature has done little of substance other than squeezing the state’s Medicaid program. Perhaps the 86th Legislature’s biggest public health story, at least by volume of national media attention, came when Representative Jonathan Stickland (see “The Cockroach”) described vaccines as “sorcery.”

So it was a pleasant surprise to see Tom Oliverson, an anesthesiologist from Cypress and the vice chair of the House Committee on Insurance, practicing good medicine this session.

Unlike some of the House’s other physicians—Republicans John Zerwas and J. D. Sheffield, for example—Oliverson is firmly on the right wing of his party. But he happily works with people from across the ideological spectrum, including moderate Republicans and Democrats like San Antonio’s Trey Martinez Fischer. He’s often described as a polite and earnest man with a voracious appetite for learning about health care policy. The doctors trust him and so do consumer advocates, an important factor in forging consensus.

Oliverson helped pass several bills that should make the state a better place to be sick, including legislation to mandate arbitration in the case of “surprise” medical bills, a bill to force freestanding emergency rooms to clearly disclose what insurance plans they accept, and a measure to bring transparency to the opaque practices of pharmacy benefit managers, middlemen who help drive up drug costs. When Senator Kelly Hancock insisted that his version of the surprise-medical-billing ban be the one to move forward, Oliverson was instrumental in defusing the standoff.

But it was Oliverson’s drug-price-transparency plan that was the most unforeseen success. Under his bill, pharmaceutical companies that raise the price of drugs past a certain threshold will have to turn over information about the increase to state authorities, a requirement advocates hope will pressure the companies to think twice about jacking up prices in the first place. Oliverson originally set the tripwire for disclosure at a 50 percent price increase a year. Anything more strict, he believed, wouldn’t get through the House and would draw the opposition of Big Pharma, which had endorsed his proposal.

The House pleasantly surprised him, however, voting on the floor to ratchet down the rate to 10 percent—a change that Oliverson came to embrace. At that point the industry panicked and turned on him, demanding that he scrap the bill. But the lobby was too late. Oliverson held firm, and eventually the legislation passed with a 15 percent cap. Drug price shocks have taken up space in the national discourse for years, and now, thanks in part to Oliverson, Texas has one of the strongest transparency laws in the country. Who’da thunk it?

Back to List ⤒

The Worst

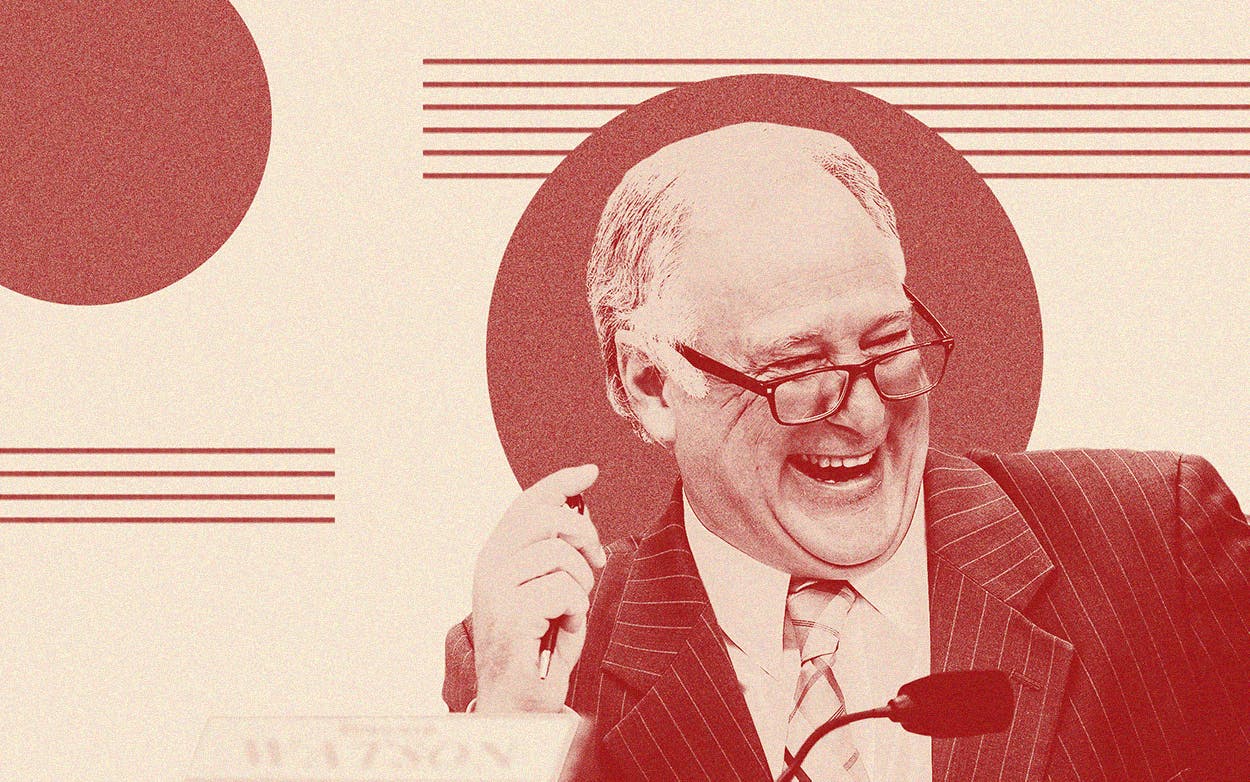

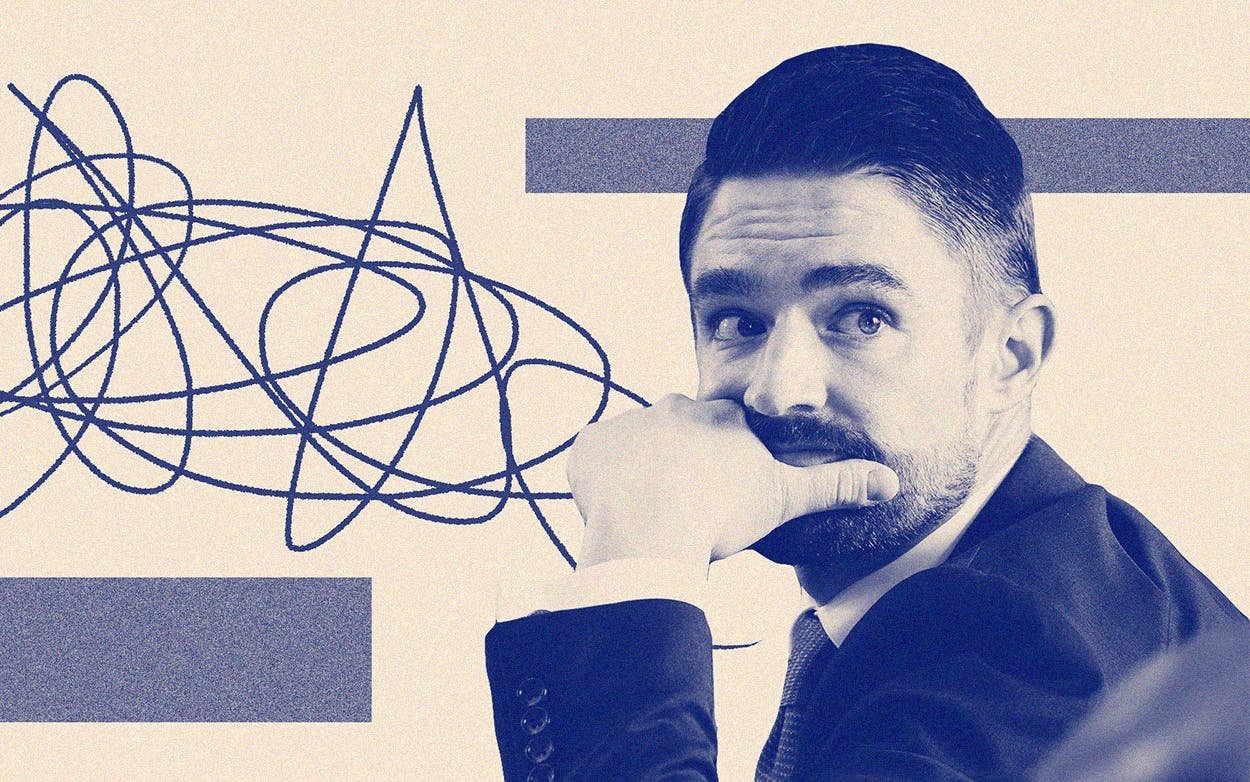

Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick

Dan Patrick’s ascension as lieutenant governor felt like the mad prophet Savonarola’s takeover of Renaissance Florence. Men of unquestioning certainty and righteousness, Patrick and Savonarola knocked over the old order—David Dewhurst and the Medicis, respectively—and promised a new era of prosperity and happiness ordered by a commitment to God’s plan. In his first inaugural address, Patrick promised his arrival marked “a new day for Texas.” Though he had no trouble driving the narrative of each subsequent session, he had a lot of trouble getting his priorities through. In 2017, he used all of his accumulated power to fight a war to regulate where school children urinated. He lost.

Perhaps the bathroom bill failure broke something in him—or maybe the tide had just crested, just as Savonarola’s movement eventually waned because “he had no means of keeping steadfast those who believed or of making the unbelievers to believe,” as Machiavelli put it. Dan Patrick’s challenge this session, with reduced Republican majorities, was to make ’em believe again. In his inaugural address in January, he declared that this legislative session would be “the greatest session ever in the history of Texas.”

But he missed the opening day of the 86th Legislature to be with President Donald Trump before the president’s primetime address on the border wall. Patrick then was AWOL on the day the Senate was initially scheduled to consider his top legislative priority—legislation to slow the upward creep of property taxes—again to be with Trump. Throughout the session Patrick seemed absent. While senators hammered out deals on property taxes, education, and the budget, Patrick made more than a dozen appearances on Fox News to discuss border security. Many wondered if he was auditioning for a cabinet job.

Instead of paying attention to legislative details, Patrick led by intimidation, generating a new level of enmity in the upper chamber. Once, Patrick’s enemies were the world at large—liberals, RINOs, and the media foremost among them. This year, his enemies were in the Senate chamber: from nearly powerless Senate Democrats to his old friend and fellow Republican Paul Bettencourt, who lead the charge against the ill-conceived idea of hiking the sales tax rate to pay for property tax relief.

But it was his fight with Senator Kel Seliger, of Amarillo, perhaps the chamber’s last mainstream Republican, that encapsulated Patrick’s session. He began by taking away Seliger’s chairmanship in retaliation for his outspoken opposition to several of Patrick’s priorities last session. When a Patrick senior advisor chided Seliger for complaining, Seliger told her to shove it, for which he was stripped of yet another chairmanship. When Seliger resisted voting for Patrick’s cap on property tax revenue, the lite guv threatened to change Senate rules to get his way, forcing a dramatic showdown on the floor that ended with Seliger calling out Patrick but nonetheless allowing the legislation to move forward.

It’s no secret that Patrick and Seliger have long disliked each other. Nor is it a secret that a primary challenger whom Seliger faced in 2018 was advised by one of Patrick’s longtime allies, Allen Blakemore.

But when the spat went public, Patrick expressed innocence. “Nobody knows what he’s angry about,” Patrick told the Dallas Morning News, adding that the night before, Patrick and other Republican senators “held hands and prayed for him.” (Seliger is Jewish.) It’s that kind of insincere high-horsing that has soured a lot of people on Patrick. On sine die, he looked less like a prophet than a flim-flam tent revival preacher—not Savonarola, but Elmer Gantry.

Back to List ⤒

Representative Tom Craddick

R-Midland

Tom Craddick may be the Legislature’s best argument for term limits. We’re not suggesting legislators be forced out of office after two or even ten terms. But after 26 terms, isn’t it time to focus on your golf swing or spend more time with the grandkids? First elected in 1968, the same year Richard Nixon was elected president, Craddick had already served in the House for two decades when the chamber’s youngest current member, James Talarico of Williamson County, was born. When Craddick’s authoritarian reign as speaker came to an end in 2009 amid a revolt of the members, some thought his political career would finally wind down. That was ten years ago.

But it’s not Craddick’s longevity that’s ultimately the problem. It’s that experience hasn’t brought wisdom. This session, the 75-year-old West Texas oilman was back in touch with his dark side—the one that made his speakership such a travesty.

In a series of extraordinary moves, Craddick killed a carefully crafted piece of eminent domain reform that sought to balance landowners’ rights with the needs of pipeline operators. In a very un-West Texas-like fashion, he did it in an underhanded manner and then apparently lied about the series of events that led to the bill’s demise.

The legislation was months in the making and involved negotiation among the agricultural industry, oil and gas interests, and regular citizens concerned about the proliferation of new pipelines slated for rural areas. Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick hosted talks late in the session to develop something that could pass the oil-drenched Legislature. The result was a compromise that the parties at the table declared fair. But when the gift-wrapped package arrived at the House from the Senate, Craddick began his plotting.

Traditionally such legislation would go to the House sponsor of a bill, in this case Representative DeWayne Burns, R-Cleburne, who had been involved in the issue since the get-go. But Craddick used his authority as a committee chairman to hijack the bill—an extremely rare move—and then gut it, telling his hometown newspaper that it tilted too far in favor of landowners. In another unusual tactic, the House then tried to undo the damage Craddick had done by voting to instruct the House conferees to resurrect the compromise language in conference committee with the Senate. Once again, Craddick found a way to play spoiler. When the five House negotiators were announced, boos erupted in the chamber—Craddick was the chairman of the conference committee, and Burns hadn’t even made the list.

In conference committee, all five Senate members agreed to restore the compromise bill, but Senator Lois Kolkhorst, who carried the bill in the Senate, couldn’t get Craddick to sign on.

The next day, Craddick’s office issued a press release declaring the bill dead. “The Senate failed to respond to our last eminent domain bill,” Craddick said in the statement. “Senator Kolkhorst [sic] office made no effort to meet with me since the bill left the House.” Several people close to the negotiations said the statement was simply a lie. One lawmaker had even snapped a photo of Kolkhorst meeting with Craddick to discuss the issue.

Not only had Craddick sabotaged eveyone’s hard work, he’d shamelessly tried to shift the blame. His shenanigans were compounded by the fact that he had violated Ronald Reagan’s Eleventh Commandment that Republicans should not speak ill of other Republicans. Perhaps snuffing out this bill is Craddick’s last favor to himself and his pals at the Midland Petroleum Club. But we doubt it; the smart money is he’ll be back in 2021, ready to serve his 27th term.

Back to List ⤒

Senator Bryan Hughes

R-Mineola

Bryan Hughes may be one of the nicest lawmakers in the Senate chambers. He’s an aw-shucks country lawyer with a firm handshake and twinkling green eyes. Unflappable and well-prepared, Hughes is a conservative workhorse—the third-most-prolific author of legislation in the Senate this session.

So why is he on our Worst list this year? Because the 49-year-old Mineola native used his talents and passions to kick down, particularly at poor folks, people of color, and the LGBTQ community. In relitigating the culture wars and, at times, quite literally, bringing his colleagues to tears, Hughes seemed intent on poisoning what many were hoping would be strictly a “kumbaya” session focused on solving policy puzzles like school finance. There was something ludicrous and sad about watching Hughes spend so much energy trying to “save Chick-fil-A”—as if the gay-unfriendly chicken chain was in danger of going under because the San Antonio City Council decided to ban it from the San Antonio airport.

To LGBTQ folks, the “Save Chick-fil-A” legislation was less about religious liberty than a thinly veiled attempt to resurrect the hateful optics of last session’s bathroom bill. At least two members of the LGBTQ caucus cautioned tearfully not to sanction bigotry in the name of religious liberty. If there were ever anything of substance in the bill, by the time the thing had slimed its way through the process, it had become largely symbolic—a totem of the smiling, feigned ignorance that Hughes’s colleagues are well familiar with.

One senator noted that Hughes has a tendency to answer his colleagues’ questions about the effects of his controversial bills by prefacing his responses with the lawyerly disclaimer, “It’s my understanding. . .” Wouldn’t his “Save Chick-fil-A” bill undo local nondiscrimination ordinances, as many legal experts contended? Not in Hughes’s understanding. Wouldn’t the legislation empower business owners to discriminate by protecting them against “adverse actions” based on their “sincerely held religious beliefs,” as the plain text of the bill suggested? Not in Hughes’s understanding. Once the bill was watered down, wasn’t it just restating basic First Amendment protections? Not in Hughes’s understanding. All session long, Hughes hid behind his “understanding”—seemingly incapable of understanding the harm his proposals could do.

While he was trying to convince his colleagues that his legislation wasn’t a license to discriminate, he was simultaneously pushing a proposal to prohibit social media companies like Facebook and Twitter from moderating users and their posts on the theory that conservatives are treated unfairly on such platforms. “They shouldn’t be able to discriminate based on content,” Hughes declared. Add irony to the list of things the senator doesn’t understand.

Back to List ⤒

Representative Poncho Nevárez

D-Eagle Pass

Poncho Nevárez is a package deal. His motto might as well be: If you can’t handle me at my worst, you don’t deserve me at my best. The same qualities that can make him fun to watch when he’s on your team make him unbearable when he’s not, and most people in the House have experienced both. He’s hotheaded, assertive, mischievous, and prone to brawling, perhaps the preeminent posturer of the lower chamber. But the Lege saw a lot more of Nevárez’s demons this session than his better angels, whom he might have left in Eagle Pass. The man sorely needed less testosterone and more humility.

Criminal justice reform advocates had high hopes for Nevárez’s Homeland Security and Public Safety Committee this session, but by the end, some of them were privately yearning for his predecessor Phil King, who never saw a police power he didn’t like but nonetheless had a reputation as a straight shooter. In hearings Nevárez’s cranky side often came out to play, and in private even his allies couldn’t know for sure if he was telling the truth when he said he didn’t have the votes to move bills.

Nevárez often gave the impression he believed the Legislature was divided into two factions: pro-Poncho and anti-Poncho. Weeks after his committee passed a measure that would let citizens carry loaded handguns without permits for a week after a declared natural disaster—a bill that sets up the exciting prospect of pistol-packing anti-looter patrols after the next hurricane—a gun control mom tweeted a mild criticism of the bill that tagged Nevárez. He responded: “Ma’am, it is apparent that I’m only as good to you as my last favor,” sounding a bit like a mob boss. “I’ll keep that in mind. God bless you.”

Nevárez’s penchant for sleight of hand sometimes produced good results, like when he helped neuter a cockamamie bill to fund border-wall construction by helping to convince its author to turn it into a general infrastructure bank for border counties. But more often, he just made a mess. In one confusing exchange, he helped kill a bill limiting arrests for fine-only offenses by charging that a specific provision of the bill would lead to racial profiling. It quickly emerged that Nevárez had previously proposed the same provision for the same bill. He then claimed that the amendment had been filed by someone in his office without him ever reading it.

But the finale of the Poncho Nevárez Show made the rest of his routine look like side acts. In a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it maneuver during the last week of session, he tacked a curious eleventh-hour amendment onto an uncontroversial bill that strengthened protections for domestic violence victims. Nevárez tried to gloss over the substance of the thing by calling it “some economic competitive incentives,” before quickly moving passage.

Whole fortunes have been made and lost in moments like that, when lawmakers pretend to be doing nothing interesting, and closer scrutiny bore that out here. Nevárez had used his own bill to try to turn a favor for politically influential company that operates a radioactive waste dump in West Texas—a dump that’s not even in his district. The “incentives” turned out to be a postponement of new fees, worth about $4 million to the company. The bill’s author, Senator Lois Kolkhorst, told the media she had been blindsided by Nevárez’s amendment, but accepted it in order to keep the bill alive. Not that it mattered—the governor vetoed it, calling out Nevárez for his shamelessness. Nevárez, true to form, suggested it was Abbott who didn’t care enough about domestic violence.

Back to List ⤒

Senator Angela Paxton

R-McKinney

Conflict of interest isn’t so much a problem to be avoided in the Texas Legislature as it is something to get away with and profit from. But even within the dubious traditions of the institution, Angela Paxton stands out for sheer audaciousness, particularly as a first-term senator.

Paxton is a Christian academy math teacher and conservative activist who earned minor fame for a song she wrote and performed in homage to her husband, a little ditty that includes the lyric: “I’m a pistol-packin’ mama / and my husband sues Obama.” That husband is Texas attorney general Ken Paxton, the state’s law-averse lawman, who has been under indictment on a state securities fraud charge stemming from his private law practice and who, when in the Legislature, had conflict-of-interest problems following him around like Pig-Pen’s dust cloud.

Her husband’s track record notwithstanding, after her election win last year, it seemed like Angela Paxton was going to be one more Christian conservative with a tea party bent serving in a chamber controlled by like-minded lawmakers. And as a freshman, she generally got good marks for working closely with veteran senators as she sought to understand the arcane rules of the chamber.

But then she shocked the conscience of the Senate—no easy thing to do—by filing legislation relating to “the creation of a regulatory sandbox program administered by the attorney general for certain financial products and services.” Benign as that may sound, it would have given her husband the power to rewrite the very set of financial security regulations that he is accused of violating. Though the law wouldn’t have been retroactive, it could have given him another plank in his legal defense. In a more enlightened lawmaking body, Paxton might have been expected to abstain from any matter pertaining to her husband’s workplace. Instead, she acted with all the subtlety and grace of a Sicilian crime family.

When called out for her deeds, Paxton did her best pearl-clutching act, claiming that the bill had “literally nothing to do” with her husband’s criminal charges. The whole thing was a reminder why there are laws against nepotism. While senators ultimately forgave her for the legislation—particularly since it died a much-deserved death in committee—they were amused that the legislation aimed at helping her husband only drew attention to his ongoing legal woes.

The good news for Angela and Ken Paxton is they don’t face voters again until 2022. The bad news for Texas is that this pistol-packin’ mama and her husband don’t face voters again until 2022.

Back to List ⤒

Representative Jeff Leach

R-Plano

Jeff Leach is a man of convictions and righteous indignation—until he’s not. Since his election to the House in 2012, Leach has been one of its most conservative members. Leach routinely opposed Joe Straus as speaker. In 2017, he was a founding member of the House Freedom Caucus—a kind of far-right frat house where nuance and compassion go to die. Later that year, Leach was a leader of the so-called Mother’s Day Massacre, killing more than a hundred bills in a fit of pique over conservative legislation not getting aired in the House. Generically good-looking in a “megachurch youth minister” sort of way, Leach was the genial poster child for the evangelical tea party, bomb-thrower wing of the GOP.

Then the 2018 elections happened. A little-known Democrat nearly defeated Leach, and suddenly he found a new religion: cozying up to power. Leach resigned from the Freedom Caucus and endorsed Republican Dennis Bonnen for speaker. This newfound obsequiousness earned Leach the chairmanship of the powerful House Committee on Judiciary and Civil Jurisprudence. So, what did the outsider turned insider do with his newfound influence?

Leach received high marks in some quarters for pushing a judicial pay raise unlinked from legislative pensions. And in one moving instance, his wife, Becky, brought tears to Leach’s eyes when she testified in front of his committee about the sexual abuse she suffered as a teenager.

Behind the scenes, many legislators and lobbyists find Leach to be a rather unhappy warrior, a man caught between his high-minded principles and his new influence.

In his committee, Leach tried to play both sides on abortion. Just two years ago, Leach was the coauthor of an Alabama-worthy anti-abortion bill that would’ve made it possible to impose the death penalty for women who have abortions and the doctors who perform them. It was so extreme that the Republican chairman refused to even give the bill a hearing. In early April, Moderate Jeff declared that he wouldn’t let a near-identical piece of legislation out of his committee, dubbing it a “bad bill.” Yet he held a hearing on it for the next week anyway. In doing so, Leach unleashed a torturous, and ultimately pointless, six-hour bloodletting that upset and frustrated almost everyone.

During the hearing, a young legislative intern from NARAL Pro-Choice Texas testified, and Leach chose to badger her about the group’s Twitter feed. He continued his attack even after she made clear she had nothing to do with the Twitter account. She addressed him as “Representative Leach”; he snapped back, “Chairman Leach.”

The hearings disturbed people who supported abortion rights, but also gave false hope to supporters of the legislation that their testimony might change Leach’s mind. The ugliness of the matter was underscored when some supporters of the bill threatened Leach, prompting increased security for his protection.

Meanwhile, Leach won House approval of his own “born alive” bill, creating a third-degree felony punishable by up to ten years in prison for any doctor who would fail to provide “appropriate medical treatment” for a baby born alive after a failed abortion. Given that there have been no recorded live births after an abortion in Texas, this seemed more like a cynical ploy to appease anti-abortion activists while stigmatizing women.

We would never hold a politician to a standard that precludes a change of heart. But to whipsaw around for power and to pander to voters is the worst kind of political gamesmanship. Jeff Leach was in it for himself in 2019, and that made him one of the Worst.

Back to List ⤒

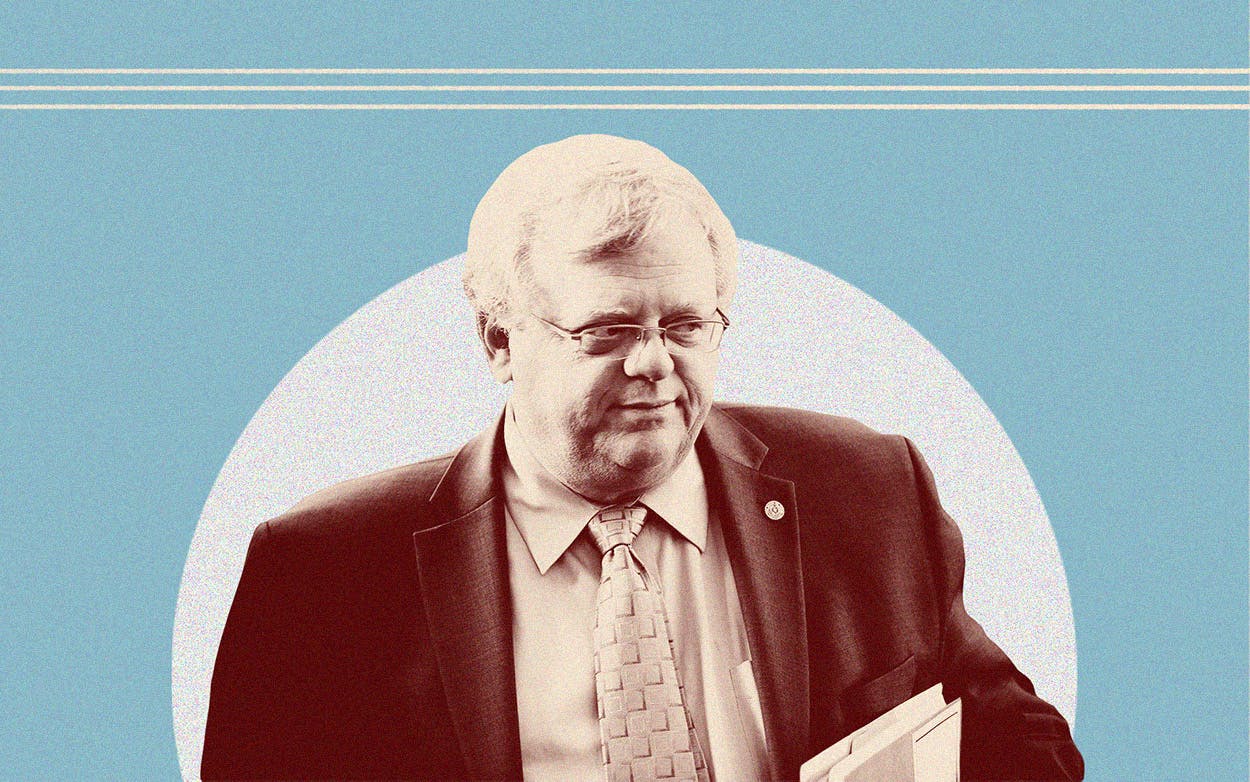

Senator John Whitmire

D-Houston

John Whitmire is a titan of the Legislature. He was elected to the Texas House in 1972, serving there until his election to the Senate in 1982. He is as much a part of the Capitol as the bronze hinges on the building’s doors. The only Democrat allowed to retain his committee chairmanship after Dan Patrick came to power as lieutenant governor, Whitmire leads the Senate Committee on Criminal Justice. In the aughts, he worked with Governor Rick Perry and others to reduce the state’s prison population.

But that was last decade. This session, Whitmire’s committee was where reforms went to die. On many pressing issues, from reducing the criminal penalty for marijuana possession to police accountability measures, he was either very slow to hear legislation or never got around to giving bills an airing. He’d freeze action on Senate bills until the House passed their versions, or he’d lock up bills in his committee if Patrick said he wouldn’t let them pass the Senate.

This do-little strategy may well have been politically astute. It left the tiring burden of negotiating, and taking heat from special interests, to the lower chamber, and it saved him the trouble of handling tricky proposals that someone else was going to kill. But good lawmakers don’t take the path of least resistance—they try their best to overcome obstacles. That’s what the dean—as Whitmire is known—used to do. All session, the question lingered: What, exactly, is Whitmire willing to fight for these days?

A bill reducing criminal penalties for pot possession that landed in his committee in February never even got a hearing. When the lower chamber passed a watered-down bill by a surprisingly strong margin at the end of April, and Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick vowed to kill it, Whitmire responded that he would try his best to get the bill to the Senate floor. But it was too late—he had squandered his chance to build pressure behind the issue. Whitmire well knows that it can take several sessions, maybe even a career, to advance major legislation. You can win the long game by losing a little less each time. But you still have to try. Whitmire doesn’t seem to have much “try” left.

In his committee’s last meeting this session, Whitmire and Senator Borris Miles patted each other on the back over their gutting of a House bill that would have put a system in place to determine whether death-penalty-eligible defendants are intellectually disabled. Once upon a time, the Texas Legislature would never have dreamed of touching such a thing, but the House had sent the bill over to the Senate on a resounding 102-to-37 vote. Through Whitmire’s intervention, it transformed from, as one advocate put it, “a bill to a piece of paper with words on it”— a measure that simply restated the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling that mentally disabled persons should not be executed.

Elsa Alcala, a top Republican judge turned criminal justice reformer, was furious. “It’s meaningless; it’s worthless; it’s not worth the paper it’s written on,” she said, after demanding to testify. Whitmire chided her as if he were speaking to a small child: “You’re sitting here being halfway rude to the people that ultimately will help you fix the problem,” he said. “You don’t have a monopoly on caring.”

Neither does Whitmire. At other points in the session, he employed tough-on-crime talk that seemed to come from a bygone era. In a hearing on juvenile-justice issues, he proposed moving the entire remaining population of the state’s juvenile lockups to a recently shuttered adult prison, calling the youth a “very tough population” in an extended monologue that caught observers by surprise. He also engaged in an out-of-left field crusade against the state’s practice of reading the last remarks of executed persons to the media.

Whitmire has done many good things in his 46-year stint at the Capitol. But at this point, his main evidence of success is the size of his campaign checking account, which hit $2.5 million in 2005, $5 million in 2011, and $8.5 million during the last election cycle. It sits there, growing and growing, warding off primary challengers, as his influence—and his willingness to fight—shrinks and shrinks.

Back to List ⤒

Senator Brandon Creighton

R-Conroe

When Senator Brandon Creighton laid out his bill to create major hurdles for state and local governments that want to remove monuments, he tried to focus the debate on such controversies as the Ten Commandments monument on the Capitol grounds and the Alamo Cenotaph. It was as if Creighton thought everyone would forget about the real issue—communities removing Confederate monuments from the public square—if he were obtuse enough. He didn’t fool anyone, least of all the Senate’s black and Hispanic lawmakers, one of whom called the bill “disgraceful.”

Creighton tried to prettify his thinly disguised Lost Cause cause with a just-so story about a heroic ancestor. “My four-times great-grandfather was part of Terry’s Texas Rangers,” Creighton said. “He served to keep Texas safe and protected.” He told the Senate that he fondly remembers this ancestor every time he sees the monument to Terry’s Texas Rangers on the Capitol grounds. “I’m reminded of that family history in law enforcement and the sacrifice he made for the state of Texas.”

With his own words, Creighton proved that monuments do not necessarily teach history.

The Capitol monument of a man on horseback with a rifle in hand has nothing to do with law enforcement. Contrary to a common opinion, Terry’s Texas Rangers was not a branch of the Texas Rangers. It was the nickname for the 8th Texas Cavalry, a Confederate regiment that fought under Nathan Bedford Forrest, who would later go on to serve as the KKK’s first Grand Wizard. In fact, many of these “Rangers” kept slaves as manservants. In 1863, one of the Rangers wrote home that the Texans would take no prisoners if they ever encountered black troops, A year later, the regiment was present at the Battle of Fort Pillow, where almost two hundred black federal troops were massacred as they attempted to surrender. Fort Pillow was one of the worst atrocities of the Civil War.

Creighton’s ignorance of his family history—whether willful or merely misguided—shows how little even some defenders of Confederate monuments know about them. But for Creighton to make the worst list, it took more than a single racially inflammatory bill. Just as bad was his hypocrisy; by trying to preempt a local government’s decisions, he violated his own supposed principles.

In 2015, Creighton won Senate approval of a resolution reaffirming Tenth Amendment “state sovereignty” from federal government dictates, part of a longstanding conservative attempt to devolve power to the states. Yet this year, he had no problem trying to serve as the majordomo for the cities and counties of Texas, blithely running roughshod over the Texas tradition of “local control.” More than 350 cities in Texas are home-rule municipalities, with extensive powers of self-governance granted by the state. This session, Creighton tried (unsuccessfully) to ban cities and counties from hiring paid lobbyists and pushed legislation to overturn local ordinances requiring paid sick leave for workers.

Hypocrisy comes cheap at the Legislature, but rarely does a politician waste it on such monumentally small causes.

Back to List ⤒

Special Awards

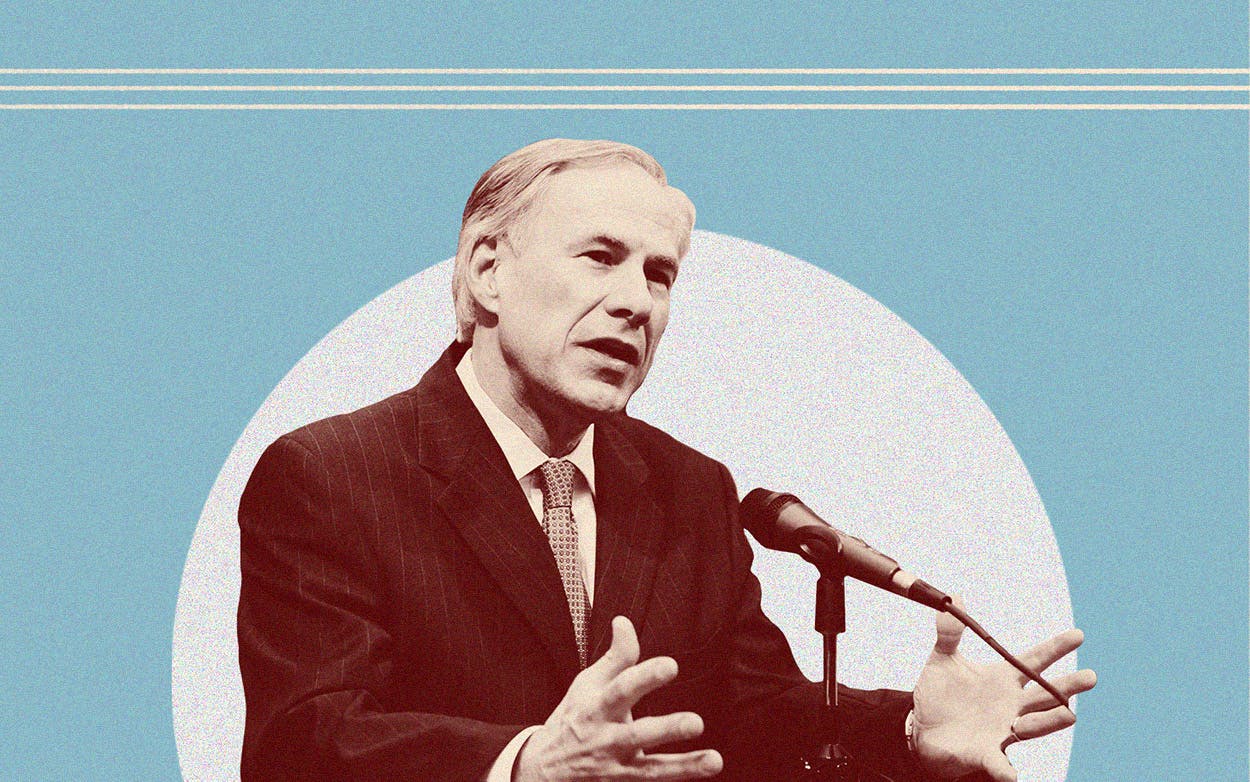

Most Improved

Governor Greg Abbott

In his first two legislative sessions as governor, Greg Abbott developed a reputation as an untrustworthy bully, an unreliable negotiator who surprised everyone with eleventh-hour demands after compromises had already been reached.

In 2015, he promised Republican lawmakers that if they would buck the tea party activists by funding partial-day pre-kindergarten, he would support them in their 2016 reelection bids. Then he didn’t lift a finger. In 2017, the governor was so AWOL from the Capitol that the Legislature stumbled into a special session. (On the other hand, Abbott’s laundry list of priorities did pass during that overtime round of lawmaking.) Next, miffed at Republicans who had criticized him, Abbott poured millions of dollars of his campaign fund into efforts to defeat three House incumbents in the 2018 Republican primary. Two won reelection anyway, and the third probably would have lost even without Abbott’s intervention. So much winning!

Meet the new Greg Abbott. Maybe his thirteen-point reelection victory in 2018 gave him greater confidence in dealing with Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick (who retained his office by less than five percentage points). Maybe it was having a new staff more attuned to the Legislature. Or maybe he finally realized that a governor is supposed to . . . govern. Whatever it was, Abbott was a different man this session. He was involved and confident in what he wanted. From the beginning, he was at the table for negotiations over the public school finance overhaul and property tax cuts. The governor also made frequent visits to the House floor to sell his program—and himself—to legislators. In what was described as a “bury the hatchet” moment, Abbott was photographed shaking hands with one of the Republicans he tried to defeat. Gone were the whispers of back-room temper tantrums.

The result? For the first time in more than thirty years, the Legislature passed a school finance overhaul during regular session without a court forcing them to do so. Lawmakers gave Abbott a few other big policy wins, including limits on how much cities and counties can increase property tax rates. And at his urging, they created a consortium of universities to provide mental health services to schools in hopes of preventing another mass shooting like the one at Santa Fe High School in 2018.

At least when it comes to his legislative program, Abbott has moved from being a C governor to a B+ this session, but he’s being graded on a curve against himself. Compared to many governors who’ve come before him, Abbott is still a cipher, his legacy unknown.

Mark White and George W. Bush were education governors. Ann Richards was the breaker of barriers for women and minorities. Rick Perry was the governor of economic growth. This session, Abbott can finally take credit for some potentially transformative reforms to school finance and property taxes. But the key word is “potentially.” He and other lawmakers failed to come up with a permanent way to pay for the $11.5 billion package, and the property-tax cap may make it difficult for fast-growth communities to keep up with their burgeoning populations. If Abbott can find a lasting financial solution to this dilemma in 2021, he can prove he has a legacy and is more than just passing through the Governor’s Mansion.

Cockroach

Representative Jonathan Stickland, R-Bedford

Nobody likes a cockroach. They’re nasty and always seem to be lurking where you least want them. You can fight cockroaches, but you can’t get rid of them. They’re one of nature’s hardiest and most persistent creatures, and if nothing else, you have to admire ’em for their cussed persistence. This year, we’re giving Jonathan Stickland our first-ever Cockroach Award and enshrining the term for a lawmaker who accomplishes nothing but always manages to show up in the worst possible way.

For the last two sessions, Sticky—as both his enemies and his friends (he has a few!) call him—has made the Worst list, and he was a strong contender again this year. But since Stickland would doubtless have seen that as an achievement to boast about, we had to come up with something else.

The problem with Stickland isn’t his hyper-libertarian philosophy that the government that governs least governs best. (Though, come on, the guy once wanted to defund a community swimming pool in his hometown.) Nor is it his tea party posturing. It’s that Stickland is a completely ineffective messenger for even his own causes. He hogs the House microphone with his ravings so often that other legislators have quit listening to him.

Legislators who find themselves on the losing side of an issue often use the back mic to change votes through their eloquence and persuasion, or, failing that, to act as the conscience of the House. But Stickland goes there to get shouted down. He has the unusual power of being able to attract people to causes he opposes and repel people from causes he supports. He thinks he’s Septa Unella on Game of Thrones ringing a bell and crying, “Shame! Shame! Shame”—but in reality, he is sound and fury, signifying nothing.

We like to imagine that we are the protagonists in our own TV shows, and Stickland is no different. But part of life is knowing when you’re causing other people to turn the channel. His back-mic orations are most often reductio ad absurdum arguments against mainstream bills even when Stickland knows he won’t get enough votes to make the slightest dent in stopping legislation he opposes. For example, he was the only member of the House to vote against an overhaul of public school finance. “I feel like my district was getting the shaft,” Stickland told the Dallas Morning News. Dude, maybe that’s your fault?

At one point, he challenged state representative Sarah Davis, a Houston Republican, on an amendment she offered to a bill. “You’re not going to vote for it anyway, so if you could just”—she paused and made a down-boy motion with her hand—“uh, be quiet.”

Now, Stickland will be the first to tell you that he’s matured. Funny how a close election will make you put on your big-boy pants. He ceased ambushing his fellow legislators’ bills without warning and became more cooperative. He signed onto a bipartisan bill to create a statewide database of DNA from sex offenders. And he passed his first bill in seven years: legislation to ban red-light cameras.

But don’t kid yourself: a cockroach can’t transform itself into a butterfly. On the same day Stickland passed his first bill, he picked a needless Twitter fight with a nationally known vaccine researcher, referring to vaccinations as “sorcery.” Later, he absurdly explained that the ancient Greek word for sorcery is pharmakeia and that he is only against government-mandated vaccines. Stickland’s shtick is all Greek to us.

In one of his final acts, as the Legislature entered its home stretch, Stickland used a parliamentary rule to kill one of Governor Greg Abbott’s centerpiece proposals—a $100 million proposal to provide mental health services to the state’s high schools, an initiative inspired by the Santa Fe High School shooting. When Speaker Bonnen and other House leaders used their own legislative adroitness to resurrect the program, Stickland tried to object. Reporters in the press box near the dais heard Bonnen tell Stickland, “You’re wasting time.” Stickland blurted out, “I’m sick of this shit.”

So are we, Mr. Stickland.

Freshman of the Year

Representative Julie Johnson, D-Dallas

In 2017, the LGBTQ community defeated the so-called bathroom bill, which attacked transgender Texans on the flimsy pretext of keeping men out of the women’s restroom. But it was a joyless victory. The fight was long, ugly, and it ended in an anticlimactic way, with the bathroom bill fading away in committee when a special legislative session came to an ignominious close. Opponents, including the two LGBTQ members of the Legislature, never got the satisfaction of a knockout punch.

In 2019, things were different, thanks in part to the election of three more LGBTQ lawmakers to the House, most notably Julie Johnson, who cofounded the Lege’s first LGBTQ caucus. Johnson is a big trade up from her predecessor, Republican Matt Rinaldi, who made our 2017 list of Worst legislators for threatening to shoot one of his colleagues. Johnson, by contrast, is a paragon of collegiality. She coauthored some bills with Republicans and tried to build bipartisan goodwill by hosting a whiskey-tasting party in her office. Her wife, Dr. Susan Moster, became a member of the Legislative Ladies Club, a social group made up of the spouses of Texas House members, Democrat and Republican.

During her first session, Johnson carried a variety of nuts-and-bolts legislation, including limits on predatory practices by insurance companies as well as bills to legalize medical marijuana as a treatment for PTSD. But it was her success in defeating one of the most partisan bills of the session that put her name in lights. House Bill 3172 was crafted to prevent a government body from taking an “adverse action” against a person or contractor based on religious beliefs, and it gave the attorney general the power to sue the government on the individual’s behalf. LGBTQ activists saw it as a license to discriminate. When the San Antonio City Council voted to ban Chick-fil-A from the airport in part because of the company’s anti-gay activism, social conservatives rebranded the legislation as the “Save Chick-fil-A” bill, and it became a cause célèbre on the religious right. Each time debate on the bill came up in the House, a prominent anti-gay crusader whose wife left him for another woman in 2011 lingered in the lobby with bags of Chick-fil-A sandwiches.

Some veteran LGBTQ legislators merely wanted to go through the motions of opposing the bill. But Johnson wasn’t satisfied with half measures. She used her skills as a lawyer to convince Speaker Dennis Bonnen that the bill had violated House rules.

Ultimately, conservatives resurrected the issue with a Senate bill, but by the time it reached the House floor again, it had been watered down to the point that it was little more than an affirmation of current law. Johnson’s point of order effectively defanged it.

Choosing a Freshman of the Year was a tough decision because the Democratic class elected last year, especially the women, proved themselves to be the most dynamic freshman cohort since tea party Republicans swept into office in 2011. Ana-Maria Ramos, of Richardson, and Gina Calanni, of Katy, gave personal testimonials in opposition to a bill meant to defund Planned Parenthood, and in the process they helped scuttle two other pieces of controversial legislation. Driftwood lawmaker Erin Zwiener was described by many as the most savvy freshman and potential future leader of the House Democrats.

However, in the end, the assassination of HB 3172 could not be ignored. The LGBTQ Caucus named Julie Johnson as its Freshman of the Year. So do we.

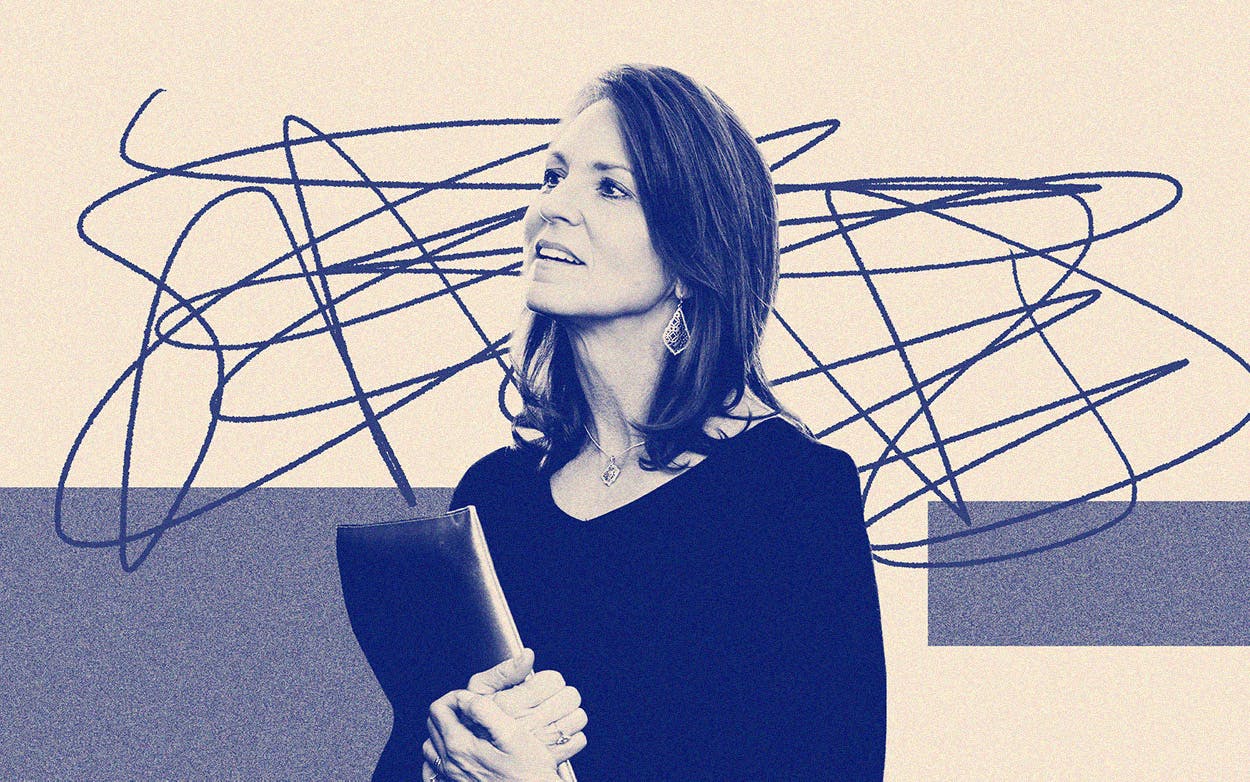

Bull of the Brazos

Senator Paul Bettencourt, R-Houston

Shaped like a bowling ball on legs, Senator Paul Bettencourt often plays the part—crashing into things and making a lot of noise. He is one of the smartest politicians in the Capitol, spewing data points, trend lines, revenue projections, and quintiles of personal income fast enough to dazzle even the well-informed listener. The problem is, the statistics are often finessed—that’s the polite word—to support his inflexible cut-taxes-at-any-cost ideology.

Affable and quick-witted, Bettencourt is difficult to dislike, unless you are a local government official who’s doing your best to provide services to your citizens. After entering the Senate in 2014 as a political soulmate of Dan Patrick, Bettencourt began a monomaniacal campaign to cap city and county property tax revenue growth. The man hates taxes so much that he has branded himself “The Taxman” and in 2008 he started a company to help businesses and individuals protest their property tax appraisals. In 2017, Bettencourt went on a PowerPoint roadshow across Texas, ginning up citizen anger over property taxes with a set of scary-looking charts that economists said made as much mathematical sense as 2+2=5. But no matter. This year, the Big Three—Patrick, Governor Greg Abbott, and Speaker Dennis Bonnen—put their organized support behind Bettencourt’s Senate Bill 2, which capped property tax growth at 3.5 percent a year before requiring voter approval.

Bettencourt’s tax-slaying dream was at hand. But then he turned on his allies.

The Big Three wanted to offer voters a proposed constitutional amendment to hike the sales tax by 1 percent in order to indefinitely pay for property tax cuts. Bettencourt immediately started working against the plan, arguing that the state should cut property taxes without raising other taxes. He went on conservative radio to make the case. He met privately with House Republicans. On the morning the House was supposed to vote on the plan, Bettencourt released a Facebook video slagging it. The tax swap was dead.

Republican House education and tax policy leaders denounced Bettencourt by name on the House floor, a rare violation of decorum. Patrick slapped Bettencourt down on Twitter and took the leadership of SB 2 away from him. Was he the goat for embarrassing the Big Three leadership and blocking a method to permanently finance property tax relief? Or was he a hero for saving Texans from a sales tax increase? In the end, the leadership did exactly what Bettencourt wanted in the first place: they used current revenue to pay for about $5 billion in property tax relief. But the plan isn’t funded past 2021. A down economy or a drop in oil severance taxes could cause this “transformational” deal to collapse. It’s possible that The Taxman has created a scenario in which a future legislature will have no choice but to raise taxes.

The duality of Paul Bettencourt is the very reason we are naming him this year’s Bull of the Brazos, a designation that goes to a legislator who is neither good nor bad but is an outsized presence in the life of the Legislature. As we wrote in 1973, when Texas Monthly first created the special award for the larger-than-life Bryan lawmaker Bill “Bull of the Brazos” Moore, “Sometimes the line between a scoundrel and a statesman can be hammered too thin to recognize.”

Furniture

The term “furniture” became a legislative term that described members who, by virtue of their indifference or ineffectiveness, were indistinguishable from their desks, chairs, and spittoons. It is now used casually and more generally to identify the most inconsequential members.

- Senator Bob Hall, R-Rockwall

- Senator Kel Seliger, R-Amarillo

- Senator Robert Nichols, R-Jacksonville

- Representative Jessica Farrar, D-Houston

Back to List ⤒

This post was updated to reflect a correction. Initially we misidentified the title of an aide to Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick. The aide is a senior advisor, not chief of staff.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Greg Abbott

- Dennis Bonnen

- Dan Patrick