If you’d only ever read about the SXSW “Homeless Hotspots” program when the news first broke on Twitter (via the New York Times‘ Tumblr) Sunday, you would have thought that it was dreamed up by a giant corporation, which sent its minions around Austin loading vagrants onto flatbed trucks, who were then surgically implanted with 4G Internet devices and forced to stand outside the Austin Convention Center wearing t-shirts that said, “I am a 4G hotspot.”

Only the t-shirt part was true.

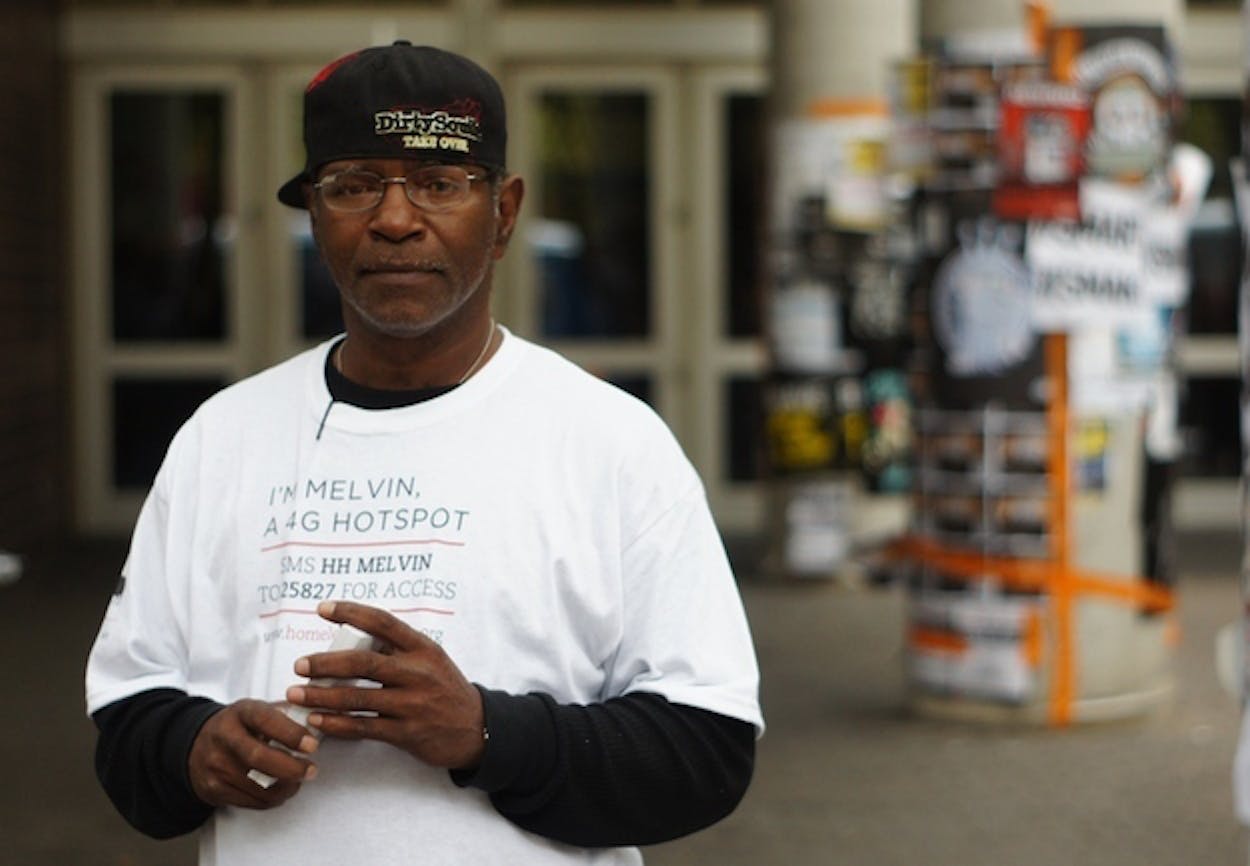

Dubbed a “charitable experiment at SXSWi” by the New York-based “Labs” division of the marketing and advertising company BBH (Bartle Bogle Hegarty), “Homeless Hotspots” employed ten homeless Austinites to set up outside of the convention center with portable 4G devices from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., charging $2 (via PayPal or the mobile site itself) for fifteen minutes of Internet access.

Decried as exploitive or dehumanizing, it became “Sunday’s most talked about SXSW story,” according to John Herrmann of Buzzfeed, and it has remained so for the past few days.

But even though a great deal of the indignant coverage blasted BBH, it seems as though the old “there’s no such thing as bad publicity” maxim applies. Now that the program’s over, the Austin homeless services organization Front Steps, which connected BBH with its clients, has pronounced it a success.

“We are all so grateful we had this opportunity,” says Front Steps director of development and communications Mitchell Gibbs. “Overall our community is hearing a whole lot more about homelessness then maybe (it) would have otherwise, and we’re having the conversation on a national scale that we didn’t anticipate being fortunate enough to have a few days ago.”

A good deal of the coverage was devoted to questions about how much money BBH’s volunteers could actually make. All the proceeds are supposed to go to them, but nobody was sure how much that would be. They received an up-front $20 stipend each day, and now, BBH’s Saneel Radia has provided semi-concrete numbers on his blog:

These volunteers were guaranteed make at least $50/day, for a maximum of 6 hours work. This amount equates to more than the Texas state minimum wage of $7.25/hr for the same number hours. Based on donations already received, we know their earnings will be higher than $50 for each of them – as was our intention.

Gibbs explained that BBH will send the money directly to Front Steps, which will then cut money orders for each individual, while encouraging them to save some of it towards a possible security deposit or first month’s rent in permanent housing. The program ended every day at four in the afternoon because that’s when people start to line up for a place to sleep at Front Steps, which has one hundred beds and 115 sleeping mats, but still turns away close to fifty men per night.

But, according to Gibbs, it turns out that the money was not nearly as important as the experience–what everybody kept calling the “engagement.”

“The things that they kept talking about when they got back in [to the shelter] were, ‘somebody wanted to know about my childhood, (or) where I spent the night,'” he said.

On Monday, Gibbs briefed all the participants about the increased media attention they were going to receive while out.

“Don’t worry about us today,” one of the “Hotspots’ participants told him. “We’re gonna be fine.

“This has worked out a whole lot better than we thought it was going to, because these are the same people that would have walked right past me and not given me a second look,” he continued. “But because i’m wearing the t-shirt and because I’m participating in the program, it’s my opportunity to tell my story.”

A good deal of the criticism also focused on what the program wasn’t, rather than what it was. BBH said they got the idea for Homeless Hotspots from street newspapers, which are not only vended by homeless people, but partially produced by them. By comparison, merely providing Internet access doesn’t give the workers any creativity or sense of ownership.

And as a temporary program, the Hotspots were neither a true job nor a true entrepeneurial opportunity. As Sarah Jaffe of Alternet wrote, “when you actually own your own business, no one takes away your supplies after four days. You don’t work for a suggested donation. You work for a salary, for an hourly rate, when you work for a company.”

But both of these critiques act is if the choice was, “Homeless Hotspots” or something better, when in the real world it was merely “Homeless Hotspots,” or nothing. In fact, Gibbs said many homeless are already out there working temp jobs during SXSW–setting up and breaking down stages, or barking outside clubs. And as KXAN, NBC’s affiliate in Austin, reported, homeless people are also out during SXSW selling Blue Bell Ice Cream, a program run by Mobile Loaves and Fishes. Each treat is $1, and the vendors keep all proceeds (Blue Bell also donated the ice cream). It’s just a lot easier to be cynical about Internet marketing than ice cream.

Of course, the “Street Treats” vendors don’t have to wear a t-shirt that says “I am an ice cream sandwich.” As Erin Kissane tweeted, “the difference between ‘I’m running a hotspot’ and ‘I am a hotspot’ is a difference that matters.”

But the truth is that without the brazen–and potent, given that at SXSW, the whole world lives online, and the homeless want to get back in the world–metaphor, it’s not as good a marketing campaign.

Jenna Wortham’s New York Times story on the controversy unintentionally highlighted one final irony. It ends with this paragraph:

Adam Hanft, chief executive of the marketing advisory firm Hanft Projects, said that even if the effort was well intended, it seemed to turn a blind eye to that disconnect. “There is already a sense that the Internet community has become so absurdly self-involved that they don’t think there’s any world outside of theirs,” he said.

Except the Internet community was also so absurdly self-involved that they decided they knew better than the actual homeless people–that because the homeless belong to a vulnerable population, they were unable to make their own decision about participating in the program, and were not empowered enough (or smart enough) to see that the program should have been better, the way they, the Internet community, so clearly recognized.

In this video taken by Colorlines, Clarence, the most gregarious participant, talks about the program.

“If they’re talking about ‘what I’m going through,'” he says, “they need to come right here in front of the convention center where I stand, and plug in … let me get some of these lights lit up:”

That the controversy also came shortly after the death of Austin’s most famous homeless person, Leslie Cochran, also seemed sadly fitting. Some people in the city felt that Leslie’s place as Austin’s mascot was exploitive, trivializing, or insensitive, while others felt he was a great ambassador. Gibbs falls in the latter camp; as with the hotspots program, he is most in favor of awareness and visibility:

I look around at the way some other communities deal with their homeless populations and the thing that I can be very proud about–and it doesn’t always make everyone happy–is that they are very visible. They are still in front of us reminding us every day that our community can do more, and we must do more. We must build more affordable housing, we’ve got to give people more opportunies to get off the street and out of shelter. Whereas if you built a shelter ten miles from downtown, your community loses the perspective that we still have a problem.

And as I heard of Leslie’s death, I thought, this is the person that personifed this. Leslie never let us forget that our community has an issue of homelessness, and our community needed to step up to the plate and deal with homelessness.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- SXSW

- Homelessness