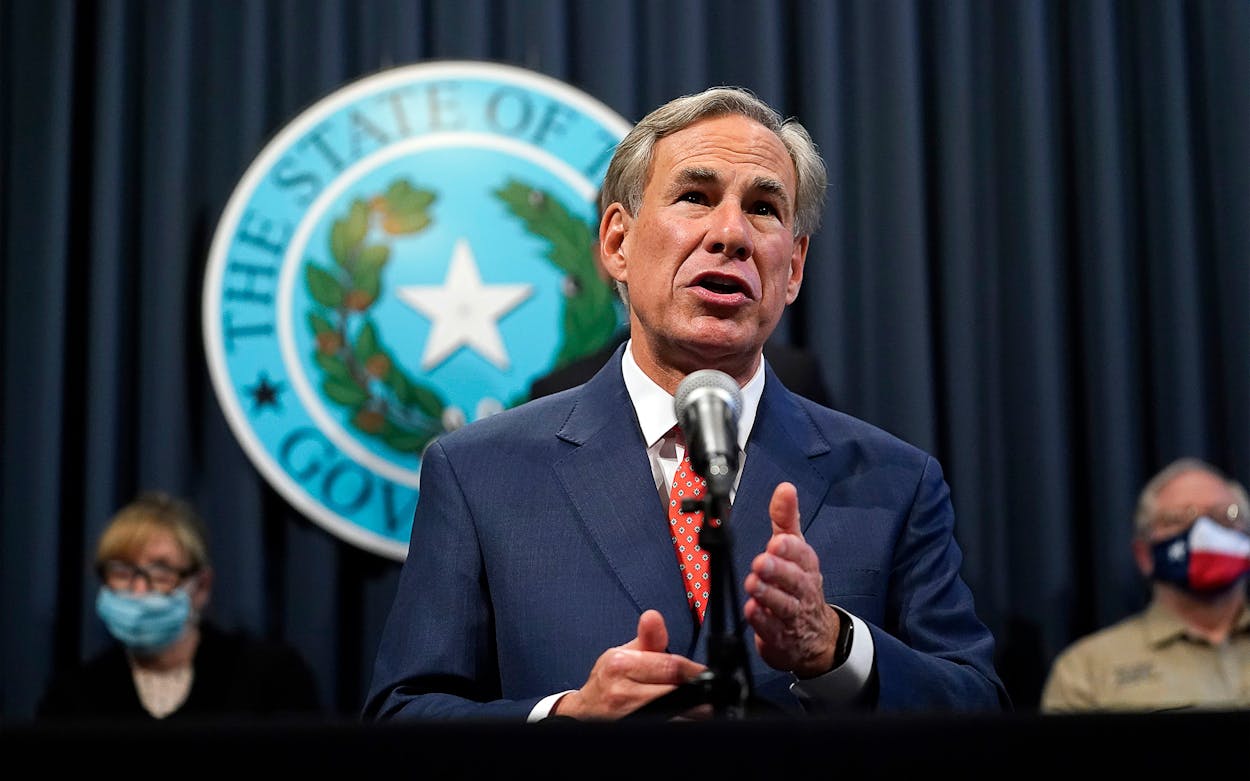

As lawsuits by Democrats proceed against Governor Greg Abbott’s order limiting Texas counties to one mail-in ballot collection location, the state’s lawyers will rely on a plausible-sounding justification for the action: to improve the “security” of the mail-in ballot process. The state will also surely argue that the order is limited in scope. Most of Texas’s 254 counties already had only one drop-off location. The rule affects mainly a few populous counties, including Harris, home of Houston, which had set up twelve collection spots for its 2.4 million registered voters. The order doesn’t technically keep anyone from voting—voters are, of course, still ostensibly able to mail in their ballots.

But put Abbott’s order in the proper context—a high-stakes battle for control of the Texas House that might be decided by razor-thin margins in races in large counties such as Harris and Bexar and Dallas, along with other contested races for the U.S. House—and it becomes transparent. Abbott’s long history of imaginative acts of voter suppression means he doesn’t deserve the benefit of the doubt. And the governor’s order raises the question of what else he might do to limit the vote by the time in-person early voting is scheduled to start on October 13.

Voter suppression comes in many flavors but varies in heavy-handedness. On one side of the spectrum, you have the government using the threat of force or punishment to bar individuals from exercising their rights. Many Americans can identify this kind of behavior as wrong. Call that the “steel-toe boot” school of voter suppression.

Texas still sees plenty of the boot. One of its most vigorous practitioners over the past two decades was Attorney General Greg Abbott, before he became governor, who was happy to give a firm kick in the kidneys to a wide range of folks who set about registering new voters and helping them cast ballots. In 2004, Gloria Meeks, a 69-year-old Black woman from Fort Worth, helped a housebound 79-year-old neighbor fill out a mail-in ballot. Because Meeks didn’t sign the envelope properly, her home was staked out in 2006 by Abbott’s investigators, whom she repeatedly saw peeping through her window at bath time. During the course of Abbott’s investigation, she had a stroke, which her friends blamed partly on the stress. She was never convicted of anything.

Around the time of the Meeks investigation, a PowerPoint presentation Abbott’s office used to brief officeholders on “electoral fraud” included a picture of Black voters in line under the heading “Poll Place Violations.” Fraud detectives, the slideshow said, should look out for “unique stamps” accompanying mail-in ballots. The example given was a 2004 stamp with the words “Test Early for Sickle Cell” over a picture of a Black woman kissing an infant. (Sickle cell anemia is disproportionately common among those of African ancestry.)

A half decade later, in 2010, Abbott’s office sent armed agents to confiscate the equipment and paperwork of a voter registration drive in Harris County called Houston Votes, then the target of a local tea party group, which accused Houston Votes of perpetuating voter fraud. Houston Votes suffocated, unable to raise funds while under investigation. Though Abbott’s office quietly concluded that the group had broken no rules, it destroyed everything it had confiscated, in an episode that would not have been out of place in Belarus.

On the other side of the spectrum, you have the “calculator” school of voter suppression, whose adoptees don’t try to bar voters from casting ballots with the threat of force but rather change rules and tweak the way elections are conducted in ways that give themselves advantages that accumulate. Some of these rule changes are large and easily recognizable, as when elected officials draw districts in ways that favor their party. But many tweaks are small, and their impact can be hard to define or easy to dismiss, not least because they come with the perfectly sensible-sounding justification of promoting election security. (Never mind that Republicans who raise alarms about such security, often by hyping simple clerical errors, have never presented evidence, including in court cases, that it’s a significant problem.)

The key to this strategy is that the constituencies of the Democratic party—the young, the working class, racial minorities—are, generally speaking, harder to register and to turn out to vote. So rules that make it just a little harder and more inconvenient to cast a ballot can usually be counted on to benefit the Republican party. The “calculator” vote suppressors enact laws such as voter ID and changes to the election code, which make lines longer at polling places. They might, say, gum up the postal system so that fewer mail-in ballots are delivered in time to be counted—as President Trump has stated he is working to do, or tighten rules that allow elections clerks to throw out more mail-in ballots from those who didn’t follow an arcane and unnecessary set of rules, as in the case of Gloria Meeks.

Changes like these might not make the difference in a high-profile statewide race, but they have potentially enormous impacts on smaller ones, including elections for the state House, which can be decided by dozens of votes. It’s the state House that Republican leaders like Abbott care the most about right now. They’re laser-focused on it. In 2018 Democrats won 67 seats in the Lege’s lower body. They need 9 more to win the majority this year, giving them some influence over the redistricting process and the drawing of legislative districts.

Democrats may well win a majority with 76 or 77 seats, which means there’s a huge incentive to pull just 1 or 2 seats over into the R column. In 2018 fourteen state House races were decided by margins of fewer than 5 percentage points. Two state House races in Harris County were decided by a margin of 0.2 percent or less: Republican Dwayne Bohac won reelection by 72 votes, and Democrat Gina Calanni beat a Republican incumbent by 97 votes.

Calanni lives in Katy, which is on the western border of Harris County. Because of Abbott’s order, there is now only one ballot collection place in the county, at NRG Stadium, which is a 45-minute drive from parts of Katy in clear traffic—of course a rare sight in Houston. That means some of Calanni’s constituents now face a drive of one and a half hours to turn in a mail-in ballot to the proper officials if they don’t want to give it to a postal service that has been intentionally slowed down by political appointees favorable to the president.

It’s easy to imagine a couple dozen Harris County residents putting off the drive until it’s too late. Maybe they drop their ballot in the mail instead, and maybe they miss that deadline too. It’s likewise easy to imagine that the margin of Calanni’s reelection, or loss, is a few dozen votes. And when you add the impact of Abbott’s order to the many other small ways state leaders have fought to make voting harder than it needs to be in this state—and add to that the impact of the general sense of confusion and demoralization that many Texans feel about the integrity of the Democratic process—you have considerably more than a few dozen votes.

Republicans have done this kind of “calculator” vote suppression for many years, including those in which they were far ahead in the polls and didn’t need the help at all. But this year, the incentive to peel away Democratic margins a few dozen votes at a time is much higher. And with weeks left before the election, it’s safe to assume there are more changes coming.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Greg Abbott