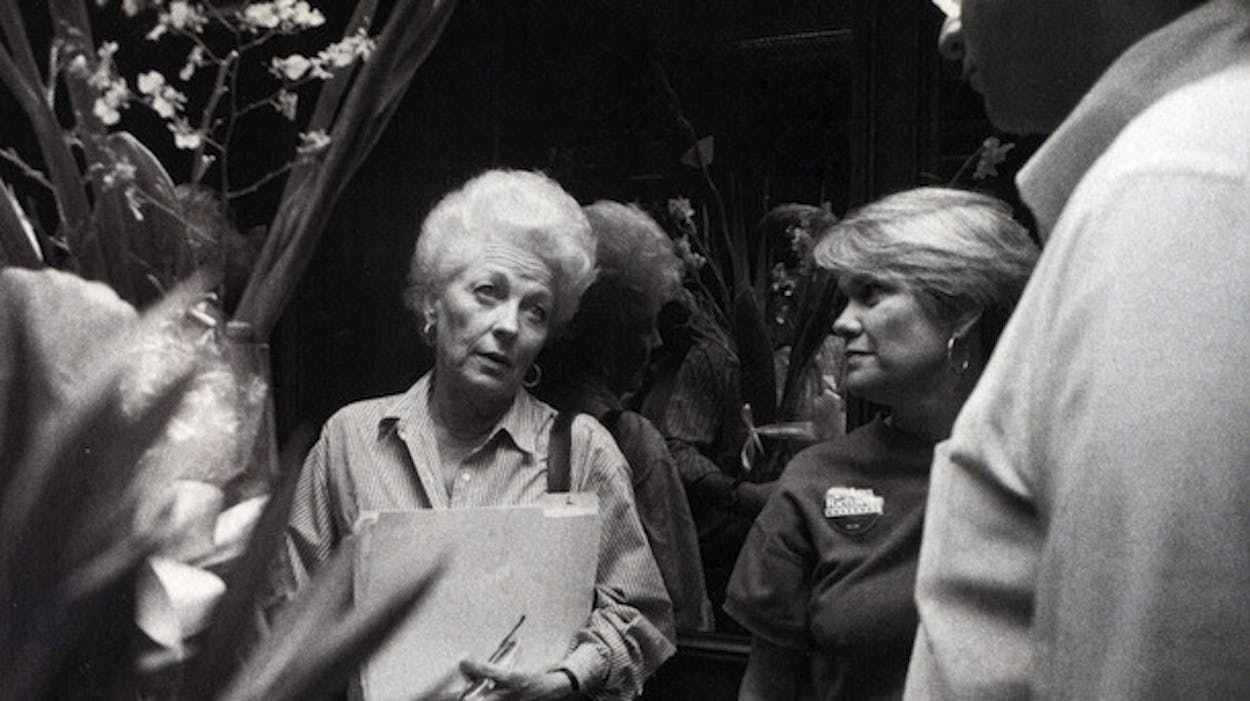

The first time I saw Ann Richards she was playing bridge with old friends at the home of Fletcher and Libby Boone in the hills overlooking Austin. With kids whooping in the bedrooms, a half-dozen card games uproarious in the living room, and much strong drink poured in the kitchen, I was parked on a sofa. I had been invited to the Sunday night tradition because I was courting Dorothy Browne, one of Ann’s old friends and, later, her devoted and trusted aide in state government. It was a hard crowd to overshadow, but that never daunted Ann. She was 47 then, a Travis County commissioner. She was a very attractive woman; for all the premature facial lines and a hairstyle that harked back to a time when “permanent” was used as a noun, sexiness was a distinct part of her bearing. When she turned it on, she was all blue eyes and dimples.

She cocked an eyebrow at the dubious prospects of the hand she’d been dealt, leaned back in her chair, and said, “I’ve just got to tell you all about club,” stretching one syllable into three. “We have such a good time at club. We just talk and talk. And when we get to the end, we vote on what’ll be our next topic of discussion. I think I’m going to propose vaginal itch.”

The bawdy and rowdy feminist was a well-known side of Ann. But something else underlay her crack about the stuffiness and pretensions of social clubs. In a crowd that was well juiced and thought nothing of it, she was talking about the newness and rawness of her commitment to Alcoholics Anonymous. A few Sundays before, her family and close friends had, with great pain of their own, reduced her to sobs in the ordeal of intervention. She walked into a house in West Lake Hills, and on seeing them all, she responded with the instinctive fright of a mother: “Are the children all right?” Hours later she was on a plane to a treatment hospital in Minneapolis. She later said she’d tried to fight off their pleas and their harsh evidence of what she was doing to herself, and to them, because she thought that if she quit drinking, she’d lose her gift for being funny.

“I was terrified,” she wrote of the trip to Minneapolis in her first book, Straight From the Heart. “I was a public person, there was no way I could survive it.” Ann’s long marriage to David Richards, a labor and civil rights lawyer who was also our friend and still is, came to an end in the same period. When Dorothy and I married, in 1982, we invited Ann to our wedding on Fletcher and Libby’s lawn. She sent us a nice gift and a poignant note. She wished us all the best, she wrote, but weddings were something she was having a hard time handling right then.

Ann was wounded in spirit. By standards she held dear—as a wife, as a mother, as a responsible person—she had reason to feel like crawling under a rock. But that was not her way of doing business. Those months at the start of the eighties were the very time when she began a leap upward in politics that would make her grin, drawl, and grit celebrated throughout the world.

Ann was an omnipresent figure in the lives of her friends. She seemed to have been everywhere, seen and done it all, which made her impatient with those of us who were trying to keep up. She was born in 1933, one of the darkest years of the Depression, in a rural community north of Waco. Her dad called on area drugstores, delivering pharmaceuticals, for a salary of $100 a month. She went to Waco High, where she narrowly lost a state contest in debate and met David at an A&W Root Beer stand. After they married and graduated from Baylor University, he went to law school and she began teaching social studies at twenty in a boisterous South Austin junior high. They were standouts in the Scholz Garten gang of liberals. At thirty, living in Dallas, she was a homemaker and political activist awaiting a luncheon speech by the president when it was announced that he’d been shot in a motorcade downtown.

Back in Austin six years later, she carried on her political activism with friends who attended her Episcopal church in West Lake Hills. Other friends, the writers Bud Shrake and Gary Cartwright, embarked on the fabled zaniness of Mad Dog Inc. and a would-be acrobatic act, the Flying Punzars. (The third Punzar was singer Jerry Jeff Walker. Look at the photos on the album cover of Jerry Jeff’s storied ¡Viva Terlingua!, recorded in Luckenbach in 1973. Ann sits on a picnic table, taking it all in.)

Like all successful politicians, she was an opportunist with a run of good luck. Seasoned by working for local candidates like Sarah Weddington, who was elected to the Legislature after arguing Roe v. Wade before the Supreme Court, Ann ousted an incumbent on the Travis County Commissioners’ Court in 1976. She was good at shaking hands and promising to keep folks’ roads fixed. There was a prickly edge to her feminism, but her articulation of those views had an old-fashioned quality that resonated in Texas. “I know there are exceptions,” she later wrote, “and that there are men who do the laundry and who go to the grocery store and plan the meals. But most of the men I know go to the grocery store with a list of instructions. And that list is put together by the female of the household. Men drive the car pool or pick up the cleaning because they are told to. … So, if a woman is not there, the whole management of the house suffers.”

By the time Dorothy and I married, Ann was sober and single, though she and David called it a separation for two more years, and she had defeated an incumbent Democratic state treasurer who had been indicted for misusing his office. At the treasury Ann found employees trundling numbers on obsolete calculators and undeposited checks to the state gathering dust on desks. She was no banker or computer programmer, but she hired some, and she set about managing the state’s money.

Ann also had the antiquated authority to commission and pin old-style badges on treasury agents and other peace officers. As the state’s top tax collector, Comptroller Bob Bullock—Ann’s mercurial drinking buddy and shrewd political mentor—decided he wanted such a badge; he pestered her for it, and he never took kindly to anyone turning him down. Well-known for his love of firearms, Bullock was rumored to have once stuck a pistol in the ear of an offending driver of a New York taxi in which he and Ann were passengers. “I can’t commission him as a peace officer and license him to carry a gun,” she said with an exasperated laugh. “He’d be dangerous.” (Bullock decided soon after Ann that he too had better sober up.)

For several years Dorothy had been the assistant director of the Texas office of the American Civil Liberties Union. She burned out and took a few months off, and in the course of her 1985 job hunt, she wrote Ann a shy and tentative letter of interest, telling her old friend that she didn’t really know what the treasury did or what she could offer. “Dorothy, come over here!” Ann commanded on the phone. When Dorothy arrived, she told her, “You can do anything you set your mind to.”

Her job entailed research of myriad issues and knowing the names and personalities of political associates who expected to be recognized, and she drafted correspondence for Ann in a style reasonably close to her voice. Ann liked to work in her stocking feet. At night, when most of the staff had gone home, Dorothy often heard the sound of her padding down the hall, a letter in her hand. Our daughter, Lila, recalls Dorothy marveling that Ann would be talking about policy while pulling out a needle and thread and stitching up a runner in her pantyhose.

It’s never been clear how Ann got to make the keynote speech at the 1988 Democratic National Convention—she was as surprised as anyone. When she got the chance, she hit a home run, though the speech tailed off when she made it to the part about the ticket, Michael Dukakis and Lloyd Bentsen. The lines—about George H. W. Bush’s silver foot, Ginger Rogers’s dancing backward in high heels, Ann’s game of ball with her grandchild Lily—were matched by the beauty of her, all silver and blue, and the sheer joy of her timing and delivery. She went onstage a little-known state politician and walked off a television superstar.

In the 1990 race for governor, the attorney general, Jim Mattox, expected to win the Democratic nomination with ease—until Ann’s catapulting speech. Her campaign staff came up with the idea of launching the campaign with a tour of the Gulf Coast on a chartered yacht. At each stop the craft would pick up and drop off experts in public and private sectors of the varied locales, and they would brief Ann. She wanted some friends onboard who were not these experts, her campaign staff, or the press. I had been writing speeches and position papers about coastal issues for Garry Mauro, then land commissioner. Dorothy took a week’s vacation from the treasury, and we flew down to Corpus to catch the boat.

The plan at first seemed brilliant. Local TV crews swarmed; on a beautiful day dolphins sported in the wake as the boat cruised into the bay. Ann kept the briefings concise, on subject, and never seemed to lose concentration or interest. As the craft skated on the narrow Intracoastal Waterway past barges posted with skulls and crossbones—cargoes of toxic chemicals—we learned about refineries and beach erosion and how a healthy diet of shrimp brightens the pink plumage of roseate spoonbills. The state’s top political reporters were onboard for the duration, and by the first afternoon their eyes were starting to glaze over. They were cracking jokes with their competitors, editors at their papers were dogging them to file, and there was no story.

The second afternoon we noticed them trying to get some privacy. They had shoe phones in those days, and on breaks between briefings they spread out and leaned over the rails, speaking quietly. “There’s something wrong with the boat,” one was heard to murmur. It turned out that the owner of the yacht, a dapper gentleman who was clearly entranced by the media and the air of celebrity, and his son, who was actually manning the wheel, did not have licenses and therefore could not legally operate the boat. That night in our cabin, as the boat rocked slightly in a slip at Port Lavaca, Dorothy and I witnessed a campaign staff in total jabbering panic. Phone calls flew back and forth. The Mattox people were all over this, they claimed; what if the captain was arrested? Late that night a young man announced that we were all jumping ship. The newborn Richards campaign was going to chug up the Houston Ship Channel the next day on a shrimp boat with no air-conditioning. While we slept on this prospect, cooler heads decided that the owner and his son would leave the boat and the tour would continue with the crew’s first mate, who was properly licensed, at the helm. The sun was not yet up when Ann summoned me for my counsel. “I just feel bad about the old man,” I offered.

“What?” she said.

“Well, he’s been enjoying this, and it is his boat.”

The set of her mouth let me know that in politics I was a total amateur. Here I was, sentimentalizing over the man, who was being well paid for providing that charter, as if he were a child with hurt feelings. “Jan,” she said. “I didn’t take him to raise.”

By the end of that primary, in which Mattox and then the press hounded her to admit past drug use, Ann was so far behind Clayton Williams, the rich West Texas Republican, that the November race seemed hopeless. She called in Mary Beth Rogers, her deputy treasurer, to replace “the guys”—Glenn Smith and Mark McKinnon—who had been managing her campaign. Then Ann’s luck kicked in. Among other blunders, Williams cracked a joke about rape, predicted in cowpoke terms that he was going to rope her like a heifer, and refused to shake her hand. Appalled women in the suburbs couldn’t wait to get to the polls; Ann was the beneficiary of one of the most spectacular self-destructions in Texas political history. On a blustery January morning in 1991, she led an energetic multiethnic throng down Congress Avenue to take back government. I remember glancing above the sidewalk at windows in the office buildings. White guys in suits were looking down smiling, charmed by the spectacle, inclined to give her a chance.

Ann made reform of insurance and ethics guidelines early priorities of her administration, but she is best remembered for sending shock waves through the agencies and commissions with her appointments of women, Hispanics, and blacks. She and Mary Beth brought Dorothy with them from treasury and named her the assistant director of the criminal justice division. They wanted someone who would keep a close tab on the millions of federal dollars flowing through their hands. They also liked jacking with the minds of ex-cops and wardens, who would read Dorothy’s résumé and see the words “American Civil Liberties Union.” Later, Ann put her in charge of building from scratch the country’s most ambitious program of drug and alcohol abuse treatment in the prisons. Texas shot from fiftieth to first in number of beds in a matter of months, though the program has since been scaled far back. Initially skeptical, to put it mildly, several of those wardens are still Dorothy’s good friends.

Ann’s escort to her inauguration was the onetime Flying Punzar Bud Shrake. They went steady, as she put it, for the rest of her life. We’d see the governor and Bud holding cups of popcorn at Sunday matinees among moviegoers who were astonished it was really her. “How’re you?” she’d greet the ones who came up, and they seemed to believe their answers mattered.

Less dazzled were conservative legislators and the press, which hardly gave her a free pass. One time, as part of her Smart Jobs economic development initiative, she led the Capitol press corps to an East Texas factory where laid-off workers were being retrained as welders. A stifling day was made hotter by the welding torches. At the press event that followed, a TV reporter named Jim Moore, who seldom let up on any politician, cracked, “If welding is a smart job, what’s a dumb one?” She let him go on sweating under his boom mike for a moment and then smiled. “You know, Jim, it don’t look to me like it takes a lot of smarts to be a microphone holder.” (Just the same, on receiving a letter from the young daughter of that constant adversary, Ann carried on a warm and encouraging correspondence with the girl that lasted through her college years.)

In governing, Ann tried to veil the fact that she was a liberal, and in chasing the center she sometimes looked awkward, even inept. Though no one questioned the hours she put in or her commitment to the ideal of public service, throughout her 1994 race against George W. Bush her own internal polls told her that this time she had just 47 percent of the vote. The national press cast Bush as the underdog, but I had a sinking feeling when Dorothy and I attended her reelection campaign kickoff in Austin. It was her birthday, Jimmie Dale Gilmore performed, and she made a fiery speech. But the event didn’t have a pulse.

Ann acknowledged that she ran a poor campaign in a year that saw a nationwide GOP sweep, but she believed her loss came down to one principle she refused to compromise. A clamor had arisen to allow citizens to carry concealed handguns. With strong backing from law enforcement she vetoed the Legislature’s bill in 1993, but the issue wouldn’t go away. The National Rifle Association and the Bush campaign used it deftly. She must have gotten tired of hearing about pistol-packing Texans, and one night on the trail she lost patience—some would say discipline—in her inimitable fashion. She wouldn’t mind so much, she said, if these trained shooters were required to hook their pistols to chains around their necks. That way others could say, “Look out, that one’s got a gun.” She thought the issue and her stand cost her the election.

Dorothy works at the Legislature now. In March Ann called and said, “I’ve got a young woman here who doesn’t know what she wants to do with her life.” The ex-governor served with the woman’s father on the “car wash board” and wondered if Dorothy might help her find an internship at the Capitol. Recalling how her own involvement in government began, Dorothy said she would gladly try (the young woman eventually joined the House staff of Dorothy’s boss, Elliott Naishtat). Dorothy then asked her mentor how she was doing. “Not so good,” Ann replied. It was one of the only times her voice sounded small. Ann said that the day before, she had been diagnosed with esophageal cancer. She sounded frightened; who wouldn’t be?

At her memorial in Austin in September, Hillary Clinton observed that right after September 11, when so many Americans were inclined to put distance between themselves and New York, Ann chose to join the Public Strategies consulting firm and live in Manhattan. People would call out her name and come up to shake her hand just as they did in Texas. That’s the image I dwell on now, not the bouquets of yellow roses in the rotunda of our Capitol. I can see her strapping her purse over her shoulder—having no harried young male aides to lug it around, as she did when she was governor—and barging up those sidewalks grinning, proud of her good heart and thrilled by the journey.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Ann Richards