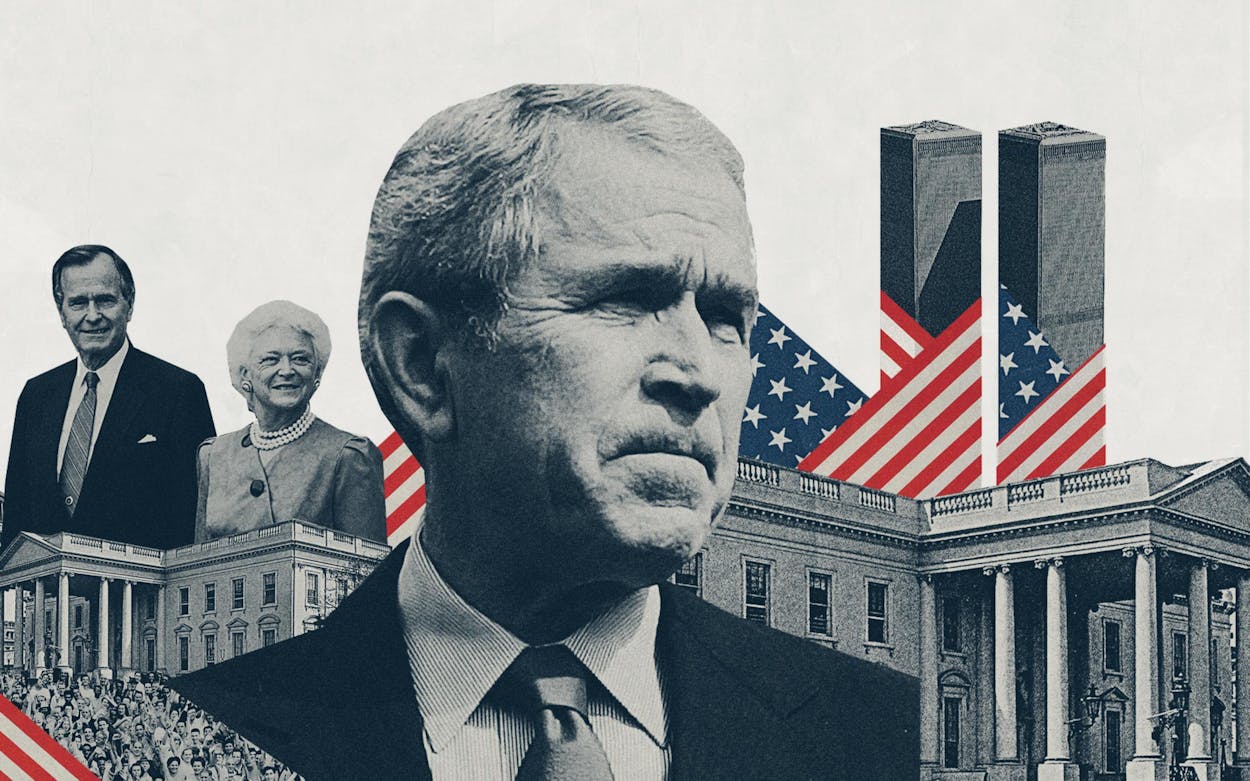

The George W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum opened seven years ago and anchors the southeastern corner of campus at Southern Methodist University, where I teach history. In late November 2016, I took a tour of the facility with five college friends who were visiting from the East Coast. The recent presidential election was much on our minds as we wandered through the building, contemplating various artifacts from Bush’s two terms in office. Although we were hardly fans of his presidency, one of my pals—fearful, like everyone in our group, of a Trump administration—got misty-eyed when reflecting upon Bush’s obvious love of country. After an hour or so, with a requisite stop for photos in the museum’s full-sized and perfectly appointed replica of the Oval Office, we left in glum moods.

As was the case with my friends and me, the chaos of the past few years has caused some of Bush’s detractors to revise their assessment of W and his legacy. Princeton historian Sean Wilentz, for instance, no longer regards him as the most likely modern contender for the worst president in U.S. history. Former Senate majority leader Harry Reid, a onetime Bush adversary, confessed to a journalist earlier this year that he often finds himself thinking, “ ‘Boy, I wish Bush were here now.’ . . . He was a patriot. I disagreed with him. But he was somebody you could talk to, joke with, had a good personality.” And many noted the heartfelt decency that Bush demonstrated during his brief but moving remarks at the recent funeral for Congressman John Lewis—who had declined to attend Bush’s inauguration in protest over the contested 2000 election.

Donald J. Trump’s calamitous administration has provided the Bush family with an opportunity to capitalize on this budding nostalgia. A pair of recent books by W’s late mother and his daughter reassert the clan’s reputation for graciousness and public service, implicitly suggesting that George W. Bush, the most prominent living member of the family, should be regarded as an heir to that ethos. But this effort at reestablishing a once-cherished brand has not gone uncontested. Two other volumes as well as a recent PBS documentary have insisted on reminding us of W’s grievous limitations and failures, offering evidence of why he left office as one of the most unpopular presidents of the contemporary era.

At the same time, the family has, in the political sphere, struggled to make the case for its continued relevance, which arguably reached its zenith during the presidency of W’s father. The relatively centrist George H. W. Bush was a skilled executive who ably oversaw the fall of the Soviet empire, acted decisively in defense of Kuwait against Saddam Hussein’s invasion, and saw through substantive domestic policies like a cleanup of the savings and loan crisis and comprehensive immigration reform. (This era of comparative consensus is vividly evoked in Susan Glasser and Peter Baker’s The Man Who Ran Washington: The Life and Times of James A. Baker III, an excerpt of which accompanies this review.)

Today, however, the Bush family’s political profile has all but bottomed out: Jeb Bush disappeared from the public eye shortly after his disastrous 2016 run for the White House. George P. Bush has hardly set the world on fire as land commissioner of Texas. And this past spring the largely unknown Pierce Bush made a bid for a suburban Houston congressional seat in a manner that was so bereft of gravitas or purpose that one couldn’t help but wonder if the family is in danger of turning into a parody of itself. In short, rehabilitating the Bush family trademark may be a mission not so easily accomplished.

What some miss most about the forty-third president, it seems, is his decorum. George W. Bush came by it honestly, given the WASP-y New England milieu into which he was born and which his parents brought with them when they moved to Midland during W’s boyhood. The Bushes have long projected an aura of noblesse oblige, off-putting, perhaps, in its snobbish belief that the “right” people should make decisions for the rest of us, but rooted nonetheless in a sincere commitment to good works. Pearls of Wisdom: Little Pieces of Advice (That Go a Long Way) (Twelve Books) lists the late Barbara Bush as its author but was assembled by Jean Becker, who served as Mrs. Bush’s deputy press secretary and then as Bush père’s chief of staff during his post-presidency. It tidily encapsulates this fading blue-blood ethos, showcasing both its laudable and its lamentable attributes.

Much of the book is lighthearted, especially those maxims governing the management of younger generations. On driving: “Don’t lend your car to anyone you gave birth to or their offspring.” On teenagers: “Be careful of criticizing their clothes. What they change into could be tighter and shorter than what you made them take off.” But the core principles in Pearls of Wisdom foreground the genteel restraint that Mrs. Bush sought to inculcate in her progeny. In this sense, it reads at times like a stinging rebuke of Donald Trump. On wealth: “Don’t talk about money—either having it or not having it. It is embarrassing for others and quite frankly vulgar.” On civility: “Don’t brag. Don’t toot your own horn too loud. Don’t talk like a big shot.” On friendship: “The most important yardstick of your success will be how you treat other people.” It seems unlikely that Fred and Mary Anne Trump showered their brood with similar aphorisms.

Despite its modest appeal, Pearls of Wisdom may alienate some. In the first place, the Silver Fox often took a cavalier approach to following her own advice. Many readers will recall that she was famous for her acid tongue. (During the 1984 presidential campaign, she made headlines when she said that she couldn’t publicly voice her characterization of her husband’s vice-presidential opponent, Geraldine Ferraro, offering coyly that it “rhymes with ‘rich.’ ”) And at times she seems blind to her extraordinary privilege, as with her dictum (so dear to her that it’s rendered in all capital letters): “DO NOT BUY SOMETHING YOU CANNOT AFFORD.” While the message may be apt for those of prosperous means, many Americans often have no choice but to buy necessities that plunge them into debt.

The core principles in 'Pearls of Wisdom' foreground the genteel restraint that Mrs. Bush sought to inculcate in her progeny. In this sense, it reads at times like a stinging rebuke of Donald Trump.

There is, though, no doubting the powerful example Barbara Bush set for her descendants. Consider Everything Beautiful in Its Time: Seasons of Love and Loss (William Morrow), her granddaughter Jenna Bush Hager’s reflections on losing her three surviving grandparents in the short span between April 2018 and May 2019. While the cover is a wistful, sunlit photo of her and her grandfather George H. W. Bush, the book focuses most intently on Hager’s relationship with Barbara Bush. A clear measure of the indelible imprint left by her “Ganny” emerges poignantly in a letter Hager drafted after her grandmother’s death. “We called you the ‘enforcer,’ ” she writes. “It was because, of course, you were a force and you made the rules clear. Your rules: treat everyone equally, don’t look down on anyone, use your voices for good, read all the great books.”

But just as she perfectly distills the WASP code that seems braided into the Bush family DNA, Hager—like her beloved grandmother—appears at times oblivious to the fact that people less cosseted than she (that is, almost everyone) may find it difficult to draw personal meaning from her experiences. In an early chapter, Hager—who serves as a cohost of NBC’s Today With Hoda & Jenna and has published four previous books—confesses her embarrassment when her screaming toddler draws unwanted attention on a Manhattan sidewalk to “the little girl’s elegant grandmother, the former First Lady [Laura Bush], in her neat sweater set.” Even when describing her mortification, Hager feels compelled to point out how well-appointed her mother was at the time.

Nevertheless, amid Hager’s lapses in self-awareness—to say nothing of the book’s treacle and cliché—readers of Everything Beautiful in Its Time will spot some of the same Bush politesse that even now bolsters Dubya’s reputation. Most telling might be the letter Hager and her sister left for Sasha and Malia Obama during the transition between their fathers’ administrations in January 2009. Their note—imploring the newcomers “to remember who your dad really is” in the face of the brutal media caricatures sure to come—calls to mind the gracious missive their grandfather penned to Bill Clinton after Poppy’s painful loss in 1992, continuing a tradition that W himself honored sixteen years later, and one that may be endangered come January 2021.

But whatever longing one might feel for George W. Bush the human being may quickly dissipate upon revisiting the most significant legacies of his administration, beginning with W’s fateful decision to invade Iraq in 2003. In To Start a War: How the Bush Administration Took America Into Iraq (Penguin Press), Texas-born journalist Robert Draper—a writer at large for the New York Times Magazine and a contributing editor to Texas Monthly—seeks to understand why, less than two years after 9/11, the U.S. military attacked “a sovereign nation that had neither harmed the United States nor threatened to do so.” Armed with this simple question, Draper interviewed dozens of officials throughout the government, receiving particular assistance “from those operating in the middle tiers—the actual doers who were in a position to know a great deal but who do not have legacies to protect.” (One subject with whom he did not speak was the former president himself, who was displeased with Dead Certain, Draper’s 2007 book about W’s administration.)

Draper’s conclusion is succinct and maddening: because Bush’s closest advisers mistakenly thought that the president had already settled on a showdown with Saddam Hussein, they supplied him with counsel that buttressed the decision they believed he had already made—and ended up convincing Bush that he had no other choice but to press forward. Among the findings supporting this view is the author’s discovery that there were a number of individuals within the intelligence community who considered the evidence against Hussein at once under-sourced and oversold. And yet such concerns were muffled by their superiors, who thought—as Draper explained in a recent episode of the Intelligence Matters podcast—that war was inevitable and didn’t want to be “on the bad side bureaucratically of what would have been a losing argument.”

The tragic outcome was arguably the most disastrous U.S. foreign policy decision in the nation’s history. Coverage of the Iraq War devours nearly a quarter of the two-part, four-hour George W. Bush, an installment in the PBS American Experience documentary series that debuted in May (and is now available for streaming on Apple TV and Amazon Prime). Few, if any, two-term presidencies of the modern era seem quite so easily reduced to a single narrative thread, and unfortunately for Bush’s would-be redeemers, not many of the film’s talking heads have much to offer in defense of Operation Iraqi Freedom. More representative of the documentary’s take on the war is the stern judgment offered by the Pulitzer Prize–winning columnist Eugene Robinson. In reflecting on the invasion of Iraq and the grotesque excesses of the larger War on Terror, Robinson says wistfully that after 9/11 Bush “had a measure of support that no president could ever dream of. And in a sense he squandered it.”

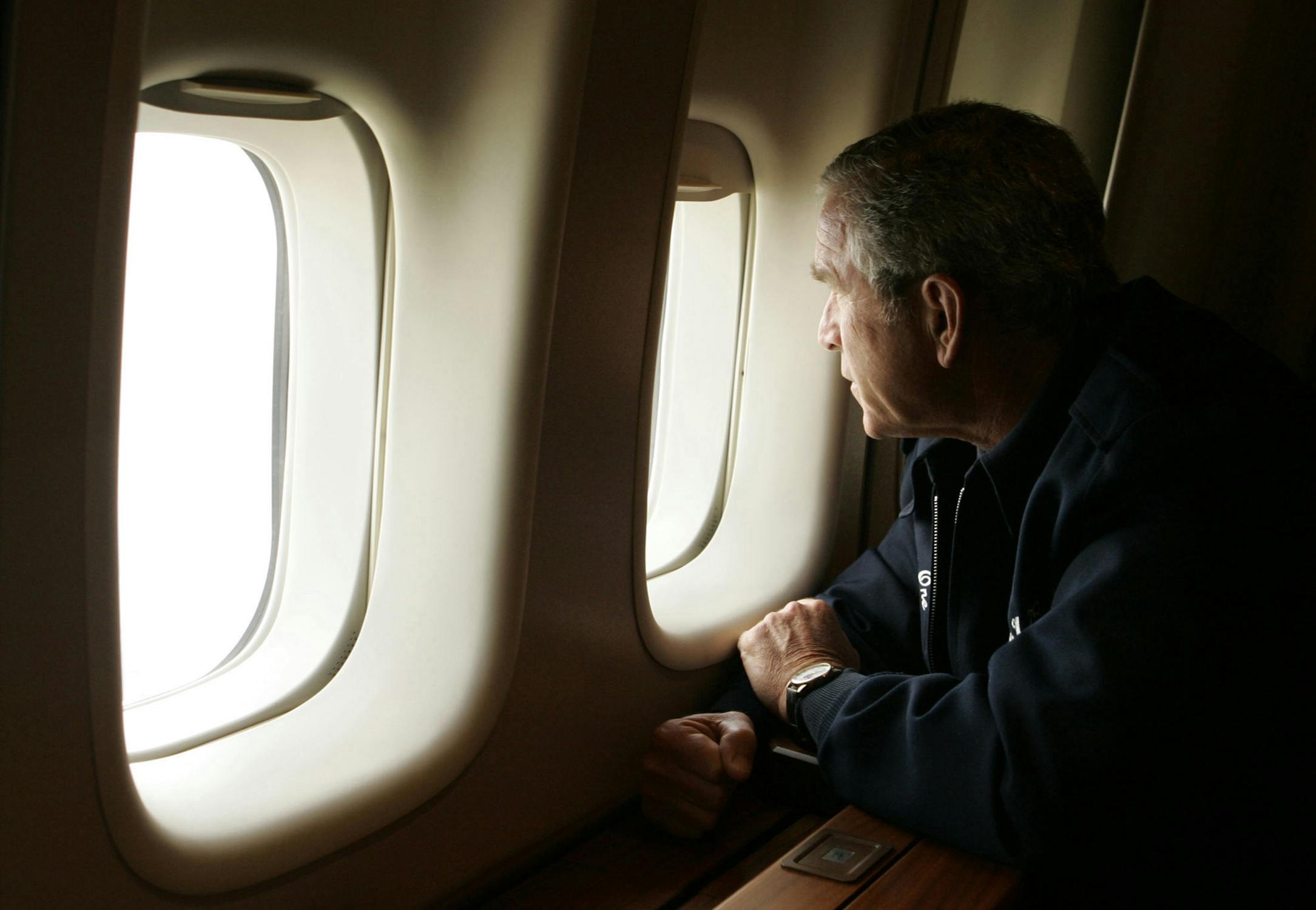

Still, the film argues, W came to view his bungled response to Hurricane Katrina as even worse for his presidency than the failures in Iraq. On August 31, 2005, two days after the levees protecting New Orleans failed, Bush managed only a 35-minute, low-altitude flyover on the way back to Washington, D.C., from his ranch in Crawford. He appeared to many Americans as out of touch and uncaring, a point conceded on camera even by his oleaginous counselor Dan Bartlett. Worse, federal aid to Louisiana and the Gulf Coast was delayed for days. Journalist and author Ron Suskind, one of the more perceptive voices in the film, sees the twin fiascoes of 43’s presidency linked in indelible ways. “Katrina ends up being an immediate domestic version of Iraq,” he says. “Bad planning, warnings that Bush doesn’t heed, people in various positions who don’t do their job the way any president would want them to, and all of it comes a cropper with Katrina.”

Concerns that the evidence against Saddam was under-sourced were muffled by people who thought war was inevitable and didn’t want to be on the bad side of a losing argument.

This fleeting but trenchant observation lies at the very heart of Landfall (Vintage), Thomas Mallon’s darkly comic novel of the Bush presidency. While the story turns largely on the romantic relationship between a pair of fictional characters ensnared in the administration’s two disasters (as it happens, one of the lovers is a sad sack former SMU history professor), Mallon lards his tale with exquisitely drawn profiles of countless Washington figures. The most resonant of these depictions include Condoleezza Rice (brilliant but obsequious), Donald Rumsfeld (cryptic and despicable), and Mallon’s close friend the late writer Christopher Hitchens (quaffing and caustic). Mallon clearly understands Texas—he lived in Lubbock during Dubya’s unsuccessful run for Congress in 1978—as demonstrated by his on-the-nose sketch of Ann Richards, featured prominently as a Greek chorus who fills in W’s backstory, often in hilarious conversations with the television host Larry King.

Looming over the proceedings, of course, is W himself, to whom Mallon was drawn by the same “aura of mystery” that led him to write a pair of previous novels about Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan. One of the protagonists in Landfall, who has experienced firsthand the devastation of Hurricane Katrina, ruminates on that enigmatic quality after receiving a personal email from Bush midway through the book. “[H]e tried to understand the president—a man he now regarded as a maestro of catastrophe, someone whose sympathy for those suffering might be genuine enough but was too little visceral or sustained to be of use. Could it ever be tethered to fruitful action, or would it always float free, like his hand-written syllables, amiable and testy by turns?” Mallon is munificent in his portrait of Dubya, offering up a version of what seems to be jelling into our consensus view of a man who once sharply divided the country: neither the depraved villain imagined by liberals nor the fearless cowboy treasured by conservatives but, rather, an affable, insecure naïf, woefully inexperienced and tragically incompetent.

At the time of this writing, the George W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum remains temporarily shuttered, thanks to the spectacular mismanagement of a different crisis by another administration. The last time I visited, in spring 2019, I was accompanied by a fellow historian who boasts considerable experience in the museum world. He remarked that even by the standards of other presidential museums, the effort to recast W’s time in office was strikingly brazen, noting especially the near-total absence in the permanent exhibits of controversial figures such as Vice President Dick Cheney. Likewise, the museum gives as much emphasis to 9/11 as it does to the invasion of Iraq—suggesting that the brief moment in which Bush, bullhorn in hand, shone most brightly was as important as the yearslong military debacle that consumed his presidency and continues to define him.

These curatorial choices bothered me less than did a special exhibition that ran for seven months in 2017. “Portraits of Courage” was a collection of several dozen paintings by the former president of men and women who had served in the U.S. military since 9/11. Bush had personally gotten to know each of his subjects, such as Sergeant First Class Scott Adams, who was severely injured in Iraq in 2007, suffering numerous internal injuries, burns over more than 90 percent of his body, and lingering nightmares. Some art critics commended the obvious compassion that permeates these portraits.

I thought about taking in the show myself but never made the trip across SMU’s lush grounds to have a look. For though I had come to recognize that George W. Bush is a likable enough person, “Portraits of Courage” aroused a state of cognitive dissonance in me; I couldn’t reconcile the notion of W celebrating the tremendous sacrifices of these soldiers with the damning fact that he had sent them to war on false pretexts. It seemed akin to an arsonist extolling injured firefighters for putting out a blaze he had set.

As far as most Americans are concerned, the conflagration in the Middle East that Bush touched off has cooled in recent years. But today there are still five thousand troops stationed in Iraq, charged primarily with holding off the reemergence of ISIS, an organization that grew out of the destabilizing effects of Bush’s war. Meanwhile, here at home, another inferno that Dubya helped instigate—the election of Donald J. Trump, who used his disparagement of the Iraq War as a wedge issue in the 2016 campaign—continues to rage.

Andrew R. Graybill is a professor of history and the director of the William P. Clements Center for Southwest Studies at Southern Methodist University.

This article originally appeared in the October 2020 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Miss Him Yet?” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- George W. Bush

- Dallas