Until fairly recently, the politics of criminal justice was a simple matter. Put criminals in jail, as many as possible. Both Democrats and Republicans ran for office on a tough-on-crime platform. But as crime rates plummeted and the toll of mass incarceration became apparent to all but the most hardened lawmakers and prosecutors, political space opened up for criminal justice reform and for more compassionate, evidence-based approaches. In the last few years, there’s been a new development—a strong push from the left to elect reform-minded prosecutors to change the system from inside.

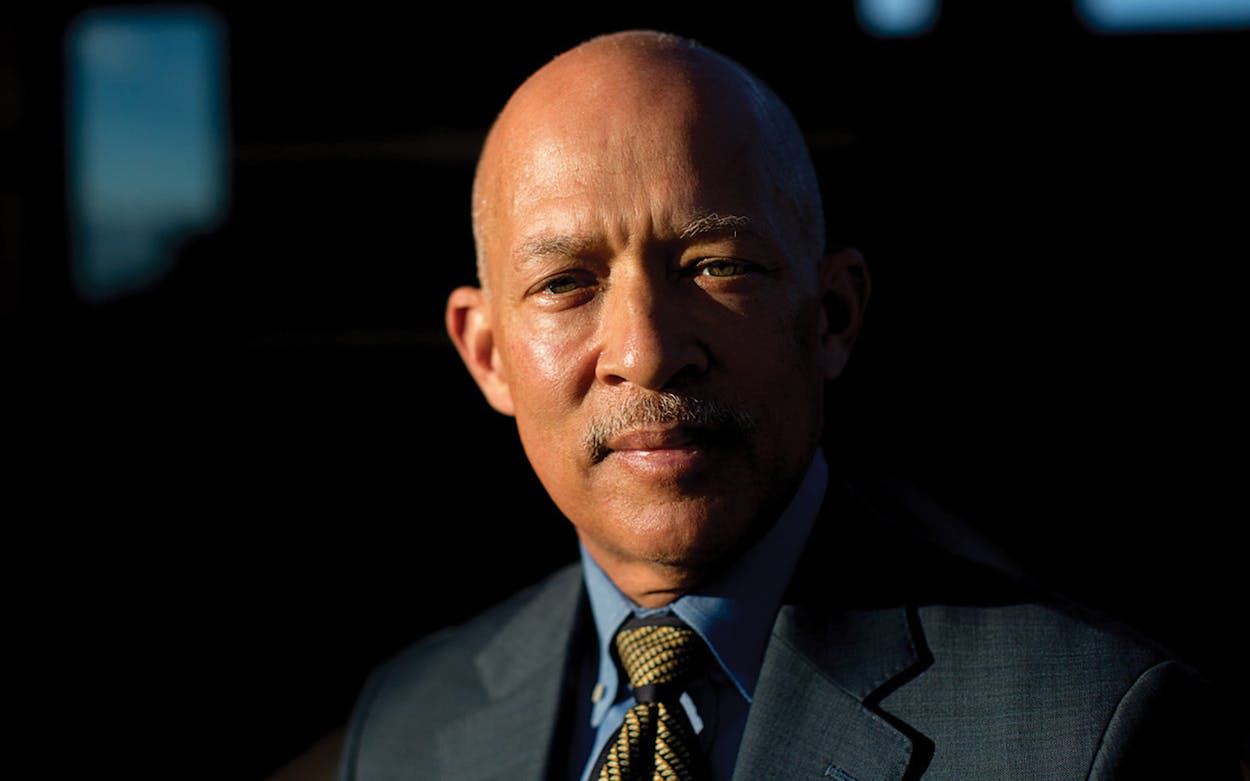

Dallas District Attorney John Creuzot was elected in 2018 as part of that push. In the 1980s he worked under the legendarily tough Dallas DA Henry Wade, who was responsible for the prosecutorial culture featured in the famed Errol Morris documentary The Thin Blue Line. In the late 1990s, Creuzot, by then a district court judge, met then-lieutenant governor Rick Perry’s staff at a convention in Washington, D.C., and helped pitch Perry on the value of drug courts. Under Perry, Texas made sweeping changes to its criminal justice system, closing prisons and diverting nonviolent drug offenders to treatment programs.

Many conservatives in Texas supported the reforms, taking the position that overhauling the criminal justice system was both fiscally sound and in line with a Christian sense of equity. Perry “was our best advocate for reforming criminal justice,” Creuzot said in a 2014 video, and Perry’s push to introduce and expand drug courts “is one of the best things that has happened in the United States.”

Creuzot no longer has a friend in the Governor’s Mansion, as Governor Greg Abbott made abundantly clear last week. On April 11, Creuzot produced an open letter detailing changes he planned to make to how his office handled cases. The list included proposed changes to the bail system and a promise to decline prosecution for certain small-time drug offenses and other petty criminal matters that often involve the poor, mentally ill, and homeless, like misdemeanor criminal trespass charges that don’t involve “a physical intrusion into property.” Those are standard agenda items for reformist DAs.

Tucked in the middle, however, was a declaration that drew outsize attention. Creuzot wrote briefly that when “we convict people for non-violent crimes committed out of necessity, we only prevent that person from gaining the stability necessary to lead a law-abiding life.” As such, he wrote, his office would no longer prosecute cases of theft of “personal items” of less than $750 “unless the evidence shows that the alleged theft was for personal gain.” Call it the Jean Valjean rule.

A firestorm erupted: The Dallas DA, according to his critics, Abbott foremost among them, had legalized theft! Dallas police groups held a press conference to argue that the change was irresponsible and would be harmful to Dallas businesses, and the Combined Law Enforcement Associations of Texas even called for Creuzot’s removal. George Aranda of the National Latino Law Enforcement Organization said the Dallas DA “had opened up many windows to allow the common criminal to feast on the business retail community.”

Governor Greg Abbott tweeted that the change amounted to “wealth redistribution by theft” and “socialism.” “If someone is hungry they can just steal some food. If cold, steal a coat. Where does it end?” Abbott and Attorney General Ken Paxton sent Creuzot an open letter to warn that “reforming’ state law is the province of the Legislature,” adding that “we hope that you reconsider your position,” in what seems like a clear promise to get more involved if Creuzot fails to do so. Even some Democrats in the Legislature opined that the policy had gone too far.

Creuzot rushed to say that he had been misunderstood. At a town hall last Thursday at the Texas Theatre in Dallas, Creuzot told the audience that his open letter “was not worded as well as it should have been.” The change in instructions only applied to “a person [who] is poor and hungry and is stealing to eat, to sustain themselves.” Arresting needy people for petty theft puts them in a position “where it’s harder to get a job, harder to get a normal life,” and that increases the likelihood they commit more crime, he said. All other thieves—those who steal for fun or to resell goods—would still be eligible for prosecution.

The sometimes rowdy town hall was held by the Texas Organizing Project, a grassroots community organizing group that helped elect Creuzot. Dozens of people lined up to ask questions, which ranged from inquiries about the policy change to accusations—from people who had been sentenced in Creuzot’s old court—that he had railroaded them. Not long ago, this kind of town hall would have been unthinkable; prosecutors cared a lot more about the support of the police union than the general public. The town hall was part of a campaign to show the DA he had support to deliver on reforms, explained TOP deputy director Brianna Brown.

But in truth, the policy change seems unlikely to be nearly as consequential as the outrage would suggest. Petty theft is a huge problem for retailers, but not one that typically involves prosecutors. According to an article last year in the Columbia Law Review, major retailers have largely privatized their response. Rather than calling the cops, chains like Walmart have started handing offenders to controversial private companies that offer to keep the police out of the matter if the accused pays a fee.

What’s more, though information about shoplifters is hard to come by, research suggests that two-thirds of shoplifters are under the age of 15, and one study found that those with a college education were more likely to shoplift than those in poverty, which would seem to indicate that a small percentage of offenders are likely to meet Creuzot’s criteria for non-prosecution. It’s also not clear whether prosecutors, who have heavy workloads, were ever zealously prosecuting these kind of steal-to-eat cases.

Some critics say Creuzot shouldn’t announce that he won’t prosecute certain crimes at all, on the theory that doing so invites criminals to do more crime. A prosecutor, the thinking goes, should act like Inspector Javert even if he isn’t. Regardless, the reaction to Creuzot’s reforms seems out of proportion to what he was proposing.

The true significance of this fight may be as a sign of how the politics of criminal justice are changing yet again, at least in Texas. The conservative “right on crime” coalition that drove reform over the last decade pushed for policies that had bipartisan appeal, and as a Republican in good standing, Perry had the ability to go “soft” on crime without taking political heat for it. (Some members of that coalition have offered support for Creuzot, while others have been quiet.)

But the efforts to enact reform through DAs is taking place in the state’s blue cities, where activists are pushing to end mass incarceration. Those new prosecutors, like Mark Gonzalez in Nueces County and Kim Ogg in Harris County, have struggled to figure out how far they can go and how fast, with some playing offense and others defense.

As it happens, messing with blue cities and their elected officials is political catnip for Texas Republicans, and crime is a powerful wedge issue. Ogg was elected with help from George Soros, and Dallas County has long been a source of anxiety for the state GOP. If Creuzot didn’t expect this backlash, he now knows there are a lot of people waiting for him to trip up. Perry’s not around anymore.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Greg Abbott

- Dallas